Systems biology

Systems biology is the computational and mathematical analysis and modeling of complex biological systems. It is a biology-based interdisciplinary field of study that focuses on complex interactions within biological systems, using a holistic approach (holism instead of the more traditional reductionism) to biological research.[1] When it is crossing the field of systems theory and the applied mathematics methods, it develops into the sub-branch of complex systems biology.

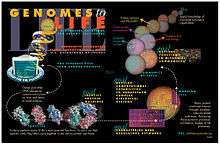

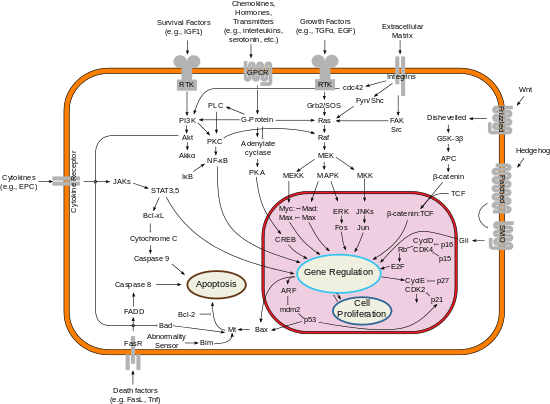

Particularly from year 2000 onwards, the concept has been used widely in biology in a variety of contexts. The Human Genome Project is an example of applied systems thinking in biology which has led to new, collaborative ways of working on problems in the biological field of genetics.[2] One of the aims of systems biology is to model and discover emergent properties, properties of cells, tissues and organisms functioning as a system whose theoretical description is only possible using techniques of systems biology.[3][1] These typically involve metabolic networks or cell signaling networks.[4][1]

Overview

Systems biology can be considered from a number of different aspects.

As a field of study, particularly, the study of the interactions between the components of biological systems, and how these interactions give rise to the function and behavior of that system (for example, the enzymes and metabolites in a metabolic pathway or the heart beats).[5][6][7]

As a paradigm, systems biology is usually defined in antithesis to the so-called reductionist paradigm (biological organisation), although it's fully consistent with the scientific method. The distinction between the two paradigms is referred to in these quotations: "The reductionist approach has successfully identified most of the components and many of the interactions but, unfortunately, offers no convincing concepts or methods to understand how system properties emerge ... the pluralism of causes and effects in biological networks is better addressed by observing, through quantitative measures, multiple components simultaneously and by rigorous data integration with mathematical models." (Sauer et al.)[8] "Systems biology ... is about putting together rather than taking apart, integration rather than reduction. It requires that we develop ways of thinking about integration that are as rigorous as our reductionist programmes, but different. ... It means changing our philosophy, in the full sense of the term." (Denis Noble)[7]

As a series of operational protocols used for performing research, namely a cycle composed of theory, analytic or computational modelling to propose specific testable hypotheses about a biological system, experimental validation, and then using the newly acquired quantitative description of cells or cell processes to refine the computational model or theory.[9] Since the objective is a model of the interactions in a system, the experimental techniques that most suit systems biology are those that are system-wide and attempt to be as complete as possible. Therefore, transcriptomics, metabolomics, proteomics and high-throughput techniques are used to collect quantitative data for the construction and validation of models.[10]

As the application of dynamical systems theory to molecular biology. Indeed, the focus on the dynamics of the studied systems is the main conceptual difference between systems biology and bioinformatics.[11]

As a socioscientific phenomenon defined by the strategy of pursuing integration of complex data about the interactions in biological systems from diverse experimental sources using interdisciplinary tools and personnel.[12]

This variety of viewpoints is illustrative of the fact that systems biology refers to a cluster of peripherally overlapping concepts rather than a single well-delineated field. However, the term has widespread currency and popularity as of 2007, with chairs and institutes of systems biology proliferating worldwide.

History

Systems biology finds its roots in the quantitative modeling of enzyme kinetics, a discipline that flourished between 1900 and 1970, the mathematical modeling of population dynamics, the simulations developed to study neurophysiology, control theory and cybernetics, and synergetics.

