2013–2014 Zika virus outbreaks in Oceania

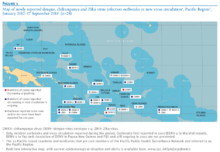

In October 2013, there was an outbreak of Zika fever in French Polynesia, the first outbreak of several Zika outbreaks across Oceania.[1] With 8,723 cases reported, it was the largest outbreak of Zika fever before the outbreak in the Americas that began in April 2015.[2] An earlier outbreak occurred on Yap Island in the Federated States of Micronesia in 2007, but it is thought that the 2013–2014 outbreak involved an independent introduction of the Zika virus from Southeast Asia.[3] Investigators suggested that the outbreaks of mosquito-borne diseases in the Pacific from 2012 to 2014 were "the early stages of a wave that will continue for several years",[1] particularly because of their vulnerability to infectious diseases stemming from isolation and immunologically naive populations.[1]

Epidemiology

French Polynesia

The first Zika outbreak started in French Polynesia in October 2013, with cases reported in the Society, Marquesas and Tuamotu Islands on Tahiti, Mo'orea, Raiatea, Tahaa, Bora Bora, Nuku Hiva and Arutua.[5][6] The outbreak ran concurrently with an outbreak of dengue fever.[1][7]

In December 2013, an American traveler to Mo'orea was diagnosed with Zika virus infection in New York after an 11-day history of symptoms,[8] becoming the first American tourist to be diagnosed with Zika.[9] A Japanese tourist returning to Japan was also diagnosed with Zika virus infection by the National Institute of Infectious Diseases after visiting Bora Bora, becoming the first imported case of Zika fever in Japan.[10]

By February 2014, it was estimated that more than 29,000 people with Zika-like symptoms had sought medical care, roughly 11.5% of the population,[11] with 8,503 suspected cases.[7] Of 746 samples tested at the Institut Louis-Malardé in Tahiti by 7 February, 396 (53.1%) were confirmed as containing the Zika virus by RT-PCR. Two further cases of Zika virus infection were imported into Japan,[12] and on 25 February, the Norwegian Institute of Public Health reported that a traveler returning to Norway from Tahiti was confirmed to have a Zika virus infection.[7]

By March 2014, the outbreak was declining in the majority of the islands,[7] and by October the outbreak had abated. A total of 8,723 suspected cases of Zika virus infection were reported, as well as more than 30,000 estimated clinical visits and medical consultations due to concerns about Zika.[1] The true number of Zika cases was estimated at more than 30,000.[5]

New Caledonia

Zika spread westwards from French Polynesia to New Caledonia, where imported cases from French Polynesia were reported from November 2013 onwards. The first indigenous case was confirmed in January 2014 by the Pasteur Institute.[1][13] On 10 February, there were 64 reported cases of Zika in the communities of Greater Nouméa, Dumbéa, and Ouvéa, of which 30 were imported from French Polynesia. By 26 February 2014, there were 140 confirmed cases of Zika in New Caledonia, including 32 imported cases.[7] The outbreak peaked in April, and by 17 September, the number of confirmed cases had gone up to 1,400, of which 35 were imported. During the same time period, there were also outbreaks of chikungunya fever and dengue fever.[1]

Cook Islands

In February 2014, an outbreak of Zika was reported in the Cook Islands, to the southwest of French Polynesia.[1] In March, an Australian woman was diagnosed with a Zika virus infection by Queensland Health following a recent trip to the Cook Islands, becoming the second reported case of Zika diagnosed in Australia.[14] Nearly 40 other cases of Zika virus infection were imported into New Zealand.[15] By 29 May, the outbreak had ended, with 50 confirmed and 932 suspected cases of Zika virus infection.[1]

Easter Island

By March 2014, there were one confirmed and 40 suspected cases of Zika virus infection on Easter Island. The Zika virus was suspected to have been carried to the island by a tourist from French Polynesia during the annual Tapati festival, held between January and February.[2] Chilean health authorities decided against issuing a health alert, saying that the outbreak had been contained and was under control, and advised travelers to take precautions against mosquito bites.[16] By the end of the year, 173 cases of Zika had been reported, but all of the cases were described as "mild".[17]

On 24 September 2014, a Belgian woman flying to Easter Island from Tahiti was diagnosed with Zika virus infection after having previously received ambulatory care in Tahiti, and was taken to Hanga Roa Hospital for evaluation. LAN Airlines undertook operations to ensure other people on the woman's flight were not infected, and local health authorities stated that Zika was not a risk for people on the island.[18]

