ProMED-mail

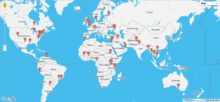

Program for Monitoring Emerging Diseases (also known as ProMED-mail, abbreviated ProMED) is among the largest publicly available emerging diseases and outbreak reporting systems in the world.[1] The central purpose of ProMED is to promote communication amongst the international infectious disease community, including scientists, physicians, veterinarians, epidemiologists, public health professionals, and others interested in infectious diseases on a global scale. Founded in 1994, ProMED has pioneered the concept of electronic, Internet-based emerging disease and outbreak detection reporting.[2] In 1999, ProMED became a program of the International Society for Infectious Diseases. As of 2016, ProMED has more than 75,000 subscribers in over 185 countries.[3] With an average of 13 posts per day, ProMED provides users with up-to-date information concerning infectious disease outbreaks on a global scale.

ProMED's guiding principles include:

- Transparency and a commitment to the unfettered flow of outbreak information

- Freedom from political constraints

- Availability to all without cost

- Commitment to One Health

- Service to the global health community

One of the essential global health priorities is the timely recognition and reporting of emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases. Early recognition can enable coordinated and rapid responses to an outbreak, preventing catastrophic morbidity and mortality. Additionally, early detection can alleviate grave economic hardship brought upon by pandemics and emerging diseases. Burgeoning globalization of commerce, finance, manufacturing, and services has fostered ever-increasing movement of people, animals, plants, food, and feed. Other contributing factors to the risk of new pathogens emerging and known pathogens re-emerging include climate change, urbanization, land use changes, and political instability. Outbreaks that begin in the most remote parts of the world now spread swiftly to urban centers in countries far away. The epidemiological data in ProMED posts has been used to estimate mortality rates and demographic parameters for specific diseases.[4][5]

The severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) outbreak in 2003 and the Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) outbreak in 2012 demonstrated the importance of early identification for emerging disease occurrences. The initial outbreak reports in both events were posted by astute clinicians. The use of non-traditional information sources can provide prompt information to the international community on emerging infectious disease problems that have yet to be officially reported.[6] The early dissemination of information may lead to rapid official confirmation of ongoing outbreaks. The Epicore program, launched in March 2016, makes use of volunteers throughout the world to find and report outbreaks using non-traditional methods.[7]

History

Under the auspices of the Federation of American Scientists, ProMED-mail was founded in 1994 by Dr. Stephen Morse, then of Rockefeller University, Dr. Barbara Rosenberg of the State University of New York at Purchase, and Dr. Jack Woodall, then of the New York State Department of Health (and currently an Associate Editor of ProMED).[8] Originally envisioned as a direct scientist-to-scientist network, ProMED rapidly grew into a prototype outbreak reporting and discussion list, especially after the 1995 Ebola outbreak. The idea of a global network was first proposed by Donald A. Henderson in 1989.[9]

ProMED played a crucial role in identifying the SARS outbreak early in 2003.[10] An astute physician in Silver Spring, Maryland, Stephen O. Cunnion, MD, PhD, MPH, submitted the first report to the database for this emerging outbreak, allowing the ProMED community to track the outbreak nearly two months in advance of the worldwide alert.[11] The email read: “Have you heard of an epidemic in Guangzhou? An acquaintance of mine . . . reports that the hospitals there have been closed and people are dying.” It was one month later before the Chinese government officially acknowledged the outbreak.

In 2012, the users of ProMED were again some of the first to identify the outbreak of MERS. A physician was responsible for identifying the outbreak and reporting the event to the ProMED community, which was posted online.[12] Eight days after the initial report, the Saudi Health Ministry announced the diagnosis of a new form of coronavirus.