One of the theorists who can be seen as one of the precursors of systems biology is Ludwig von Bertalanffy with his general systems theory.[13] One of the first numerical simulations in cell biology was published in 1952 by the British neurophysiologists and Nobel prize winners Alan Lloyd Hodgkin and Andrew Fielding Huxley, who constructed a mathematical model that explained the action potential propagating along the axon of a neuronal cell.[14] Their model described a cellular function emerging from the interaction between two different molecular components, a potassium and a sodium channel, and can therefore be seen as the beginning of computational systems biology.[15] Also in 1952, Alan Turing published The Chemical Basis of Morphogenesis, describing how non-uniformity could arise in an initially homogeneous biological system.[16]

In 1960, Denis Noble developed the first computer model of the heart pacemaker.[17]

The formal study of systems biology, as a distinct discipline, was launched by systems theorist Mihajlo Mesarovic in 1966 with an international symposium at the Case Institute of Technology in Cleveland, Ohio, titled "Systems Theory and Biology".[18][19]

The 1960s and 1970s saw the development of several approaches to study complex molecular systems, such as the metabolic control analysis and the biochemical systems theory. The successes of molecular biology throughout the 1980s, coupled with a skepticism toward theoretical biology, that then promised more than it achieved, caused the quantitative modeling of biological processes to become a somewhat minor field.[20]

However, the birth of functional genomics in the 1990s meant that large quantities of high-quality data became available, while the computing power exploded, making more realistic models possible. In 1992, then 1994, serial articles [22][23][24][25][26] on systems medicine, systems genetics, and systems biological engineering by B. J. Zeng was published in China and was giving a lecture on biosystems theory and systems-approach research at the First International Conference on Transgenic Animals, Beijing, 1996. In 1997, the group of Masaru Tomita published the first quantitative model of the metabolism of a whole (hypothetical) cell.[27]

Around the year 2000, after Institutes of Systems Biology were established in Seattle and Tokyo, systems biology emerged as a movement in its own right, spurred on by the completion of various genome projects, the large increase in data from the omics (e.g., genomics and proteomics) and the accompanying advances in high-throughput experiments and bioinformatics. Shortly afterwards, the first departments wholly devoted to systems biology were founded (for example, the Department of Systems Biology at Harvard Medical School [28]).

In 2003, work at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology was begun on CytoSolve, a method to model the whole cell by dynamically integrating multiple molecular pathway models.[29] Since then, various research institutes dedicated to systems biology have been developed. For example, the NIGMS of NIH established a project grant that is currently supporting over ten systems biology centers in the United States.[30] As of summer 2006, due to a shortage of people in systems biology[31] several doctoral training programs in systems biology have been established in many parts of the world. In that same year, the National Science Foundation (NSF) put forward a grand challenge for systems biology in the 21st century to build a mathematical model of the whole cell. In 2012 the first whole-cell model of Mycoplasma genitalium was achieved by the Karr Laboratory at the Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York. The whole-cell model is able to predict viability of M. genitalium cells in response to genetic mutations.[32]

An important milestone in the development of systems biology has become the international project Physiome.

Associated disciplines

According to the interpretation of Systems Biology as the ability to obtain, integrate and analyze complex data sets from multiple experimental sources using interdisciplinary tools, some typical technology platforms are phenomics, organismal variation in phenotype as it changes during its life span; genomics, organismal deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) sequence, including intra-organismal cell specific variation. (i.e., telomere length variation); epigenomics/epigenetics, organismal and corresponding cell specific transcriptomic regulating factors not empirically coded in the genomic sequence. (i.e., DNA methylation, Histone acetylation and deacetylation, etc.); transcriptomics, organismal, tissue or whole cell gene expression measurements by DNA microarrays or serial analysis of gene expression; interferomics, organismal, tissue, or cell-level transcript correcting factors (i.e., RNA interference), proteomics, organismal, tissue, or cell level measurements of proteins and peptides via two-dimensional gel electrophoresis, mass spectrometry or multi-dimensional protein identification techniques (advanced HPLC systems coupled with mass spectrometry). Sub disciplines include phosphoproteomics, glycoproteomics and other methods to detect chemically modified proteins; metabolomics, measurements of small molecules known as metabolites in the system at the organismal, cell, or tissue level;[33] glycomics, organismal, tissue, or cell-level measurements of carbohydrates; lipidomics, organismal, tissue, or cell level measurements of lipids.

