Dengue fever

Dengue fever is a mosquito-borne tropical disease caused by the dengue virus.[1] Symptoms typically begin three to fourteen days after infection.[2] These may include a high fever, headache, vomiting, muscle and joint pains, and a characteristic skin rash.[1][2] Recovery generally takes two to seven days.[1] In a small proportion of cases, the disease develops into severe dengue, also known as dengue hemorrhagic fever, resulting in bleeding, low levels of blood platelets and blood plasma leakage, or into dengue shock syndrome, where dangerously low blood pressure occurs.[1][2]

| Dengue fever | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Dengue, breakbone fever[1][2] |

| The typical rash seen in dengue fever | |

| Pronunciation |

|

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

| Symptoms | Fever, headache, muscle and joint pain, rash[1][2] |

| Complications | Bleeding, low levels of blood platelets, dangerously low blood pressure[2] |

| Usual onset | 3–14 days after exposure[2] |

| Duration | 2–7 days[1] |

| Causes | Dengue virus by Aedes mosquitos[1] |

| Diagnostic method | Detecting antibodies to the virus or its RNA[2] |

| Differential diagnosis | Malaria, yellow fever, viral hepatitis, leptospirosis[3] |

| Prevention | Dengue fever vaccine, decreasing mosquito exposure[1][4] |

| Treatment | Supportive care, intravenous fluids, blood transfusions[2] |

| Frequency | 390 million per year[5] |

| Deaths | ~40,000[6] |

Dengue is spread by several species of female mosquitoes of the Aedes genus, principally Aedes aegypti.[1][2] The virus has five serotypes;[7][8] infection with one type usually gives lifelong immunity to that type, but only short-term immunity to the others.[1] Subsequent infection with a different type increases the risk of severe complications.[1] A number of tests are available to confirm the diagnosis including detecting antibodies to the virus or its RNA.[2]

A vaccine for dengue fever has been approved and is commercially available in a number of countries.[4][9] As of 2018, the vaccine is only recommended in individuals who have been previously infected, or in populations with a high rate of prior infection by age nine.[10][5] Other methods of prevention include reducing mosquito habitat and limiting exposure to bites.[1] This may be done by getting rid of or covering standing water and wearing clothing that covers much of the body.[1] Treatment of acute dengue is supportive and includes giving fluid either by mouth or intravenously for mild or moderate disease.[2] For more severe cases, blood transfusion may be required.[2] About half a million people require hospital admission every year.[1] Paracetamol (acetaminophen) is recommended instead of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) for fever reduction and pain relief in dengue due to an increased risk of bleeding from NSAID use.[2][11][12]

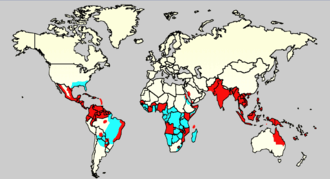

Dengue has become a global problem since the Second World War and is common in more than 120 countries, mainly in Southeast Asia, South Asia and South America.[5][13][14] About 390 million people are infected a year and approximately 40,000 die.[5][6] In 2019 a significant increase in the number of cases was seen.[15] The earliest descriptions of an outbreak date from 1779.[14] Its viral cause and spread were understood by the early 20th century.[16] Apart from eliminating the mosquitos, work is ongoing for medication targeted directly at the virus.[17] It is classified as a neglected tropical disease.[18]

Signs and symptoms

Typically, people infected with dengue virus are asymptomatic (80%) or have only mild symptoms such as an uncomplicated fever.[20][21][22] Others have more severe illness (5%), and in a small proportion it is life-threatening.[20][22] The incubation period (time between exposure and onset of symptoms) ranges from 3 to 14 days, but most often it is 4 to 7 days.[23] Therefore, travelers returning from endemic areas are unlikely to have dengue fever if symptoms start more than 14 days after arriving home.[13] Children often experience symptoms similar to those of the common cold and gastroenteritis (vomiting and diarrhea)[24] and have a greater risk of severe complications,[13][25] though initial symptoms are generally mild but include high fever.[25]

Clinical course

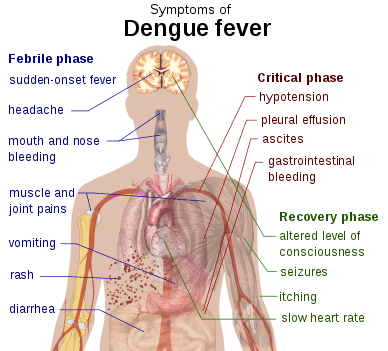

The characteristic symptoms of dengue are sudden-onset fever, headache (typically located behind the eyes), muscle and joint pains, and a rash. An alternative name for dengue, "breakbone fever", comes from the associated muscle and joint pains.[20][26] The course of infection is divided into three phases: febrile, critical, and recovery.[19]

The febrile phase involves high fever, potentially over 40 °C (104 °F), and is associated with generalized pain and a headache; this usually lasts two to seven days.[19][26] Nausea and vomiting may also occur.[25] A rash occurs in 50–80% of those with symptoms[26][27] in the first or second day of symptoms as flushed skin, or later in the course of illness (days 4–7), as a measles-like rash.[27][28] A rash described as "islands of white in a sea of red" has also been observed.[29] Some petechiae (small red spots that do not disappear when the skin is pressed, which are caused by broken capillaries) can appear at this point,[19] as may some mild bleeding from the mucous membranes of the mouth and nose.[13][26] The fever itself is classically biphasic or saddleback in nature, breaking and then returning for one or two days.[28][29]

In some people, the disease proceeds to a critical phase as fever resolves.[25] During this period, there is leakage of plasma from the blood vessels, typically lasting one to two days.[19] This may result in fluid accumulation in the chest and abdominal cavity as well as depletion of fluid from the circulation and decreased blood supply to vital organs.[19] There may also be organ dysfunction and severe bleeding, typically from the gastrointestinal tract.[13][19] Shock (dengue shock syndrome) and hemorrhage (dengue hemorrhagic fever) occur in less than 5% of all cases of dengue;[13] however, those who have previously been infected with other serotypes of dengue virus ("secondary infection") are at an increased risk.[13][30] This critical phase, while rare, occurs relatively more commonly in children and young adults.[25]

