Unification of Nepal

Before the Shah dynasty united Nepal, only Kathmandu was known as Nepal or Nepal Mandala. After conquering all the small kingdoms of Nepal in the mid-eighteenth century, King Prithvi Narayan Shah moved his capital to Kathmandu from Gorkha and named the newly created empire, Nepal.

Establishment of expanded Gorkha kingdom

Gorkha was a small hilly kingdom with little wealth. After Prithvi Narayan Shah became king on 25 Chaitra 1799 BS, he started unification of Nepal. He began his campaign from Nuwakot.

Invasion of Nuwakot

Nara Bhupal Shah, Prithvi Narayan Shah's father, had already tried to invade Nuwakot in 1794 B.S. during his reign, and failed. At that time, Nuwakot was under the administrative control of Kantipur (today known as Kathmandu). Kantipur supported Nuwakot against the invasion. Following his defeat, Nara Bhupal Shah gave up his efforts and handed the administrative power over to Prithvi Narayan Shah and Chandraprabhawati (the eldest queen of Nara Bhupal Shah). Nara Bhupal Shah died in 1799 B.S. and Prithivi Narayan Shah ascended to the throne on 25 Chaitra 1799 B.S.

Nuwakot was the trade route between Tibet and Kathmandu, and the western gateway to Kathmandu valley. Prithvi Narayan Shah sent Gorkhali troops, under Kaji Biraj Thapa, to attack Nuwakot. Biraj Thapa waited at Khinchet by the side of Trishuli River for an appropriate time to launch the attack. Prithvi Narayan Shah didn't like the strategy of Biraj Thapa and began to mistrust him following the report by Maheshwor Panta. So, he sent another Gorkhali battlegroup under Maheshwor Panta. The troops under Maheshwor Panta were defeated.

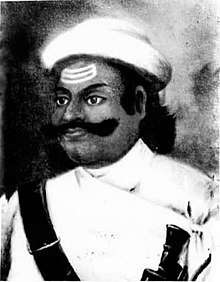

Kalu Pande was made the Commander-in-Chief of the Gorkhali Army after Biraj Thapa Magar and his first major Battle was the Battle of Kirtipur. Despite his initial resentment to the fact that the valley kings were well prepared and the Gorkhalis were not, Pande gave a 'Yes' to the operation, due to being insisted by Prithvi Narayan Shah. The Gorkhalis had set up a base on Naikap, a hill on the valley's western rim, from where they were to mount their assaults on Kirtipur. They were armed with swords, bows and arrows and muskets.[1]

The Valley Kings brought a large number of Doyas from Indian Plains under Shaktiballabh sardar. During the first assault in 1757, the Gorkhali army killed 1200 enemies, mostly Doyas, but were badly beaten themselves. Both sides suffered heavy losses. As they advanced towards Kirtipur, the combined force of Valley Kings under Kaji Gangadhar Jha, Kaji Gangaram Thapa and Sardar Shaktiballabh brought Havoc to the outnumbered Gorkhalis. The two forces fought on the plain of Tyangla Phant in the northwest of Kirtipur. Surapratap Shah, the King's brother lost his right eye to an arrow while scaling the city wall. The Gorkhali commander Kaji Kalu Pande was surrounded and killed, and the Gorkhali king himself narrowly escaped with his life into the surrounding hills disguised as a saint.[2][3]

After his conquest of the Kathmandu Valley, Prithvi Narayan Shah conquered other smaller territories south of the valley to keep other smaller fiefdoms near his Gurkha state out of the influence and control of British rule. After his kingdom spread from north to south, he made Kantipur the capital of expanded country, which was then known as Kingdom of Gorkha (Gorkha Samrajya).[4][5]

Shifting capital

Prithvi Narayan Shah in his Dibya Upadesh suggested a shift of the capital from Gorkha Durbar to Nepal.[6] The expanded Gorkha kingdom was renamed with the name of its capital.[7]

Battle of Kirtipur

Despite his initial resentment of Kaji Kalu Pande that the valley kings were well prepared and the Gorkhalis were not, Pande agreed for battle against the Kingdom of Kirtipur in the Kathmandu valley on being insisted from the monarch Prithvi Narayan Shah. The Gorkhalis had set up a base on Naikap to mount their assaults on Kirtipur. They were armed with swords, bows and arrows and muskets.[1] The two forces fought on the plain of Tyangla Phant in the northwest of Kirtipur. Surapratap Shah, the King's brother lost his right eye to an arrow while scaling the city wall. The Gorkhali commander Kaji Kalu Pande was surrounded and killed, and the Gorkhali king himself narrowly escaped with his life into the surrounding hills disguised as a saint.[8][3] In 1767, the King of Gorkha Prithvi Narayan sent his army to attack Kirtipur a third time under the command of Surpratap. In response, the three kings of valley joined forces and sent their troops to the relief of Kirtipur, but they could not dislodge the Gorkhalis from their positions. A noble of Lalitpur named Danuvanta crossed over to Shah's side and treacherously let the Gorkhalis into the town.[9][10]