In addition to the identification and quantification of the above given molecules further techniques analyze the dynamics and interactions within a cell.The interactions studied include organismal, tissue, cell, and molecular interactions within the cell (interactomics).[34] Currently, the authoritative molecular discipline in this field of study is protein-protein interactions (PPI), although the working definition does not preclude inclusion of other molecular disciplines. These molecular disciplines include; neuroelectrodynamics, an organismal network where the brain's computing function as a dynamic system includes underlying biophysical mechanisms and emerging computation by electrical interactions;[35] fluxomics, measurements of molecular dynamic changes over time in a system such as a cell, tissue, or organism;[33] biomics, systems analysis of the biome; and molecular biokinematics, the study of "biology in motion" focused on how cells transit between steady states such as in proteins molecular mechanism.[36]

In approaching a systems biology problem there are two main approaches. These are the top down and bottom up approach. The top down approach takes as much of the system into account as possible and relies largely on experimental results. The RNA-seq technique is an example of an experimental top down approach. Conversely, the bottom up approach is used to create detailed models while also incorporating experimental data. An example of the bottom up approach is the use of circuit models to describe a simple gene network.[37]

Various technologies utilized to capture dynamic changes in mRNA, proteins, and post-translational modifications. Mechanobiology, forces and physical properties at all scales, their interplay with other regulatory mechanisms;[38] biosemiotics, analysis of the system of sign relations of an organism or other biosystems; Physiomics, a systematic study of physiome in biology.

Cancer systems biology is an example of the systems biology approach, which can be distinguished by the specific object of study (tumorigenesis and treatment of cancer). It works with the specific data (patient samples, high-throughput data with particular attention to characterizing cancer genome in patient tumour samples) and tools (immortalized cancer cell lines, mouse models of tumorigenesis, xenograft models, high-throughput sequencing methods, siRNA-based gene knocking down high-throughput screenings, computational modeling of the consequences of somatic mutations and genome instability).[39] The long-term objective of the systems biology of cancer is ability to better diagnose cancer, classify it and better predict the outcome of a suggested treatment, which is a basis for personalized cancer medicine and virtual cancer patient in more distant prospective. Significant efforts in computational systems biology of cancer have been made in creating realistic multi-scale in silico models of various tumours.[40]

The investigations are frequently combined with large-scale perturbation methods, including gene-based (RNAi, mis-expression of wild type and mutant genes) and chemical approaches using small molecule libraries. Robots and automated sensors enable such large-scale experimentation and data acquisition. These technologies are still emerging and many face problems that the larger the quantity of data produced, the lower the quality. A wide variety of quantitative scientists (computational biologists, statisticians, mathematicians, computer scientists and physicists) are working to improve the quality of these approaches and to create, refine, and retest the models to accurately reflect observations.

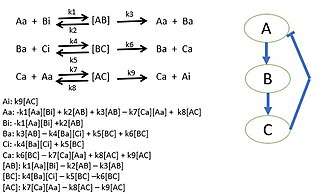

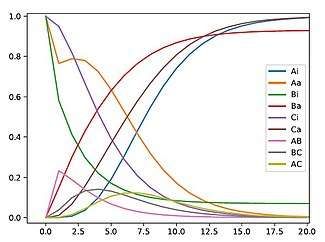

The systems biology approach often involves the development of mechanistic models, such as the reconstruction of dynamic systems from the quantitative properties of their elementary building blocks.[41][42][43][44] For instance, a cellular network can be modelled mathematically using methods coming from chemical kinetics[45] and control theory. Due to the large number of parameters, variables and constraints in cellular networks, numerical and computational techniques are often used (e.g., flux balance analysis).[43][45]