The recovery phase occurs next, with resorption of the leaked fluid into the bloodstream.[19] This usually lasts two to three days.[13] The improvement is often striking, and can be accompanied with severe itching and a slow heart rate.[13][19] Another rash may occur with either a maculopapular or a vasculitic appearance, which is followed by peeling of the skin.[25] During this stage, a fluid overload state may occur; if it affects the brain, it may cause a reduced level of consciousness or seizures.[13] A feeling of fatigue may last for weeks in adults.[25]

Associated problems

Dengue can occasionally affect several other body systems,[19] either in isolation or along with the classic dengue symptoms.[24] A decreased level of consciousness occurs in 0.5–6% of severe cases, which is attributable either to inflammation of the brain by the virus or indirectly as a result of impairment of vital organs, for example, the liver.[24][29][31]

Other neurological disorders have been reported in the context of dengue, such as transverse myelitis and Guillain–Barré syndrome.[24][31] Infection of the heart and acute liver failure are among the rarer complications.[13][19]

A pregnant woman who develops dengue is at higher risk of miscarriage, low birth weight birth, and premature birth.[32]

Cause

Virology

Dengue fever virus (DENV) is an RNA virus of the family Flaviviridae; genus Flavivirus. Other members of the same genus include yellow fever virus, West Nile virus, Zika virus, St. Louis encephalitis virus, Japanese encephalitis virus, tick-borne encephalitis virus, Kyasanur forest disease virus, and Omsk hemorrhagic fever virus.[29] Most are transmitted by arthropods (mosquitos or ticks), and are therefore also referred to as arboviruses (arthropod-borne viruses).[29]

The dengue virus genome (genetic material) contains about 11,000 nucleotide bases, which code for the three different types of protein molecules (C, prM and E) that form the virus particle and seven other non-structural protein molecules (NS1, NS2a, NS2b, NS3, NS4a, NS4b, NS5) that are found in infected host cells only and are required for replication of the virus.[30][33] There are five[7] strains of the virus, called serotypes, of which the first four are referred to as DENV-1, DENV-2, DENV-3 and DENV-4.[21] The fifth type was announced in 2013.[7] The distinctions between the serotypes are based on their antigenicity.[34]

Transmission

Dengue virus is primarily transmitted by Aedes mosquitos, particularly A. aegypti.[21] These mosquitos usually live between the latitudes of 35° North and 35° South below an elevation of 1,000 metres (3,300 ft).[21] They typically bite during the early morning and in the evening,[35][36] but they may bite and thus spread infection at any time of day.[37] Other Aedes species that transmit the disease include A. albopictus, A. polynesiensis and A. scutellaris.[21] Humans are the primary host of the virus,[21][29] but it also circulates in nonhuman primates.[38] An infection can be acquired via a single bite.[39] A female mosquito that takes a blood meal from a person infected with dengue fever, during the initial 2- to 10-day febrile period, becomes itself infected with the virus in the cells lining its gut.[40] About 8–10 days later, the virus spreads to other tissues including the mosquito's salivary glands and is subsequently released into its saliva. The virus seems to have no detrimental effect on the mosquito, which remains infected for life.[23] Aedes aegypti is particularly involved, as it prefers to lay its eggs in artificial water containers, to live in close proximity to humans, and to feed on people rather than other vertebrates.[23]

Dengue can also be transmitted via infected blood products and through organ donation.[41][42] In countries such as Singapore, where dengue is endemic, the risk is estimated to be between 1.6 and 6 per 10,000 transfusions.[43] Vertical transmission (from mother to child) during pregnancy or at birth has been reported.[44] Other person-to-person modes of transmission, including sexual transmission, have also been reported, but are very unusual.[26][45] The genetic variation in dengue viruses is region specific, suggestive that establishment into new territories is relatively infrequent, despite dengue emerging in new regions in recent decades.[25]

Predisposition

Severe disease is more common in babies and young children, and in contrast to many other infections, it is more common in children who are relatively well nourished.[13] Other risk factors for severe disease include female sex, high body mass index,[25] and viral load.[46] While each serotype can cause the full spectrum of disease,[30] virus strain is a risk factor.[25] Infection with one serotype is thought to produce lifelong immunity to that type, but only short-term protection against the other three.[21][26] The risk of severe disease from secondary infection increases if someone previously exposed to serotype DENV-1 contracts serotype DENV-2 or DENV-3, or if someone previously exposed to DENV-3 acquires DENV-2.[33] Dengue can be life-threatening in people with chronic diseases such as diabetes and asthma.[33]

Polymorphisms (normal variations) in particular genes have been linked with an increased risk of severe dengue complications. Examples include the genes coding for the proteins TNFα, mannan-binding lectin,[20] CTLA4, TGFβ,[30] DC-SIGN, PLCE1, and particular forms of human leukocyte antigen from gene variations of HLA-B.[25][33] A common genetic abnormality, especially in Africans, known as glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency, appears to increase the risk.[46] Polymorphisms in the genes for the vitamin D receptor and FcγR seem to offer protection against severe disease in secondary dengue infection.[33]

Mechanism

When a mosquito carrying dengue virus bites a person, the virus enters the skin together with the mosquito's saliva. It binds to and enters white blood cells, and reproduces inside the cells while they move throughout the body. The white blood cells respond by producing several signaling proteins, such as cytokines and interferons, which are responsible for many of the symptoms, such as the fever, the flu-like symptoms, and the severe pains. In severe infection, the virus production inside the body is greatly increased, and many more organs (such as the liver and the bone marrow) can be affected. Fluid from the bloodstream leaks through the wall of small blood vessels into body cavities due to capillary permeability. As a result, less blood circulates in the blood vessels, and the blood pressure becomes so low that it cannot supply sufficient blood to vital organs. Furthermore, dysfunction of the bone marrow due to infection of the stromal cells leads to reduced numbers of platelets, which are necessary for effective blood clotting; this increases the risk of bleeding, the other major complication of dengue fever.[46]