Annexation of Makwanpur and Hariharpur

King Digbardhan Sen and his minister Kanak Singh Baniya had already sent their families to safer grounds before the encirclement of their fortress. The Gorkhalis launched an attack on 21 August 1762. The battle lasted for eight hours. King Digbardhan and his minister Kanak Singh escaped to Hariharpur Gadhi. Makawanpur was thus annexed to Nepal.[11]

After occupying the Makawanpur Gadhi fort, the Gorkhali forces started planning for an attack on Hariharpur Gadhi, a strategic fort on a mountain ridge of the Mahabharat range, also south of Kathmandu. It controlled the route to the Kathmandu valley. At the dusk of 4 October 1762, the Gorkhalis launched the attack. The soldiers at Hariharpur Gadhi fought valiantly against the Gorkha forces, but were ultimately forced to vacate the Gadhi after mid-night. About 500 soldiers of Hariharpur died in the battle.[11] Mir Qasim, the Nawab of Bengal extended his help to kings of Kathmandu valley with his forces to attack the Gorkhali forces. On 20 January 1763, Gorkhali commander Vamsharaj Pande won the battle against Mir Qasim.[12] Similarly, Captain Kinloch of British East India Company also extended his support by sending contingents against Gorkhalis. King Prithvi Narayan sent Kaji Vamsharaj Pande, Naahar Singh Basnyat, Jeeva Shah, Ram Krishna Kunwar and others to defeat the forces of Gurgin Khan at Makwanpur.[13][14]

Conquest of Kathmandu valley and Declaration of Kingdom of Nepal

The victory in the Battle of Kirtipur climaxed Shah's two-decade-long effort to take possession of the wealthy Kathmandu Valley. After the fall of Kirtipur, Shah took the other cities Kathmandu and Lalitpur in 1768 and Bhaktapur in 1769, completing his conquest of the valley.[9] In a letter to Ram Krishna Kunwar, King Prithvi Narayan Shah was unhappy at the death of Kaji Kalu Pande in Kirtipur and thought it was impossible to conquer Kathmandu valley after the death of Kalu Pande.[15] After the annexation of Kathmandu valley, King Prithvi Narayan Shah praised in his letter about valour and wisdom shown by Ramkrishna in annexation of Kathmandu, Lalitpur and Bhaktapur (i.e. Nepal valley at the time) on 1768-69 A.D.[16] Similarly, Vamsharaj Pande, Kalu Pande's eldest son, was the army commander who led attack of Gorkhali side on the Battle of Bhaktapur on 14 April 1769 A.D.[17]

Conquest of Kirant country

King Prithvi Narayan Shah had deployed Sardar Ram Krishna Kunwar to the invasion of Kirant regional areas comprising; Pallo Kirant (Limbuwan), Wallo Kirant and Majh Kirant (Khambuwan).[18] In 13th of Bhadra 1829 Vikram Samvat (i.e. 29 August 1772), Ram Krishna crossed Dudhkoshi river to invade King Karna Sen of Kirant and Saptari region[16] with fellow commander Abhiman Singh Basnyat.[19] He crossed Arun River to reach Chainpur.[20] Later, he achieved victory over Kirant region.[21] King Prithvi Narayan Shah bestowed 22 pairs of Shirpau (special headgear) in appreciation to Ram Krishna Kunwar after his victory over the Kirant region.[21]