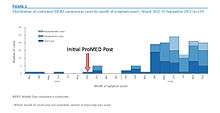

Again in late 2019 this alert was published on the site regarding a new outbreak of Undiagnosed Pneumonia was occurring in the city of Wuhan, Hubei, China: " Published Date: 2019-12-30 23:59:00 Subject: PRO/AH/EDR> Undiagnosed pneumonia - China (HU): RFI Archive Number: 20191230.6864153

UNDIAGNOSED PNEUMONIA - CHINA (HUBEI): REQUEST FOR INFORMATION

A ProMED-mail post http://www.promedmail.org ProMED-mail is a program of the International Society for Infectious Diseases http://www.isid.org

[1] Date: 30 Dec 2019 Source: Finance Sina [machine translation] https://finance.sina.cn/2019-12-31/detail-iihnzahk1074832.d.html?from=wap

Wuhan unexplained pneumonia has been isolated test results will be announced [as soon as available]

On the evening of [30 Dec 2019], an "urgent notice on the treatment of pneumonia of unknown cause" was issued, which was widely distributed on the Internet by the red-headed document of the Medical Administration and Medical Administration of Wuhan Municipal Health Committee.

On the morning of [31 Dec 2019], China Business News reporter called the official hotline of Wuhan Municipal Health and Health Committee 12320 and learned that the content of the document is true.

12320 hotline staff said that what type of pneumonia of unknown cause appeared in Wuhan this time remains to be determined.

According to the above documents, according to the urgent notice from the superior, some medical institutions in Wuhan have successively appeared patients with pneumonia of unknown cause. All medical institutions should strengthen the management of outpatient and emergency departments, strictly implement the first-in-patient responsibility system, and find that patients with unknown cause of pneumonia actively adjust the power to treat them on the spot, and there should be no refusal to be pushed or pushed.

The document emphasizes that medical institutions need to strengthen multidisciplinary professional forces such as respiratory, infectious diseases, and intensive medicine in a targeted manner, open green channels, make effective connections between outpatient and emergency departments, and improve emergency plans for medical treatment.

Another piece of emergency notification, entitled "City Health and Health Commission's Report on Reporting the Treatment of Unknown Cause of Pneumonia" is also true. According to this document, according to the urgent notice from the superior, the South China Seafood Market in our city has seen patients with pneumonia of unknown cause one after another.

The so-called unexplained pneumonia cases refer to the following 4 cases of pneumonia that cannot be diagnosed at the same time: fever (greater than or equal to 38C); imaging characteristics of pneumonia or acute respiratory distress syndrome; reduced or normal white blood cells in the early stages of onset The number of lymphocytes was reduced. After treatment with antibiotics for 3 to 5 days, the condition did not improve significantly.

It is understood that the 1st patient with unexplained pneumonia that appeared in Wuhan this time came from Wuhan South China Seafood Market.

12320 hotline staff said that the Wuhan CDC went to the treatment hospital to collect patient samples as soon as possible, specifically what kind of virus is still waiting for the final test results. Patients with unexplained pneumonia have done a good job of isolation and treatment, which does not prevent other patients from going to the medical institution for medical treatment. Wuhan has the best virus research institution in the country, and the virus detection results will be released to the public as soon as they are found.

-- Communicated by: ProMED-mail "

Disease surveillance and reporting

The importance of using unofficial sources of information for public health surveillance has become increasingly recognized.[14] Sometimes referred to as “event-based surveillance” or “epidemic intelligence,” informal disease reporting services, pioneered by ProMED, have become a crucial component of the overall global infectious disease surveillance picture.[15] According to the WHO Epidemic & Pandemic Alert & Response, more than 60% of the initial outbreak reports come from informal sources, including ProMED-mail.

ProMED-mail publishes reports to the website ProMEDmail.org in addition to sending e-mails to service subscribers. There is no cost for subscription to the reporting network. ProMED encourages subscribers to contribute data, respond to requests for information, and collaborate in outbreak investigations and prevention efforts.

Posts are published on a real-time basis. Reports detail infectious disease outbreaks with geotags and links to related media articles and other ProMED posts. Each report is screened and edited by a staff of expert moderators, ensuring the validity of the published information. There are 45 moderators for ProMED stationed throughout the world. Moderators review reports submitted within their region of oversight, drawing on their knowledge of the region and infrastructure to provide accurate descriptions of the outbreak event.

As ProMED-mail is an independent program of the non-government, nonprofit International Society for Infectious Diseases, this ensures the avoidance of delay or suppression of disease reporting by governments for bureaucratic or strategic reasons. To provide access to a global audience, versions of ProMED are available in several languages and cover different regions, including ProMED-ESP (Spanish), ProMED-PORT (Portuguese), ProMED-RUS (Russian), ProMED-FRA (French), ProMED-MENA (Middle East and North Africa), ProMED-SoAs (South Asia and Arabic Summaries), as well as English-language versions ProMED-MBDS (Mekong Basin region of Southeast Asia) and ProMED-EAFR (Africa).