Viral replication

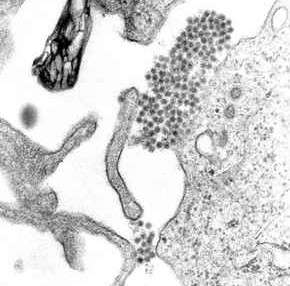

Once inside the skin, dengue virus binds to Langerhans cells (a population of dendritic cells in the skin that identifies pathogens).[46] The virus enters the cells through binding between viral proteins and membrane proteins on the Langerhans cell, specifically, the C-type lectins called DC-SIGN, mannose receptor and CLEC5A.[30] DC-SIGN, a non-specific receptor for foreign material on dendritic cells, seems to be the main point of entry.[33] The dendritic cell moves to the nearest lymph node. Meanwhile, the virus genome is translated in membrane-bound vesicles on the cell's endoplasmic reticulum, where the cell's protein synthesis apparatus produces new viral proteins that replicate the viral RNA and begin to form viral particles. Immature virus particles are transported to the Golgi apparatus, the part of the cell where some of the proteins receive necessary sugar chains (glycoproteins). The now mature new viruses are released by exocytosis. They are then able to enter other white blood cells, such as monocytes and macrophages.[30]

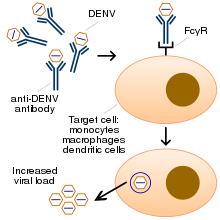

The initial reaction of infected cells is to produce interferon, a cytokine that raises many defenses against viral infection through the innate immune system by augmenting the production of a large group of proteins mediated by the JAK-STAT pathway. Some serotypes of the dengue virus appear to have mechanisms to slow down this process. Interferon also activates the adaptive immune system, which leads to the generation of antibodies against the virus as well as T cells that directly attack any cell infected with the virus.[30] Various antibodies are generated; some bind closely to the viral proteins and target them for phagocytosis (ingestion by specialized cells and destruction), but some bind the virus less well and appear instead to deliver the virus into a part of the phagocytes where it is not destroyed but can replicate further.[30]

Severe disease

It is not entirely clear why secondary infection with a different strain of dengue virus places people at risk of dengue hemorrhagic fever and dengue shock syndrome. The most widely accepted hypothesis is that of antibody-dependent enhancement (ADE). The exact mechanism behind ADE is unclear. It may be caused by poor binding of non-neutralizing antibodies and delivery into the wrong compartment of white blood cells that have ingested the virus for destruction.[30][33] There is a suspicion that ADE is not the only mechanism underlying severe dengue-related complications,[20][31] and various lines of research have implied a role for T cells and soluble factors such as cytokines and the complement system.[46]

Severe disease is marked by the problems of capillary permeability (an allowance of fluid and protein normally contained within the blood to pass) and disordered blood clotting.[24][25] These changes appear associated with a disordered state of the endothelial glycocalyx, which acts as a molecular filter of blood components.[25] Leaky capillaries (and the critical phase) are thought to be caused by an immune system response.[25] Other processes of interest include infected cells that become necrotic—which affect both coagulation and fibrinolysis (the opposing systems of blood clotting and clot degradation)—and low platelets in the blood, also a factor in normal clotting.[46]

Diagnosis

| Worsening abdominal pain | ||||

| Ongoing vomiting | ||||

| Liver enlargement | ||||

| Mucosal bleeding | ||||

| High hematocrit with low platelets | ||||

| Lethargy or restlessness | ||||

| Serosal effusions | ||||

The diagnosis of dengue is typically made clinically, on the basis of reported symptoms and physical examination; this applies especially in endemic areas.[20] However, early disease can be difficult to differentiate from other viral infections.[13] A probable diagnosis is based on the findings of fever plus two of the following: nausea and vomiting, rash, generalized pains, low white blood cell count, positive tourniquet test, or any warning sign (see table) in someone who lives in an endemic area.[47] Warning signs typically occur before the onset of severe dengue.[19] The tourniquet test, which is particularly useful in settings where no laboratory investigations are readily available, involves the application of a blood pressure cuff at between the diastolic and systolic pressure for five minutes, followed by the counting of any petechial hemorrhages; a higher number makes a diagnosis of dengue more likely with the cut off being more than 10 to 20 per 1 inch2 (6.25 cm2).[19][48]

The diagnosis should be considered in anyone who develops a fever within two weeks of being in the tropics or subtropics.[25] It can be difficult to distinguish dengue fever and chikungunya, a similar viral infection that shares many symptoms and occurs in similar parts of the world to dengue.[26] Often, investigations are performed to exclude other conditions that cause similar symptoms, such as malaria, leptospirosis, viral hemorrhagic fever, typhoid fever, meningococcal disease, measles, and influenza.[13][49] Zika fever also has similar symptoms as dengue.[50]

The earliest change detectable on laboratory investigations is a low white blood cell count, which may then be followed by low platelets and metabolic acidosis.[13] A moderately elevated level of aminotransferase (AST and ALT) from the liver is commonly associated with low platelets and white blood cells.[25] In severe disease, plasma leakage results in hemoconcentration (as indicated by a rising hematocrit) and hypoalbuminemia.[13] Pleural effusions or ascites can be detected by physical examination when large,[13] but the demonstration of fluid on ultrasound may assist in the early identification of dengue shock syndrome.[13][20] The use of ultrasound is limited by lack of availability in many settings.[20] Dengue shock syndrome is present if pulse pressure drops to ≤ 20 mm Hg along with peripheral vascular collapse.[25] Peripheral vascular collapse is determined in children via delayed capillary refill, rapid heart rate, or cold extremities.[19] While warning signs are an important aspect for early detection of potential serious disease, the evidence for any specific clinical or laboratory marker is weak.[51]

Classification

The World Health Organization's 2009 classification divides dengue fever into two groups: uncomplicated and severe.[20][47] This replaces the 1997 WHO classification, which needed to be simplified as it had been found to be too restrictive, though the older classification is still widely used[47] including by the World Health Organization's Regional Office for Southeast Asia as of 2011.[52] Severe dengue is defined as that associated with severe bleeding, severe organ dysfunction, or severe plasma leakage while all other cases are uncomplicated.[47] The 1997 classification divided dengue into an undifferentiated fever, dengue fever, and dengue hemorrhagic fever.[13][53] Dengue hemorrhagic fever was subdivided further into grades I–IV. Grade I is the presence only of easy bruising or a positive tourniquet test in someone with fever, grade II is the presence of spontaneous bleeding into the skin and elsewhere, grade III is the clinical evidence of shock, and grade IV is shock so severe that blood pressure and pulse cannot be detected.[53] Grades III and IV are referred to as "dengue shock syndrome".[47][53]

