Taoiseach

The Taoiseach (/ˈtiːʃəx/ (![]()

| Taoiseach | |

|---|---|

| |

| Department of the Taoiseach | |

| Style | Taoiseach Irish: A Thaoisigh |

| Member of | |

| Reports to | Oireachtas |

| Residence | Steward's Lodge |

| Seat | Government Buildings, Merrion Street, Dublin, Ireland |

| Nominator | Dáil Éireann |

| Appointer | President of Ireland |

| Term length | While commanding the confidence of the majority of Dáil Éireann. No term limits are imposed on the office. |

| Inaugural holder | Éamon de Valera[note 1] |

| Formation | 29 December 1937[note 1] |

| Deputy | Tánaiste |

| Salary | €207,590 annually[1] |

| Website | www |

|

|---|

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of the Republic of Ireland |

|

Administrative geography |

The word taoiseach (plural taoisigh, pronounced [t̪ˠiːʃʲɪɟ] TEE-shee) means "chief" or "leader" in Irish and was adopted in the 1937 Constitution of Ireland as the title of the "head of the Government, or Prime Minister".[note 2] Taoiseach is the official title of the head of government in both English and Irish, and is not used for other countries' prime ministers (who are referred to in Irish as Príomh Aire, [ˌpˠɾˠiːvˠ ˈaɾʲə] pree-VAIR-ə). The Irish form, An Taoiseach, is sometimes used in English instead of "the Taoiseach".

Micheál Martin TD is the current Taoiseach; he took office on 27 June 2020, following a coalition agreement between his party Fianna Fáil, Fine Gael, and the Green Party.[3]

Overview

Under the Constitution of Ireland, the Taoiseach is nominated by a simple majority of the voting members of Dáil Éireann. They are then formally appointed to office by the President, who is required to appoint whomever the Dáil designates, without the option of declining to make the appointment. For this reason, the Taoiseach may, informally, be said to have been "elected" by Dáil Éireann.

If the Taoiseach loses the support of a majority in Dáil Éireann, they are not automatically removed from office. Instead, they are compelled either to resign or to persuade the President to dissolve the Dáil. If the President refuses to grant a dissolution, this effectively forces the Taoiseach to resign. To date, no president has exercised this prerogative, although the option arose in 1944 and 1994, and twice in 1982. The Taoiseach may lose the support of Dáil Éireann by the passage of a vote of no confidence, or implicitly, through the failure of a vote of confidence. Alternatively, the Dáil may refuse supply.[note 3] In the event of the Taoiseach's resignation, they continue to exercise the duties and functions of office until the appointment of a successor.

The Taoiseach nominates the remaining members of the Government, who are then, with the consent of the Dáil, appointed by the President. The Taoiseach is authorised to advise the President to dismiss cabinet ministers from office; by convention the President follows this advice. The Taoiseach is further responsible for appointing eleven members of the Seanad.

The Department of the Taoiseach is the government department which supports and advises the Taoiseach in carrying out their various duties.

Salary

Since 2013, the Taoiseach's annual salary is €185,350.[4] It was cut from €214,187 to €200,000 when Enda Kenny took office, before being cut further to €185,350 under the Haddington Road Agreement in 2013.

A proposed increase of €38,000 in 2007 was deferred when Brian Cowen became Taoiseach[5] and in October 2008, the government announced a 10% salary cut for all ministers, including the Taoiseach.[6] However this was a voluntary cut and the salaries remained nominally the same with both ministers and Taoiseach essentially refusing 10% of their salary. This courted controversy in December 2009 when a salary cut of 20% was based on the higher figure before the refused amount was deducted.[7] The Taoiseach is also allowed an additional €118,981 in annual expenses.

