Mithila (region)

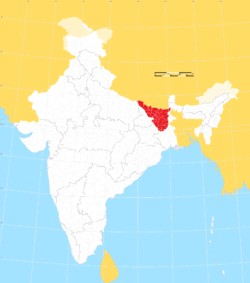

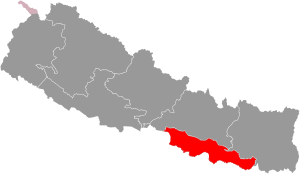

Mithila (IAST: Mithilā), also known as Tirhut and Tirabhukti, is a geographical and cultural region of the Indian subcontinent bounded by the Mahananda River in the east, the Ganges in the south, the Gandaki River in the west and by the foothills of the Himalayas in the north.[1][2] It comprises of certain parts of Bihar and Jharkhand of India[3] and adjoining districts of the eastern Terai of Nepal.[4][5]

Mithila | |

|---|---|

Region

Royal Insigna of Raj Darbhanga  Fort of Darbhanga | |

| Continent | Asia |

| Countries | India and Nepal |

| States or Provinces | Bihar and Jharkhand (India) and Province No. 2, Province No. 1 and Bagmati Pradesh (Nepal) |

| Language | Maithili |

The native language in Mithila is Maithili, and its speakers are referred to as Maithils.[1]

The name Mithila is commonly used to refer to the Videha Kingdom, as well as to the modern-day territories that fall within the ancient boundaries of Videha.[5] In the 18th century, when Mithila was still ruled in part by the Raj Darbhanga, the British Raj annexed the region without recognizing it as a princely state.[6][7]

History

Vedic period

Mithila first gained prominence after being settled by Indo-Aryan peoples who established the Videha kingdom.[8] During the Later Vedic period (c. 1100–500 BCE), Videha became one of the major political and cultural centers of South Asia, along with Kuru and Panchala. The kings of the Videha Kingdom were called Janakas.[9] The Videha Kingdom was later incorporated into the Vajji Confederacy, which had its capital in the city of Vaishali, which is also in Mithila.[10]

Medieval period

From the 11th century to the 20th century, Mithila was ruled by various indigenous dynasties. The first of these were the Karnatas, the Oiniwar Dynasty and the Khandwala Dynasty a.k.a. Raj Darbhanga. The rulers of the Oiniwar Dynasty and the Raj Darbhanga were Maithil Brahmins. It was during the reign of the Raj Darbhanga family that the capital of Mithila was shifted to Darbhanga.[11]

Tughlaq had attacked and taken control of Bihar, and from the end of the Tughlaq Dynasty until the establishment of the Mughal Empire in 1526, there was anarchy and chaos in the region. Akbar (reigned from 1556 to 1605) realised that taxes from Mithila could only be collected if there was a king who could ensure peace there. The Brahmins were dominant in the Mithila region and Mithila had Brahmin kings in the past.[citation needed]

Akbar summoned Rajpandit Chandrapati Thakur to Delhi and asked him to name one of his sons who could be made caretaker and tax collector for his lands in Mithila. Chandrapati Thakur named his middle son, Mahesh Thakur, and Akbar declared Mahesh Thakur as the caretaker of Mithila on the day of Ram Navami in 1557 AD.

Lakshmeshwar Singh (reigned from 1860 to 1898) was the eldest son of Maharaja Maheshwar Singh of Darbhanga. He, along with his younger brother, Rameshwar Singh received a western education from Government appointed tutors as well as a traditional Indian education from a Sanskrit Pandit. He spent approximately £300,000 on relief work during the Bihar famine of 1873–74. He constructed hundreds of miles of roads in various parts of the Raj, planting them with tens of thousands of trees for the comfort of travellers, as part of generating employment for people effected by famine. He constructed iron bridges over all the navigable rivers

He built, and entirely supported, a first-class Dispensary at Darbhanga, which cost £3400; a similar one at Kharakpur, which cost £3500; and largely contributed to many others.

He built an Anglo-vernacular school at a cost of £1490, which he maintained, as well as nearly thirty vernacular schools of different grades; and subsidised a much larger number of educational institutions. He was also one of the founders of Indian National Congress as well as one of the main financial contributor thereto Maharaja Lakshmeshwar Singh is known for purchasing Lowhter Castle for the venue of the 1888 Allahabad Congress session when the british denied permission to use any public place. The British Governor[who?] commissioned Edward Onslow Ford to make a statue of Lakshmeshwar Singh. This is installed at Dalhousie Square in Kolkata.