Laboratory tests

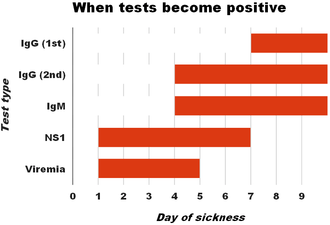

The diagnosis of dengue fever may be confirmed by microbiological laboratory testing.[47][54] This can be done by virus isolation in cell cultures, nucleic acid detection by PCR, viral antigen detection (such as for NS1) or specific antibodies (serology).[33][49] Virus isolation and nucleic acid detection are more accurate than antigen detection, but these tests are not widely available due to their greater cost.[49] Detection of NS1 during the febrile phase of a primary infection may be greater than 90% sensitive however is only 60–80% in subsequent infections.[25] All tests may be negative in the early stages of the disease.[13][33] PCR and viral antigen detection are more accurate in the first seven days.[25] In 2012 a PCR test was introduced that can run on equipment used to diagnose influenza; this is likely to improve access to PCR-based diagnosis.[55]

These laboratory tests are only of diagnostic value during the acute phase of the illness with the exception of serology. Tests for dengue virus-specific antibodies, types IgG and IgM, can be useful in confirming a diagnosis in the later stages of the infection. Both IgG and IgM are produced after 5–7 days. The highest levels (titres) of IgM are detected following a primary infection, but IgM is also produced in reinfection. IgM becomes undetectable 30–90 days after a primary infection, but earlier following re-infections. IgG, by contrast, remains detectable for over 60 years and, in the absence of symptoms, is a useful indicator of past infection. After a primary infection, IgG reaches peak levels in the blood after 14–21 days. In subsequent re-infections, levels peak earlier and the titres are usually higher. Both IgG and IgM provide protective immunity to the infecting serotype of the virus.[23][26][33] In testing for IgG and IgM antibodies there may be cross-reactivity with other flaviviruses which may result in a false positive after recent infections or vaccinations with yellow fever virus or Japanese encephalitis.[25] The detection of IgG alone is not considered diagnostic unless blood samples are collected 14 days apart and a greater than fourfold increase in levels of specific IgG is detected. In a person with symptoms, the detection of IgM is considered diagnostic.[23]

Prevention

Prevention depends on control of and protection from the bites of the mosquito that transmits it.[35][56] The World Health Organization recommends an Integrated Vector Control program consisting of five elements:[35]

- Advocacy, social mobilization and legislation to ensure that public health bodies and communities are strengthened;

- Collaboration between the health and other sectors (public and private);

- An integrated approach to disease control to maximize the use of resources;

- Evidence-based decision making to ensure any interventions are targeted appropriately; and

- Capacity-building to ensure an adequate response to the local situation.

The primary method of controlling A. aegypti is by eliminating its habitats.[35] This is done by getting rid of open sources of water, or if this is not possible, by adding insecticides or biological control agents to these areas.[35] Generalized spraying with organophosphate or pyrethroid insecticides, while sometimes done, is not thought to be effective.[22] Reducing open collections of water through environmental modification is the preferred method of control, given the concerns of negative health effects from insecticides and greater logistical difficulties with control agents.[35] People can prevent mosquito bites by wearing clothing that fully covers the skin, using mosquito netting while resting, and/or the application of insect repellent (DEET being the most effective).[39] While these measures can be an effective means of reducing an individual's risk of exposure, they do little in terms of mitigating the frequency of outbreaks, which appear to be on the rise in some areas, probably due to urbanization increasing the habitat of A. aegypti.[7] The range of the disease also appears to be expanding possibly due to climate change.[7]

Vaccine

In 2016 a partially effective vaccine for dengue fever became commercially available in the Philippines and Indonesia.[4][57] It has been approved for use by Mexico, Brazil, El Salvador, Costa Rica, Singapore, Paraguay, much of Europe, and the United States.[9][57][58] The vaccine is only recommended in individuals who have had a prior dengue infection or in populations where most (>80%) of people have been infected by age 9.[10][59] In those who have not had a prior infection there is evidence it may worsen subsequent infections.[9][10][5] For this reason Prescrire does not see it as suitable for wide scale immunization, even in areas were the disease is common.[60]

The vaccine is produced by Sanofi and goes by the brand name Dengvaxia.[61] It is based on a weakened combination of the yellow fever virus and each of the four dengue serotypes.[36][62] Studies of the vaccine found it was 66% effective and prevented more than 80 to 90% of severe cases.[59] This is less than wished for by some.[63] In Indonesia it costs about US$207 for the recommended three doses.[57]

Given the limitations of the current vaccine, research on vaccines continues, and the fifth serotype may be factored in.[7] One of the concerns is that a vaccine could increase the risk of severe disease through antibody-dependent enhancement (ADE).[64] The ideal vaccine is safe, effective after one or two injections, covers all serotypes, does not contribute to ADE, is easily transported and stored, and is both affordable and cost-effective.[64]

Anti-dengue day

International Anti-Dengue Day is observed every year on 15 June.[65] The idea was first agreed upon in 2010 with the first event held in Jakarta, Indonesia in 2011.[65] Further events were held in 2012 in Yangon, Myanmar and in 2013 in Vietnam.[65] Goals are to increase public awareness about dengue, mobilize resources for its prevention and control and, to demonstrate the Southeast Asian region's commitment in tackling the disease.[66]

Management

There are no specific antiviral drugs for dengue; however, maintaining proper fluid balance is important.[25] Treatment depends on the symptoms.[12] Those who can drink, are passing urine, have no "warning signs" and are otherwise healthy can be managed at home with daily follow-up and oral rehydration therapy.[12] Those who have other health problems, have "warning signs", or cannot manage regular follow-up should be cared for in hospital.[13][12] In those with severe dengue care should be provided in an area where there is access to an intensive care unit.[12]

Intravenous hydration, if required, is typically only needed for one or two days.[12] In children with shock due to dengue a rapid dose of 20 mL/kg is reasonable.[67] The rate of fluid administration is then titrated to a urinary output of 0.5–1 mL/kg/h, stable vital signs and normalization of hematocrit.[13] The smallest amount of fluid required to achieve this is recommended.[12]

Invasive medical procedures such as nasogastric intubation, intramuscular injections and arterial punctures are avoided, in view of the bleeding risk.[13] Paracetamol (acetaminophen) is used for fever and discomfort while NSAIDs such as ibuprofen and aspirin are avoided as they might aggravate the risk of bleeding.[12] Blood transfusion is initiated early in people presenting with unstable vital signs in the face of a decreasing hematocrit, rather than waiting for the hemoglobin concentration to decrease to some predetermined "transfusion trigger" level.[68] Packed red blood cells or whole blood are recommended, while platelets and fresh frozen plasma are usually not.[68] There is not enough evidence to determine if corticosteroids have a positive or negative effect in dengue fever.[69]