Residence

There is no official residence of the Taoiseach. In 2008 it was reported speculatively that the former Steward's Lodge at Farmleigh adjoining the Phoenix Park would become the official residence of the Taoiseach; however no official statements were made nor any action taken.[8] The house, which forms part of the Farmleigh estate acquired by the State in 1999 for €29.2m, was renovated at a cost of nearly €600,000 in 2005 by the Office of Public Works. Former Taoiseach Bertie Ahern did not use it as a residence, but his successor Brian Cowen used it occasionally.[9]

Salute

"Mór Chluana" ("More of Cloyne") is a traditional air collected by Patrick Weston Joyce in 1873.[10][11] "Amhrán Dóchais" ("Song of Hope") is a poem written by Osborn Bergin in 1913 and set to the air.[11][12] John A. Costello chose the air as his musical salute.[12] The salute is played by army bands on the arrival of the Taoiseach at state ceremonies. Though the salute is often called "Amhrán Dóchais", Brian Ó Cuív argues "Mór Chluana" is the correct title.[12][13]

History

Origins and etymology

The words Taoiseach and Tánaiste (the title of the deputy prime minister) are both from the Irish language and of ancient origin. Though the Taoiseach is described in the Constitution of Ireland as "the head of the Government or Prime Minister",[note 2] its literal translation is chieftain or leader.[14] Although Éamon de Valera, who introduced the title in 1937, was neither a Fascist nor a dictator, it has sometimes been remarked that the meaning leader in 1937 made the title similar to the titles of Fascist dictators of the time, such as Führer (Hitler), Duce (Mussolini) and Caudillo (Franco).[15][16][17] Tánaiste, in turn, refers to the system of tanistry, the Gaelic system of succession whereby a leader would appoint an heir apparent while still living.

In Scottish Gaelic, tòiseach translates as clan chief and both words originally had similar meanings in the Gaelic languages of Scotland and Ireland.[note 4][18][19][note 5] The related Welsh language word tywysog (current meaning: 'prince') has a similar origin and meaning.[note 6] It is hypothesized that both derive ultimately from the proto-Celtic *towissākos 'chieftain, leader'.[20][21]

The plural of taoiseach is taoisigh (Northern and Western Irish: [t̪ˠiːʃiː], Southern: [t̪ˠiːʃɪɟ]).[14]

Although the Irish form An Taoiseach is sometimes used in English instead of 'the Taoiseach',[22] the English version of the Constitution states that he or she "shall be called ... the Taoiseach".[note 2]

Debate on the title

In 1937 when the draft Constitution of Ireland was being debated in the Dáil, Frank MacDermot, an opposition politician, moved an amendment to substitute "Prime Minister" for the proposed "Taoiseach" title in the English text of the Constitution. It was proposed to keep the "Taoiseach" title in the Irish language text. The proponent remarked:[23]

It seems to me to be mere make-believe to try to incorporate a word like "Taoiseach" in the English language. It would be pronounced wrongly by 99 percent of the people. I have already ascertained it is a very difficult word to pronounce correctly. That being so, even for the sake of the dignity of the Irish language, it would be more sensible that when speaking English we should be allowed to refer to the gentleman in question as the Prime Minister... It is just one more example of the sort of things that are being done here as if for the purpose of putting off the people in the North. No useful purpose of any kind can be served by compelling us, when speaking English, to refer to An Taoiseach rather than to the Prime Minister.

The President of the Executive Council, Éamon de Valera, gave the term's meaning as "chieftain" or "Captain". He said he was "not disposed" to support the proposed amendment and felt the word "Taoiseach" did not need to be changed. The proposed amendment was defeated on a vote and "Taoiseach" was included as the title ultimately adopted by plebiscite of the people.[24]

Modern office

The modern position of Taoiseach was established by the 1937 Constitution of Ireland and is the most powerful role in Irish politics. The office replaced the position of President of the Executive Council of the 1922–1937 Irish Free State.

The positions of Taoiseach and President of the Executive Council differed in certain fundamental respects. Under the Constitution of the Irish Free State, the latter was vested with considerably less power and was largely just the chairman of the cabinet, the Executive Council. For example, the President of the Executive Council could not dismiss a fellow minister on his own authority. Instead, the Executive Council had to be disbanded and reformed entirely to remove a member. The President of the Executive Council also did not have the right to advise the Governor-General to dissolve Dáil Éireann on his own authority, that power belonging collectively to the Executive Council.