Bioinformatics and data analysis

Other aspects of computer science, informatics, and statistics are also used in systems biology. These include new forms of computational models, such as the use of process calculi to model biological processes (notable approaches include stochastic π-calculus, BioAmbients, Beta Binders, BioPEPA, and Brane calculus) and constraint-based modeling; integration of information from the literature, using techniques of information extraction and text mining;[46] development of online databases and repositories for sharing data and models, approaches to database integration and software interoperability via loose coupling of software, websites and databases, or commercial suits; network-based approaches for analyzing high dimensional genomic data sets. For example, weighted correlation network analysis is often used for identifying clusters (referred to as modules), modeling the relationship between clusters, calculating fuzzy measures of cluster (module) membership, identifying intramodular hubs, and for studying cluster preservation in other data sets; pathway-based methods for omics data analysis, e.g. approaches to identify and score pathways with differential activity of their gene, protein, or metabolite members.[47] Much of the analysis of genomic data sets also include identifying correlations. Additionally, as much of the information comes from different fields, the development of syntactically and semantically sound ways of representing biological models is needed.[48]

Creating biological models

Researchers begin by choosing a biological pathway and diagramming all of the protein interactions. After determining all of the interactions of the proteins, mass action kinetics is utilized to describe the speed of the reactions in the system. Mass action kinetics will provide differential equations to model the biological system as a mathematical model in which experiments can determine the parameter values to use in the differential equations.[50] These parameter values will be the reaction rates of each proteins interaction in the system. This model determines the behavior of certain proteins in biological systems and bring new insight to the specific activities of individual proteins. Sometimes it is not possible to gather all reaction rates of a system. Unknown reaction rates are determined by simulating the model of known parameters and target behavior which provides possible parameter values.[51][49]

See also

- Biological computation

- Computational biology

- Exposome

- Interactome

- List of omics topics in biology

- Metabolic network modelling

- Modelling biological systems

- Molecular pathological epidemiology

- Network biology

- Network medicine

- Noogenesis – Emergence and evolution of intelligence

- Synthetic biology

- Systems biomedicine

- Systems immunology

References

- Tavassoly, Iman; Goldfarb, Joseph; Iyengar, Ravi (2018-10-04). "Systems biology primer: the basic methods and approaches". Essays in Biochemistry. 62 (4): 487–500. doi:10.1042/EBC20180003. ISSN 0071-1365. PMID 30287586.

- Zewail, Ahmed (2008). Physical Biology: From Atoms to Medicine. Imperial College Press. p. 339.

- Longo, Giuseppe; Montévil, Maël (2014). Perspectives on Organisms - Springer. Lecture Notes in Morphogenesis. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-35938-5. ISBN 978-3-642-35937-8.

- Bu Z, Callaway DJ (2011). "Proteins MOVE! Protein dynamics and long-range allostery in cell signaling". Protein Structure and Diseases. Advances in Protein Chemistry and Structural Biology. 83. pp. 163–221. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-381262-9.00005-7. ISBN 978-0-123-81262-9. PMID 21570668.

- Snoep, Jacky L; Westerhoff, Hans V (2005). "From isolation to integration, a systems biology approach for building the Silicon Cell". In Alberghina, Lilia; Westerhoff, Hans V (eds.). Systems Biology: Definitions and Perspectives. Topics in Current Genetics. 13. Berlin: Springer-Verlag. pp. 13–30. doi:10.1007/b106456. ISBN 978-3-540-22968-1.

- "Systems Biology: the 21st Century Science". Institute for Systems Biology. Retrieved 15 June 2011.

- Noble, Denis (2006). The music of life: Biology beyond the genome. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 176. ISBN 978-0-19-929573-9.

- Sauer, Uwe; Heinemann, Matthias; Zamboni, Nicola (27 April 2007). "Genetics: Getting Closer to the Whole Picture". Science. 316 (5824): 550–551. doi:10.1126/science.1142502. PMID 17463274.

- Kholodenko, Boris N; Sauro, Herbert M (2005). "Mechanistic and modular approaches to modeling and inference of cellular regulatory networks". In Alberghina, Lilia; Westerhoff, Hans V (eds.). Systems Biology: Definitions and Perspectives. Topics in Current Genetics. 13. Berlin: Springer-Verlag. pp. 357–451. doi:10.1007/b136809. ISBN 978-3-540-22968-1.

