History of smallpox in Mexico

The history of smallpox in Mexico spans approximately 500 years from the arrival of the Spanish to the official eradication in 1951. It was brought to Mexico by those in Spanish ships, then spread to the center of Mexico, where it became a significant factor in the fall of Tenochtitlan. During the colonial period, there were major epidemic outbreaks which led to the implementation of sanitary and preventive policy. The introduction of smallpox inoculation in New Spain by Francisco Javier de Balmis and the work of Ignacio Bartolache reduced the mortality and morbidity of the disease.

Introduction of smallpox into Mexican History

Smallpox was an unknown disease not only in Mexico, but in all the Americas, before the arrival of Europeans. It was introduced to Mexican lands by the Spanish and played a significant role in the downfall of the Aztec Empire. Hernán Cortés departed from Cuba and arrived in Mexico in 1519, sent to start trade relations only on the Veracruz Coast. However, he disobeyed the Cuban governor and began to invade the mainland. The governor sent Pánfilo de Narváez after Cortés. Narvaez’s forces had at least one active case of smallpox, and when the Narvaez expedition stopped at Cozumel and Veracruz in 1520, the disease gained a foothold in the region.[1]

The introduction of smallpox among the Aztecs has been attributed to an African slave (by the name of Francisco Eguía, according to one account) but this has been disputed. From May to September, smallpox spread slowly to Tepeaca and Tlaxcala, and to Tenochtitlán by the fall of 1520. At this time, Cortes was returning to conquer the city after being thrown out on the Noche Triste.[2]

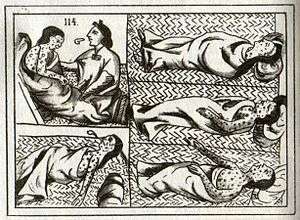

Cortes names only one indigenous leader who died of smallpox, Maxixcatzin. However, Cuitláhuac and other native rulers also died of smallpox. Chimalpahin reports the death of some lords in Chalco from the disease as well. These deaths were part of a widespread epidemic which decimated the common population. Estimates of mortality range from one-quarter to one-half of the population of central Mexico.[3] Toribio Motolinia, a Spanish monk that witnessed this epidemic, said: “It became such a great pestilence among them throughout the land that in most provinces more than half the population died; in others the proportion was less. They died in heaps, like bedbugs.”[1]

Major outbreak in the colonial period

During the colonial period, smallpox remained a scourge, especially on the indigenous population. There was a major epidemic between 1790 and 1791 that started in Valley of Mexico,[4] principally affecting children.[5] More people recovered than died. In Mexico City, of 5400 cases admitted to the hospital, 4431 recovered and 1,331 died. This epidemic coincided with the rise of prices of corn and a typhus epidemic, which caused a slight demographic decrease in central Mexico.[5]

Another smallpox epidemic came into Mexico from Guatemala in 1794. Oaxaca and Chiapas were the first places affected by smallpox because of proximity. The epidemic traveled from Oaxaca to Puebla, and then spread to Mexico City and Veracruz by 1797. By 1798, the epidemic had reached Saltillo and Zacatecas.[6] This outbreak is notable because that was the first time that sanitary and preventive campaigns were implemented in New Spain, such as quarantines, inoculation, isolation and the closing of roads.[5] Different institutions provided health and public services to fight against the smallpox epidemic: the most important were The “Ayuntamiento” or city council. The Catholic Church and "Real Tribunal del Protomedicato", which was an institution founded in 1630, managed all sanitary aspects of New Spain including the establishment of quarantines.[7] Charity boards were created, where rich people of the city donated money to build hospitals and to help and cure the sick. This charity board was led by the Spanish archbishop Alonso Núñez de Haro y Peralta.[6] The interest of rich people to help the poor was not purely philanthropic, as the death of those sectors caused economic problems because indigenous population was not able to pay tribute or work.[5]

The Church-managed hospitals and cemeteries forced people to bury dead people with lime at the outside of cities.[5] The isolation of sick people in hospitals or charities at the outsides of the cities was another important measure to stop the smallpox infection. These institutions took care of patients and provided them food and medicine. During the 1797 and 1798 outbreak, they also provided inoculation and were called inoculation houses. Although inoculation was practiced, the miasma theory of disease was still believed.[5]

