Kart dynasty

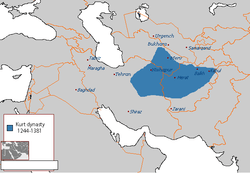

The Kart dynasty, also known as the Kartids, was a Sunni Muslim[1] dynasty of Tajik origin closely related to the Ghurids,[2] that ruled over a large part of Khorasan during the 13th and 14th centuries. Ruling from their capital at Herat and central Khorasan in the Bamyan, they were at first subordinates of Sultan Abul-Fateh Ghiyāṣ-ud-din Muhammad bin Sām, Sultan of the Ghurid Empire, of whom they were related,[3] and then as vassal princes within the Mongol Empire.[4] Upon the fragmentation of the Ilkhanate in 1335, Mu'izz-uddin Husayn ibn Ghiyath-uddin worked to expand his principality. The death of Husayn b. Ghiyath-uddin in 1370 and the invasion of Timur in 1381, ended the Kart dynasty's ambitions.[4]

Kart dynasty | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1244–1381 | |||||||||

The Kart dynasty at its greatest extent | |||||||||

| Status | Monarchy | ||||||||

| Capital | Herat | ||||||||

| Common languages | Persian | ||||||||

| Religion | Sunni Islam | ||||||||

| Malik/Sultan | |||||||||

• 1245 | Malik Rukn-uddin Abu Bakr (first) | ||||||||

• 1370–1389 | Ghiyas-uddin Pir 'Ali (last) | ||||||||

| Historical era | Middle Ages | ||||||||

• Foundation by Malik Rukn-uddin Abu Bakr | 1244 | ||||||||

• Disestablished | 1381 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | Afghanistan Iran Turkmenistan | ||||||||

Faravahar background | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History of Greater Iran | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Pre-Islamic BCE / BC

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Vassals of the Ghurid dynasty

The Karts trace their lineage to a Tajuddin Uthman Marghini, whose brother, 'Izzuddin Umar Marghini, was the Vizier of Sultan Ghiyāṣ-ud-din Muhammad bin Sām (d.1202-3).[5] The founder of the Kart dynasty was Malik Rukn-uddin Abu Bakr, who was descended from the Shansabani family of Ghur.[6]

Malik Rukn-uddin Abu Bakr married a Ghurid princess.[4] Their son Shams-uddin succeeded his father in 1245.

Vassals of the Mongol Empire

Shams-uddin Muhammad succeeded his father in 1245, joined Sali Noyan in an invasion of India in the following year, and met the Sufi Saint Baha-ud-din Zakariya at Multan in 1247-8. Later he visited the Mongol Great Khan Möngke Khan (1248–1257), who placed under his sway Greater Khorasan (present Afghanistan) and possibly region up to the Indus. In 1263-4, after having subdued Sistan, he visited Hulagu Khan, and three years later his successor Abaqa Khan, whom he accompanied in his campaign against Darband and Baku. He again visited Abaqa Khan, accompanied by Shams-uddin the Sahib Diwan, in 1276-7, and this time the former good opinion of the Mongol sovereign in respect to him seems to have been changed to suspicion, which led to his death, for he was poisoned in January 1278, by means of a water-melon given to him while he was in the bath at Tabriz. Abaqa Khan even caused his body to be buried in chains at Jam in Khorasan.

Fakhr-uddin was a patron of literature, but also extremely religious. He had previously been cast in prison by his father for seven years, until the Ilkhanid general Nauruz intervened on his behalf. When Nauruz's revolt faltered around 1296, Fakhr-uddin offered him asylum, but when an Ilkhanid force approached Herat, he betrayed the general and turned him over to the forces of Ghazan. Three years later, Fakhr-uddin fought against Ghazan's successor Oljeitu, who shortly after his ascension in 1306 sent a force of 10,000 to take Herat. Fakhr-uddin, however, tricked the invaders by letting them occupy the city, and then destroying them, killing their commander Danishmand Bahadur in the process. He died on 26 February 1307. But Herat and Gilan were conquered by Oljeitu.

Sham-suddin Muhammad was succeeded by his son Rukn-uddin. The latter adopted the title of Malik (Arabic for king), which all succeeding Kart rulers were to use. By the time of his death; in Khaysar on 3 September 1305, effective power had long been in the hands of his son Fakhr-uddin.

