2009 Bolivian dengue fever epidemic

The 2009 Bolivian dengue fever epidemic was an epidemic of dengue fever which struck Bolivia in early 2009, escalating into a national emergency by February. The BBC described it as the worst outbreak of dengue fever in the country's history. At least 18 people died and 31,000 were infected by the mosquito-transmitted arbovirus.

On 20 February, the Pan American Health Organization reported that eighty (80) cases of the more severe dengue hemorrhagic fever had occurred in Bolivia since January, of which 22% were fatal.[1] Bolivia requested outside assistance and foreign aid.

Background

Bolivia first declared a national emergency in early February 2009, when it alerted the world about the country's worst outbreak of dengue fever in twenty-two years.[2] By 3 February, five people had died in the east of the country and over 7,000 more were infected.[2] Worst hit is the Santa Cruz Department, near the Paraguayan border and the Amazon.[2] A number of military facilities, particularly in the city of Santa Cruz, were turned into temporary hospitals as the real hospitals struggled to cope with the conditions.[2] Thousands of soldiers were mobilized to assist medical workers.[2] The government then allocated funds to supply hospitals across the country; however, it was criticised in some quarters for the slowness of its actions.[1][2] The infection was most widespread in the tropical eastern lowlands, where conditions led to a thriving mosquito population.[1] Bolivia's healthcare services had difficulty in coping with the outbreak, with experts from Venezuela, Cuba, Paraguay and the World Health Organization called in to assist.[1]

Foreign aid

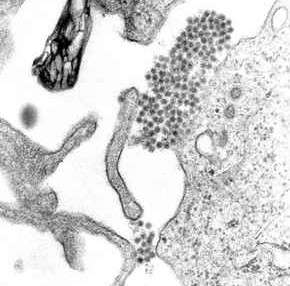

Mosquito transmission

Mosquitoes thrive in the high temperatures and humidity of the Bolivian lowlands and it was that region which saw the highest numbers of infected civilians.[1] There is currently no vaccine for dengue fever.[1] Those infected experience flu-like symptoms such as severe headaches, fevers and joint pain.[1] 1 of 4 people infected with dengue will develop symptoms.[3] There is no specific treatment for dengue, other than managing the symptoms. The best way to address dengue is to disrupt the mosquito's habitat. Mosquitos breed in stagnant water, i.e. open storage containers, discarded tires, and uncollected garbage.[4] The infected are advised by medical experts to drink plenty of fluids and obtain significant rest.[1] Dengue fever sufferers have an approximate 1% chance of progressing to the more severe dengue hemorrhagic fever.[1] 1 of 20 individuals who become ill with dengue will develop severe dengue. Severe dengue can lead to life threatening condition including shock, internal bleeding, or death.[3] Other symptoms include hypothermia, vomiting, severe abdominal pain and confusion. The global average case-fatality ratio for dengue hemorrhagic fever is 5%.[1]

See also

- 2009 West African meningitis outbreak

References

- "Dengue fever worsens in Bolivia". BBC. 2009-02-26. Archived from the original on 1 March 2009. Retrieved 2009-02-26.

- "Dengue fever outbreak in Bolivia". BBC. 2009-02-03. Archived from the original on 6 February 2009. Retrieved 2009-02-26.

- "Symptoms and Treatment | Dengue | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 2019-09-26. Retrieved 2019-10-18.

- Schmidt, Wolf-Peter; Suzuki, Motoi; Dinh Thiem, Vu; White, Richard G.; Tsuzuki, Ataru; Yoshida, Lay-Myint; Yanai, Hideki; Haque, Ubydul; Huu Tho, Le; Anh, Dang Duc; Ariyoshi, Koya (2011-08-30). "Population Density, Water Supply, and the Risk of Dengue Fever in Vietnam: Cohort Study and Spatial Analysis". PLoS Medicine. 8 (8): e1001082. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001082. ISSN 1549-1277. PMC 3168879. PMID 21918642.