- Chiara Romualdi; Gerolamo Lanfranchi (2009). "Statistical Tools for Gene Expression Analysis and Systems Biology and Related Web Resources". In Stephen Krawetz (ed.). Bioinformatics for Systems Biology (2nd ed.). Humana Press. pp. 181–205. doi:10.1007/978-1-59745-440-7_11. ISBN 978-1-59745-440-7.

- Voit, Eberhard (2012). A First Course in Systems Biology. Garland Science. ISBN 9780815344674.

- Baitaluk, M. (2009). "System Biology of Gene Regulation". Biomedical Informatics. Methods in Molecular Biology. 569. pp. 55–87. doi:10.1007/978-1-59745-524-4_4. ISBN 978-1-934115-63-3. PMID 19623486.

- von Bertalanffy, Ludwig (28 March 1976) [1968]. General System theory: Foundations, Development, Applications. George Braziller. p. 295. ISBN 978-0-8076-0453-3.

- Hodgkin, Alan L; Huxley, Andrew F (28 August 1952). "A quantitative description of membrane current and its application to conduction and excitation in nerve". Journal of Physiology. 117 (4): 500–544. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.1952.sp004764. PMC 1392413. PMID 12991237.

- Le Novère, Nicolas (13 June 2007). "The long journey to a Systems Biology of neuronal function". BMC Systems Biology. 1: 28. doi:10.1186/1752-0509-1-28. PMC 1904462. PMID 17567903.

- Turing, A. M. (1952). "The Chemical Basis of Morphogenesis" (PDF). Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 237 (641): 37–72. Bibcode:1952RSPTB.237...37T. doi:10.1098/rstb.1952.0012. JSTOR 92463.

- Noble, Denis (5 November 1960). "Cardiac action and pacemaker potentials based on the Hodgkin-Huxley equations". Nature. 188 (4749): 495–497. Bibcode:1960Natur.188..495N. doi:10.1038/188495b0. PMID 13729365.

- Mesarovic, Mihajlo D. (1968). Systems Theory and Biology. Berlin: Springer-Verlag.

- Rosen, Robert (5 July 1968). "A Means Toward a New Holism". Science. 161 (3836): 34–35. Bibcode:1968Sci...161...34M. doi:10.1126/science.161.3836.34. JSTOR 1724368.

- Hunter, Philip (May 2012). "Back down to Earth: Even if it has not yet lived up to its promises, systems biology has now matured and is about to deliver its first results". EMBO Reports. 13 (5): 408–411. doi:10.1038/embor.2012.49. PMC 3343359. PMID 22491028.

- Zou, Yawen; Laubichler, Manfred D. (2018-07-25). "From systems to biology: A computational analysis of the research articles on systems biology from 1992 to 2013". PLOS One. 13 (7): e0200929. Bibcode:2018PLoSO..1300929Z. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0200929. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 6059489. PMID 30044828.

- B. J. Zeng, "On the holographic model of human body", 1st National Conference of Comparative Studies Traditional Chinese Medicine and West Medicine, Medicine and Philosophy, April 1992 ("systems medicine and pharmacology" termed).

- Zeng (B.) J., On the concept of system biological engineering, Communication on Transgenic Animals, No. 6, June, 1994.

- B. J. Zeng, "Transgenic animal expression system – transgenic egg plan (goldegg plan)", Communication on Transgenic Animal, Vol.1, No.11, 1994 (on the concept of system genetics and term coined).

- B. J. Zeng, "From positive to synthetic science", Communication on Transgenic Animals, No. 11, 1995 (on systems medicine).

- B. J. Zeng, "The structure theory of self-organization systems", Communication on Transgenic Animals, No.8-10, 1996. Etc.

- Tomita, Masaru; Hashimoto, Kenta; Takahashi, Kouichi; Shimizu, Thomas S; Matsuzaki, Yuri; Miyoshi, Fumihiko; Saito, Kanako; Tanida, Sakura; et al. (1997). "E-CELL: Software Environment for Whole Cell Simulation". Genome Inform Ser Workshop Genome Inform. 8: 147–155. PMID 11072314. Retrieved 15 June 2011.

- "HMS launches new department to study systems biology". Harvard Gazette. September 23, 2003.