In contrast, the Taoiseach created in 1937 possesses a much more powerful role. The holder of the position can both advise the President to dismiss ministers and dissolve Parliament on his own authority—advice that the President is almost always required to follow by convention.[note 7] His role is greatly enhanced because under the Constitution, he is both de jure and de facto chief executive. In most other parliamentary democracies, the head of state is at least the nominal chief executive, while being bound by convention to act on the advice of the cabinet. In Ireland, however, executive power is explicitly vested in the Government, of which the Taoiseach is the leader.

Since the Taoiseach is the head of government, and may remove ministers at will, many of the powers specified, in law or the constitution, to be exercised by the government as a collective body, are in reality at the will of the Taoiseach. The Government almost always backs the Taoiseach in major decisions, and in many cases often merely formalizes that decision at a subsequent meeting after it has already been announced. Nevertheless the need for collective decision making on paper acts as a safeguard against an unwise decision made by the Taoiseach.

Historically, where there have been multi-party or coalition governments, the Taoiseach has been the leader of the largest party in the coalition. One exception to this was John A. Costello, who was not leader of his party, but an agreed choice to head the government, because the other parties refused to accept then Fine Gael leader Richard Mulcahy as Taoiseach. In 2010 Taoiseach Brian Cowen, in the midst of highly unpopular spending cuts after the global financial crash, maintained his position as Taoiseach until new elections, but stood down as leader of Fianna Fáil and allowed Micheál Martin (who had resigned in protest at the way Cowen responded to the crises) to succeed him.

List of office holders

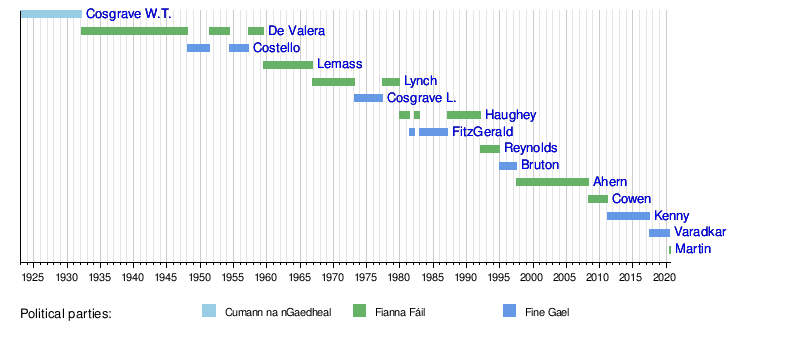

Before the enactment of the 1937 Constitution, the head of government was referred to as the President of the Executive Council. This office was first held by W. T. Cosgrave of Cumann na nGaedheal from 1922 to 1932, and then by Éamon de Valera of Fianna Fáil from 1932 to 1937. By convention, Taoisigh are numbered to include Cosgrave;[25][26][27][28] for example, Micheál Martin is considered the 15th Taoiseach, not the 14th.

President of the Executive Council | ||||||||||

| No. | Portrait | Name (Birth–Death) Constituency |

Term of office | Party | Exec. Council Composition |

Vice President | Dáil (elected) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |  |

