Efik people

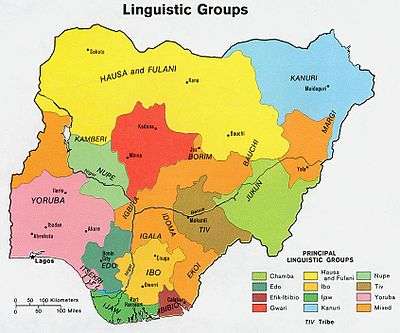

The Efik are a sub-ethnic group of Ibibio located primarily in southern Nigeria, in the southern part of Cross River State. The Efik speak the Efik language which is a Benue–Congo language of the Cross River family. Efik oral histories tell of migration down the Cross River from Arochukwu to found numerous settlements in the Calabar and Creek Town area. Creek Town and its environs are often commonly referred to as Calabar, and its people as Calabar people, after the European name Calabar Kingdom given to the state [in present-day Cross River State. Calabar is not to be confused with the Kalabari Kingdom in Rivers State which is an Ijaw state to its west. Cross River State with Akwa Ibom State was formerly one of the original twelve states of Nigeria known as the Southeastern State.

| |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 634,000[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Nigeria, Cameroon | |

| 615,000[1] | |

| 15,000[1] | |

| 4,400[1] | |

| Languages | |

| Efik, English, French | |

| Religion | |

| Christianity, Efik religion | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Ibibio, Annang, Ejagham (or Ekoi), Igbo and Ijaw | |

The Efik people also occupy southwestern Cameroon including Bakassi.[2] This area, formerly a trust territory from German Cameroon, was administered as a part of the Eastern Region of Nigeria until it achieved autonomy in 1954, thus separating the Efik people politically. This separation was further extended when as a result of a 1961 plebiscite the area voted to join the Republic of Cameroon. Most of the area was immediately transferred, but in August 2006 - Nigeria handed over the Bakassi peninsula to Cameroon.[3]

History

The Efik people are found in the South-South geopolitical zone of Nigeria, in “the South Eastern corner of the Cross River State.”[4] They occupy the basins of the Lower Cross River and down to the Bakassi Peninsula, the Calabar River and down to its tributaries – the Kwa River, Akpayafe (Akpa Ikang) and the Eniong Creek.”[5] They occupied Calabar “towards the end of the seventeenth century or at the beginning of the 18th century.”[6] The Efik are related to the Annang, Ibibio, Oron, Biase, Akamkpa, Uruan, and Eket people.

Although the actual origins of the Efik people are unknown, oral traditions provide accounts of their migration from Igbo and Ibibio territory (to the north-west of Calabar) to the present location. The bulk of them left to Uruan in present-day Akwa Ibom State, some to Eniong and surrounding areas. They stayed in Uruan for about a hundred or so years and then moved to Ikpa Ene and Ndodihi briefly before crossing over to their final destination in Creek Town (Esit Edik / Obio Oko). There would seem to be three successive stages in the history of efik migration and settlement: (a) an Igbo phase (b) an Ibibio phase and (c) the drift to the coast. The people of Uruan were said to have given them the name "Efik" deriving from a verb meaning to press or oppress, since they were alleged to be aggressive.

Although their economy was originally based on fishing, the area quickly developed into a major trading centre and remained so well into the early 1900s. Incoming European goods were traded for slaves, palm oil and other palm products. The Efik kings collected a trading tax called comey from docking ships until the British replaced it with 'comey subsidies'.[7] The diary of Antera Duke, an Efik, is the only surviving record from an African slave-trading house.[8]

The Efik were the middle men between the white traders on the coast and the inland tribes of the Cross River and Calabar district. Christian missions were at work among the Efiks beginning in the middle of the 19th century. Mary Slessor, a Presbyterian missionary from Scotland, was concerned with eliminating the superstitious practice of killing twin babies.[9] Even by 1900, many of the native peoples were well educated in European ideologies and culture, professed Christianity and dressed in European fashion.

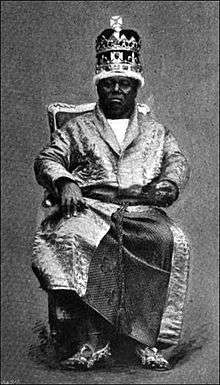

In 1884 the Efik kings and the chiefs of the Efik placed themselves under British protection. These treaties and attendant territorial economic rights, are documented in CAP 23 of Laws of Eastern Nigeria, captioned 'Comey subsidies law'.[7] The Efik king, also known as the Obong of Calabar, still (as of 2006) is a political power among the Efik.[10] The Efik and indeed the people of the Old Calabar kingdom were the first to embrace western education in present-day Nigeria, with the establishment of Hope Waddel Training Institute, Calabar in 1895 and the Methodist Boys' High School, Oron in 1905.

