Ewe people

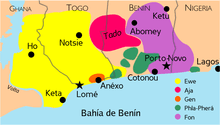

The Ewe people (Ewe: Eʋeawó, lit. "Ewe people"; or Mono Kple Volta Tɔ́sisiwo Dome, lit. "Ewe nation","Eʋenyigba" Eweland;[3]) are an African ethnic group. The largest population of Ewe people is in Ghana with (3.3m) people,[4] and the second largest population in Togo with (2m) people.[5][1] They speak the Ewe language (Ewe: Eʋegbe) which belongs to the Niger-Congo Gbe family of languages.[6] They are related to other speakers of Gbe languages such as the Fon, Gen, Phla Phera, and the Aja people of Togo and Benin.

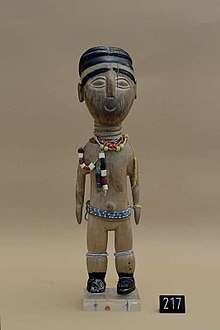

Ewe artwork | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| c. 6.7 million[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Languages | |

| Ewe, French, English | |

| Religion | |

| Christianity (50%),[2] Vodun traditional religion, Judaism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Other Gbe peoples |

Demographics

Ewe people are located primarily in the coastal regions of West Africa, in the region south and east of the Volta River to around the Mono River at Togo and Benin border, Southwestern part of Nigeria , close to the Atlantic Ocean,stretching from the Nigeria and Benin Border to Epe.[7] They are particularly found in Volta Region in southeastern Ghana (formerly British Togoland), southern Togo (formerly French Togoland),in southwestern parts of Benin,and in Southwestern part of[[ Nigeria ,although they are small groups compared to the other three{3}Most of which are settled in Badagry ( Lagos State)]].[4] The Ewe region is sometimes referred to as the Ewe nation or Eʋedukɔ́ region (Togoland in colonial literature).[1]

They consist of four groups based on their dialect and geographic concentration: the Anlo Ewe, the Mina, Anechɔ, Ʋedome(Danyi), Tongu or Tɔŋu. The literary language has been the Anlo sub-branch.[7]

History

The ancient history of the Ewe people is not recorded.[4] they migrated from a place called Kotu or Amedzowe, east of the Niger River,[8][9] or that they are from the region that is now the border between Benin and Nigeria and then because of invasions and wars in the 17th century migrated into their current location.[1][7] Archaeological evidence suggests that the Ewe people likely had some presence in their current homelands at least earlier than the 13th century. This evidence dates their dynamism to a much earlier period than previously believed.[4] However, other evidence also suggests a period of turmoil, particularly when Yoruba warriors of Oyo Empire ruled the region. Their own oral tradition describes the brutal king Agɔ Akɔli or (Agor Akorli) of Notsie ruled from Kpalimé in 17th century.[4]

They share a history with people who speak Gbe languages. These speakers occupied the area between Akanland and Yorubaland. Previously some historians have tried to tie them to both Akan and Yoruba ethnic groups, but more recent studies suggest these are distinct ethnic groups that are neither Akan or Yoruba, although they appear to have both influenced and taken influence from the two ethnic groups.[10][11]

The Ewe[12] people had cordial relations with colonial-era European traders. However, in 1784, they warred with Danish colonial interests as Denmark attempted to establish coastal forts in Ewe regions for its officials and merchants.[7] The Ewes were both victims of slave raiding and trade, as well slave sellers to European slave merchants and ships.[7][13] Politically structured as chiefdoms, the Ewe people were frequently at war with each other, raided other clans within the Ewe people as well as in Ashantiland, and they sold the captives as slaves.[14]

After slavery was abolished and slave trade brought to a halt, the major economic activity of the Ewe people shifted to palm oil and copra exports. Their region was divided between the colonial powers, initially between the German and British colonies, and after World War I, their territories were divided between the British and a British-French joint protectorate.[7] After World War I, the British Togoland and French Togoland were respectively renamed Volta Region and Togo. The French Togoland was renamed Republic of Togo and gained independence from France on April 27, 1960.

There have been efforts to consolidate the Ewe peoples into one unified country since the colonial period, with many post-colonial leaders occasionally supporting their cause, but none have ultimately been successful.