During the recovery phase intravenous fluids are discontinued to prevent a state of fluid overload.[13] If fluid overload occurs and vital signs are stable, stopping further fluid may be all that is needed.[68] If a person is outside of the critical phase, a loop diuretic such as furosemide may be used to eliminate excess fluid from the circulation.[68]

Prognosis

Most people with dengue recover without any ongoing problems.[47] The risk of death among those with severe dengue is 0.8% to 2.5%,[70] and with adequate treatment this is less than 1%.[47] However, those who develop significantly low blood pressure may have a fatality rate of up to 26%.[13] The risk of death among children less than five years old is four times greater than among those over the age of 10.[70] Elderly people are also at higher risk of a poor outcome.[70]

Epidemiology

Dengue is common in more than 120 countries.[5] In 2013 it caused about 60 million symptomatic infections worldwide, with 18% admitted to hospital and about 13,600 deaths.[71] The worldwide cost of dengue case is estimated US$9 billion.[71] For the decade of the 2000s, 12 countries in Southeast Asia were estimated to have about 3 million infections and 6,000 deaths annually.[72] In 2019 the Philippines declared a national dengue epidemic due to the deaths reaching 622 people that year.[73] It is reported in at least 22 countries in Africa; but is likely present in all of them with 20% of the population at risk.[74] This makes it one of the most common vector-borne diseases worldwide.[51]

Infections are most commonly acquired in the urban environment.[23] In recent decades, the expansion of villages, towns and cities in the areas in which it is common, and the increased mobility of people has increased the number of epidemics and circulating viruses. Dengue fever, which was once confined to Southeast Asia, has now spread to southern China in East Asia, countries in the Pacific Ocean and the Americas,[23] and might pose a threat to Europe.[22]

Rates of dengue increased 30 fold between 1960 and 2010.[75] This increase is believed to be due to a combination of urbanization, population growth, increased international travel, and global warming.[20] The geographical distribution is around the equator. Of the 2.5 billion people living in areas where it is common 70% are from the WHO Southeast Asia Region and Western Pacific Region.[75] An infection with dengue is second only to malaria as a diagnosed cause of fever among travelers returning from the developing world.[26] It is the most common viral disease transmitted by arthropods,[30] and has a disease burden estimated at 1,600 disability-adjusted life years per million population.[33] The World Health Organization counts dengue as one of seventeen neglected tropical diseases.[76]

Like most arboviruses, dengue virus is maintained in nature in cycles that involve preferred blood-sucking vectors and vertebrate hosts.[23] The viruses are maintained in the forests of Southeast Asia and Africa by transmission from female Aedes mosquitos—of species other than A. aegypti—to their offspring and to lower primates.[23] In towns and cities, the virus is primarily transmitted by the highly domesticated A. aegypti. In rural settings the virus is transmitted to humans by A. aegypti and other species of Aedes such as A. albopictus.[23] Both these species had expanding ranges in the second half of the 20th century.[25] In all settings the infected lower primates or humans greatly increase the number of circulating dengue viruses, in a process called amplification.[23] One projection estimates that climate change, urbanization, and other factors could result in more than 6 billion people at risk of dengue infection by 2080.[77]

History

The first record of a case of probable dengue fever is in a Chinese medical encyclopedia from the Jin Dynasty (265–420 AD) which referred to a "water poison" associated with flying insects.[14][78] The primary vector, A. aegypti, spread out of Africa in the 15th to 19th centuries due in part to increased globalization secondary to the slave trade.[25] There have been descriptions of epidemics in the 17th century, but the most plausible early reports of dengue epidemics are from 1779 and 1780, when an epidemic swept across Southeast Asia, Africa and North America.[14][79] From that time until 1940, epidemics were infrequent.[14]

In 1906, transmission by the Aedes mosquitos was confirmed, and in 1907 dengue was the second disease (after yellow fever) that was shown to be caused by a virus.[16] Further investigations by John Burton Cleland and Joseph Franklin Siler completed the basic understanding of dengue transmission.[16]

The marked spread of dengue during and after the Second World War has been attributed to ecologic disruption. The same trends also led to the spread of different serotypes of the disease to new areas and the emergence of dengue hemorrhagic fever. This severe form of the disease was first reported in the Philippines in 1953; by the 1970s, it had become a major cause of child mortality and had emerged in the Pacific and the Americas.[14] Dengue hemorrhagic fever and dengue shock syndrome were first noted in Central and South America in 1981, as DENV-2 was contracted by people who had previously been infected with DENV-1 several years earlier.[29]

Etymology

The origins of the Spanish word dengue are not certain, but it is possibly derived from dinga in the Swahili phrase Ka-dinga pepo, which describes the disease as being caused by an evil spirit.[78] Slaves in the West Indies having contracted dengue were said to have the posture and gait of a dandy, and the disease was known as "dandy fever".[80][81]

The term break-bone fever was applied by physician and United States Founding Father Benjamin Rush, in a 1789 report of the 1780 epidemic in Philadelphia. In the report title he uses the more formal term "bilious remitting fever".[82] The term dengue fever came into general use only after 1828.[81] Other historical terms include "breakheart fever" and "la dengue".[81] Terms for severe disease include "infectious thrombocytopenic purpura" and "Philippine", "Thai", or "Singapore hemorrhagic fever".[81]

Society and culture

Research

Research efforts to prevent and treat dengue include various means of vector control,[88] vaccine development, and antiviral drugs.[56]

Vector

With regards to vector control, a number of novel methods have been used to reduce mosquito numbers with some success including the placement of the guppy (Poecilia reticulata) or copepods in standing water to eat the mosquito larvae.[88] There are also trials with genetically modified male A. aegypti that after release into the wild mate with females, and render their offspring unable to fly.[89]

Wolbachia

Attempts are ongoing to infect the mosquito population with bacteria of the genus Wolbachia, which makes the mosquitos partially resistant to dengue virus.[25][90] While artificially induced infection with Wolbachia is effective, it is unclear if naturally acquired infections are protective.[91] Work is still ongoing as of 2015 to determine the best type of Wolbachia to use.[92]

Treatment

Apart from attempts to control the spread of the Aedes mosquito there are ongoing efforts to develop antiviral drugs that would be used to treat attacks of dengue fever and prevent severe complications.[17][93] Discovery of the structure of the viral proteins may aid the development of effective drugs.[17] There are several plausible targets. The first approach is inhibition of the viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (coded by NS5), which copies the viral genetic material, with nucleoside analogs. Secondly, it may be possible to develop specific inhibitors of the viral protease (coded by NS3), which splices viral proteins.[94] Finally, it may be possible to develop entry inhibitors, which stop the virus entering cells, or inhibitors of the 5′ capping process, which is required for viral replication.[93]

References

- "Dengue and severe dengue Fact sheet N°117". WHO. May 2015. Archived from the original on 2 September 2016. Retrieved 3 February 2016.