W. T. Cosgrave (1880–1965) TD for Carlow–Kilkenny until 1927 TD for Cork Borough from 1927 |

6 December 1922[note 8] |

9 March 1932 |

Sinn Féin (Pro-Treaty) |

1st | SF (PT) (minority) | Kevin O'Higgins | 3 (1922) | |

| Cumann na nGaedheal | 2nd | CnG (minority) | 4 (1923) | |||||||

| 3rd | Ernest Blythe | 5 (Jun.1927) | ||||||||

| 4th | 6 (Sep.1927) | |||||||||

| 5th | ||||||||||

| 2 |  |

Éamon de Valera (1882–1975) TD for Clare |

9 March 1932[note 9] |

29 December 1937 |

Fianna Fáil | 6th | FF (minority) | Seán T. O'Kelly | 7 (1932) | |

| 7th | 8 (1933) | |||||||||

| 8th | 9 (1937) | |||||||||

Taoiseach | ||||||||||

| No. | Portrait | Name (Birth–Death) Constituency |

Term of office | Party | Government Composition |

Tánaiste | Dáil (elected) | |||

| (2) |  |

Éamon de Valera (1882–1975) TD for Clare |

29 December 1937 |

18 February 1948 |

Fianna Fáil | 1st | FF (minority) | Seán T. O'Kelly | 9 ( ···· ) | |

| 2nd | FF | 10 (1938) | ||||||||

| 3rd | FF (minority) | 11 (1943) | ||||||||

| 4th | FF | Seán Lemass | 12 (1944) | |||||||

| 3 | .jpg) |

John A. Costello (1891–1976) TD for Dublin South-East |

18 February 1948 |

13 June 1951 |

Fine Gael | 5th | FG–Lab–CnP–CnT–NL–Ind | William Norton | 13 (1948) | |

| (2) |  |

Éamon de Valera (1882–1975) TD for Clare |

13 June 1951 |

2 June 1954 |

Fianna Fáil | 6th | FF (minority) | Seán Lemass | 14 (1951) | |

| (3) | .jpg) |

John A. Costello (1891–1976) TD for Dublin South-East |

2 June 1954 |

20 March 1957 |

Fine Gael | 7th | FG–Lab–CnT | William Norton | 15 (1954) | |

| (2) |  |

Éamon de Valera (1882–1975) TD for Clare |

20 March 1957 |

23 June 1959 |

Fianna Fáil | 8th | FF | Seán Lemass | 16 (1957) | |

| 4 |  |

Seán Lemass (1899–1971) TD for Dublin South-Central |

23 June 1959 |

10 November 1966 |

Fianna Fáil | 9th | FF | Seán MacEntee | ||

| 10th | FF (minority) | 17 (1961) | ||||||||

| 11th | FF | Frank Aiken | 18 (1965) | |||||||

| 5 | .jpg) |

Jack Lynch (1917–1999) TD for Cork Borough until 1969 TD for Cork City North-West from 1969 |