- Ayyadurai, VA; Dewey, CF (March 2011). "CytoSolve: A Scalable Computational Method for Dynamic Integration of Multiple Molecular Pathway Models". Cell Mol Bioeng. 4 (1): 28–45. doi:10.1007/s12195-010-0143-x. PMC 3032229. PMID 21423324.

- "Systems Biology - National Institute of General Medical Sciences". Archived from the original on 19 October 2013. Retrieved 12 December 2012.

- Kling, Jim (3 March 2006). "Working the Systems". Science. Retrieved 15 June 2011.

- Karr, Jonathan R.; Sanghvi, Jayodita C.; Macklin, Derek N.; Gutschow, Miriam V.; Jacobs, Jared M.; Bolival, Benjamin; Assad-Garcia, Nacyra; Glass, John I.; Covert, Markus W. (July 2012). "A Whole-Cell Computational Model Predicts Phenotype from Genotype". Cell. 150 (2): 389–401. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.044. PMC 3413483. PMID 22817898.

- Cascante, Marta; Marin, Silvia (2008-09-30). "Metabolomics and fluxomics approaches". Essays in Biochemistry. 45: 67–82. doi:10.1042/bse0450067. ISSN 0071-1365. PMID 18793124.

- Cusick, Michael E.; Klitgord, Niels; Vidal, Marc; Hill, David E. (2005-10-15). "Interactome: gateway into systems biology". Human Molecular Genetics. 14 (suppl_2): R171–R181. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddi335. ISSN 0964-6906. PMID 16162640.

- Aur, Dorian (2012). "From Neuroelectrodynamics to Thinking Machines". Cognitive Computation. 4 (1): 4–12. doi:10.1007/s12559-011-9106-3. ISSN 1866-9956.

- Diez, Mikel; Petuya, Víctor; Martínez-Cruz, Luis Alfonso; Hernández, Alfonso (2011-12-01). "A biokinematic approach for the computational simulation of proteins molecular mechanism". Mechanism and Machine Theory. 46 (12): 1854–1868. doi:10.1016/j.mechmachtheory.2011.07.013. ISSN 0094-114X.

- Loor, Khuram Shahzad and Juan J. (2012-07-31). "Application of Top-Down and Bottom-up Systems Approaches in Ruminant Physiology and Metabolism". Current Genomics. 13 (5): 379–394. doi:10.2174/138920212801619269. PMC 3401895. PMID 23372424.

- Spill, Fabian; Bakal, Chris; Mak, Michael (2018). "Mechanical and Systems Biology of Cancer". Computational and Structural Biotechnology Journal. 16: 237–245. arXiv:1807.08990. Bibcode:2018arXiv180708990S. doi:10.1016/j.csbj.2018.07.002. PMC 6077126. PMID 30105089.

- Barillot, Emmanuel; Calzone, Laurence; Hupe, Philippe; Vert, Jean-Philippe; Zinovyev, Andrei (2012). Computational Systems Biology of Cancer. Chapman & Hall/CRCMathematical & Computational Biology. p. 461. ISBN 978-1439831441.

- Byrne, Helen M. (2010). "Dissecting cancer through mathematics: from the cell to the animal model". Nature Reviews Cancer. 10 (3): 221–230. doi:10.1038/nrc2808. PMID 20179714.

- Gardner, Timothy .S; di Bernardo, Diego; Lorenz, David; Collins, James J. (4 July 2003). "Inferring Genetic Networks and Identifying Compound Mode of Action via Expression Profiling". Science. 301 (5629): 102–105. Bibcode:2003Sci...301..102G. doi:10.1126/science.1081900. PMID 12843395.

- di Bernardo, Diego; Thompson, Michael J.; Gardner, Timothy S.; Chobot, Sarah E.; Eastwood, Erin L.; Wojtovich, Andrew P.; Elliott, Sean J.; Schaus, Scott E.; Collins, James J. (March 2005). "Chemogenomic profiling on a genome-wide scale using reverse-engineered gene networks". Nature Biotechnology. 23 (3): 377–383. doi:10.1038/nbt1075. PMID 15765094.

- Tavassoly, Iman (2015). Dynamics of Cell Fate Decision Mediated by the Interplay of Autophagy and Apoptosis in Cancer Cells. Springer Theses. Springer International Publishing. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-14962-2. ISBN 978-3-319-14961-5.