- Kularatne SA (September 2015). "Dengue fever". BMJ. 351: h4661. doi:10.1136/bmj.h4661. PMID 26374064.

- Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics: The field of pediatrics. Elsevier Health Sciences. 2016. p. 1631. ISBN 9781455775668. Archived from the original on 10 September 2017.

- East S (6 April 2016). "World's first dengue fever vaccine launched in the Philippines". CNN. Archived from the original on 18 October 2016. Retrieved 17 October 2016.

- "Dengue and severe dengue". www.who.int. Retrieved 29 February 2020.

- "Global, regional, and national age-sex-specific mortality for 282 causes of death in 195 countries and territories, 1980-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017". Lancet. 392 (10159): 1736–88. November 2018. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32203-7. PMC 6227606. PMID 30496103.

- Normile D (October 2013). "Tropical medicine. Surprising new dengue virus throws a spanner in disease control efforts". Science. 342 (6157): 415. doi:10.1126/science.342.6157.415. PMID 24159024.

- Mustafa MS, Rasotgi V, Jain S, Gupta V (January 2015). "Discovery of fifth serotype of dengue virus (DENV-5): A new public health dilemma in dengue control". Medical Journal, Armed Forces India. 71 (1): 67–70. doi:10.1016/j.mjafi.2014.09.011. PMC 4297835. PMID 25609867.

- "First FDA-approved vaccine for the prevention of dengue disease in endemic regions". FDA (Press release). 1 May 2019. Retrieved 4 May 2019.

- "Dengue vaccine: WHO position paper – September 2018" (PDF). Weekly Epidemiological Record. 36 (93): 457–76. 7 September 2018. Retrieved 12 April 2019.

- "Dengue". United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 28 March 2016. Retrieved 27 April 2018.

Use acetaminophen. Do not take pain relievers that contain aspirin and ibuprofen (Advil), it may lead to a greater tendency to bleed.

- WHO (2009), pp. 32–37.

- Ranjit S, Kissoon N (January 2011). "Dengue hemorrhagic fever and shock syndromes". Pediatric Critical Care Medicine. 12 (1): 90–100. doi:10.1097/PCC.0b013e3181e911a7. PMID 20639791.

- Gubler DJ (July 1998). "Dengue and dengue hemorrhagic fever". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 11 (3): 480–96. doi:10.1128/cmr.11.3.480. PMC 88892. PMID 9665979.

- "Dengue and severe dengue". www.who.int. Retrieved 15 December 2019.

- Henchal EA, Putnak JR (October 1990). "The dengue viruses". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 3 (4): 376–96. doi:10.1128/CMR.3.4.376. PMC 358169. PMID 2224837. Archived from the original on 25 July 2011.

- Noble CG, Chen YL, Dong H, Gu F, Lim SP, Schul W, Wang QY, Shi PY (March 2010). "Strategies for development of Dengue virus inhibitors". Antiviral Research. 85 (3): 450–62. doi:10.1016/j.antiviral.2009.12.011. PMID 20060421.

- "Neglected Tropical Diseases". cdc.gov. 6 June 2011. Archived from the original on 4 December 2014. Retrieved 28 November 2014.

- WHO (2009), pp. 25–27.

- Whitehorn J, Farrar J (2010). "Dengue". British Medical Bulletin. 95: 161–73. doi:10.1093/bmb/ldq019. PMID 20616106.

- WHO (2009), pp. 14–16.

- Reiter P (March 2010). "Yellow fever and dengue: a threat to Europe?". Euro Surveillance. 15 (10): 19509. doi:10.2807/ese.15.10.19509-en (inactive 6 June 2020). PMID 20403310. Archived from the original on 7 July 2011.

- Gubler DJ (2010). "Dengue viruses". In Mahy BWJ; Van Regenmortel MHV (eds.). Desk Encyclopedia of Human and Medical Virology. Boston: Academic Press. pp. 372–82. ISBN 978-0-12-375147-8. Archived from the original on 9 June 2016.

- Varatharaj A (2010). "Encephalitis in the clinical spectrum of dengue infection". Neurology India. 58 (4): 585–91. doi:10.4103/0028-3886.68655. PMID 20739797.

- Simmons CP, Farrar JJ, Nguyen vV, Wills B (April 2012). "Dengue" (PDF). The New England Journal of Medicine. 366 (15): 1423–32. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1110265. hdl:11343/191104. PMID 22494122.

- Chen LH, Wilson ME (October 2010). "Dengue and chikungunya infections in travelers". Current Opinion in Infectious Diseases. 23 (5): 438–44. doi:10.1097/QCO.0b013e32833c1d16. PMID 20581669.

- Wolff K; Johnson RA, eds. (2009). "Viral infections of skin and mucosa". Fitzpatrick's color atlas and synopsis of clinical dermatology (6th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. pp. 810–12. ISBN 978-0-07-159975-7.

- Knoop KJ, Stack LB, Storrow A, Thurman RJ, eds. (2010). "Tropical medicine". Atlas of emergency medicine (3rd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Professional. pp. 658–59. ISBN 978-0-07-149618-6.

- Gould EA, Solomon T (February 2008). "Pathogenic flaviviruses". Lancet. 371 (9611): 500–9. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60238-X. PMID 18262042. S2CID 205949828.

- Rodenhuis-Zybert IA, Wilschut J, Smit JM (August 2010). "Dengue virus life cycle: viral and host factors modulating infectivity" (PDF). Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 67 (16): 2773–86. doi:10.1007/s00018-010-0357-z. PMID 20372965. S2CID 4232236.

