Rama

Rama or Ram (/ˈrɑːmə/;[2] Sanskrit: राम, IAST: Rāma, Sanskrit pronunciation: [ˈraːmɐ] (![]()

| Rama (Ramachandra) | |

|---|---|

Rama is a Hindu deity, his iconography varies | |

| Affiliation | Seventh avatar of Vishnu, Brahman (Vaishnavism), Deva |

| Predecessor | Dasharatha |

| Abode | Vaikuntha, Ayodhya, and Saket |

| Weapon | Bow and arrows |

| Texts | Ramayana and its other versions |

| Festivals | Rama Navami, Vivaha Panchami, Deepavali, Dusshera |

| Personal information | |

| Born | |

| Parents | Dasharatha (father)[1] Kaushalya (mother)[1] Kaikeyi (step-mother) Sumitra (step-mother) |

| Siblings | Shanta (sister) Lakshmana (half-brother) Bharata (half-brother) Shatrughna (half-brother) |

| Consort | Sita[1] |

| Children | Lava (son) Kusha (son) |

| Dynasty | Raghuvanshi-Ikshvaku-Suryavanshi |

| Part of a series on |

| Vaishnavism |

|---|

|

|

Holy scriptures

|

|

Sampradayas

|

|

Related traditions |

|

|

Rama was born to Kaushalya and Dasharatha in Ayodhya, the ruler of the Kingdom of Kosala. His siblings included Lakshmana, Bharata, and Shatrughna. He married Sita. Though born in a royal family, their life is described in the Hindu texts as one challenged by unexpected changes such as an exile into impoverished and difficult circumstances, ethical questions and moral dilemmas.[7] Of all their travails, the most notable is the kidnapping of Sita by demon-king Ravana, followed by the determined and epic efforts of Rama and Lakshmana to gain her freedom and destroy the evil Ravana against great odds. The entire life story of Rama, Sita and their companions allegorically discusses duties, rights and social responsibilities of an individual. It illustrates dharma and dharmic living through model characters.[7][8]

Rama is especially important to Vaishnavism. He is the central figure of the ancient Hindu epic Ramayana, a text historically popular in the South Asian and Southeast Asian cultures.[9][10][11] His ancient legends have attracted bhasya (commentaries) and extensive secondary literature and inspired performance arts. Two such texts, for example, are the Adhyatma Ramayana – a spiritual and theological treatise considered foundational by Ramanandi monasteries,[12] and the Ramcharitmanas – a popular treatise that inspires thousands of Ramlila festival performances during autumn every year in India.[13][14][15]

Rama legends are also found in the texts of Jainism and Buddhism, though he is sometimes called Pauma or Padma in these texts,[16] and their details vary significantly from the Hindu versions.[17]

Etymology and nomenclature

Rāma is a Vedic Sanskrit word with two contextual meanings. In one context as found in Atharva Veda, as stated by Monier Monier-Williams, means "dark, dark-colored, black" and is related to the term ratri which means night. In another context as found in other Vedic texts, the word means "pleasing, delightful, charming, beautiful, lovely".[18][19] The word is sometimes used as a suffix in different Indian languages and religions, such as Pali in Buddhist texts, where -rama adds the sense of "pleasing to the mind, lovely" to the composite word.[20]

Rama as a first name appears in the Vedic literature, associated with two patronymic names – Margaveya and Aupatasvini – representing different individuals. A third individual named Rama Jamadagnya is the purported author of hymn 10.110 of the Rigveda in the Hindu tradition.[18] The word Rama appears in ancient literature in reverential terms for three individuals:[18]

- Parashu-rama, as the sixth avatar of Vishnu. He is linked to the Rama Jamadagnya of the Rigveda fame.

- Rama-chandra, as the seventh avatar of Vishnu and of the ancient Ramayana fame.

- Bala-rama, also called Halayudha, as the elder brother of Krishna both of whom appear in the legends of Hinduism, Buddhism and Jainism.

The name Rama appears repeatedly in Hindu texts, for many different scholars and kings in mythical stories.[18] The word also appears in ancient Upanishads and Aranyakas layer of Vedic literature, as well as music and other post-Vedic literature, but in qualifying context of something or someone who is "charming, beautiful, lovely" or "darkness, night".[18]

The Vishnu avatar named Rama is also known by other names. He is called Ramachandra (beautiful, lovely moon[19]), or Dasarathi (son of Dasaratha), or Raghava (descendant of Raghu, solar dynasty in Hindu cosmology).[18][21] He is also known as Ram Lalla ( Infant form of Rama).[22]

Additional names of Rama include Ramavijaya (Javanese), Phreah Ream (Khmer), Phra Ram (Lao and Thai), Megat Seri Rama (Malay), Raja Bantugan (Maranao), Ramudu (Telugu), Ramar (Tamil).[23] In the Vishnu sahasranama, Rama is the 394th name of Vishnu. In some Advaita Vedanta inspired texts, Rama connotes the metaphysical concept of Supreme Brahman who is the eternally blissful spiritual Self (Atman, soul) in whom yogis delight nondualistically.[12]