Political Conflicts

On 1775, the conqueror king Prithvi Narayan Shah, who expanded Gorkha Kingdom to the Kingdom of Nepal died at Nuwakot.[22] Swarup Singh Karki, a shrewd Gorkhali courtier from a Chhetri family of Eastern Nepal,[23] marched with army to Nuwakot to confine Prince Bahadur Shah of Nepal who was then mourning the death of his father former King Prithvi Narayan Shah.[22] He confined Bahadur Shah and Prince Dal Mardan Shah with consent from newly reigning King Pratap Singh Shah who was considered to have no distinction of right and wrong.[22] In the annual Pajani (renewal) of that year, Swarup Singh was promoted to the position of Kaji along with Abhiman Singh Basnyat, Amar Singh Thapa and Parashuram Thapa.[22] In Falgun 1832 B.S., he succeeded in exiling Bahadur Shah, Dal Mardan Shah and Guru Gajraj Mishra on three heinous charges.[24] The reign of King Pratap Singh was characterized by the constant rivalry between Swarup and Vamsharaj Pande, a member of the leading Pande family of Gorkha.[25] The document dated Bikram Samvat 1833 Bhadra Vadi 3 Roj 6 (i.e. Friday 2 August 1776), shows that he had carried the title of Dewan along with Vamsharaj Pande.[26] King Pratap Singh Shah died on 22 November 1777 A.D.[27] leaving his infant son Rana Bahadur Shah as the King of Nepal.[28] Sarbajit Rana Magar was made a Kaji along with Balbhadra Shah and Vamsharaj Pande[29] while Daljit Shah was chosen as Chief Chautariya.[28][29] Historian Dilli Raman Regmi asserts that Sarbajit was chosen as Chief Kazi (equivalent to Prime Minister of Nepal).[28] Historian Rishikesh Shah asserts that Sarbajit was the head of the Nepalese government for a short period in 1778.[30] Afterwards, rivalry arose between Prince Bahadur Shah of Nepal and Queen Rajendra Laxmi. In the rivalry, Sarbajit led the followers of the Queen opposed to Sriharsh Pant who led the followers of Bahadur Shah.[31] The group of Bharadars (officers) led by Sarbajit poisoned the ears of Rajendra Laxmi against Bahadur Shah.[32] Rajendra Laxmi succeeded in the confinement of Prince Bahadur Shah with the help of her new minister Sarbajit.[33] Guru Gajraj Mishra came to rescue Bahadur Shah on the condition that Bahadur Shah should leave the country.[33][34] Also, his rival Sriharsh Pant was branded outcast and expelled instead of execution which was prohibited for Brahmins.[31]

Prince Bahadur Shah confined his sister-in-law Queen Rajendra Laxmi on the charge of having illicit relation with Sarbajit[35] on 31 August 1778.[27][36][37] Subsequently, Sarbajit was executed inside the palace by Prince Bahadur Shah[38][39] with the help of male servants of the royal palace.[38] Historian Bhadra Ratna Bajracharya asserts that it was actually Chautariya Daljit Shah who led the opposing group against Sarbajit Rana and Rajendra Laxmi.[40] The letter dated B.S. 1835 Bhadra Sudi 11 Roj 4 (1778 A.D.) to Narayan Malla and Vrajabasi Pande asserts the death of Sarbajit under misconduct and the appointment of Bahadur Shah as regent.[27] The death of Sarbajit Rana Magar is considered to have marked the initiation of court conspiracies and massacres in the newly unified Kingdom of Nepal.[34] Historian Baburam Acharya points that the sanctions against Queen Rajendra Laxmi under moral misconduct was a mistake of Bahadur Shah. Similarly, the murder of Sarbajit was condemned by many historians as an act of injustice.[41]

Vamsharaj Pande, once Dewan of Nepal and son of the popular commander Kalu Pande, was beheaded on the conspiracy of Queen Rajendra Laxmi with his support.[42][43] In the special tribunal meeting at Bhandarkhal garden, east of Kathmandu Durbar, Swaroop Singh held Vamsharaj liable for letting the King of Parbat, Kirtibam Malla to run away in the battle a year ago.[44] He had a fiery conversation with Vamsharaj before Vamsharaj was declared guilty and was subsequently executed by beheading on the tribunal.[31] Historian Rishikesh Shah and Ganga Karmacharya claim that he was executed on March 1785.[42][43] Bhadra Ratna Bajracharya and Tulsi Ram Vaidya claim that he was executed on 21 April 1785.[44][31] On 2 July 1785, his stiff opponent Prince Regent Bahadur Shah of Nepal was arrested and on the eleventh day of imprisonment on 13 July, his only supporter Queen Rajendra Laxmi died.[42][43] Then onwards, Bahadur Shah took over the regency of his nephew King Rana Bahadur Shah[45] and on the first moments of his regency ordered Swaroop Singh who was in Pokhara to be beheaded there [46][47] on the charges of treason.[48] He had gone to Kaski to join Daljit Shah's military campaign of Kaski fearing retaliation of the old courtiers due to his conspiracy against Vamsharaj. He was executed on 24th Shrawan 1842 B.S.[46]