- Carod-Artal FJ, Wichmann O, Farrar J, Gascón J (September 2013). "Neurological complications of dengue virus infection". The Lancet. Neurology. 12 (9): 906–19. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70150-9. PMID 23948177. S2CID 13948773.

- Paixão ES, Teixeira MG, Costa MN, Rodrigues LC (July 2016). "Dengue during pregnancy and adverse fetal outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis". The Lancet. Infectious Diseases. 16 (7): 857–65. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(16)00088-8. PMID 26949028.

- Guzman MG, Halstead SB, Artsob H, Buchy P, Farrar J, Gubler DJ, Hunsperger E, Kroeger A, Margolis HS, Martínez E, Nathan MB, Pelegrino JL, Simmons C, Yoksan S, Peeling RW (December 2010). "Dengue: a continuing global threat". Nature Reviews. Microbiology. 8 (12 Suppl): S7–16. doi:10.1038/nrmicro2460. PMC 4333201. PMID 21079655.

- Solomonides T (2010). Healthgrid applications and core technologies : proceedings of HealthGrid 2010 ([Online-Ausg.] ed.). Amsterdam: IOS Press. p. 235. ISBN 978-1-60750-582-2. Archived from the original on 1 May 2016.

- WHO (2009), pp. 59–64.

- Global Strategy For Dengue Prevention And Control (PDF). World Health Organization. 2012. pp. 16–17. ISBN 978-92-4-150403-4. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 October 2012.

- "Travelers' Health Outbreak Notice". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2 June 2010. Archived from the original on 26 August 2010. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- "Vector-borne viral infections". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 3 February 2011. Retrieved 17 January 2011.

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. "Chapter 5 – dengue fever (DF) and dengue hemorrhagic fever (DHF)". 2010 Yellow Book. Archived from the original on 29 December 2010. Retrieved 23 December 2010.

- St. Georgiev, Vassil (2009). National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, NIH (1 ed.). Totowa, N.J.: Humana. p. 268. ISBN 978-1-60327-297-1. Archived from the original on 1 May 2016.

- Wilder-Smith A, Chen LH, Massad E, Wilson ME (January 2009). "Threat of dengue to blood safety in dengue-endemic countries". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 15 (1): 8–11. doi:10.3201/eid1501.071097. PMC 2660677. PMID 19116042.

- Stramer SL, Hollinger FB, Katz LM, Kleinman S, Metzel PS, Gregory KR, Dodd RY (August 2009). "Emerging infectious disease agents and their potential threat to transfusion safety". Transfusion. 49 (Suppl 2): 1S–29S. doi:10.1111/j.1537-2995.2009.02279.x. PMID 19686562.

- Teo D, Ng LC, Lam S (April 2009). "Is dengue a threat to the blood supply?". Transfusion Medicine. 19 (2): 66–77. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3148.2009.00916.x. PMC 2713854. PMID 19392949.

- Wiwanitkit V (November 2009). "Unusual mode of transmission of dengue". Journal of Infection in Developing Countries. 4 (1): 51–54. doi:10.3855/jidc.145. PMID 20130380.

- "News Scan for Nov 08, 2019". CIDRAP. Retrieved 12 November 2019.

- Martina BE, Koraka P, Osterhaus AD (October 2009). "Dengue virus pathogenesis: an integrated view". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 22 (4): 564–81. doi:10.1128/CMR.00035-09. PMC 2772360. PMID 19822889.

- WHO (2009), pp. 10–11.

- Halstead SB (2008). Dengue. London: Imperial College Press. p. 180 & 429. ISBN 978-1-84816-228-0. Archived from the original on 4 May 2016.

- WHO (2009), pp. 90–95.

- Musso D, Nilles EJ, Cao-Lormeau VM (October 2014). "Rapid spread of emerging Zika virus in the Pacific area". Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 20 (10): O595–96. doi:10.1111/1469-0691.12707. PMID 24909208.

- Yacoub S, Wills B (September 2014). "Predicting outcome from dengue". BMC Medicine. 12 (1): 147. doi:10.1186/s12916-014-0147-9. PMC 4154521. PMID 25259615.

- Comprehensive guidelines for prevention and control of dengue and dengue haemorrhagic fever (Rev. and expanded. ed.). New Delhi, India: World Health Organization Regional Office for South-East Asia. 2011. p. 17. ISBN 978-92-9022-387-0. Archived from the original on 14 June 2019. Retrieved 16 September 2017.

- WHO (1997). "Chapter 2: clinical diagnosis" (PDF). Dengue haemorrhagic fever: diagnosis, treatment, prevention and control (2nd ed.). Geneva: World Health Organization. pp. 12–23. ISBN 978-92-4-154500-6. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 October 2008.

- Wiwanitkit V (July 2010). "Dengue fever: diagnosis and treatment". Expert Review of Anti-Infective Therapy. 8 (7): 841–45. doi:10.1586/eri.10.53. PMID 20586568.

- "New CDC test for dengue approved". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 20 June 2012. Archived from the original on 31 August 2017.

- WHO (2009) p. 137–146.

- "Dengue Fever Vaccine Available in Indonesia". 17 October 2016. Archived from the original on 18 October 2016.

- "HSA Updates on Additional Risk of Dengvaxia® in Individuals with No Prior Dengue Experience". HSA Singapore. Archived from the original on 2 February 2018. Retrieved 2 February 2018.

- Torres JR, Falleiros-Arlant LH, Gessner BD, et al. (October 2019). "Updated recommendations of the International Dengue Initiative expert group for CYD-TDV vaccine implementation in Latin America". Vaccine. 37 (43): 6291–98. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.09.010. PMID 31515144.

- "Dengue vaccine (Dengvaxia°). Not for large-scale use". english.prescrire.org. 39 (433): 810. November 2019.

- "Dengvaxia®, World's First Dengue Vaccine, Approved in Mexico". www.sanofipasteur.com. Archived from the original on 10 December 2015. Retrieved 10 December 2015.

- Guy B, Barrere B, Malinowski C, Saville M, Teyssou R, Lang J (September 2011). "From research to phase III: preclinical, industrial and clinical development of the Sanofi Pasteur tetravalent dengue vaccine". Vaccine. 29 (42): 7229–41. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.06.094. PMID 21745521.

- Pollack, Andrew (9 December 2015). "First Dengue Fever Vaccine Approved by Mexico". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 9 December 2015. Retrieved 10 December 2015.