Transmission

Zika is a mosquito-borne disease. Four aedine species of mosquito are found in the Pacific, including Aedes aegypti, widespread across the South Pacific, and Aedes polynesiensis, found between Fiji and French Polynesia. Aedes aegypti has previous been identified as a wild vector of the Zika virus, and preliminary results from the Institut Louis-Malardé have supported the main role of Aedes aegypti and probable role of Aedes polynesiensis in spreading the Zika virus.[12]

People infected with the Zika virus traveling to other Pacific islands could transmit the disease to local mosquitoes that bit them. The infected mosquitoes could then go on to spread Zika among the local mosquito population, and thence cause outbreaks of Zika among local people.[19][20]

A study conducted between November 2013 and February 2014 in French Polynesia found that 2.8% of blood donors tested positive for the Zika virus, of which 3% were asymptomatic at the time of blood donation. 11 of the infected donors studied subsequently reported symptoms of Zika virus infection within 10 days.[11] This indicated a potential risk of transmission of the Zika virus through blood transfusions, but there are no confirmed cases of this occurring.[21] Nucleic acid testing of blood donors was implemented in French Polynesia from 13 January 2014 onwards to prevent unintended transmission of the Zika virus.[11]

Possible links to neurological syndromes, infant microcephaly and other disorders

A concurrent increase in neurological syndromes and autoimmune complications was first reported in early 2014.[1][7] Of the 8,723 cases of Zika reported in French Polynesia, complications related to neurological signs of infection were noted in 74 people, including Guillain–Barré syndrome (GBS) in 42 people, as well as encephalitis, meningoencephalitis, paraesthesia, facial paralysis or myelitis in 25.[22] However, there was only one laboratory confirmation of Zika virus infection using RT-PCR in patients with GBS. Among the initial 38 cases of GBS found in suspected Zika cases, 73% were male and infected individuals were aged between 27 and 70. This was highly unusual, as prior to the Zika outbreak there had only been 21 cases of GBS in French Polynesia between 2009 and 2012. 18 people newly diagnosed with GBS were admitted to the local rehabilitation centre, putting heavy strain on the limited intensive care resources available.[12]

On 24 November 2015, health authorities in French Polynesia reported that there had been an unusual increase in the number of cases of central nervous system malformations in fetuses and infants during 2014–2015, coinciding with the outbreak of Zika on the islands. These malformations included 12 with fetal cerebral malformations or polymalformative syndromes, which includes microcephaly,[23] and another 5 with brainstem dysfunction and absence of swallowing, much greater than the annual average of one case. None of the pregnant women involved had medical signs of Zika virus infection, but four who were tested gave positive results in IgG serology assays for flaviviruses, suggesting an asymptomatic Zika virus infection during pregnancy. French Polynesian health authorities hypothesise that these abnormalities are associated with Zika if pregnant women are infected during the first or second trimester of pregnancy.[22] Dr. Didier Musso, an infectious disease specialist at the Institut Louis-Malardé, said that there was "very high suspicion" of a link between microcephaly and the Zika virus outbreak in French Polynesia, but added that further research was still needed.[23]

The two cases of Zika virus infection imported into Japan from French Polynesia in February 2014 showed signs of leukopenia (decreased levels of white blood cells) and moderate thrombocytopenia (decreased levels of platelets).[12]

Aftermath

Brazilian researchers have suggested that a traveler infected with the Zika virus arrived in Brazil from French Polynesia, leading to the ongoing Zika virus outbreak that began in 2015. This may have occurred during the 2014 FIFA World Cup tournament,[24] or shortly after, based on phylogenetic DNA analysis of the virus. French researchers have speculated that the virus arrived in August 2014, when canoeing teams from French Polynesia, New Caledonia, the Cook Islands and Easter Island attended the Va'a World Sprint Championships in Rio de Janeiro.[2][25][26]

Between 1 January and 20 May 2015, a further 82 confirmed cases of Zika were reported in New Caledonia, including ten imported cases.[21]

In early 2015, two cases of Zika virus infection were reported in travelers returning to Italy from French Polynesia.[5]

In February 2015, an outbreak of Zika began in the Solomon Islands. The Ministry of Health and Medical Services reported the first laboratory confirmation of Zika virus infection on 12 March 2015, and by 3 May 302 cases of Zika had been reported, with the number of new cases steadily decreasing.[21]