On the occasion of the Jubilee of the reign of Queen Victoria, Lakshmeshwar Singh was created a Knight Commander of the Most Eminent Order of the Indian Empire, being promoted to Knight Grand Commander in 1897. He was also a member of the Royal Commission on Opium of 1895, formed by British Government along with Haridas Viharidas Desai who was the Diwan of Junagadh. The Royal Opium Commission consisted of a 9-member team of which 7 were British and 2 were Indians and its chairman was Earl Brassey.

Geography

Mithila is a distinct geographical region with natural boundaries like rivers and hills. It is largely a flat and fertile alluvial plain criss-crossed by numerous rivers which originate from the Himalayas. Due to the flat plains and fertile land Mithila has a rich variety of biotic resources; however, because of frequent floods people could not take full advantage of these resources.[12]

Seven major rivers flow through Mithila: Mahananda, Gandak, Kosi, Bagmati, Kamala, Balan, and the Budhi Gandak.[13] They flow from the Himalayas in the north to the Ganges river in the south. These rivers regularly flood, depositing silt onto the farmlands and sometimes causing death or hardship.

Culture

Madhubani/Mithila Painting

Madhubani art or Mithila painting is practiced in the Mithila region of India and Nepal. It was traditionally created by the women of different communities of the Mithila region. It is named after Madhubani district of Bihar, India which is where it originated.[14]

This painting as a form of wall art was practiced widely throughout the region; the more recent development of painting on paper and canvas originated among the villages around Madhubani, and it is these latter developments that may correctly be referred to as Madhubani art.[15]

Mithila Paag

The Paag is a headdress in the Mithila region of India and Nepal worn by Maithil people. It is a symbol of honour and respect and a significant part of Maithil culture.

The Paag dates back to pre-historic times when it was made of plant leaves. It exists today in a modified form. The Paag is wore by the whole Maithil community .The colour of the Paag also carries a lot of significance. The red Paag is worn by the bridegroom and by those who are undergoing the sacred thread rituals. Paag of mustard colour is donned by those attending wedding ceremonies and the elders wear a white Paag.

This Paag now features place in the popular Macmillan Dictionary. For now, Macmillan Dictionary explains Paag as “a kind of headgear worn by people in the Mithila belt of India.” [16]

On 10 February 2017, India Posts released a set of sixteen commemorative postage stamps on "Headgears of India". The Mithila Paag was featured on one of those postage stamps.

Language

People of Mithila region speak Maithili primarily and are well versed in other languages like Hindi, Nepali, English, Bhojpuri for other different purposes.

While Maithilis living in Nepal also use Nepali language. And some also use Bengali language in significant part of Bihar-Bengal region.

This language is an Indo-Aryan language native to the Indian subcontinent, mainly spoken in India and Nepal and is one of the 22 recognised Indian languages. In Nepal, it is spoken in the eastern Terai and is the second most prevalent language of Nepal. Tirhuta was formerly the primary script for written Maithili. Less commonly, it was also written in the local variant of Kaithi. Today it is written in the Devanagari script.

Maithil Cuisine

Maithil cuisine is a part of Indian cuisine and Nepalese cuisine. It is a culinary style which originated in Mithila. Some traditional Maithil dishes are:

- Dahi-Chura

- Vegetable of Arikanchan

- Ghooghni

- Traditional Pickles, made of fruits and vegetables which are generally mixed with ingredients like salt, spices, and vegetable oils and are set to mature in a moistureless medium.

- Tarua of Tilkor

- Bada

- Badee

- Yogurt

- Maachh

- Mutton

- Irhar

- Pidakia ( also known as Gujia) which is basically dumplings.

- Makhan Payas

- Anarasa

- Bagiya

People

Maithili language speakers are referred to as Maithils and they are an Indo-Aryan ethno-linguistic group. There are an estimated 45 million Maithils in India alone. The vast majority of them are Hindu.[17]

The people of Mithila can be split into various caste/clan affiliations such as Brahmins, Bhumihars, Rajputs, Koeris, Baniyas, Kayasthas, Kamatas, Ahirs, Kurmis, Dushads, Koeris and many more.[18]

Notable people

The following are notable residents (past and present) of Mithila region.