Tibetan conflict

After the death of Prithvi Narayan Shah, the Shah dynasty began to expand their kingdom into what is present day North India. Between 1788 and 1791, Nepal invaded Tibet and robbed Tashi Lhunpo Monastery of Shigatse. Tibet sought Chinese help and the Qianlong Emperor of the Chinese Qing Dynasty appointed Fuk'anggan commander-in-chief of the Tibetan campaign. Heavy damages were inflicted on both sides. The Nepali forces retreated step by step back to Nuwakot to stretch Sino-Tibetan forces uncomfortably. Chinese launched uphill attack during the daylight and failed to succeed due to strong counterattack with Khukuri at Nuwakot.[49] The Chinese army suffered a major setback when they tried to cross a monsoon-flooded Betrawati, close to the Gorkhali palace in Nuwakot.[50] A stalemate ensued when Fuk'anggan was keen to protect his troops and wanted to negotiate at Nuwakot. The treaty was favouring more to Chinese side where Nepal had to send tributes to the Chinese emperor.[49]

See also

References

- Vansittart, Eden (1896). Notes on Nepal. Asian Educational Services. ISBN 978-81-206-0774-3. Page 34.

- Majupuria, Trilok Chandra (March 2011). "Kirtipur: The Ancient Town on the Hill". Nepal Traveller. Retrieved 18 October 2012.

- Wright, Daniel (1990). History of Nepal. New Delhi: Asian Educational Services. Retrieved 7 November 2012. Page 227.

- Joseph Bindloss (15 September 2010). Nepal. Lonely Planet Publications. p. 37. ISBN 978-1-74220-361-4.

- Less of a hero

- "Nepal Law Commission Dibya Upadesh" (PDF).

- "Nepāla Ki? Gorashā". 1955.

- Majupuria, Trilok Chandra (March 2011). "Kirtipur: The Ancient Town on the Hill". Nepal Traveller. Archived from the original on 17 November 2015. Retrieved 18 October 2012.

- Kirkpatrick, Colonel (1811). An Account of the Kingdom of Nepaul. London: William Miller. Retrieved 17 October 2012. Pages 382-386.

- "The city of good deeds". Nepali Times. 24–30 November 2000. Retrieved 18 October 2012.

- "History of the Nepalese Army". Nepalese Army. Archived from the original on 7 June 2011. Retrieved 7 October 2016.

- Vaidya 1993, p. 180.

- Hamal 1995, p. 202.

- Vaidya 1993, p. 151.

- Regmi 1972, p. 95.

- Vaidya 1993, p. 163.

- Hamal 1995, p. 180.

- Vaidya 1993, p. 165.

- Vaidya 1993, p. 167.

- Hamal 1995, p. 181.

- Bibhag 1990, p. 73.

- Singh 1997, p. 142.

- Bibhag 1990, p. 74.

- Shaha 1990, p. 43.

- D.R. Regmi 1975, p. 272.

- Karmacharya 2005, p. 36.

- D.R. Regmi 1975, p. 285.

- Shaha 1990, p. 46.

- Shaha 2001, p. 21.

- "Journal" (PDF). himalaya.socanth.cam.ac.uk.

- Rana 1978, p. 6.

- Mahesh Chandra Regmi 1975, p. 214.

- T.U. History Association 1977, p. 5.

- Regmi 1975, p. 215.

- D.R. Regmi 1975, p. 294.

- Bajracharya 1992, p. 21.

- Mahesh Chandra Regmi 1975, p. 215.

- Puratattva Bibhag 1990, p. 76.

- Bajracharya 1992, pp. 21-22.

- Bajracharya 1992, p. 22.

- Karmacharya 2005, p. 46.

- Shaha 2001, p. 62.

- Bajracharya 1992, p. 35.

- Pradhan 2012, p. 10.

- Bibhag 1990, p. 77.

- Shaha 2001, p. 63.

- Hamal 1995, p. 81.

- Stiller, L.F., "The Rise of the House of Gorkha." Patna Jesuit Society. Patna. 1975.

Further reading

- Fr. Giuseppe. (1799). An account of the kingdom of Nepal. Asiatic Researches. Vol 2. (1799). pp. 307–322.

- Reed, David. (2002). The Rough Guide to Nepal. DK Publishing, Inc.

- Wright, Daniel, History of Nepal. New Delhi-Madras, Asian Educational Services, 1990