2018 Équateur province Ebola outbreak

The 2018 Équateur province Ebola outbreak occurred in the north-west of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) from May to July 2018. It was contained entirely within Équateur province, and was the first time that vaccination with the rVSV-ZEBOV Ebola vaccine had been attempted in the early stages of an Ebola outbreak,[6] with a total of 3,481 people vaccinated.[7][8][9] It was the ninth recorded Ebola outbreak in the DRC.[7]

| Initial case: 8 May 2018[1][2] Declared over: 24 July 2018[3] | |

_-_%C3%89quateur.svg.png) Location of the Province of Équateur in the Democratic Republic of the Congo | |

.svg.png) Location of the Democratic Republic of the Congo in Africa | |

| Confirmed cases | 38[4] |

|---|---|

| Probable cases | 16[5] |

| Deaths | 33[5] |

The outbreak began on 8 May 2018, when it was reported that 17 people were suspected of having died from EVD near the town of Bikoro in the Province of Équateur.[10] The World Health Organization declared the outbreak after two people were confirmed as having the disease.[1][11] On 17 May, the virus was confirmed to have spread to the inland port city of Mbandaka, causing the WHO to raise its assessment of the national risk level to "very high",[12][13] but not yet to constitute an international public health emergency.[14] The WHO declared the outbreak over on 24 July 2018.[15][16][3]

Subsequent to the end of this outbreak, the Kivu Ebola epidemic commenced in the eastern region of the country on 1 August 2018,[17] and is still ongoing as of April 2020.[18] A further separate outbreak in the Province of Équateur was announced on 1 June 2020 by the Congolese health ministry, described as the eleventh Ebola outbreak since records began.[19]

Epidemiology

Early cases

|

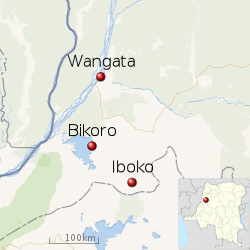

| Location of suspected cases reported |

The earliest cases are believed to have occurred in early April 2018.[6] The suspected index case was a police officer, who died in a health center in the village of Ikoko-Impenge, near the market town of Bikoro in Équateur province, according to the International Federation of the Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies.[20]

After his funeral, eleven family members became ill, and seven of them died. All of the seven deceased had attended the man's funeral or cared for him while he was sick.[20] The identification of this individual as the index case has not yet been confirmed.[21]

Équateur province's Provincial Health Division reported 21 cases with symptoms consistent with Ebola virus disease, of whom 17 had died, on 3 May 2018.[22] Of these, eight cases were subsequently shown not to have been Ebola-related.[23] The outbreak was declared on 8 May after samples from two of five patients in Bikoro tested positive for the Zaire strain of the Ebola virus.[1][22][10]

On 10 May, the World Health Organization (WHO) stated that the Democratic Republic of the Congo had a total of 32 cases of EVD,[2] and a further two suspected cases were announced on the following day, bringing the total cases to 34, all located in the Bikoro area of DRC.[24]

| Date | Cases | Deaths | CFR | Contacts | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Confirmed | Probable | Suspected | Total | ||||

| 2018-05-11[26] | 2 | 18 | 14 | 34 | 18 | 52.9% | 75 |

| 2018-05-14[27] | 2 | 22 | 17 | 41 | 20 | 48.8% | 432 |

| 2018-05-18[22] | 14 | 21 | 10 | 45 | 25 | 55.6% | 532 |

| 2018-05-20[21] | 28 | 21 | 2 | 51 | 27 | 52.9% | 628 |

| 2018-05-23[23] | 31 | 13 | 8 | 52 | 22* | 42.3% | >600[28] |

| 2018-05-27[29] | 35 | 13 | 6 | 54 | 25 | 46.3% | 906 |

| 2018-05-30[30] | 37 | 13 | 0 | 50* | 25 | 50% | >900[31] |

| 2018-06-03[32] | 37 | 13 | 6 | 56 | 25 | 44.6% | 880 |

| 2018-06-06[33] | 38 | 14 | 10 | 62 | 27 | 43.6% | 619 |

| 2018-06-10[34] | 38 | 14 | 3 | 55* | 28 | 50.9% | 634 |

| 2018-06-17[35] | 38 | 14 | 10 | 62 | 28 | 45.1% | 289 |

| 2018-06-20[15] | 38 | 14 | 9 | 61* | 28 | 45.9% | 179 |

| 2018-06-24[36] | 38 | 14 | 3 | 55* | 28 | 51% | 179 |

| 2018-06-29[37] | 38 | 15 | 0 | 53* | 29 | 54.7% | 0 |

| 2018-07-09[38] | 38 | 15 | 0 | 53 | 29 | 54.7% | 0 |

| 2018-07-24[7] | 38 | 16 | 0 | 54 | 33 | 61% | 0 |

|

* numbers are subject to revision both up, when new cases are discovered, and down, when tests show cases were not Ebola-related. | |||||||

Spread to Mbandaka

In the eight previous Ebola outbreaks in DRC since 1976, the virus had never before reached a major city. In May 2018, for the first time, four cases were confirmed in the city of Mbandaka.[39][23]

