Ahir

Ahir or Aheer is a community in India, most members of which identify as being of the Indian Yadav community because they consider the two terms to be synonymous.[1] The Ahirs are variously described as a caste, a clan, a community, a race and a tribe.

| Ahir/Aheer | |

|---|---|

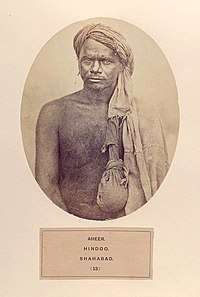

An Aheer in Shahabad, Bihar | |

| Religions | Hinduism |

| Languages | Varies depending on region |

| Populated states | India and Nepal |

| Subdivisions | Yaduvanshi, Nandvanshi, and Gwalvanshi Ahir |

The traditional occupations of Ahirs are cattle-herding and agriculture. They are found throughout India but are particularly concentrated in the northern areas. They are known by numerous other names, including Gauli,[2] and Ghosi or Gop in the north.[3] Some in the Bundelkhand region of Uttar Pradesh are known as Dauwa.[4]

Etymology

Gaṅga Ram Garg considers the Ahir to be a tribe descended from the ancient Abhira community, whose precise location in India is the subject of various theories based mostly on interpretations of old texts such as the Mahabharata and the writings of Ptolemy. He believes the word Ahir to be the Prakrit form of a Sanskrit word, Abhira, and he notes that the present term in the Bengali and Marathi languages is Abhir.[1]

Garg distinguishes a Brahmin community who use the Abhira name and are found in the present-day states of Maharashtra and Gujarat. That usage, he says, is because that division of Brahmins were priests to the ancient Abhira tribe.[1]

History

Early history

Theories regarding the origins of the ancient Abhira – the putative ancestors of the Ahirs – are varied for the same reasons as are the theories regarding their location; that is, there is a reliance on interpretation of linguistic and factual analysis of old texts that are known to be unreliable and ambiguous.[5]

Some, such as A. P. Karmakar, consider the Abhira to be a Proto-Dravidian tribe who migrated to India and point to the Puranas as evidence. Others, such as Sunil Kumar Bhattacharya, say that the Abhira are recorded as being in India in the 1st-century CE work, the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea. Bhattacharya considers the Abhira of old to be a race rather than a tribe.[5] The sociologist M. S. A. Rao and historians such as P. M. Chandorkar and T. Padmaja say that epigraphical and historical evidence exists for equating the Ahirs with the ancient Yadava tribe.[6][7][8]

Whether they were a race or a tribe, nomadic in tendency or displaced or part of a conquering wave, with origins in Indo-Scythia or Central Asia, Aryan or Dravidian – there is no academic consensus, and much in the differences of opinion relate to fundamental aspects of historiography, such as controversies regarding dating the writing of the Mahabharata and acceptance or otherwise of the Aryan invasion theory.[9] Similarly, there is no certainty regarding the occupational status of the Abhira, with ancient texts sometimes referring to them as pastoral and cowherders but at other times as robber tribes.[10]

Kingdoms

Ahir kingdoms included:

Military involvements

The British rulers of India classified the Ahirs of Punjab as an "agricultural tribe" in the 1920s, which was at that time synonymous with being a "martial race".[16] They had been recruited into the army from 1898.[17] In that year, the British raised four Ahir companies, two of which were in the 95th Russell's Infantry.[18] In post-independence India, some Ahir units have been involved in celebrated military actions, such as at Rezang La in the 1962 Sino-Indian War and in the 1965 India-Pakistan War.[19][20]

The Ahirs have been one of the more militant Hindu groups, including in the modern era.[21] It was from the 1920s that some Ahirs began to adopt the name of Yadav and various mahasabhas were founded by ideologues such as Rajit Singh. Several caste histories and periodicals to trace a Kshatriya origin were written at the time, notably by Mannanlal Abhimanyu. These were part of the jostling among various castes for socio-economic status and ritual under the Raj and they invoked support for a zealous, martial Hindu ethos.[22]

Subdivisions

They have more than 20 sub-castes.[23]

Distribution

Culture

Diet

In 1992, Noor Mohammad noted that most Ahirs in Uttar Pradesh were vegetarian, with some exceptions who were engaged in fishing and raising poultry.[28]

Folklore

The oral epic of Veer Lorik, a mythical Ahir hero, has been sung by folk singers in North India for generations. Mulla Daud, a Sufi Muslim, retold the romantic story in writing in the 14th century.[29] Other Ahir folk traditions include those related to Kajri and Biraha.[30]

Language and tradition

According to Alain Daniélou the ahirs belong to the same culture as the dark skinned prominent figures of the Ramayana and Mahabharata, Rama and Krishna. Ahirs of Benares speak a hindi dialect which is different from one used normally.[31][32] Ahirs usually speak language of the region in which they live. Some languages/Dialects named after Ahirs are Ahirani(Also known as Khandeshi) spoken in Khandesh region of Maharashtra, Ahirwati spoken in Ahirwal region of Haryana and Rajasthan. The Malwi spoken is Malwa region of Rajasthan and Madhya Pradesh is also known as Ahiri. These dialects are named after Ahirs but not necessarily only spoken by Ahirs living in those areas or all Ahirs in those regions speak these dialects[33]

The Ahirs have three major classifications Yaduvanshi, Nandavanshi and Goallavanshi. Yaduvanshi claim descent from Yadu, Nandavansh claim descent from Nanda, the foster father of Krishna and Goallavanshi claim descent from gopi and gopas of Krishna’s childhood.[34][35]

See also

References

- Garg, Gaṅga Ram, ed. (1992). Encyclopaedia of the Hindu world. 1. Concept Publishing Company. pp. 113–114. ISBN 978-81-7022-374-0.