On 27 April 2015, the Ministry of Health of Vanuatu announced that blood samples collected prior to Cyclone Pam in March were confirmed to contain the Zika virus. The Ministry of Health advised people to consult medical aid if they experienced a high fever with no obvious cause, and recommended communities clean up places where mosquitoes could lay eggs.[27] The introduction of the Zika virus was thought to be linked to frequent travel between New Caledonia and Vanuatu.[2]

Local transmission of the Zika virus by mosquitoes has been reported in the Polynesian islands of American Samoa, Samoa, and Tonga since November 2015.[28] Cases of Zika virus infection have subsequently been confirmed in American Samoa,[29] Samoa,[30] Tonga,[31] and the Marshall Islands.[32]

See also

- 2015–16 Zika virus epidemic

- 2011–15 chikungunya outbreaks in Oceania

- Zika virus outbreak timeline

References

- Roth, Adam; Mercier, A; Lepers, C; Hoy, D; Duituturaga, S; Benyon, E; Guillaumot, L; Souarès, Y (16 October 2014). "Concurrent outbreaks of dengue, chikungunya and Zika virus infections – an unprecedented epidemic wave of mosquito-borne viruses in the Pacific 2012–2014". Eurosurveillance. 19 (41): 20929. doi:10.2807/1560-7917.ES2014.19.41.20929. PMID 25345518.

- Musso, Didier (October 2015). "Zika Virus Transmission from French Polynesia to Brazil". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 21 (10): 1887. doi:10.3201/eid2110.151125. PMC 4593458. PMID 26403318.

- Gatherer, Derek; Kohl, Alain (18 December 2015). "Zika virus: a previously slow pandemic spreads rapidly through the Americas" (PDF). Journal of General Virology. 97 (2): 269–73. doi:10.1099/jgv.0.000381. PMID 26684466.

- Roth, A; Mercier, A; Lepers, C; Hoy, D; Duituturaga, S; Benyon, E; Guillaumot, L; Souares, Y (16 October 2014). "Concurrent outbreaks of dengue, chikungunya and Zika virus infections - an unprecedented epidemic wave of mosquito-borne viruses in the Pacific 2012-2014". Eurosurveillance. 19 (41): 20929. doi:10.2807/1560-7917.ES2014.19.41.20929. PMID 25345518.

- Berger, Stephen (3 February 2015). Chikungunya and Zika: Global Status (2015 ed.). GIDEON Informatics, Inc. p. 75. ISBN 9781498806978. Retrieved 4 February 2016.

- Mallet, Dr. Henri-Pierre (27 October 2013). "ZIKA VIRUS - FRENCH POLYNESIA". ProMED-mail. Papeete: International Society for Infectious Diseases. Retrieved 7 February 2016.

- "Communicable Disease Threats Report" (PDF). Stockholm: European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. 1 March 2014. p. 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 January 2016. Retrieved 7 February 2016.

- Summers, Dr. Dyan J.; Acosta, Dr. Rebecca Wolfe; Acosta, Dr. Alberto M. (21 May 2015). "Zika Virus in an American Recreational Traveler". Journal of Travel Medicine. 22 (5): 338–340. doi:10.1111/jtm.12208. PMID 25996909.

- Maron, Dina Fine (8 October 2015). "Zika Disease: Another Reason to Hate Mosquitoes". Scientific American. Washington, D.C.: Macmillan Publishers. Retrieved 21 February 2016.

- Kutsuna, Dr. Satoshi (18 December 2013). "ZIKA VIRUS - JAPAN: ex FRENCH POLYNESIA". ProMED-mail. Toyama: International Society for Infectious Diseases. Retrieved 7 February 2016.

- Musso, D; Nhan, T; Robin, E; Roche, C; Bierlaire, D; Zisou, K; Shan Yan, A; Cao-Lormeau, VM; Broult, J (10 April 2014). "Potential for Zika virus transmission through blood transfusion demonstrated during an outbreak in French Polynesia, November 2013 to February 2014". Eurosurveillance. 19 (14): 20761. doi:10.2807/1560-7917.es2014.19.14.20761. PMID 24739982.

- "Zika virus infection outbreak, French Polynesia" (PDF). Stockholm: European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. 14 February 2014. pp. 2–4, 6, 8. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 March 2016. Retrieved 10 February 2016.

- "ZIKA VIRUS - PACIFIC (03): NEW CALEDONIA". ProMED-mail. International Society for Infectious Diseases. 22 January 2014. Retrieved 7 February 2016.