.jpg)

Religion

Traditional religion

The sophisticated theology of the Ewe people is similar to those of nearby ethnic groups, such as the Fon religion. This traditional Ewe religion is called Voodoo. The word is borrowed from the Fon language, and means "spirit".[2] The Ewe religion holds Mawu as the creator god, who created numerous lesser deities (trɔwo) that serve as the spiritual vehicles and the powers that influence a person's destiny. This mirrors the Mawu and Lisa (Goddess and God) theology of the Fon religion, and like them, these are remote from daily affairs of the Ewe people. The lesser deities are believed to have means to grant favors or inflict harm.[14]

The Ewe have the concept of Si, which implies a "spiritual marriage" between the deity and the faithful. It is typically referred to as a suffix to a deity. Thus a Fofie-si refers to a faithful who has pledged to deity Fofie, just like a spouse would during a marriage.[15] Ancestral spirits are important part of the Ewe traditional religion, and shared by a clan.[14]

Christianity

Christianity arrived among the Ewe people with the colonial merchants and missionaries. Major missions were established after 1840, by European colonies. German Lutheran missionaries arrived in 1847.[16] Their ideas were accepted in the coastal areas, and Germans named their region Togoland, or Togo meaning 'beyond the sea' in Ewe language. Germans lost their influence in World War I, their Christian missions were forced to leave the Togoland, and thereafter the French and British missionaries became more prominent among the Ewe people.[14][16]

About 50% of the Ewe population, particularly belonging to the coastal urban area, has converted to Christianity. However, they continue to practice the traditional rites and rituals of their ancestral religion.[2][14]

Society and culture

The Ewe people are a patrilineal people who live in villages that contain lineages. Each lineage is headed by the male elder. The male ancestors have Ewe are revered, and traditionally, families can trace male ancestors. The land owned by an Ewe family is considered an ancestral gift, and they do not sell this gift.[7]

Ewe people are notable for their fierce independence and have lacked group identity, and they have never supported a concentration of power within a village or through a large state. Village decisions have been made by a collection of elders, and they have refused to politically support strong kings, after their experience with the 17th century powerful despot named Agokoli of Notse. This has led to a lack of state, and their inability to respond to jihads and wars that followed in and after 18th century. In regional matters, the chief traditional priest has been the primary power.[4] In contemporary times, the Ewes have attempted to connect and build a common culture and language-driven identity across the three countries where they are commonly found.[2]

While patrilineal, the Ewe women are traditionally the major merchants and traders, both at wholesale and retail level. Most shops and transactions are solely managed by women, and this include groceries to textiles.[7]

Another notable aspect of Ewe culture, state ethnologists such as Rosenthal and Venkatachalam, is their refusal to blame others, their "deep distress and voluntary acceptance of guilt" for their ancestor's role in the slave trade. They have gone to extraordinary lengths to commemorate former slaves midst them, and making the ancestors of the slaves to be revered deities as well.[17]

Music

The Ewe have developed a complex culture of music, closely integrated with their traditional religion. This includes drumming. Ewe believe that if someone is a good drummer, it is because they inherited a spirit of an ancestor who was a good drummer.

Ewe music has many genres. One is Agbekor, which relates to songs and music around war. These cover the range of human emotions associated with the consequence of war, from courage and solidarity inspired by their ancestors, to the invincible success that awaits Ewe warriors, to death and grief of loss.[18]

Cross-rhythm drumming is a part of Ewe musical culture.[19] In general, Ewe drums are constructed like barrels with wooden staves and metal rings, or carved from a single log. They are played with sticks and hands, and often fulfill roles that are traditional to the family. The 'child' or 'baby brother' drum, kagan, usually plays on the off beats in a repeated pattern that links directly with the bell and shaker ostinatos. The 'mother' drum, kidi, usually has a more active role in the accompaniment. It responds to the larger sogo or 'father' drum. The entire ensemble is led by the atsimevu or 'grandfather' drum, largest of the group.[20]

Lyrical songs are more prevalent in the southern region. In the north, flutes and drums generally take the place of the singer's voice.[20]

Dance

The Ewe have an intricate collection of dances, which vary between geographical regions and other factors. One such dance is the Adevu (Ade - hunting, Vu - dance). This is a professional dance that celebrates the hunter. They are meant both to make animals easier to hunt and to give animals a ritual "funeral" in order to prevent the animal's spirit from returning and harming the hunter.

Another dance, the Agbadza, is traditionally a war dance but is now used in social and recreational situations to celebrate peace. War dances are sometimes used as military training exercises, with signals from the lead drum ordering the warriors to move ahead, to the right, go down, etc. These dances also helped in preparing the warriors for battle and upon their return from fighting they would act out their deeds in battle through their movements in the dance.

The Atsiagbekor is a contemporary version of the Ewe war dance Atamga (Great (ga) Oath (atama) in reference to the oaths taken by people before proceeding into battle. The movements of this present-day version are mostly in platoon formation and are not only used to display battle tactics, but also to energize and invigorate the soldiers. Today, Atsiagbekor is performed for entertainment at social gatherings and at cultural presentations.

The Atsia dance, which is performed mostly by women, is a series of stylistic movements dictated to dancers by the lead drummer. Each dance movement has its own prescribed rhythmic pattern, which is synchronized with the lead drum. "Atsia" in the Ewe language means style or display.