Fakhr-uddin's brother Ghiyath-uddin succeeded him upon his death; almost immediately, he began to quarrel with another brother, Ala-uddin ibn Rukn-uddin. Taking his case before Oljeitu, who gave him a grand reception, he returned to Khurasan in 1307/8. Continuing troubles with his brother led him to visit the Ilkhan again in 1314/5. Upon returning to Herat, he found his territories being invaded by the Chagatai prince Yasa'ur, as well as hostility from Qutb-uddin of Isfizar and the populace of Sistan. A siege of Herat was set by Yasa'ur. The prince, however, was stopped by the armies of the Ilkhanate, and in August 1320, Ghiyath-uddin made a pilgrimage to Mecca, leaving his son Shams-uddin Muhammad ibn Ghiyath-uddin in control during his absence. In 1327 the Amir Chupan fled to Herat following his betrayal by the Ilkhan Abu Sa'id Bahadur Khan, where he requested asylum from Ghiyath-uddin, whom he was friends with. Ghiyath-uddin initially granted the request, but when Abu Sa'id pressured him to execute Chupan, he obeyed. Soon afterwards Ghiyath-uddin himself died, in 1329. He left four sons: Shams-uddin Muhammad ibn Ghiyath-uddin, Hafiz ibn Ghiyath-uddin, Mu'izz-uddin Husayn ibn Ghiyath-uddin, and Baqir ibn Ghiyath-uddin.

Independent principality

Four years after Mu'izz-uddin Husayn ibn Ghiyath-uddin's ascension, the Ilkhan Abu Sa'id Bahadur Khan died, following which the Ilkhanate quickly fragmented. Mu'izz-uddin Husayn, for his part, allied with Togha Temür, a claimant to the Ilkhanid throne, and paid tribute to him. Up until his death, Mu'izz-uddin Husayn's main concern were the neighboring Sarbadars, centered in Sabzavar. As the Sarbadars were the enemies of Togha Temür, they considered the Karts a threat and invaded. When the Karts and Sarbadars met in the Battle of Zava on 18 July 1342, the battle was initially in the favor of the latter, but disunity within the Sarbadar army allowed the Karts to emerge victorious. Thereafter, Mu'izz-uddin Husayn undertook several successful campaigns against the Chagatai Mongols to the northeast. During this time, he took a still young Timur into his service. In 1349, while Togha Temür was still alive, Mu'izz-uddin Husayn stopped paying tribute to him, and ruled as an independent Sultan. Togha Temür's murder in 1353 by the Sarbadars ended that potential threat. Sometime around 1358, however, the Chagatai amir Qazaghan invaded Khurasan and sacked Herat. As he was returning home, Qazaghan was assassinated, allowing Mu'izz-uddin Husayn to reestablish his authority. Another campaign by the Sarbadars against Mu'izz-uddin Husayn in 1362 was aborted due to their internal disunity. Shortly afterwards, the Karts leader welcomed Shia dervishes fleeing from the Sarbadar ruler Ali-yi Mu'ayyad, who had killed their leader during the aborted campaign. In the meantime, however, relations with Timur became tense when the Karts launched a raid into his territory. Upon Mu'izz-uddin Husayn's death in 1370, his son Ghiyas-uddin Pir 'Ali inherited most of the Kart lands, except for Sarakhs and a portion of Quhistan, which Ghiyas-uddin's stepbrother Malik Muhammad ibn Mu'izz-uddin gained.

Vassals of the Timurids

Ghiyas-uddin Pir 'Ali, a grandson of Togha Temür through his mother Sultan Khatun, attempted to destabilize the Sarbadars by stirring up the refugee dervishes within his country. 'Ali-yi Mu'ayyad countered by conspiring with Malik Muhammad. When Ghiyas-uddin Pir 'Ali attempted to remove Malik Muhammad, 'Ali-yi Mu'ayyad flanked his army and forced him to abort the campaign, instead compromising with his stepbrother. The Sarbadars, however, soon suffered a period of internal strife, and Ghiyas-uddin Pir 'Ali took advantage of this by seizing the city of Nishapur around 1375 or 1376. In the meantime, both Ghiyas-uddin Pir 'Ali and Malik Muhammad had asked for the assistance of Timur regarding their conflict: the former had sent an embassy to him, while the latter had appeared before Timur in person as a requester of asylum, having been driven out of Sarakhs. Timur responded to Ghiyas-uddin Pir 'Ali by proposing a marriage between his niece Sevinj Qutluq Agha and the Kart ruler's son Pir Muhammad ibn Ghiyas-uddin, a marriage which took place in Samarkand around 1376. Later on, Timur invited Ghiyas-uddin Pir 'Ali to a council, so that the latter could submit to him, but when the Kart attempted to excuse himself from coming by claiming he had to deal with the Shia population in Nishapur, Timur decided to invade. He was encouraged by many Khurasanis, included Mu'izzu'd-Din's former vizier Mu'in al-Din Jami, who sent a letter inviting Timur to intervene in Khurasan, and the shaikhs of Jam, who, being very influential persons, had convinced many of the Kart dignitaries to welcome Timur as the latter neared Herat. In April 1381, Timur arrived before the city, whose citizens were already demoralized and also aware of Timur's offer not to kill anyone that did not take part in the battle. The city fell, its fortifications were dismantled, theologians and scholars were deported to Timur's homeland, a high tribute was enacted, and Ghiyas-uddin Pir 'Ali and his son were carried off to Samarkand. Ghiyas-uddin Pir 'Ali was made Timur's vassal, until he supported a rebellion in 1382 by the maliks of Herat. Ghiyas-uddin Pir 'Ali and his family were executed around 1383, and Timur's son Miran Shah destroyed the revolt. That same year, a new uprising led by a Shaikh Da'ud-i Khitatai in Isfizar was quickly put down by Miran Shah. The remaining Karts were murdered in 1396 at a banquet by Miran Shah.[7] The Karts therefore came to an end, having been the victims of Timur's first Persian campaign.