- Pyke, AT; Daly, MT; Cameron, JN; Moore, PR; Taylor, CT; Hewitson, GR; Humphreys, JL; Gair, R (2 June 2014). "Imported Zika Virus Infection from the Cook Islands into Australia, 2014". PLOS Currents: Outbreaks (1st ed.). 6. doi:10.1371/currents.outbreaks.4635a54dbffba2156fb2fd76dc49f65e. PMC 4055592. PMID 24944843. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

- "Dengue Fever, Zika and Chikungunya". Auckland Regional Public Health Service. 12 February 2016. Retrieved 12 February 2016.

- Schwan, Katharina (7 March 2014). "First Case of Zika Virus reported on Easter Island". The Disease Daily. HealthMap. Archived from the original on 1 March 2016. Retrieved 8 February 2016.

- Esposito, Anthony (3 February 2016). "Mainland Chile confirms first three cases of Zika virus". Santiago. Reuters. Retrieved 21 February 2016.

- "ZIKA VIRUS - PACIFIC (15): CHILE (EASTER ISLAND) ex TAHITI". ProMED-mail. International Society for Infectious Diseases. 24 September 2014. Retrieved 7 February 2016.

- "Where the mosquito-borne Zika virus is spreading". News.com.au. Reuters, News Corp Australia. 26 January 2016. Retrieved 12 February 2016.

Somebody would travel to say Brazil, get Zika virus there and come back to Cairns, or a South American traveller who’s visiting Australia is infected with Zika virus. If they’re bitten by the mosquitoes over here, the mosquitoes get infected and can potentially transmit the virus.

- Silver, Marc (5 February 2016). "Mapping Zika: From A Monkey In Uganda To A Growing Global Concern". NPR. Retrieved 12 February 2016.

It was suspected that mosquitoes had brought the disease to Yap Island. But Vasilakis says a previously infected human visitor could have been bitten by local mosquitoes, which then spread the virus.

- "Zika virus infection outbreak, Brazil and the Pacific region" (PDF). Stockholm: European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. 25 May 2015. pp. 4–5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 October 2015. Retrieved 12 February 2016.

- "Microcephaly in Brazil potentially linked to the Zika virus epidemic" (PDF). Stockholm: European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. 24 November 2015. pp. 4–5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 February 2016. Retrieved 8 February 2016.

- McNeil Jr., Donald G; Saint Louis, Catherine; St. Fleur, Nicholas (3 February 2016). "Short Answers to Hard Questions About Zika Virus". The New York Times. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

There is “very high suspicion” of a link between the Zika virus and microcephaly in French Polynesia, said Dr. Didier Musso, an infectious disease specialist at the archipelago’s Institut Louis Malardé – though he said additional research was still needed. Last November French Polynesian officials reinvestigated an outbreak of Zika that lasted from October 2013 to April 2014. They reported finding an unusual increase – from around one case annually to 17 cases in 2014-15 – of unborn babies developing “central nervous system malformations,” a classification that includes microcephaly.

- Romero, Simon (29 January 2016). "Tears and Bewilderment in Brazilian City Facing Zika Crisis". The New York Times. Retrieved 1 February 2016.

- McNeil, Jr., Donald G.; Romero, Simon; Tavernise, Sabrina (6 February 2016). "How a Medical Mystery in Brazil Led Doctors to Zika". The New York Times. Retrieved 7 February 2016.

- Murthy, Dr. Bhavini (28 January 2016). "Zika Virus Outbreak May Be Linked to Major Sporting Events". ABC News. Retrieved 1 February 2016.

- Willie, Glenda (27 April 2015). "Zika and dengue cases confirmed". Vanuatu Daily Post. Port Vila. Retrieved 12 February 2016.

- "Zika Virus in the Pacific Islands". Travelers' Health. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 5 February 2016. Retrieved 7 February 2016.

- Craig, Adam T; Butler, Michelle T; et al. (19 February 2016). "Update on Zika virus transmission in the Pacific islands, 2007 to February 2016 and failure of acute flaccid paralysis surveillance to signal Zika emergence in this setting". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 95 (1): 69–75. doi:10.2471/BLT.16.171892. PMC 5180343. PMID 28053366.

- Chang, Chris (26 January 2016). "Two pregnant Kiwi women cancel trips to Samoa after Zika outbreak". Television New Zealand. Retrieved 12 February 2016.

- "Tonga confirms 19 Zika cases". Radio New Zealand. 18 February 2016.

- "Communicable Disease Threats Report" (PDF). Stockholm: European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. 18 February 2016. p. 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 25 February 2016.