Sharda Sinha

Sharda Sinha Shriti Jha in 2018

Shriti Jha in 2018 Bhawana Kanth in 2020

Bhawana Kanth in 2020

- Ramdhari Singh 'Dinkar' was an Indian Hindi poet, essayist, patriot and academic.[19]

- Bindheshwari Prasad Mandal was an Indian parliamentarian and social reformer who served as the chairman of the Second Backward Classes Commission (popularly known as the Mandal Commission).[20]

- C. K. Raut, formerly US-based computer scientist, author and political leader of Nepal.[21]

- Phanishwar Nath 'Renu', influential writer of modern Hindi literature in the post-Premchand era.[22]

- Syed Shahnawaz Hussain, Indian politician, born in Supaul[23][24][25]

- Janaka, King of Mithila and Father in Law of King Rama

- Sita, Princess of Mithila Kingdom and wife of King Rama

- Bhagwat Jha Azad was the Chief Minister of Bihar and a member of Lok Sabha.[26]

- Maithili Thakur, Indian singer

- Ram Baran Yadav, First president of Nepal

- Sharda Sinha, Indian folk singer

- Udit Narayan, Bollywood playback singer

- Kanhaiya Kumar, National executive Council member of Communist Party of India

- Narendra Jha, Bollywood actor

- Harisimhadeva, King of Mithila during the Karnat dynasty

- Sriti Jha, Indian television actress

- Kirti Azad, former Indian cricketer and politician

- Vidyapati, Maithili poet and a Sanskrit writer and a Polyglot

- Nagarjuna, Philosopher and poet-writer

- Sanjay Mishra, Bollywood actor

- Bhawana Kanth, one of the first female fighter pilots of India

- Gangesha Upadhyaya, 12th-century Indian mathematician and philosopher

- Ravish Kumar, Indian journalist

- Vikas Kumar Jha

- George Orwell, novelist and essayist, journalist and critic

- Rambriksh Benipuri, Indian freedom fighter, Socialist Leader, editor and Hindi writer

- Devaki Nandan Khatri, Indian writer

- Ganganath Jha, Indian scholar

- Ramjee Singh, former Member of Indian parliament and vice-chancellor of Jain Vishva Bharati University

- Acharya Ramlochan Saran, Hindi literature, grammarian and publisher

- Ramesh Chandra Jha, Indian poet, novelist and freedom fighter

- Binod Bihari Verma, Indian army man and poet

- Acharya Rameshwar Jha, scholar

- Phanishwar Nath 'Renu', Indian author

- Ravindra Prabhat a Hindi novelist, journalist, poet, and short story writer

- Gajendra Thakur, Literary critic, historian, novelist, dramatist, poet, and a lexicographer

- Anerood Jugnauth, former President of Mauritius

- Parmanand Jha, first Vice-President of Nepal

- Dhirendra Premarshi, presenter of Hello Mithila on Radio Kantipur

- Godawari Dutta, madhubani artist, social activist

Demands for administrative units

Proposed Indian state

There is an ongoing movement in the Maithili speaking region of Bihar and Jharkhand for a separate Indian state of Mithila.[27]

There is a movement in the Maithili speaking areas of Nepal for a separate province.[28] Province No. 2 was established under the 2015 Constitution, which transformed Nepal into a Federal Democratic Republic, with a total of 7 provinces. Province No. 2 has a substantial Maithili speaking population and consists most of the Maithili speaking areas of Nepal. It has been demanded by some Mithila activists that Province No. 2 be named 'Mithila Province'.[29]

See also

Notes

References

- Jha, M. (1997). "Hindu Kingdoms at contextual level". Anthropology of Ancient Hindu Kingdoms: A Study in Civilizational Perspective. New Delhi: M.D. Publications Pvt. Ltd. pp. 27–42.

- Mishra, V. (1979). Cultural Heritage of Mithila. Allahabad: Mithila Prakasana. p. 13.

- Jha, Pankaj Kumar (2010). Sushasan Ke Aaine Mein Naya Bihar. Bihar (India): Prabhat Prakashan. ISBN 9789380186283.

- Ishii, H. (1993). "Seasons, Rituals and Society: the culture and society of Mithila, the Parbate Hindus and the Newars as seen through a comparison of their annual rites". Senri Ethnological Studies 36: 35–84. Archived from the original on 23 August 2017.

- Kumar, D. (2000). "Mithila after the Janakas". The Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 60: 51–59.