10 November 1966 |

14 March 1973 |

Fianna Fáil | 12th | FF | |||

| 13th | FF | Erskine H. Childers | 19 (1969) | |||||||

| 6 |  |

Liam Cosgrave (1920–2017) TD for Dún Laoghaire and Rathdown |

14 March 1973 |

5 July 1977 |

Fine Gael | 14th | FG–Lab | Brendan Corish | 20 (1973) | |

| (5) | .jpg) |

Jack Lynch (1917–1999) TD for Cork City |

5 July 1977 |

11 December 1979 |

Fianna Fáil | 15th | FF | George Colley | 21 (1977) | |

| 7 |  |

Charles Haughey (1925–2006) TD for Dublin Artane |

11 December 1979 |

30 June 1981 |

Fianna Fáil | 16th | FF | |||

| 8 | .jpg) |

Garret FitzGerald (1926–2011) TD for Dublin South-East |

30 June 1981 |

9 March 1982 |

Fine Gael | 17th | FG–Lab (minority) | Michael O'Leary | 22 (1981) | |

| (7) |  |

Charles Haughey (1925–2006) TD for Dublin North-Central |

9 March 1982 |

14 December 1982 |

Fianna Fáil | 18th | FF (minority) | Ray MacSharry | 23 (Feb.1982) | |

| (8) | .jpg) |

Garret FitzGerald (1926–2011) TD for Dublin South-East |

14 December 1982 |

10 March 1987 |

Fine Gael | 19th | FG–Lab FG (minority) from Jan 1987 |

Dick Spring | 24 (Nov.1982) | |

| Peter Barry | ||||||||||

| (7) |  |

Charles Haughey (1925–2006) TD for Dublin North-Central |

10 March 1987 |

11 February 1992 |

Fianna Fáil | 20th | FF (minority) | Brian Lenihan | 25 (1987) | |

| 21st | FF–PD | 26 (1989) | ||||||||

| John Wilson | ||||||||||

| 9 | Albert Reynolds (1932–2014) TD for Longford–Roscommon |

11 February 1992 |

15 December 1994 |

Fianna Fáil | 22nd | FF–PD FF (minority) from Nov 1992 | ||||

| 23rd | FF–Lab FF (minority) from Nov 1994 |

Dick Spring | 27 (1992) | |||||||

| Bertie Ahern | ||||||||||

| 10 |  |

John Bruton (b. 1947) TD for Meath |

15 December 1994 |

26 June 1997 |

Fine Gael | 24th | FG–Lab–DL | Dick Spring | ||

| 11 |  |

Bertie Ahern (b. 1951) TD for Dublin Central |

26 June 1997 |

7 May 2008 |

Fianna Fáil | 25th | FF–PD (minority) | Mary Harney | 28 (1997) | |

| 26th | FF–PD | 29 (2002) | ||||||||

| Michael McDowell | ||||||||||

| 27th | FF–Green–PD | Brian Cowen | 30 (2007) | |||||||

| 12 |  |

Brian Cowen (b. 1960) TD for Laois–Offaly |

7 May 2008 |

9 March 2011 |

Fianna Fáil | 28th | FF–Green–PD FF–Green–Ind from Nov 2009 FF (minority) from Jan 2011 |

Mary Coughlan | ||

| 13 | .jpg) |

Enda Kenny (b. 1951) TD for Mayo |

9 March 2011 |

14 June 2017[29] |

Fine Gael | 29th | FG–Lab | Eamon Gilmore | 31 (2011) | |

| Joan Burton | ||||||||||

| 30th | FG–Ind (minority) | Frances Fitzgerald | 32 (2016) | |||||||

| 14 |  |

Leo Varadkar (b. 1979) TD for Dublin West |

14 June 2017[30] |

27 June 2020 |

Fine Gael | 31st | FG–Ind (minority) | |||

| Simon Coveney | ||||||||||

| 15 | .jpg) |

Micheál Martin (b. 1960) TD for Cork South-Central |

27 June 2020 |

Incumbent | Fianna Fáil | 32nd | FF–FG–Green | Leo Varadkar | 33 (2020) | |

Timeline

See also

Notes

- Before the enactment of the 1937 Constitution of Ireland, the head of government was referred to as the President of the Executive Council. This office was first held by W. T. Cosgrave from 1922 to 1932, and then by Éamon de Valera from 1932 to 1937.

- Article 13.1.1° and Article 28.5.1° of the Constitution of Ireland. The latter provision reads: "The head of the Government, or Prime Minister, shall be called, and is in this Constitution referred to as, the Taoiseach."

- One example of the Dáil refusing supply occurred in January 1982, when the then Fine Gael–Labour Party coalition government of Garret FitzGerald lost a vote on the budget.

- John Frederick Vaughan Campbell Cawdor (1742). Innes Cosmo (ed.). The book of the thanes of Cawdor: a series of papers selected from the charter room at Cawdor. 1236–1742, Volume 1236, Issue 1742. Spalding Club. p. xiii. Retrieved 23 June 2013.

As we cannot name the first Celtic chieftain who consented to change his style of Toshach and his patriarchal sway for the title and stability of King's Thane of Cawdor, so it is impossible to fix the precise time when their ancient property and offices were acquired.

- "Tartan Details – Toshach". Scottish Register of Tartans. Archived from the original on 2 December 2013. Retrieved 27 June 2013.

Toshach is an early Celtic title given to minor territorial chiefs in Scotland (note Eire Prime Minister's official title is this).