On 14 May, suspected cases were reported in the Iboko and Wangata areas in Équateur province, in addition to Bikoro. The WHO reported on 17 May 2018 that the first case of this outbreak in an urban area[20] had been confirmed in the Wangata district of Mbandaka city, the capital of Équateur province, about 100 miles north of Bikoro.[20][27][12] Mbandaka is a busy, densely populated port on the Congo River with a population of 1.2 million,[40] leading to a high risk of contagion.[22][20] The following day, the WHO raised the health risk in DRC to "very high" due to the presence of the virus in an urban area.[13]

The DRC government was particularly concerned about the virus spreading by boat transport along the Congo between Mbandaka and the capital, Kinshasa.[41] The WHO also considered that there was a high risk of the outbreak spreading to nine other countries in the region,[22] including the bordering Republic of the Congo and Central African Republic.[41][40]

As of 23 May 2018, the focus of the outbreak was split between Bikoro and Iboko; Iboko had 55% of the confirmed cases of EVD[23] and Bikoro had 81.5% of the fatalities.[21] The cases in the Bikoro health zone were located in Ikoko Impenge (12), Bikoro (6), Momboyo (1) and Moheli (1); those in the Iboko health zone were located in Itipo (13), Mpangi (2), Wenga (1) and Loongo (1).[23]

According to the fifth situation report released by the WHO, the case fatality rate (CFR) was 42.3%.[23] Demographics had been reported for 44 cases as of 22 May; there were 26 cases of EVD in men and 18 in women; 7 cases were in children 14 years and under, and 9 were in those over 60 years.[23] By 23 May, there had been 5 reported cases in health-care workers, including two who died.[23] Contact tracing was being employed to identify contacts with infected individuals.[21][42] On 29 May, it was reported that 800 contacts had been identified in the city of Mbandaka;[43] the next day it was reported that 500 people in the city had been vaccinated.[44]

| Health zone | Cases | Deaths | CFR | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Confirmed | Probable | Suspected | Total | |||

| Bikoro | 10 | 11 | 0 | 21 | 18 | 85.7% |

| Iboko | 24 | 5 | 0 | 29 | 12 | 41.3% |

| Wangata | 4 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 3 | 75% |

| Ingende[35] | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | - |

| Total | 38 | 16 | 0 | 54 | 33 | 61% |

On 29 May, the WHO indicated that nine neighbouring countries had been alerted for being at high risk of spread of EVD,[45] On 4 June, it was reported that Angola had closed its border with the DRC due to the outbreak.[46]

End of the outbreak

This outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo was declared over on 24 July 2018 after 42 days passed without any new confirmed cases.[47][16][39] Although it was noted that a new outbreak occurred only one week later in the eastern region of Kivu; and it has been established that they are not linked.[17]

Containment challenges

The Bikoro area had three hospitals, but the area's health services were described by WHO as predominantly having "limited functionality";[22] they received supplies from international bodies but experienced frequent shortages. More than half of the Bikoro area cases were in Ikoko-Impenge, a village not connected to the road system.[22][23] Bikoro lies in dense rain forest,[20] and the area's remoteness and inadequate infrastructure hindered treatment of EVD patients, as well as surveillance and vaccination efforts.[40]

Adherence was another challenge: on 20–21 May, three individuals with EVD in an isolation ward of a treatment center in Mbandaka fled; two later died after attending a prayer meeting, at which they may have exposed 50 other attendees to the virus.[48][49][50][51] Bushmeat was believed to be one vector of infection, but bushmeat vendors at the Mbandaka market told reporters that they did not believe Ebola was real or serious.[52] Hostility towards health workers trying to offer medical assistance was also reported.[53] On 29 May, the WHO forecast that there would be 100–300 cases by the end of July.[54]

Virology

Zaire ebolavirus, which was identified in this outbreak,[22] is included in genus Ebolavirus, family Filoviridae,[55]

The virus was named for the Ebola River, which runs as a tributary of the Congo River in the Democratic Republic of the Congo; the Zaire strain was first identified in 1976 in Yambuku.[56][57]

Response

Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) established treatment centers in Bikoro, Ikoko and Wangata.[23] WHO sent an expert team to Bikoro on 8 May,[1] and on 13 May, WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus visited the town.[58] On 18 May, the WHO IHR committee met and decided against declaring a Public Health Emergency of International Concern.[40] As of 24 May 2018, WHO had sent 138 technical personnel to the three affected areas; the Red Cross sent more than 150 people, and UNICEF personnel were also active.[23] Other international agencies sending teams included the UK Public Health Rapid Support Team[59] and the Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention.[60] The Wellcome Trust donated £2 million towards the DRC outbreak.[61] Merck donated its experimental vaccine and Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance helped to support vaccination operations.[62] Several tons of supplies were shipped to the DRC, including protection and disinfection kits and palliative drugs.[20] After the virus spread to the city of Mbandaka, DRC health minister Oly Ilunga Kalenga announced that healthcare would be provided free for those affected.[63][64]