Secret societies

A powerful bond of union among the Efik, and one that gives them considerable influence over other tribes, is the secret society known as the Ekpe,[11] the inventor of the Nsibidi, an ancient African script. This society was transformed into the Abakuá cult in Cuba, the Bonkó cult in Bioko and the Abakuya dance in mainland Equatorial Guinea. The Ekpe society is exclusive for male, while females have their own Ekpa society.[11] People of Efik descent are known as ñáñigos or carabalís in Cuba.

Language

The Efik people speak the Efik language, which is a Benue–Congo language of the Cross River family.[12][13][14]

Demographics

Efik populations are found in the following regions:

- Cross River State, Nigeria

- Akwa Ibom State, Nigeria

- Bioko, Equatorial Guinea

- Cuba and the West Indies

- Western Cameroon

- Ghana

- Benue (Efik-Ibibio people were fourth largest ethnic group of original settlers of Benue area of Nigeria)

Cuisine

Edikang Ikong is a vegetable soup that originated among the Efik.[15] Afang soup is another popular cuisine sort for all over the federation and beyond.

Dressing

Efik women's main dresses are the onyonyo and the ofod ukod anwang[16]. They are mostly used as bridal outfits. The onyonyo is a long gown. It has been suggested that the onyonyo’s resemblance of Victorian gowns is as a result of the influence of the Scottish missionary Mary Slessor. The ofod ukod anwang includes a sleeveless top and short skirt, both accessorized with coral beads and the ekpa ku kwa—fuzzy ornaments decorating the arms and legs. The wearer has arm and leg beads and a necklace of coral beads.

See also

- Efik mythology

- Akamkpa

- Annang

- Bakassi

- Eket

- Ikom

- Niger Delta

- Opobo

- Igbo people

- Ekoi people (also known as Ejagham)

References

- Joshua Project - Efik of Nigeria Ethnic People Profile

- "Efik Culture History, marriage, food, and belief of this adorable ethnic group". www-pulse-ng.cdn.ampproject.org. Retrieved 2019-04-19.

- "Sordid tale from Bakassi". guardian.ng. Retrieved 2019-04-19.

- Cook, T.L. (1985). An integrated phonology of Efik. Ph.D. Thesis. University of Leiden.

- Aye, E. U. (2000). The Efik people. Calabar: Glad Tidings Press.

- Nair, K. K. (1972). Politics and society in South Eastern Nigeria 1841 – 1906: A study of power, diplomacy and commerce in Old Calabar. Evanston: North-Western University Press.

- Fubara, Dagogo M.J. (5 March 2006) "Legendary legacies of Dappa-Biriye" The Tide Rivers State Newspaper Corp., Port Harcourt, Nigeria

- The Diary of Antera Duke: An Eighteenth-Century African Slave Trader. Oxford University Press; Reprint edition (4 Jun. 2012) ISBN 0199922837 ISBN 978-0199922833 by Stephen D. Behrendt (Author), A.J.H. Latham (Contributor), David Northrup (Contributor)

- "August 5: Mary Slessor". This Day in Presbyterian History. 5 August 2017. Retrieved 5 August 2017.

- Nwagbara, Friday (2 June 2006) "Efik monarch withholds blessing for South-South" The Tide Rivers State Newspaper Corp., Port Harcourt, Nigeria Archived 6 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine;

- Miller, Ivor; Ojong, Mathew (February 2013). "Ékpè 'leopard' society in Africa and the Americas: influence and values of an ancient tradition". Ethnic and Racial Studies. 36 (2): 266–281. doi:10.1080/01419870.2012.676200.

- Green, Margret Mackeson (1949). "The classification of West African tone languages: Igbo and Efik". Africa: Journal of the International African Institute. 19: 213–219. doi:10.2307/1156971. JSTOR 1156971.

- Faraclas, Nicholas (1988). "Nigerian Pidgin and the Languages of Southern Nigeria". Journal of Pidgin and Creole Languages. 3 (2): 177–197. doi:10.1075/jpcl.3.2.03far.

- Connell, Bruce (1997). "Classifying Cross River". In Maddieson, Ian; Hinnebusch, Thomas J. (eds.). Language history and linguistic description in Africa Location=Trenton, New Jersey. Africa World Press. pp. 17–25. ISBN 978-0-86543-631-2.

- "Trad Perfect! Recipe for an amazing Edikang Ikong Soup". Pulse Nigeria. May 20, 2015. Retrieved September 6, 2016.

- "Efik Women's Regal Dresses". Folio Nigeria. Retrieved 17 August 2020.

- Waddell (1846) Efik or Old Calabar Waddell, Old Calabar;

- This article incorporates text from the Calabar article in the Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition, a publication now in the public domain.

- Hackett, Rosalind I. J. Religion In Calabar. Print.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Efik people. |