- John Thomas Koch (2006), Celtic Culture: a Historical Encyclopedia, ABC-CLIO, p. 1062, ISBN 1851094407,

An early word meaning 'leader' appears on a 5th- or 6th-century inscribed stone as both ogam Irish and British genitive TOVISACI: tywysog now means 'prince' in Welsh, the regular descriptive title used for Prince Charles, for example; while in Ireland, the corresponding Taoiseach is now the correct title, in both Irish and English, for the Prime Minister of the Irish Republic (Éire).

- Among the most famous ministerial dismissals have been those of Charles Haughey and Neil Blaney during the Arms Crisis in 1970, Brian Lenihan in 1990 and Albert Reynolds, Pádraig Flynn and Máire Geoghegan-Quinn in 1991.

- Cosgrave also headed the Irish Government from 22 August 1922, during the transitional period before the state became officially independent on 6 December 1922 (See Irish heads of government since 1919).

- De Valera also headed the pre-independence revolutionary Irish Government from 1 April 1919 to 9 January 1922 (See Irish heads of government since 1919).

References

- "Salaries, Houses of the Oireachtas". Oireachtas. Retrieved 2 November 2019.

- "Taoiseach". Oxford Dictionaries UK Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 30 November 2013.

- "33rd Dáil elects Micheál Martin as new Taoiseach". Irish Examiner. 27 June 2020. Retrieved 27 June 2020.

- "The Taoiseach, Ministers and every TD are having their pay cut today". TheJournal.ie. 4 July 2013. Retrieved 18 December 2013.

- "Taoiseach to receive €38k pay rise". RTÉ News. 25 October 2007.

- "Sharp exchanges in Dáil over Budget". RTÉ News. 15 October 2008. Retrieved 29 January 2009.

- "Opposition says Lenihan's salary cuts do not add up". Irish Independent. 10 December 2009. Retrieved 29 December 2009.

- "Opulent Phoenix Park lodge is set to become 'Fortress Cowen'". Irish Independent. 18 May 2008. Retrieved 18 May 2008.

- "Cowen questioned on use of Farmleigh". The Irish Times. 29 January 2009. Retrieved 29 January 2009.

- "P. W. Joyce: Ancient Irish Music » 47 – Mór Chluana". Na Píobairí Uilleann. Retrieved 3 February 2014.

- "Joyce, Patrick Weston (1827–1914)". Ainm.ie (in Irish). Cló Iar-Chonnacht. Retrieved 3 February 2014.

- Ó Cuív, Brian (1 April 2010). "Irish language and literature, 1845–1921". In W. E. Vaughan (ed.). Ireland Under the Union, 1870–1921. A New History of Ireland. VI. Oxford University Press. p. 425. ISBN 9780199583744. Retrieved 3 February 2014.

- "Amhrán Dóchais". Contemporary Music Centre. Retrieved 3 February 2014.

- "Youth Zone School Pack" (PDF). Department of the Taoiseach. Retrieved 23 June 2010.

- John-Paul McCarthy (10 January 2010). "WT became the most ruthless of them all". Irish Independent. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

While Taoiseach itself carried with it some initially unpleasant assonances with Caudillo, Fuhrer and Duce, all but one of the 12 men who wielded the prime ministerial sceptre have managed to keep their megalomaniacal tendencies in check.

- Martin Quigley, Jr (1944). Great Gaels: Ireland at Peace in a World at War. p. 18. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

Eamon de Valera is An Taoiseach or "boss Gael." That title goes considerably beyond the English "prime minister" or the American "president." It is the Gaelic equivalent of the German "Fuehrer," the Italian "Duce" and the Spanish "Caudillo."

Published in New York, 1944 (publisher not identified); Original from University of Minnesota; Digitized 6 May 2016 - Administration – Volume 18. Institute of Public Administration (Ireland). 1970. p. 153. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

... and let alone the names of the Prime Minister (the Taoiseach, a word that is related to Duce, Fuhrer, and Caudillo) (translated from the original Irish: ... agus fiú amháin ainmeacha an Phríomh-Aire (An Taoiseach, focal go bhfuil gaol aige le Duce, Fuhrer, agus Caudillo)

Original from the University of California; Digitized 6 December 2006 - E. William Robertson (2004). Scotland Under Her Early Kings: A History of the Kingdom to the Close of the Thirteenth Century Part One. Kessinger Publishing. p. 32. ISBN 9781417946075. Retrieved 28 June 2013.