US President Donald Trump has advocated rescinding Ebola funding and most financing for State Department emergency responses. National Security Advisor John Bolton removed the National Security Council’s health security chief on the day that the Ebola outbreak was declared, shutting down the entire epidemic prevention office.[65] The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says “about five” of its staff advise the Congolese government. CDC presence appears to be smaller than West African countries'. The U.S. Agency for International Development promised $1 million to WHO for Ebola efforts. Germany has promised $5.8 million.[65]

Surveillance

Surveillance of travelers at Mbandaka's port and airport was performed.[22] The DRC Ministry of Public Health identified 115 areas where movement of people increased the risk of virus transmission, including 83 river ports, nine airports and seven bus stations, as well as 16 markets.[21] José Makila, the DRC minister of transport, stated that the Navy would be used to surveil river traffic on the Congo.[41] On 10 May, the Nigerian Ministry of Health reported it would start screening at its borders,[66] and on 18 May 2018, a total of 20 countries had instituted screening of travelers coming from the DRC.[22] WHO sent teams to 8/9 of the neighboring countries to assess their capability to deal with EVD spread and facilitate their surveillance.[23] The DRC Ministry of Public Health worked with surveyors and cartographers from UCLA and OpenStreetMap DRC to improve mapping of the affected area.[67] A laboratory commenced operations in Bikoro on 16 May, enabling local testing of patient samples for Ebola virus.[21]

Burials were organized by MSF and the Red Cross of the Democratic Republic of the Congo to minimize the risk of transmission.[22] The United Nations Radio broadcast EVD awareness information, and posters and leaflets were prepared and distributed.[22] UNICEF warned 143 churches across Mbandaka of the risks of prayer meetings.[23]

Treatment

Ring vaccination with rVSV-ZEBOV

Health authorities including DRC's Ministry of Public Health used recombinant vesicular stomatitis virus–Zaire Ebola virus (rVSV-ZEBOV) vaccine – a recently developed experimental Ebola vaccine, produced by Merck – to try to suppress the outbreak. This live-attenuated vaccine expresses the surface glycoprotein of the Kikwit 1995 strain of Zaire ebolavirus in a recombinant vesicular stomatitis virus vector.[68] rVSV-ZEBOV was trialed in Guinea and Sierra Leone during the West African epidemic of 2013–16, with 5837 people receiving the vaccine; the trial authors concluded that rVSV-ZEBOV provided "substantial protection" against EVD,[69] but subsequent commentators have questioned the degree of protection obtained[70] and the degree of long-term protection conferred is unknown.[71] As the vaccine had not been approved by any regulatory authority, it was used in DRC under a compassionate use trial protocol.[6]

A ring vaccination strategy was used, which involves vaccinating only those most likely to be infected: direct contacts of infected individuals, and contacts of those contacts.[20][72][73][74][75] Other groups targeted included health workers, laboratory personnel, surveillance workers and people involved with burials.[62][76] People who were vaccinated were followed up for 84 days to assess whether they were protected from infection and to monitor any adverse events.[6] A total of 4,320 doses of the rVSV-ZEBOV vaccine were delivered to DRC's capital Kinshasa by WHO on 16 May, and a further 3,240 doses arrived three days later;[21] with another 8,000 doses to be made available.[77] The vaccine must be transported and stored at between −60 and −80 °C.[62] A cold chain was established in Kinshasa by 18 May and has been extended to Mbandaka. WHO planned to concentrate on vaccinating three sets of contacts of confirmed EVD cases, two in Bikoro and one in Mbandaka.[22]

Vaccination started on 21 May among health workers in Mbandaka,[64] with 7,560 vaccine doses ready for immediate use, according to WHO.[21][62] The DRC health minister Oly Ilunga Kalenga stated that vaccination of health workers and Ebola case contacts in the Wangata and Bolenge areas of Mbandaka would take five days, after which vaccination would start in Bikoro and Iboko.[64] As of 24 May 2018, 154 people in Mbandaka had been vaccinated, and preparations were started for vaccinating in Bikoro and Iboko.[23]

Up to 1,000 people were expected to have been vaccinated by 26 May, according to WHO.[21] It was the first time that vaccination had been attempted in the early stages of an Ebola outbreak.[6]

The rVSV-ZEBOV vaccine proved effective for the strain of the Ebola virus in this outbreak, having via ring vaccination protected some 3,481 individuals.[7]

Experimental therapeutic agents

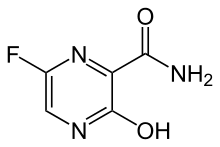

Health officials considered trialing experimental treatments, including the antiviral agents favipiravir and GS-5734, and the antibody ZMapp. All three agents were given to patients during the West African epidemic, but none has yet been proved to be effective.[78] The DRC Ministry of Public Health also requested that the US trial mAb114 treatment during the outbreak. The mAb114 monoclonal antibody was developed by the National Institutes of Health and Jean-Jacques Muyembe at the National Institute for Biomedical Research, and is derived from an EVD survivor of the 1995 Kikwit outbreak who still had circulating anti-Ebola antibodies eleven years later; it has been tested in macaques but not in humans.[51][79][80]