- Mehta, B. H. (1994). Gonds of the Central Indian Highlands. II. New Delhi: Concept Publishing Company. pp. 568–569.

- Michelutti, Lucia (2002). "Sons of Krishna: the politics of Yadav community formation in a North Indian town" (PDF). PhD Thesis Social Anthropology. London School of Economics and Political Science. pp. 94–95.

- Jain, Ravindra K. (2002). Between History and Legend: Status and Power in Bundelkhand. Orient Blackswan. p. 30. ISBN 978-8-12502-194-0.

- Bhattacharya, Sunil Kumar (1996). Krishna – Cult in Indian Art. M.D. Publications. p. 126. ISBN 9788175330016.

- Guha, Sumit (2006). Environment and Ethnicity in India, 1200–1991. University of Cambridge. p. 47. ISBN 978-0-521-02870-7.

- Rao, M. S. A. (1978). Social Movements in India. 1. Manohar. pp. 124, 197, 210.

- T., Padmaja (2001). Temples of Kr̥ṣṇa in South India: History, Art, and Traditions in Tamilnāḍu. Archaeology Dept., University of Mysore. pp. 25, 34. ISBN 978-8-170-17398-4.

- Yadava, S. D. S. (2006). Followers of Krishna: Yadavas of India. Lancer Publishers. p. 1. ISBN 9788170622161.

- Malik, Aditya (1990). "The Puskara Mahatmya: A Short Report". In Bakker, Hans (ed.). The History of Sacred Places in India As Reflected in Traditional Literature. Leiden: BRILL and the International Association of Sanskrit Studies. p. 200. ISBN 9789004093188.

- Michelutti, Lucia (2002). "Sons of Krishna: the politics of Yadav community formation in a North Indian town" (PDF). PhD Thesis Social Anthropology. London School of Economics and Political Science. p. 83.

- Jalgaon district. "JALGAON HISTORY". Jalgaon District Administration Official Website. Jalgaon district Administration. Retrieved 7 February 2015.

- Yadav, Punam (2016). Social Transformation in Post-conflict Nepal: A Gender Perspective. Taylor & Francis. p. 57. ISBN 978-1-317-35389-8.

- Michelutti, Lucia (2002). "Sons of Krishna: the politics of Yadav community formation in a North Indian town" (PDF). PhD Thesis Social Anthropology. London School of Economics and Political Science. p. 47.

- Sharma, A N (2006). The Beria (Rai Dancers)A Socio-demographic, Reproductive, and Child Health Care Practices Profile. p. 13. ISBN 81-7625-714-1.

- Mazumder, Rajit K. (2003). The Indian army and the making of Punjab. Orient Blackswan. p. 105. ISBN 978-81-7824-059-6.

- Pinch, William R. (1996). Peasants and monks in British India. University of California Press. p. 90. ISBN 978-0-520-20061-6.

- Rao, M. S. A. (1979). Social movements and social transformation: a study of two backward classes movements in India. Macmillan.

- Guruswamy, Mohan (20 November 2012). "Don't forget the heroes of Rezang La". The Hindu. Retrieved 13 July 2014.

- Singh, Jasbir (2010). Combat Diary: An illustrated history of operations conducted by 4th Kumaon. History. Lancer Books. p. 212. ISBN 978-1-935501-18-3.

- Gooptu, Nandini (2001). The Politics of the Urban Poor in Early Twentieth-Century India. Cambridge University Press. p. 307. ISBN 978-0-521-44366-1.

The Ahirs in particular who played an important role in militant Hinduism, retaliated strongly against the Tanzeem movement. In July,1930, about 200 Ahirs marched in procession to Trilochan, a sacred Hindu site and performed a religious ceremony in response to Tanzeem processions.

- Gooptu, Nandini (2001). The Politics of the Urban Poor in Early Twentieth-Century India. Cambridge University Press. pp. 205–210. ISBN 978-0-521-44366-1.

- Patel, Mahendra Lal (1997). Awareness in Weaker Section: Perspective Development and Prospects. M. D. Publications Pvt. Ltd. p. 33. ISBN 978-8-17533-029-0.

- Guru Nanak Dev University, Sociology Dept (2003). Guru Nanak Journal of Sociology. Sociology Department, Guru Nanak Dev University. pp. 5, 6.

- Verma, Dip Chand (1975). Haryana. National Book Trust, India.

- Sharma, Suresh K. (2006). Haryana: Past and Present. Mittal Publications. p. 40. ISBN 978-81-8324-046-8.

- The Vernacularisation of Democracy: Politics, Caste, and Religion in India. Routledge. 2008. pp. 41, 42. ISBN 978-0-415-46732-2.

- Mohammad, Noor (1992). New Dimensions in Agricultural ... p. 60. ISBN 9788170224037.

- "Spectrum". The Sunday Tribune. 1 August 2010. Retrieved 13 July 2014.

- Koskoff, Ellen, ed. (2008). The Concise Garland Encyclopedia of World Music: The Middle East, South Asia, East Asia, Southeast Asia. Routledge. p. 1026. ISBN 978-0-415-97293-2.

- .danielou, Alain (2005). The Beria (Rai Dancers)A Socio-demographic, Reproductive, and Child Health Care Practices Profile. p. 56. ISBN 9781594770487.

- Kirshna, Nanditha (2009). Book of Vishnu. p. 56. ISBN 9788184758658.

- Linguistic Survey of India - Volume 9, Part 2 - Page 50.

- Singh, Bhrigupati (2015). Poverty and the Quest for Life Spiritual and Material Striving in Rural India University of Chicago. p. 13. ISBN 9780226194684.

- Michelutti, Lucia (2002). Sons of Krishna: the politics of Yadav community formation in a North Indian town (PDF). p. 89.