The root of the word Rama is ram- which means "stop, stand still, rest, rejoice, be pleased".[19]

According to Douglas Q. Adams, the Sanskrit word Rama is also found in other Indo-European languages such as Tocharian ram, reme, *romo- where it means "support, make still", "witness, make evident".[19][24] The sense of "dark, black, soot" also appears in other Indo European languages, such as *remos or Old English romig.[25][note 1]

Legends

This summary is a traditional legendary account, based on literary details from the Ramayana and other historic mythology-containing texts of Buddhism and Jainism. According to Sheldon Pollock, the figure of Rama incorporates more ancient "morphemes of Indian myths", such as the mythical legends of Bali and Namuci. The ancient sage Valmiki used these morphemes in his Ramayana similes as in sections 3.27, 3.59, 3.73, 5.19 and 29.28.[27]

Birth

Rama was born on the ninth day of the lunar month Chaitra (March–April), a day celebrated across India as Ram Navami. This coincides with one of the four Navratri on the Hindu calendar, in the spring season, namely the Vasantha Navratri.[28]

The ancient epic Ramayana states in the Balakhanda that Rama and his brothers were born to Kaushalya and Dasharatha in Ayodhya, a city on the banks of Sarayu River.[29][30] The Jain versions of the Ramayana, such as the Paumacariya (literally deeds of Padma) by Vimalasuri, also mention the details of the early life of Rama. The Jain texts are dated variously, but generally pre-500 CE, most likely sometime within the first five centuries of the common era.[31] Moriz Winternitz states that the Valmiki Ramayana was already famous before it was recast in the Jain Paumacariya poem, dated to the second-half of the 1st century, which pre-dates a similar retelling found in the Buddha-carita of Asvagosa, dated to the beginning of the 2nd century or prior.[32]

Dasharatha was the king of Kosala, and a part of the solar dynasty of Iksvakus. His mother's name Kaushalya literally implies that she was from Kosala. The kingdom of Kosala is also mentioned in Buddhist and Jaina texts, as one of the sixteen Maha janapadas of ancient India, and as an important center of pilgrimage for Jains and Buddhists.[29][33] However, there is a scholarly dispute whether the modern Ayodhya is indeed the same as the Ayodhya and Kosala mentioned in the Ramayana and other ancient Indian texts.[34][note 2]

Youth, family and friends

Rama had three brothers, according to the Balakhanda section of the Ramayana. These were Lakshmana, Bharata and Shatrughna.[1] The extant manuscripts of the text describes their education and training as young princes, but this is brief. Rama is portrayed as a polite, self-controlled, virtuous youth always ready to help others. His education included the Vedas, the Vedangas as well as the martial arts.[37]

The years when Rama grew up are described in much greater detail by later Hindu texts, such as the Ramavali by Tulsidas. The template is similar to those found for Krishna, but in the poems of Tulsidas, Rama is milder and reserved introvert, rather than the prank-playing extrovert personality of Krishna.[1]

The Ramayana mentions an archery contest organised by King Janaka, where Sita and Rama meet. Rama wins the contest, whereby Janaka agrees to the marriage of Sita and Rama. Sita moves with Rama to his father Dashratha's capital.[1] Sita introduces Rama's brothers to her sister and her two cousins, and they all get married.[37]

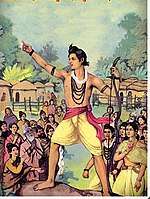

While Rama and his brothers were away, Kaikeyi, the mother of Bharata and the second wife of King Dasharatha, reminds the king that he had promised long ago to comply with one thing she asks, anything. Dasharatha remembers and agrees to do so. She demands that Rama be exiled for fourteen years to Dandaka forest.[37] Dasharatha grieves at her request. Her son Bharata, and other family members become upset at her demand. Rama states that his father should keep his word, adds that he does not crave for earthly or heavenly material pleasures, neither seeks power nor anything else. He talks about his decision with his wife and tells everyone that time passes quickly. Sita leaves with him to live in the forest, the brother Lakshmana joins them in their exile as the caring close brother.[37]

Exile and war

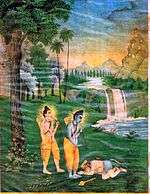

Rama in Forest

Rama in Forest Ravana's sister Suparnakha attempts to seduce Rama and cheat on Sita. He refuses and spurns her (above).

Ravana's sister Suparnakha attempts to seduce Rama and cheat on Sita. He refuses and spurns her (above).

Hanuman meets Shri Rama in the forest.

Hanuman meets Shri Rama in the forest.