The ZMapp cocktail was assessed by the World Health Organization for emergency use under the MEURI ethical protocol. The panel agreed that "the benefits of ZMapp outweigh its risks" while noting that it presented logistical challenges, particularly that of requiring a cold chain for distribution and storage.[81] Despite being at earlier stages of development, three other therapies, mAb114, remdesivir and REGN3470-3471-3479, were also approved for emergency use under MEURI and the Ministry of Health in the DRC.[81][82]

Prognosis

Post-Ebola virus syndrome affects those who have survived EVD infection; the resulting signs and symptoms can include muscle pain, eye problems and neurological problems.[83]

History

The Democratic Republic of the Congo (formerly Zaire) has had several previous EVD outbreaks since 1976,[84][85] which are summarised in the Table below. All have been located in the west or north of the country.[77] Three previous outbreaks (in 1976, 1977 and 2014) occurring in former province of Équateur, of which the current Équateur province forms part.[2]

In 2014, the WHO considered that the DRC was lagging behind the rest of Africa in health expenditures, at the relative rate of Intl$32 per head.[86][87]

For the 2017 Democratic Republic of the Congo Ebola virus outbreak, the DRC regulatory authorities approved the use of the experimental rVSV-ZEBOV vaccine, but logistical issues delayed its implementation until the outbreak was already under control.[6][78][88]

Shortly before the first cases of the 2018 Ebola outbreak, the country experienced a widespread cholera epidemic (June 2017 – spring 2018), which was the most serious in the country since 1994.[89][90][91]

V・T Date | Country | Major location | Outbreak information | Source | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strain | Cases | Deaths | CFR | ||||

| Aug 1976 | Zaire | Yambuku | EBOV | 318 | 280 | 88% | [92] |

| Jun 1977 | Zaire | Tandala | EBOV | 1 | 1 | 100% | [85][93] |

| May–Jul 1995 | Zaire | Kikwit | EBOV | 315 | 254 | 81% | [94] |

| Aug–Nov 2007 | Democratic Republic of the Congo | Kasai-Occidental | EBOV | 264 | 187 | 71% | [95] |

| Dec 2008–Feb 2009 | Democratic Republic of the Congo | Kasai-Occidental | EBOV | 32 | 14 | 45% | [96] |

| Jun–Nov 2012 | Democratic Republic of the Congo | Orientale | BDBV | 77 | 36 | 47% | [85] |

| Aug–Nov 2014 | Democratic Republic of the Congo | Tshuapa | EBOV | 66 | 49 | 74% | [97] |

| May–Jul 2017 | Democratic Republic of the Congo | Likati | EBOV | 8 | 4 | 50% | [98] |

| Apr–Jul 2018 | Democratic Republic of the Congo | Équateur Province | EBOV | 54 | 33 | 61% | [99] |

| Aug 2018–June 2020 | Democratic Republic of the Congo | Kivu | EBOV | 3,470 | 2,280 | 66% | [100] |

| June 2020–present | Democratic Republic of the Congo | Équateur Province | EBOV | 74 | 32 | ongoing | [101] |

See also

- 2017 Democratic Republic of the Congo Ebola virus outbreak

- 2014 Democratic Republic of the Congo Ebola virus outbreak

- West Africa Ebola virus epidemic

- 2018 Kivu Democratic Republic of the Congo Ebola virus outbreak

Notes

References

- "New Ebola outbreak declared in Democratic Republic of the Congo". World Health Organization. 8 May 2018. Retrieved 9 May 2018.

- "Ebola virus disease – Democratic Republic of the Congo". World Health Organization. 10 May 2018. Retrieved 11 May 2018.

- "Ebola outbreak in DRC ends: WHO calls for international efforts to stop other deadly outbreaks in the country". World Health Organization. Retrieved 24 July 2018.

- "EBOLA RDC - Evolution de la riposte de l'épidémie d'Ebola au Vendredi 13 juillet 2018". us13.campaign-archive.com. Retrieved 20 July 2018.

- "Ebola virus disease – Democratic Republic of the Congo: Disease outbreak news, 25 July 2018". ReliefWeb. Retrieved 26 July 2018.

- Jon Cohen (15 May 2018). "Hoping to head off an epidemic, Congo turns to experimental Ebola vaccine". Science. doi:10.1126/science.aau1857.

- "Democratic Republic of Congo: Ebola Virus Disease - External Situation Report 17: Declaration of End of Ebola Virus Disease Outbreak". ReliefWeb. Retrieved 26 July 2018.

- "We finally have an Ebola vaccine. And we're using it in an outbreak". Vox. 16 May 2018. Retrieved 10 July 2018.

- "Health officials contain Ebola's spread in the Congo". Washington Examiner. 6 July 2018. Retrieved 10 July 2018.

- "DRC: at least 17 people dead in confirmed Ebola outbreak". The Guardian. Reuters. 8 May 2018. Retrieved 9 May 2018.

- "New Ebola outbreak hits Africa as 2 cases confirmed in Congo". CBS News. Associated Press. 8 May 2018. Retrieved 9 May 2018.

- "WHO concerned as one Ebola case confirmed in urban area of Democratic Republic of the Congo". World Health Organization. Retrieved 17 May 2018.