One Health

One Health is the principle that human, animal, and environmental health are inextricably linked and should no longer be researched and learned in a siloed manner.[16] ProMED embodied this concept in the sphere of infectious disease reporting since its inception. It is estimated that 70% of emerging human diseases originate in other animal species – termed zoonotic diseases. As diseases in both animal and agriculture species have health implications for humans, ProMED includes posts on emerging animal diseases and diseases related to agriculturally important plants due to their impact on human survival.

Collaborations

ProMED-mail and HealthMap were awarded a grant from Google.org's Predict and Prevent initiative in October 2008. This collaboration combined ProMED-mail's global network of human, animal, and ecosystem health specialists with HealthMap's digital detection efforts.

References

- Brownstein, John S.; Freifeld, Clark C.; Madoff, Lawrence C. (21 May 2009). "Digital Disease Detection — Harnessing the Web for Public Health Surveillance". New England Journal of Medicine. 360 (21): 2153–2157. doi:10.1056/NEJMp0900702. PMC 2917042. PMID 19423867.

- Times, Los Angeles. "Website for the germ-obsessed". latimes.com. Retrieved 20 May 2016.

- "ProMED-mail". www.promedmail.org. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- Nasner-Posso, KM; Cruz-Calderón, S; Montúfar-Andrade, FE; Dance, DA; Rodriguez-Morales, AJ (June 2015). "Human melioidosis reported by ProMED". International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 35: 103–6. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2015.05.009. PMC 4508390. PMID 25975651.

- Ince, Y; Yasa, C; Metin, M; Sonmez, M; Meram, E; Benkli, B; Ergonul, O (September 2014). "Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever infections reported by ProMED". International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 26: 44–6. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2014.04.005. PMID 24947424.

- Keller, M; Blench, M; Tolentino, H; Freifeld, CC; Mandl, KD; Mawudeku, A; Eysenbach, G; Brownstein, JS (May 2009). "Use of unstructured event-based reports for global infectious disease surveillance". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 15 (5): 689–95. doi:10.3201/eid1505.081114. PMC 2687026. PMID 19402953.

- "ProMED Experts Share their Insights on Disease Surveillance and EpiCore | Skoll Global Threats Fund". www.skollglobalthreats.org. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- Madoff, LC; Woodall, JP (2005). "The internet and the global monitoring of emerging diseases: lessons from the first 10 years of ProMED-mail". Archives of Medical Research. 36 (6): 724–30. doi:10.1016/j.arcmed.2005.06.005. PMID 16216654.

- Morse, SS (February 2014). "Public Health Disease Surveillance Networks". Microbiology Spectrum. 2 (1): OH–0002–2012. doi:10.1128/microbiolspec.OH-0002-2012. ISBN 9781555818425. PMID 26082122.

- Yong, Ed (2011). "Disease trackers". BMJ. 343: d4117. doi:10.1136/bmj.d4117. PMID 21729998.

- http://www.promedmail.org/post/2203332

- http://www.promedmail.org/post/1302733

- Eurosurveillance 2013: Volume 18 Issue 39 Article 3

- Chan, EH; Brewer, TF; Madoff, LC; Pollack, MP; Sonricker, AL; Keller, M; Freifeld, CC; Blench, M; Mawudeku, A; Brownstein, JS (14 December 2010). "Global capacity for emerging infectious disease detection". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 107 (50): 21701–6. doi:10.1073/pnas.1006219107. PMC 3003006. PMID 21115835.

- Keller, M; Blench, M; Tolentino, H; Freifeld, CC; Mandl, KD; Mawudeku, A; Eysenbach, G; Brownstein, JS (May 2009). "Use of unstructured event-based reports for global infectious disease surveillance". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 15 (5): 689–95. doi:10.3201/eid1505.081114. PMC 2687026. PMID 19402953.

- "ProMED-mail and ONE HEALTH" (PDF). One Health Initiative. Retrieved 20 May 2016.