.jpg)

The Bobobo (originally "Akpese") is said to have been developed by Francis Kojo Nuatro. He is thought to have been an ex-police officer who organized a group in the middle to late 1940s. The dance has its roots from Wusuta and in the Highlife music popular across West African countries. Bobobo gained national recognition in the 1950s and 1960s because of its use at political rallies and the novelty of its dance formations and movements. It is generally performed at funerals and other social occasions. This is a social dance with a great deal of room for free expression. In general, the men sing and dance in the center while the women dance in a ring around them. There are "slow" and "fast" versions of Bobobo. The slow one is called Akpese and the fast one is termed to be Bobobo.

Agahu is both the name of a dance and of one of the many secular music associations (clubs) of the Ewe people of Togo, Dahomey, and in the south-eastern part of the Volta Region. Each club (Gadzok, Takada, and Atsiagbeko are other such clubs) has its own distinctive drumming and dancing, as well as its own repertoire of songs. A popular social dance of West Africa, Agahu was created by the Egun speaking people from the town of Ketonu in what is now Benin. From there it spread to the Badagry area of Nigeria, where Ewe Settlement mostly fisherman heard, adapted. In dancing the Agahu, two circles are formed; the men stay stationary with their arms out and then bend with a knee forward for the women to sit on. They progress around the circle until they arrive at their original partner.

Gbedzimido is a war dance mostly performed by the people of Mafi-Gborkofe and Amegakope in the Central Tongu district of Ghana's Volta Region. Gbedzimido has been transformed into a contemporary dance and is usually seen only on very important occasions like the Asafotu festival, celebrated annually by the Tongu people around December. The dance is also performed at the funerals of highly placed people in society, mostly men. Mafi-Gborkofe is a small farming village near Mafi-Kumase.

Gota uses the mystical calabash drum of Benin, West Africa. The calabash was originally called the "drum of the dead" and was played only at funerals. It is now performed for social entertainment. The most exciting parts of Gota are the synchronized stops of the drummers and dancers.

Tro-u is ancestral drum music that is played to invite ancestors to special sacred occasions at a shrine. For religious purposes, a priest or priestess would be present. There are fast and slow rhythms that can be called by the religious leader in order to facilitate communication with the spirit world. The bell rhythm is played on a boat-shaped bell in the north, but the southern region uses a double bell. The three drums must have distinct pitch levels in order to lock in.

Sowu is one of the seven different styles of drumming that belong to the cult of Yewe, adapted for stage. Yewe is the God of Thunder and lightning among the Ewe speaking people of Togo, Benin, and in south-eastern parts of the Volta Region. Yewe is a very exclusive cult and its music is one of the most developed forms of sacred music in Eweland.

Language: Eʋegbe

| Region between rivers Mono and Volta | |

|---|---|

| People | Eʋeawo |

| Language | Eʋegbe |

| Country | Eʋedukɔ |

Ewe, also written Evhe, or Eʋe, is a major dialect cluster of Gbe or Tadoid (Capo 1991, Duthie 1996) spoken in the southern parts of the Volta Region, in Ghana and across southern Togo,[21] to the Togo-Benin border by about three million people. Ewe belongs to the Gbe family of Niger-Congo. Gbe languages are spoken in an area that extends predominantly from Togo, Benin and as far as Western Nigeria to Lower Weme.[22]

Ewe dialects vary. Groups of villages that are two or three kilometres apart use distinct varieties. Nevertheless, across the Ewe-speaking area, the dialects may be broadly grouped geographically into coastal or southern dialects, e.g., Aŋlɔ, Tɔŋú Avenor, Watsyi and inland dialects characterised indigenously as Ewedomegbe, e.g., Lomé, Danyi, and Kpele etc. (Agbodeka 1997, Gavua 2000, Ansre 2000). Speakers from different localities understand each other and can identify the peculiarities of the different areas. Additionally, there is a written standard that was developed in the nineteenth century based on the regional variants of the various sub-dialects with a high degree of coastal content. With it, a standard colloquial variety has also emerged (spoken usually with a local accent), and is used very widely in cross-dialectal contact sites such as schools, markets, and churches.[20]

The storytellers use a dialect of Aŋlɔ spoken in Seva. Their language is the spoken form and hence does not necessarily conform to the expectations of someone familiar with the standard dialect. For instance, they use the form yi to introduce relative clauses instead of the standard written si, and yia 'this' instead of the standard written sia. They sometimes also use subject markers on the verb agreeing with the lexical NP subject while this is not written in the standard. A distinctive feature of the Aŋlɔ dialect is that the sounds made in the area of the teeth ridge are palatalised when followed by a high vowel. For instance, the verb tsi 'become old' is pronounced [tsyi] by the storyteller Kwakuga Goka.[20]

See also

References

- James Minahan (2002). Encyclopedia of the Stateless Nations: Ethnic and National Groups Around the World A-Z. ABC-CLIO. pp. 589–590. ISBN 978-0-313-07696-1.