- McKirdy, Euan; Senthilingam, Meera (18 May 2018). "WHO raises Ebola health risk to 'very high' in DRC". CNN. Retrieved 18 May 2018.

- "Ebola in DR Congo 'not yet global crisis'". BBC News. 18 May 2018. Retrieved 19 May 2018.

- "Democratic Republic of the Congo Ebola virus disease - External Situation Report 12" (PDF). World Health Organization. Retrieved 24 June 2018.

- "Media Advisory: Expected end of Ebola outbreak". ReliefWeb. Retrieved 23 July 2018.

- Editorial, Reuters (August 2018). "Congo declares new Ebola outbreak in eastern province". Reuters. Retrieved 1 August 2018.

- "WHO Director-General's opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19 - 10 April 2020". www.who.int. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

- "New outbreak declared in Equateur province". Médecins Sans Frontières. 4 June 2020. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- Bearak, Max (17 May 2018). "First confirmed urban Ebola case is a 'game changer' in Congo outbreak". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 17 May 2018.

- "Ebola Virus Disease: Democratic Republic of the Congo: External Situation Report 4" (PDF). World Health Organization. 20 May 2018. Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- "Ebola Virus Disease: Democratic Republic of the Congo: External Situation Report 3" (PDF). World Health Organization. 18 May 2018. Retrieved 18 May 2018.

- "Democratic Republic of the Congo Ebola virus disease" (PDF). World Health Organization. 25 May 2018. Retrieved 26 May 2018.

- "WHO and partners working with national health authorities to contain new Ebola outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo". World Health Organization. Retrieved 11 May 2018.

- "Ebola situation reports: Democratic Republic of the Congo". WHO.

- "EBOLA VIRUS DISEASE, Democratic Republic of Congo, External Situation Report 1" (PDF). WHO. 11 May 2018.

- "EBOLA VIRUS DISEASE, Democratic Republic of Congo, External Situation Report 2" (PDF). WHO. 14 May 2018.

- News, ABC. "Ebola vaccinations begin in rural Congo on Monday: Ministry". ABC News. Archived from the original on 31 May 2018. Retrieved 26 May 2018.

- "Democratic Republic of Congo: Ebola Virus Disease - External Situation Report 6". ReliefWeb. Retrieved 20 June 2018.

- "Democratic Republic of Congo: Ebola Virus Disease - External Situation Report 7". ReliefWeb. Retrieved 2 June 2018.

- "The Fight to Get a Vaccine to Center of Ebola Outbreak". The New York Times. 1 June 2018. Retrieved 2 June 2018.

- "Democratic Republic of Congo: Ebola Virus Disease - External Situation Report 8". ReliefWeb. Retrieved 5 June 2018.

- "Democratic Republic of Congo: Ebola Virus Disease - External Situation Report 9". ReliefWeb. Retrieved 9 June 2018.

- "Democratic Republic of Congo: Ebola Virus Disease - External Situation Report 10". ReliefWeb. Retrieved 12 June 2018.

- "Democratic Republic of Congo: Ebola Virus Disease - External Situation Report 11". ReliefWeb. Retrieved 19 June 2018.

- "Democratic Republic of Congo: Ebola Virus Disease - External Situation Report 13". ReliefWeb. Retrieved 26 June 2018.

- "Democratic Republic of Congo: Ebola Virus Disease - External Situation Report 14". ReliefWeb. Retrieved 4 July 2018.

- "Democratic Republic of Congo: Ebola Virus Disease - External Situation Report 15". ReliefWeb. Retrieved 12 July 2018.

- Hilse, Gwendolin (24 July 2018). "DR Congo declares Ebola outbreak over". DW. Retrieved 25 July 2018.

- "Statement on the 1st meeting of the IHR Emergency Committee regarding the Ebola outbreak in 2018". World Health Organization. Retrieved 18 May 2018.

- Anne Gulland; Louise Dewast (23 May 2018). "Congo at a knife edge as number of cases of Ebola continues to rise". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- "Congo, U.N. deploy specialists to tackle Ebola epidemic". Reuters. 13 May 2018. Retrieved 13 May 2018.

- CNN, Meera Senthilingam. "Congo Ebola outbreak: 5 experimental drugs to be tried". CNN. Retrieved 31 May 2018.

- "Nearly 700 get Ebola vaccine in Congo; more cases possible". Fox News. 1 June 2018. Retrieved 1 June 2018.

- "Ebola virus disease – Democratic Republic of the Congo". World Health Organization. Retrieved 3 June 2018.

- "Ebola : Le gouvernement de Malanje (Angola) ferme la frontière avec la RDC — Actualite.CD". Actualite.CD (in French). 4 June 2018. Retrieved 4 June 2018.

- Schlein, Lisa. "Official End to Congo Ebola Outbreak Seen Near". VOA. Retrieved 21 July 2018.

- "Two infected Ebola patients flee treatment center in Congo". CBS news. Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- "Ebola outbreak in DR Congo: Patients 'taken to church'". BBC. 23 May 2018. Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- Nebehay, Stephanie (24 May 2018). "Infection alert after dying Ebola patients taken to Congo prayer…". Reuters. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- "ProMED-mail post". www.promedmail.org. Retrieved 25 May 2018.