- Korkut, A; Wang, W; Demir, E; Aksoy, BA; Jing, X; Molinelli, EJ; Babur, Ö; Bemis, DL; Onur Sumer, S; Solit, DB; Pratilas, CA; Sander, C (18 August 2015). "Perturbation biology nominates upstream-downstream drug combinations in RAF inhibitor resistant melanoma cells". eLife. 4. doi:10.7554/eLife.04640. PMC 4539601. PMID 26284497.

- Gupta, Ankur; Rawlings, James B. (April 2014). "Comparison of Parameter Estimation Methods in Stochastic Chemical Kinetic Models: Examples in Systems Biology". AIChE Journal. 60 (4): 1253–1268. doi:10.1002/aic.14409. ISSN 0001-1541. PMC 4946376. PMID 27429455.

- Ananadou, Sophia; Kell, Douglas; Tsujii, Jun-ichi (December 2006). "Text mining and its potential applications in systems biology". Trends in Biotechnology. 24 (12): 571–579. doi:10.1016/j.tibtech.2006.10.002. PMID 17045684.

- Glaab, Enrico; Schneider, Reinhard (2012). "PathVar: analysis of gene and protein expression variance in cellular pathways using microarray data". Bioinformatics. 28 (3): 446–447. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btr656. PMC 3268235. PMID 22123829.

- Bardini, R.; Politano, G.; Benso, A.; Di Carlo, S. (2017-01-01). "Multi-level and hybrid modelling approaches for systems biology". Computational and Structural Biotechnology Journal. 15: 396–402. doi:10.1016/j.csbj.2017.07.005. ISSN 2001-0370. PMC 5565741. PMID 28855977.

- Transtrum, Mark K.; Qiu, Peng (2016-05-17). "Bridging Mechanistic and Phenomenological Models of Complex Biological Systems". PLOS Computational Biology. 12 (5): e1004915. arXiv:1509.06278. Bibcode:2016PLSCB..12E4915T. doi:10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004915. ISSN 1553-7358. PMC 4871498. PMID 27187545.

- Chellaboina, V.; Bhat, S. P.; Haddad, W. M.; Bernstein, D. S. (August 2009). "Modeling and analysis of mass-action kinetics". IEEE Control Systems Magazine. 29 (4): 60–78. doi:10.1109/MCS.2009.932926. ISSN 1941-000X.

- Brown, Kevin S.; Sethna, James P. (2003-08-12). "Statistical mechanical approaches to models with many poorly known parameters". Physical Review E. 68 (2): 021904. Bibcode:2003PhRvE..68b1904B. doi:10.1103/physreve.68.021904. ISSN 1063-651X. PMID 14525003.

Further reading

- Klipp, Edda; Liebermeister, Wolfram; Wierling, Christoph; Kowald, Axel (2016). Systems Biology - A Textbook, 2nd edition. Wiley. ISBN 978-3-527-33636-4.

- Asfar S. Azmi, ed. (2012). Systems Biology in Cancer Research and Drug Discovery. ISBN 978-94-007-4819-4.

- Kitano, Hiroaki (15 October 2001). Foundations of Systems Biology. MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-11266-6.

- Werner, Eric (29 March 2007). "All systems go". Nature. 446 (7135): 493–494. Bibcode:2007Natur.446..493W. doi:10.1038/446493a. provides a comparative review of three books:

- Alon, Uri (7 July 2006). An Introduction to Systems Biology: Design Principles of Biological Circuits. Chapman & Hall. ISBN 978-1-58488-642-6.

- Kaneko, Kunihiko (15 September 2006). Life: An Introduction to Complex Systems Biology. Springer-Verlag. Bibcode:2006lics.book.....K. ISBN 978-3-540-32666-3.

- Palsson, Bernhard O. (16 January 2006). Systems Biology: Properties of Reconstructed Networks. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-85903-5.

- Werner Dubitzky; Olaf Wolkenhauer; Hiroki Yokota; Kwan-Hyun Cho, eds. (13 August 2013). Encyclopedia of Systems Biology. Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-1-4419-9864-4.