- Singh, U. N. (1986). "The Maithili Language Movement: Successes and Failures". Language Planning: Proceedings of an Institute: 174–201.

- Jha, M. (1997). "Hindu Kingdoms at textual level". Anthropology of Ancient Hindu Kingdoms: A Study in Civilizational Perspective. New Delhi: M.D. Publications Pvt. Ltd.

- Michael Witzel (1989), Tracing the Vedic dialects in Dialectes dans les litteratures Indo-Aryennes ed. Caillat, Paris, pages 13, 17 116–124, 141–143

- Witzel, M. (1989). "Tracing the Vedic dialects". In Caillat, C. (ed.). Dialectes dans les litteratures Indo-Aryennes. Paris: Fondation Hugot. pp. 141–143.

- Hemchandra, R. (1972). Political History of Ancient India. Calcutta: University of Calcutta.

- Jha, Makhan (1997). Anthropology of Ancient Hindu Kingdoms: A Study in Civilizational Perspective. pp. 55–56. ISBN 9788175330344.

- Thakur, B.; Singh, D.P.; Jha, T. (2007). "The Folk Culture of Mithila". In Thakur, B.; Pomeroy, G.; Cusack, C.; Thakur, S.K. (eds.). City, Society, and Planning. Volume 2: Society. pp. 422–446.

- "Rivers of Bihar | Bihar Articles". Bihar.ws. Archived from the original on 23 July 2012. Retrieved 4 May 2012.

- Madhubani Painting. 2003. p. 96. ISBN 9788170171560. Archived from the original on 28 October 2017. Retrieved 20 February 2017.

- Carolyn Brown Heinz, 2006, "Documenting the Image in Mithila Art," Visual Anthropology Review, Vol. 22, Issue 2, pp. 5-33

- https://www.newindianexpress.com/nation/2019/dec/26/maithili-paag-finds-place-in-macmillan-dictionary-2081124.html

- James B. Minahan (30 August 2012). Ethnic Groups of South Asia and the Pacific: An Encyclopedia: An Encyclopedia. ISBN 9781598846607.

- Makhan Jha (1997). Anthropology of Ancient Hindu Kingdoms: A Study in Civilizational Perspective. pp. 33–40. ISBN 9788175330344.

- "Ramdhari Singh Dinker - Hindi ke Chhayavadi Kavi". www.anubhuti-hindi.org. Retrieved 26 April 2020.

- Nitish Kumar and the Rise of Bihar. Penguin Books India. 1 January 2011. ISBN 9780670084593.

- "" मुख्य समाचार " :: नेपाल ::". Ekantipur.com. 24 May 2015. Retrieved 28 May 2015.

- "Seasons India :: Hindi Literature of India". www.seasonsindia.com. Retrieved 26 April 2020.

- IANS (10 December 2013). "BJP's Shahnawaz Hussain on IM hit list". Business Standard India. Archived from the original on 26 October 2017. Retrieved 26 October 2017 – via Business Standard.

- "BJP leader Shahnawaz Hussain's impersonator arrested". NDTV.com. Archived from the original on 19 December 2013. Retrieved 26 October 2017.

- "PM's 'lack' of leadership has made UPA 'sinking ship': BJP". NewIndianExpress.com. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 26 October 2017.

- "8th Lok Sabha – Members Bioprofile – AZAD, SHRI BHAGWAT JHA". Archived from the original on 6 October 2011. Retrieved 6 August 2011.

- Kumāra, Braja Bihārī (1998). Small States Syndrome in India. p. 146. ISBN 9788170226918. Archived from the original on 17 February 2017. Retrieved 16 February 2017.

- Burkert, C. (2012). "Defining Maithil Identity". In Gellner, D.; Pfaff-Czarnecka, J.; Whelpton, J. (eds.). Nationalism and Ethnicity in a Hindu Kingdom: The Politics and Culture of Contemporary Nepal. London, New York: Routledge. pp. 241–273. ISBN 9781136649561. Archived from the original on 20 August 2017.

- "Samiti vows to protest for Mithila Province".

Bibliography

- Tukol, T. K. (1980). Compendium of Jainism. Dharwad: University of Karnataka.

- Shah, Umakant Premanand (1987). Jaina-Rupa Mandana: Jaina Iconography:, Volume 1. India: Shakti Malik Abhinav Publications. ISBN 978-81-7017-208-6.

External links

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Mithila. |