- Louise Dewast (31 May 2018). "At the center of Ebola in the Congo, worry and indifference coexist". Archived from the original on 1 June 2018. Retrieved 3 June 2018.

- Aaron Ross (25 May 2018). "Fear and suspicion hinder Congo medics in Ebola battle". Reuters. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- Miles, Tom (29 May 2018). "WHO's Congo Ebola plan assumes 100-300 cases over three months". Reuters. Retrieved 29 May 2018.

- Mühlberger, Elke (March 2007). "Filovirus replication and transcription". Future Virology. 2 (2): 205–215. doi:10.2217/17460794.2.2.205. PMC 3787895. PMID 24093048.

- "How Ebola got its name". The Spectator. 25 October 2014. Retrieved 20 May 2018.

- Newman, Patricia (2015). Ebola: Fears and Facts. Lerner Publishing Group. p. 4. ISBN 9781467792400. Retrieved 20 May 2018.

- "WHO Director General visits Ebola-affected areas in DR Congo". World Health Organization. Retrieved 14 May 2018.

- "Ebola outbreak: UK Public Health Rapid Support Team deploys to DRC". GOV.UK. Retrieved 21 May 2018.

- Patient Ligodi (22 May 2018). "Two more die of Ebola in Congo; seven new cases confirmed". Reuters. Retrieved 22 May 2018.

- "Wellcome pledges £2m after new Ebola outbreak confirmed | Wellcome". wellcome.ac.uk. Retrieved 11 May 2018.

- "WHO supports Ebola vaccination of high risk populations in the Democratic Republic of the Congo". World Health Organization. Retrieved 21 May 2018.

- Jason Burke (18 May 2018). "Ebola: two more cases confirmed in Mbandaka in DRC". The Guardian. Retrieved 22 May 2018.

- Saleh Mwanamilongo (21 May 2018). "Congo Ebola vaccination campaign begins with health workers". The Washington Post. Retrieved 22 May 2018.

- "Trump Is in a Coma on Public Health". Foreign Policy. Retrieved 8 June 2018.

- Adebayo, Bukola (10 May 2018). "Ebola: Nigeria begins screening of travelers from high-risk countries". CNN. Retrieved 11 May 2018.

- Ed Yong (21 May 2018). "Most Maps of the New Ebola Outbreak Are Wrong". The Atlantic. Retrieved 21 May 2018.

- J. A. Regule; et al. (2017). "A Recombinant Vesicular Stomatitis Virus Ebola Vaccine". New England Journal of Medicine. 376 (4): 330–41. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1414216. PMC 5408576. PMID 25830322.

- Ana Maria Henao-Restrepo; et al. (2017). "Efficacy and effectiveness of an rVSV-vectored vaccine in preventing Ebola virus disease: final results from the Guinea ring vaccination, open-label, cluster-randomised trial (Ebola Ça Suffit!)". Lancet. 389 (10068): 505–18. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32621-6. PMC 5364328. PMID 28017403.

- Wolfram G Metzger; Sarai Vivas-Martínez (2018). "Questionable efficacy of the rVSV-ZEBOV Ebola vaccine". Lancet. 391 (10125): 1021. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30560-9. PMID 29565013.

- Medaglini, Donata; Santoro, Francesco; Siegrist, Claire-Anne (October 2018). "Correlates of vaccine-induced protective immunity against Ebola virus disease". Seminars in Immunology. 39: 65–72. doi:10.1016/j.smim.2018.07.003. PMID 30041831.

- "Ebola Erupts Again in Africa, Only Now There's a Vaccine". The New York Times. 11 May 2018. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 11 May 2018.

- Aizenman, Nurith (15 May 2018). "Can The New Ebola Vaccine Stop The Latest Outbreak?". NPR.org. Retrieved 16 May 2018.

- "WHO planning for 'worst case scenario' over DRC Ebola outbreak". www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 14 May 2018.

- "19 dead in latest Congo Ebola outbreak: WHO". Reuters. 14 May 2018. Retrieved 14 May 2018.

- "Ebola outbreak: Experimental vaccinations to begin in DR Congo". BBC. 21 May 2018. Retrieved 21 May 2018.

- "Ebola virus disease – Democratic Republic of the Congo, Disease outbreak news". WHO. 23 May 2018.

- Erika Check Hayden (18 May 2018). "Experimental drugs poised for use in Ebola outbreak". Nature. 557 (7706): 475–476. Bibcode:2018Natur.557..475C. doi:10.1038/d41586-018-05205-x. PMID 29789732.

- Erika Check Hayden (25 February 2016). "Ebola survivor's blood holds promise of new treatment". Nature. doi:10.1038/nature.2016.19440.

- Davide Corti; et al. (2016). "Protective monotherapy against lethal Ebola virus infection by a potently neutralizing antibody". Science. 351 (6279): 1339–42. Bibcode:2016Sci...351.1339C. doi:10.1126/science.aad5224. PMID 26917593.

- "Notes for the record: Consultation on Monitored Emergency Use of Unregistered and Investigational Interventions for Ebola Virus Disease (EVD)" (PDF). World Health Organization. 17 May 2018. Retrieved 25 May 2018.