Rulers

| Titular Name | Personal Name | Reign | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Malik Rukn-uddin Abu Bakr | ?-1245 | ||

| Shams-uddin Muhammad bin Abu Bakr | 1245-1277 | ||

| Malik ملک Shams-uddin -i-Kihin |

Rukn-uddin ibn Sham-suddin Muhammad | 1277–1295 | |

| Malik ملک |

Fakhr-uddin ibn Rukn-uddin |

1295–1308 | |

| Malik ملک |

Ghiyath-uddin ibn Rukn-uddin |

1308–1329 | |

| Malik ملک |

Shams-uddin Muhammad ibn Ghiyath-uddin | 1329-1330 | |

| Malik ملک |

Hafiz ibn Ghiyath-uddin | 1330–1332 | Hafiz, a scholar and the next person to take the throne, was murdered after two years. |

| Malik ملک Sultan سلطان |

Mu'izz-uddin Husayn ibn Ghiyath-uddin | 1332–1370 | |

| Malik ملک Sultan سلطان |

Ghiyas-uddin Pir 'Ali & Malik Muhammad ibn Mu'izz-uddin under whom were initially Sarakhs and a portion of Quhistan |

1370–1389 | |

| Conquest of Greater Khorasan and Afghanistan by Amir Timur Beg Gurkani. | |||

The colored rows signify the following;

- Yellow – under Ghurid dynasty suzerainty

- Orange – under Mongol Empire and later Ilkhanate suzerainty

- Gray – Independent

- Pink – under Timurid suzerainty

See also

- List of Sunni Muslim dynasties

Notes

- Farhad Daftary, The Ismāī̀līs: Their History and Doctrines (Cambridge University Press, 1999), 445.

-

- Martijn Theodoor Houtsma (1993). "E.J. Brill's first Encyclopaedia of Islam, 1913-1936, Том 1". E.J. Brill p.546 pp.154. Retrieved 21 August 2017.

"The Kurt dynasty which ruled Afghanistan under the Persian Mongols were also Tadjiks. In the south, spreading into BalocistBn the population of Tadjik origin goes by the name of DehwSr or Dehkan, i. e. villager, and north of the Hindn- kush ..."

- Mukesh Kumar Sinha (2005). "The Persian World: Understanding People, Polity, and Life in Iran, Afghanistan, and Tajikistan". Hope India Publications p.151 pp.30. Retrieved 21 August 2017.

"The indigenous Kurt dynasty, a Tajik line related to the Ghurids"

- Mahomed Abbas Shushtery (1938). "Historical and cultural aspects". Bangalore Press pp.76. Retrieved 21 August 2017.

"The inhabitants of Seistan are a mixture of Tajiks and Baluchis. Some of them ... The Ghori and Kurt dynasties who ruled in Afghanistan were Tajiks ... "

- M. J. Gohari (2000). "The Taliban: Ascent to Power". Oxford University Press p.158 pp.4. Retrieved 21 August 2017.

"The indigenous Kert (Kurt) dynasty, a Tajik line related to the Ghurids, ruled at Herat"

- Farhad Daftary, The Ismāī̀līs: Their History and Doctrines, (Cambridge University Press, 1999), 445.

- Martijn Theodoor Houtsma (1993). "E.J. Brill's first Encyclopaedia of Islam, 1913-1936, Том 1". E.J. Brill p.546 pp.154. Retrieved 21 August 2017.

- M.J. Gohari, Taliban: Ascent to Power, (Oxford University Press, 2000), 4.

- C.E. Bosworth, The New Islamic Dynasties, (Columbia University Press, 1996), 263.

- Edward G. Browne, A Literary History of Persia: Tartar Dominion 1265-1502, (Ibex Publishers, 1997), 174.

- Kart, T.W. Haig and B. Spuler, The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Vol. IV, ed. E. van Donzel, B. Lewis and C. Pellat, (Brill, 1997), 672.

- Vasiliĭ Vladimirovich Bartolʹd, Four Studies on the History of Central Asia, Vol.II, (Brill, 1958), 33.

References

- Peter Jackson (1986). The Cambridge History of Iran, Volume Six: The Timurid and Safavid Periods. ISBN 0-521-20094-6

- Edward G. Browne (1926). A Literary History of Persia: The Tartar Dominion. ISBN 0-936347-66-X