- "DSL – SND1 TOISEACH". Archived from the original on 2 December 2013. Retrieved 27 June 2013.

- "Cambridge Medieval Celtic Studies". James Hall. 27 June 1992 – via Google Books.

- Bolling, George Melville; Bloch, Bernard (27 June 1968). "Language". Linguistic Society of America – via Google Books.

- "Statement by An Taoiseach on the death of Cardinal Desmond Connell". Department of the Taoiseach. 9 February 2017. Retrieved 5 March 2017.

The Taoiseach has learnt with regret ...

- Frank Mr. MacDermot of the Centre Party (Ireland) – Bunreacht na hÉireann (Dréacht)—Coiste (Ath-thógaint) – Wednesday, 26 May 1937; Dáil Éireann Debate Vol. 67 No. 9.

- – Bunreacht na hÉireann (Dréacht)—Coiste (Ath-thógaint) – Wednesday, 26 May 1937; Dáil Éireann Debate Vol. 67 No. 9.

- "Coughlan new Tánaiste in Cowen Cabinet". The Irish Times. 17 May 2008. Retrieved 17 May 2008.

- "Taoiseach reveals new front bench". RTÉ News. 7 May 2008. Retrieved 17 May 2008.

- "Cowen confirmed as Taoiseach". BreakingNews.ie. 7 May 2008. Retrieved 17 May 2008.

- "Former Taoisigh". Department of the Taoiseach. Archived from the original on 17 July 2011. Retrieved 23 June 2010.

- "Kenny's farewell: 'This has never been about me'". RTÉ News. 13 June 2017. Retrieved 14 June 2017.

- Lord, Miriam (8 June 2017). "Taoiseach-in-waiting meets man waiting to be taoiseach". The Irish Times. Retrieved 10 June 2017.

Further reading

The book Chairman or Chief: The Role of the Taoiseach in Irish Government (1971) by Brian Farrell provides a good overview of the conflicting roles for the Taoiseach. Though long out of print, it may still be available in libraries or from booksellers. Biographies are also available of de Valera, Lemass, Lynch, Cosgrave, FitzGerald, Haughey, Reynolds and Ahern. FitzGerald wrote an autobiography, while an authorised biography was produced of de Valera. There is a chapter by Garret FitzGerald on the role of the Taoiseach in a festschrift to Brian Farrell. There is a chapter by Eoin O'Malley on the Taoiseach and cabinet in Governing Ireland: From cabinet government to delegated governance (Eoin O'Malley and Muiris MacCarthaigh eds.) Dublin: IPA 2012.

- "David Gwynn Morgan: What exactly is a caretaker taoiseach?", The Irish Times, 8 March 2016

Biographies

Some biographies of former Taoisigh and presidents of the Executive Council:

- Tim Pat Coogan, Éamon de Valera

- John Horgan, Seán Lemass

- Brian Farrell, Seán Lemass

- T. P. O'Mahony, Jack Lynch: A Biography

- T. Ryle Dwyer, Nice Fellow: A Biography of Jack Lynch

- Stephen Collins, The Cosgrave legacy

- Garret FitzGerald, All in a Life

- Garret FitzGerald, "Just Garret: Tales from the Political Frontline"

- Raymond Smith, Garret: The Enigma

- T. Ryle Dwyer, Short Fellow: A Biography of Charles Haughey

- Martin Mansergh, Spirit of the Nation: The Collected Speeches of Haughey

- Joe Joyce & Peter Murtagh The Boss: Charles Haughey in Government

- Tim Ryan, Albert Reynolds: The Longford Leader

- Albert Reynolds, My Autobiography (Reviewed here)

- Bertie Ahern, My Autobiography (Reviewed here)