- "NIH begins testing Ebola treatment in early-stage trial". National Institutes of Health (NIH). 23 May 2018. Retrieved 25 May 2018.

- Burki, Talha Khan (July 2016). "Post-Ebola syndrome". The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 16 (7): 780–781. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00259-5. PMID 27352759.

- Rosello, Alicia; Mossoko, Mathias; Flasche, Stefan; Van Hoek, Albert Jan; Mbala, Placide; Camacho, Anton; Funk, Sebastian; Kucharski, Adam; Ilunga, Benoit Kebela; Edmunds, W John; Piot, Peter; Baguelin, Marc; Muyembe Tamfum, Jean-Jacques (3 November 2015). "Ebola virus disease in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, 1976-2014". eLife. 4. doi:10.7554/eLife.09015. PMC 4629279. PMID 26525597.

- "Years of Ebola Virus Disease Outbreaks". www.cdc.gov. 18 May 2018. Retrieved 22 May 2018.

- "Democratic Republic of the Congo". World Health Organization. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- "Democratic Republic of the Congo: WHO statistical profile" (PDF). World Health Organization. January 2015. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- "Ebola virus disease: Democratic Republic of the Congo: External Situation Report 22" (PDF). WHO. 8 June 2017. Retrieved 21 May 2018.

- "DRC: MSF Treats 17,000 People in One of the Largest National Cholera Outbreaks Ever". Médecins Sans Frontières. 27 September 2017. Archived from the original on 25 May 2018. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- "DRC: Fighting the Country's Worst Cholera Epidemic in Decades". Médecins Sans Frontières. 25 January 2018. Archived from the original on 25 May 2018. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- "Cholera – Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo". World Health Organization. 25 January 2018. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- Report of an International Commission (1978). "Ebola haemorrhagic fever in Zaire, 1976". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 56 (2): 271–293. ISSN 0042-9686. PMC 2395567. PMID 307456.

- Heymann, D. L.; et al. (1980). "Ebola Hemorrhagic Fever: Tandala, Zaire, 1977–1978". Journal of Infectious Diseases. 142 (3): 372–76. doi:10.1093/infdis/142.3.372. PMID 7441008.

- Khan, A. S.; Tshioko, F. K.; Heymann, D. L.; Le Guenno, B.; Nabeth, P.; Kerstiëns, B.; Fleerackers, Y.; Kilmarx, P. H.; Rodier, G. R.; Nkuku, O.; Rollin, P. E.; Sanchez, A.; Zaki, S. R.; Swanepoel, R.; Tomori, O.; Nichol, S. T.; Peters, C. J.; Muyembe-Tamfum, J. J.; Ksiazek, T. G. (1999). "The reemergence of Ebola hemorrhagic fever, Democratic Republic of the Congo, 1995. Commission de Lutte contre les Epidémies à Kikwit". The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 179 Suppl 1: S76–86. doi:10.1086/514306. ISSN 0022-1899. PMID 9988168.

- "Outbreak news. Ebola virus haemorrhagic fever, Democratic Republic of the Congo--update". Releve Epidemiologique Hebdomadaire. 82 (40): 345–346. 5 October 2007. ISSN 0049-8114. PMID 17918654.

- "WHO | End of Ebola outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo". www.who.int. Retrieved 22 May 2018.

- "Congo declares its Ebola outbreak over". Reuters. 15 November 2014. Retrieved 22 May 2018.

- "Democratic Republic of the Congo Ebola virus" (PDF). World Health Organization. Retrieved 22 May 2018.

- "Ebola virus disease – Democratic Republic of the Congo: Disease outbreak news, 25 July 2018". ReliefWeb. Retrieved 26 July 2018.

- "DR Congo's deadliest Ebola outbreak declared over". BBC News. 25 June 2020. Retrieved 25 June 2020.

- "Ebola: 74 cases reported in DRC's 11th outbreak". Outbreak News Today. 6 August 2020. Retrieved 7 August 2020.

Further reading

- Maganga, Gaël D.; Kapetshi, Jimmy; Berthet, Nicolas; Kebela Ilunga, Benoît; Kabange, Felix; Mbala Kingebeni, Placide; Mondonge, Vital; Muyembe, Jean-Jacques T.; Bertherat, Eric; Briand, Sylvie; Cabore, Joseph; Epelboin, Alain; Formenty, Pierre; Kobinger, Gary; González-Angulo, Licé; Labouba, Ingrid; Manuguerra, Jean-Claude; Okwo-Bele, Jean-Marie; Dye, Christopher; Leroy, Eric M. (27 November 2014). "Ebola Virus Disease in the Democratic Republic of Congo". New England Journal of Medicine. 371 (22): 2083–2091. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1411099. PMID 25317743.

- Laupland, Kevin B; Valiquette, Louis (May 2014). "Ebola Virus Disease". The Canadian Journal of Infectious Diseases & Medical Microbiology. 25 (3): 128–9. doi:10.1155/2014/527378. PMC 4173971. PMID 25285105.