- Webster DP, Farrar J, Rowland-Jones S (November 2009). "Progress towards a dengue vaccine". The Lancet. Infectious Diseases. 9 (11): 678–87. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(09)70254-3. PMID 19850226.

- "Marking ASEAN Dengue Day". Archived from the original on 17 June 2015. Retrieved 16 June 2015.

- ACTION AGAINST DENGUE Dengue Day Campaigns Across Asia. World Health Organization. 2011. ISBN 9789290615392.

- de Caen AR, Berg MD, Chameides L, Gooden CK, Hickey RW, Scott HF, Sutton RM, Tijssen JA, Topjian A, van der Jagt ÉW, Schexnayder SM, Samson RA (November 2015). "Part 12: Pediatric Advanced Life Support: 2015 American Heart Association Guidelines Update for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care". Circulation. 132 (18 Suppl 2): S526–42. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000266. PMC 6191296. PMID 26473000.

- WHO (2009), pp. 40–43.

- Zhang F, Kramer CV (July 2014). "Corticosteroids for dengue infection". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 7 (7): CD003488. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003488.pub3. PMC 6555473. PMID 24984082.

- Kularatne SA (15 September 2015). "Dengue fever". BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.). 351: h4661. doi:10.1136/bmj.h4661. PMID 26374064.

- Shepard DS, Undurraga EA, Halasa YA, Stanaway JD (August 2016). "The global economic burden of dengue: a systematic analysis". The Lancet. Infectious Diseases. 16 (8): 935–41. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(16)00146-8. PMID 27091092.

- Shepard DS, Undurraga EA, Halasa YA (2013). Gubler DJ (ed.). "Economic and disease burden of dengue in Southeast Asia". PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 7 (2): e2055. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0002055. PMC 3578748. PMID 23437406.

- Ahmad K (March 2004). "Dengue death toll rises in Indonesia". The Lancet. 363 (9413): 956. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(04)15829-7. ISSN 0140-6736. PMID 15046118.

- Amarasinghe A, Kuritsk JN, Letson GW, Margolis HS (August 2011). "Dengue virus infection in Africa". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 17 (8): 1349–54. doi:10.3201/eid1708.101515. PMC 3381573. PMID 21801609.

- WHO (2009), p. 3.

- Neglected Tropical Diseases. "The 17 neglected tropical diseases". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 22 February 2014. Retrieved 10 April 2013.

- Messina JP, Brady OJ, Golding N, et al. (September 2019). "The current and future global distribution and population at risk of dengue". Nat Microbiol. 4 (9): 1508–15. doi:10.1038/s41564-019-0476-8. PMC 6784886. PMID 31182801.

- Anonymous (2006). "Etymologia: dengue" (PDF). Emerg. Infect. Dis. 12 (6): 893. doi:10.3201/eid1206.ET1206. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 December 2013.

- Kuno, Goro (12 November 2015). "A Re-Examination of the History of Etiologic Confusion between Dengue and Chikungunya". PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 9 (11). doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0004101.

1779–1780: “Knokkel-koorts” in Batavia (now Jakarta, Indonesia) and “break bone fever” in Philadelphia

- Anonymous (15 June 1998). "Definition of Dandy fever". MedicineNet.com. Archived from the original on 5 June 2011. Retrieved 25 December 2010.

- Halstead SB (2008). Dengue (Tropical Medicine: Science and Practice). River Edge, N.J: Imperial College Press. pp. 1–10. ISBN 978-1-84816-228-0. Archived from the original on 21 May 2016.

- Barrett AD, Stanberry LR (2009). Vaccines for biodefense and emerging and neglected diseases. San Diego: Academic. pp. 287–323. ISBN 978-0-12-369408-9. Archived from the original on 12 May 2016.

- Teo D, Ng LC, Lam S (April 2009). "Is dengue a threat to the blood supply?". Transfus Med. 19 (2): 66–77. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3148.2009.00916.x. PMC 2713854. PMID 19392949.

- "National Dengue Day". 6 June 2018. Retrieved 7 January 2019.

- "Calling for a World Dengue Day". The International Society for Neglected Tropical Diseases. Retrieved 7 January 2019.

- "Dengue Awareness Month | GOVPH". Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines. Official Gazette. 2 June 2011. Retrieved 7 January 2019.

- "Did you know: Dengue Awareness Month | Inquirer News". newsinfo.inquirer.net. 9 June 2015. Retrieved 7 January 2019.

- WHO (2009), p. 71.

- Fong, I (2013). Challenges in Infectious Diseases. Springer. p. 219. ISBN 978-1-4614-4496-1. Archived from the original on 17 June 2016.

- "'Bug' could combat dengue fever". BBC News. British Broadcasting Corporation. 2 January 2009. Archived from the original on 7 March 2009.

- Johnson KN (November 2015). "The Impact of Wolbachia on Virus Infection in Mosquitoes". Viruses. 7 (11): 5705–17. doi:10.3390/v7112903. PMC 4664976. PMID 26556361.

- Lambrechts L, Ferguson NM, Harris E, Holmes EC, McGraw EA, O'Neill SL, Ooi EE, Ritchie SA, Ryan PA, Scott TW, Simmons CP, Weaver SC (July 2015). "Assessing the epidemiological effect of wolbachia for dengue control". The Lancet. Infectious Diseases. 15 (7): 862–6. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00091-2. PMC 4824166. PMID 26051887.

- Sampath A, Padmanabhan R (January 2009). "Molecular targets for flavivirus drug discovery". Antiviral Research. 81 (1): 6–15. doi:10.1016/j.antiviral.2008.08.004. PMC 2647018. PMID 18796313.

- Tomlinson SM, Malmstrom RD, Watowich SJ (June 2009). "New approaches to structure-based discovery of dengue protease inhibitors". Infectious Disorders Drug Targets. 9 (3): 327–43. doi:10.2174/1871526510909030327. PMID 19519486. S2CID 28122851.

- WHO (2009). Dengue Guidelines for Diagnosis, Treatment, Prevention and Control (PDF). Geneva: World Health Organization. ISBN 978-92-4-154787-1.

External links

- Dengue fever at Curlie

- "Dengue". WHO. Retrieved 27 June 2011.

- "Dengue". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 27 June 2011.

- "DengueMap". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/HealthMap. Retrieved 27 June 2011.

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

.jpg)