In 1796, Gaceta de México published an article in which the use of inoculation was promoted, giving examples of kings and important persons who underwent the procedure.[8] In January 1798, the eradication of the 1790s epidemic was declared. The government proposed that the measures taken in that epidemic be implemented as the official policy in the case of a new epidemic, and it was approved by city council in April 1799. Viceroy Miguel José de Azanza, ordered an article written on 14 November 1799 about the benefits resulting from the inoculation in the 1790s epidemic and distributed to the population.[5]

In 1803, Spanish doctor Francisco Javier Balmis started a vaccination program against smallpox in New Spain, better known as Balmis Expedition, which reduced the severity and mortality in the epidemics that followed.[9] Before Balmis, Dr José María Arboleyda started a vaccination campaign in 1801 but this was not successful.[5]

There was another important outbreak in 1814 which started in Veracruz and extended to Mexico City, Tlaxcala and Hidalgo. This epidemic caused Viceroy Félix Calleja to take preventive measures like fumigations and vaccination, which were successful.[10]

There were sporadic outbreaks until 1826 when smallpox appeared in Yucatán, Tabasco and Veracruz brought by North American ships. In 1828, there were reported cases in Hidalgo, Oaxaca, State of Mexico, Guerrero, Chiapas, Chihuahua and Mexico City.[5][9]

Eradication

Efforts to eradicate smallpox in Mexico started when José Ignacio Bartolache wrote a book in 1779 about smallpox treatment called Instrucción que puede servir para que se cure a los enfermos de las viruelas epidemicas que ahora se padecen en México (Instructions that may help to cure smallpox in Mexico) in which he included an introduction describing the disease and instructions to treat it, such as drinking warm water with salt and honey, gargling with water and vinegar, keep tidy and clean and finish treatment by taking a purgative. He thought that smallpox was a remedy of nature to clear bad mood and doctors should not accelerate the process of healing because it was against nature.[11] He wrote a letter to propose his measures as a strategy to combat smallpox in which he also included recommendations like purify air with gunpowder and scent, ventilate churches where bodies were buried and to build cemeteries outside the city.[12] This strategy was approved by City Council in September 1779.[13]

The next phase of eradication started in 1803 when Francisco Javier de Balmis started a vaccination campaign in New Spain. This vaccine was used until 1951 when smallpox was declared officially eradicated in Mexico.[8] Military surgeon, Cristóval María Larrañaga, used this vaccine in the New Mexico province to inoculate thousands of people starting in 1804.

References

- Hays, J.N. (2006). Epidemics and Pandemicas. Santa Barbara, California: ABC CLIO. pp. 82–83. ISBN 1-85109-663-9.

- McCaa, Robert. "Spanish and Nahuatl Views on Smallpox and Demographic Catastrophe in the Conquest of Mexico". Archived from the original on 1995. Retrieved 7 May 2013.

- Alchon, Suzanne Austin (2003). A Pest in the Land. University of New Mexico Press.

- Gibson, Charles (1991). Los aztecas bajo el dominio español [Siglo XXI Editores México] (in Spanish) (1st ed.).

- Molina del Villar, América. "Contra una pandemia del Nuevo Mundo: las viruelas de las décadas de 1790 en México y las campañas de vacunación de Balmis y Salvany de 1803-1804 en los dominios coloniales" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 September 2008. Retrieved 23 April 2013.

- Hopkins, Donald (2002). The Greatest Killer:Smallpox in History. University of Chicago Press.

- Lozano, RM (1983). Memoria del III Congreso de Historia del Derecho Mexicano (in Spanish) (1st ed.).

- Franco-Paredes, Carlos (2004). "Perspectiva histórica de la viruela en México: aparición, eliminación y riesgo de reaparición por bioterrorismo". Gac. Méd. Méx: 321–327.

- Viesca, Carlos (2010). "Epidemias y enfermedades en tiempos de la Independencia". Revista Médica del Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social: 47–54.

- Calleja, Francisco (1814). Instrucción formada para administrar la vacuna (in Spanish). Imprenta de don Mariano Ontiveros.

- Bartolache, José Ignacio (1779). Instrucción que puede servir para que se cure a los enfermos de las viruelas epidemicas que ahora se padecen en México (in Spanish) (1st ed.). Impresa à instancia y expensas de dicha N. Ciudad.

- Molina del Villar, América. "Las prácticas sanitarias y médicas en la Ciudad de México, 1736-1739" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2001. Retrieved 23 April 2013.

- Zerón, H.M. (2005). "Dr. José Ignacio Bartolache. Semblanza". Ciencia Ergo Sum: 213–218.