- Kadanali, Ayten; Karagoz, G (2016). "An overview of Ebola virus disease". Northern Clinics of Istanbul. 2 (1): 81–86. doi:10.14744/nci.2015.97269. PMC 5175058. PMID 28058346.

- Nanclares, Carolina; Kapetshi, Jimmy; Lionetto, Fanshen; de la Rosa, Olimpia; Tamfun, Jean-Jacques Muyembe; Alia, Miriam; Kobinger, Gary; Bernasconi, Andrea (September 2016). "Ebola Virus Disease, Democratic Republic of the Congo, 2014". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 22 (9): 1579–1586. doi:10.3201/eid2209.160354. PMC 4994351. PMID 27533284.

- "Experimental Ebola vaccines elicit year-long immune response/NIH reports final data from large clinical trial in West Africa". National Institutes of Health (NIH). NIH.gov. 11 October 2017. Retrieved 20 May 2018.

- Kuhn, Jens; Andersen, Kristian; Baize, Sylvain; Bào, Yīmíng; Bavari, Sina; Berthet, Nicolas; Blinkova, Olga; Brister, J.; Clawson, Anna; Fair, Joseph; Gabriel, Martin; Garry, Robert; Gire, Stephen; Goba, Augustine; Gonzalez, Jean-Paul; Günther, Stephan; Happi, Christian; Jahrling, Peter; Kapetshi, Jimmy; Kobinger, Gary; Kugelman, Jeffrey; Leroy, Eric; Maganga, Gael; Mbala, Placide; Moses, Lina; Muyembe-Tamfum, Jean-Jacques; N'Faly, Magassouba; Nichol, Stuart; Omilabu, Sunday; Palacios, Gustavo; Park, Daniel; Paweska, Janusz; Radoshitzky, Sheli; Rossi, Cynthia; Sabeti, Pardis; Schieffelin, John; Schoepp, Randal; Sealfon, Rachel; Swanepoel, Robert; Towner, Jonathan; Wada, Jiro; Wauquier, Nadia; Yozwiak, Nathan; Formenty, Pierre (24 November 2014). "Nomenclature- and Database-Compatible Names for the Two Ebola Virus Variants that Emerged in Guinea and the Democratic Republic of the Congo in 2014". Viruses. 6 (11): 4760–4799. doi:10.3390/v6114760. PMC 4246247. PMID 25421896.

- Chippaux, Jean-Philippe (2014). "Outbreaks of Ebola virus disease in Africa: the beginnings of a tragic saga". Journal of Venomous Animals and Toxins Including Tropical Diseases. 20 (1): 44. doi:10.1186/1678-9199-20-44. PMC 4197285. PMID 25320574.

- Mulangu, Sabue; Alfonso, Vivian H; Hoff, Nicole A; Doshi, Reena H; Mulembakani, Prime; Kisalu, Neville K; Okitolonda-Wemakoy, Emile; Kebela, Benoit Ilunga; Marcus, Hadar; Shiloach, Joseph; Phue, Je-Nie; Wright, Linda L; Muyembe-Tamfum, Jean-Jacques; Sullivan, Nancy J; Rimoin, Anne W (15 February 2018). "Serologic Evidence of Ebolavirus Infection in a Population With No History of Outbreaks in the Democratic Republic of the Congo". The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 217 (4): 529–537. doi:10.1093/infdis/jix619. PMC 5853806. PMID 29329455.

- "Ebola Treatment Research | NIH: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases". www.niaid.nih.gov. National Institutes of Health. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- "WHO | WHO Regional Strategic EVD Readiness Preparedness Plan Regional Preparedness Plan for EVD in 9 Countries 31 May: follow up discussions". WHO. Retrieved 8 June 2018.

- Barry, Ahmadou; et al. (June 2018). "Outbreak of Ebola virus disease in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, April–May, 2018: an epidemiological study" (PDF). The Lancet. 392 (10143): 213–221. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31387-4. hdl:10044/1/61467. PMID 30047375.

- Mbala Kingebeni, Placide; Villabona-Arenas, Christian-Julian; Vidal, Nicole; Likofata, Jacques; Nsio-Mbeta, Justus; Makiala-Mandanda, Sheila; Mukadi, Daniel; Mukadi, Patrick; Kumakamba, Charles; Djokolo, Bathe; Ayouba, Ahidjo; Delaporte, Eric; Peeters, Martine; Muyembe Tamfum, Jean-Jacques; Ahuka Mundeke, Steve (2018). "Rapid confirmation of the Zaire Ebola Virus in the outbreak of the Equateur province in the Democratic Republic of Congo: implications for public health interventions". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 68 (2): 330–333. doi:10.1093/cid/ciy527. PMC 6321851. PMID 29961823.

- "Consultation on Monitored Emergency Use of Unregistered and Investigational Interventions for Ebola Virus Disease (EVD)". ReliefWeb. World Health Organization. Retrieved 9 July 2018.

External links

- World Health Organization Democratic Republic of the Congo crisis information

- World Health Organization Ebola situation reports

- "Ebola (Ebola Virus Disease) | CDC". www.cdc.gov. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 23 May 2018. Retrieved 28 May 2018.