- John A. Shoup III (2011). Ethnic Groups of Africa and the Middle East: An Encyclopedia: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 90. ISBN 978-1-59884-363-7.

- Basic Ewe for foreign students, p. 206.

- Anthony Appiah; Henry Louis Gates (2010). Encyclopedia of Africa. Oxford University Press. pp. 454–455. ISBN 978-0-19-533770-9.

- Ghana, CIA Factbook

- Éwé: A Language of Ghana, Ethnologue

- John A. Shoup III (2011). Ethnic Groups of Africa and the Middle East: An Encyclopedia: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. pp. 89–90. ISBN 978-1-59884-363-7.

- Kete Asante, Molefi; Mazama, Ama (2009). Encyclopedia of African Religion. SAGE. p. 250. ISBN 978-1-4129-3636-1.

- Jakob Spieth (2011). Ewe-Stämme. African Books Collective. p. 36. ISBN 978-9988-647-90-2.

- Flash of the Spirit: African & Afro-American Art & Philosophy, Robert Farris Thompson

- Translating the Devil: Religion and Modernity Among the Ewe in Ghana, Birgit Meyer

- "History: Here Is Why All Ewes Are Proud To Be Called Number 9". CelebritiesBuzzGh. 28 September 2019. Retrieved 25 October 2019.

- Meera Venkatachalam (2015). Slavery, Memory and Religion in Southeastern Ghana, c. 1850–Present. Cambridge University Press. pp. 2–8, 16–17. ISBN 978-1-316-36894-7.

- James Minahan (2002). Encyclopedia of the Stateless Nations: Ethnic and National Groups Around the World A-Z. ABC-CLIO. pp. 590–591. ISBN 978-0-313-07696-1.

- Meera Venkatachalam (2015). Slavery, Memory and Religion in Southeastern Ghana, c. 1850–Present. Cambridge University Press. pp. 3 with note 3. ISBN 978-1-316-36894-7.

- Toyin Falola; Daniel Jean-Jacques (2015). Africa: An Encyclopedia of Culture and Society. ABC-CLIO. p. 1210. ISBN 978-1-59884-666-9.

- Meera Venkatachalam (2015). Slavery, Memory and Religion in Southeastern Ghana, c. 1850–Present. Cambridge University Press. pp. 7–8. ISBN 978-1-316-36894-7.

- Jeff Todd Titon; Timothy J. Cooley; David Locke; et al. (2009). Worlds of Music: An Introduction to the Music of the World's Peoples, Shorter Version. Cengage. pp. 73–78, 83–84. ISBN 978-0-495-57010-3.

- Victor Kofi Agawu (1995). African Rhythm Hardback with Accompanying CD: A Northern Ewe Perspective. Cambridge University Press. pp. 200–202. ISBN 978-0-521-48084-0.

- Spieth, Jakob (2011). Ewe-Stämme. African Books Collective. ISBN 978-9988-647-90-2.

- "Ewe". Ghana Web. Ghana Web. Retrieved 24 September 2014.

- "Ethnicity Facts for Benin & Togo - AncestryDNA". www.ancestry.com. Retrieved 2020-05-25.

Further reading

- The Ewe People, Jakob Spieth (1906), A German Togo colony record

- Ewe (Heritage Library of African Peoples) by E. Ofori Akyea

- A handbook of Eweland: Volume I, edited by Francis Agbodeka

- A Handbook of Eweland: Volume II, edited by Kodzo Gavua

- The Ewe of Togo and Benin, A handbook of Eweland Volume III

- Eʋe Dukɔ ƒe Blemanyawo, Eŋlɔla: Charles Kɔmi Kudzɔdzi (Papavi Hogbedetɔ)

- African Rhythm: A Northern Ewe Perspective by Kofi Agawu

- Gahu: Traditional Social Music of the Ewe People

- Kpegisu: A War Drum of the Ewe by Godwin Agbeli

- Gahu: Traditional Social Music of Ewe People

- Amegbetɔa alo Agbezuge ƒe ŋutinya

External links

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. 10 (11th ed.). 1911. p. 40.

- Dzobo, N.K. (1997) [1973]. African proverbs : the moral value of Ewe proverbs. Guide to conduct (ebook, revised ed.). Cape Coast, Ghana: University of Cape Coast, Faculty of Education. OCLC 604717619.

- Cottrell, Anna (2007). Once Upon a Time in Ghana: Traditional Ewe Stories Retold in English. Troubador Publishing Ltd. ISBN 978-1-906221-58-4. — Traditional Ewe stories retold, in English