Rama heads outside the Kosala kingdom, crosses Yamuna river and initially stays at Chitrakuta, on the banks of river Mandakini, in the hermitage of sage Vasishtha.[38] This place is believed in the Hindu tradition to be the same as Chitrakoot on the border of Uttar Pradesh and Madhya Pradesh. The region has numerous Rama temples and is an important Vaishnava pilgrimage site.[38] The texts describe nearby hermitages of Vedic rishis (sages) such as Atri, and that Rama roamed through forests, lived a humble simple life, provided protection and relief to ascetics in the forest being harassed and persecuted by demons, as they stayed at different ashrams.[38][39]

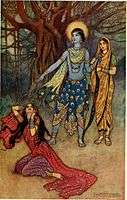

After ten years of wandering and struggles, Rama arrives at Panchavati, on the banks of river Godavari. This region had numerous demons (rakshashas). One day, a demoness called Shurpanakha saw Rama, became enamored of him, and tried to seduce him.[37] Rama refused her. Shurpanakha retaliated by threatening Sita. Lakshmana, the younger brother protective of his family, in turn retaliated by cutting off the nose and ears of Shurpanakha. The cycle of violence escalated, ultimately reaching demon king Ravana, who was the brother of Shurpanakha. Ravana comes to Panchavati to take revenge on behalf of his family, sees Sita, gets attracted, and kidnaps Sita to his kingdom of Lanka (believed to be modern Sri Lanka).[37][39]

Rama and Lakshmana discover the kidnapping, worry about Sita's safety, despair at the loss and their lack of resources to take on Ravana. Their struggles now reach new heights. They travel south, meet Sugriva, marshall an army of monkeys, and attract dedicated commanders such as Hanuman who is a minister of Sugriva.[40] Meanwhile, Ravana harasses Sita and tries to make her into a concubine. Sita refuses him. Ravana is enraged. Rama ultimately reaches Lanka, fights in a war that has many ups and downs, but ultimately Rama prevails, kills Ravana and forces of evil, and rescues his wife Sita. They return to Ayodhya.[37][41]

Post-war rule and death

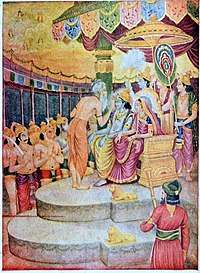

.jpg)

The return of Rama to Ayodhya is celebrated with his coronation. It is called Rama pattabhisheka, and his rule itself as Rama rajya described to be a just and fair rule.[42][43] It is believed by many that when Rama returned people celebrated their happiness with fireworks, and the festival of Diwali is connected with Rama's return.

Upon Rama's accession as king, rumours emerge that Sita may have gone willingly when she was with Ravana; Sita protests that her capture was forced. Rama responds to public gossip by renouncing his wife, and asking her to undergo a test before Agni (fire). She does, and passes the test. Rama and Sita live happily together in Ayodhya, have twin sons named Luv and Kush, in the Ramayana and other major texts.[39] However, in some revisions, the story is different and tragic, with Sita dying of sorrow for her husband not trusting her, making Sita a moral heroine and leaving the reader with moral questions about Rama.[44][45] In these revisions, the death of Sita leads Rama to drown himself. Through death, he joins her in afterlife.[46] Rama dying by drowning himself is found in the Myanmar version of Rama's life story called Thiri Rama.[47]

Inconsistencies

Rama's legends vary significantly by the region and across manuscripts. While there is a common foundation, plot, grammar and an essential core of values associated with a battle between good and evil, there is neither a correct version nor a single verifiable ancient one. According to Paula Richman, there are hundreds of versions of "the story of Rama in India, southeast Asia and beyond".[48][49] The versions vary by region reflecting local preoccupations and histories, and these cannot be called "divergences or different tellings" from the "real" version, rather all the versions of Rama story are real and true in their own meanings to the local cultural tradition, according to scholars such as Richman and Ramanujan.[48]

The stories vary in details, particularly where the moral question is clear, but the appropriate ethical response is unclear or disputed.[50][51] For example, when demoness Shurpanakha disguises as a woman to seduce Rama, then stalks and harasses Rama's wife Sita after Rama refuses her, Lakshmana is faced with the question of appropriate ethical response. In the Indian tradition, states Richman, the social value is that "a warrior must never harm a woman".[50] The details of the response by Rama and Lakshmana, and justifications for it, has numerous versions. Similarly, there are numerous and very different versions to how Rama deals with rumours against Sita when they return victorious to Ayodhya, given that the rumours can neither be objectively investigated nor summarily ignored.[52] Similarly the versions vary on many other specific situations and closure such as how Rama, Sita and Lakshmana die.[50][53]

The variation and inconsistencies are not limited to the texts found in the Hinduism traditions. The Rama story in the Jainism tradition also show variation by author and region, in details, in implied ethical prescriptions and even in names – the older versions using the name Padma instead of Rama, while the later Jain texts just use Rama.[54]

Dating

In some Hindu texts, Rama is stated to have lived in the Treta yuga or Dvapar yuga that their authors estimate existed before about 5,000 BCE. A few other researchers place Rama to have more plausibly lived around 1250 BCE,[56] based on regnal lists of Kuru and Vrishni leaders which if given more realistic reign lengths would place Bharat and Satwata, contemporaries of Rama, around that period. According to Hasmukh Dhirajlal Sankalia, an Indian archaeologist, who specialised in Proto- and Ancient Indian history, this is all "pure speculation".[57]

The composition of Rama's epic story, the Ramayana, in its current form is usually dated between 7th and 4th century BCE.[58][59] According to John Brockington, a professor of Sanskrit at Oxford known for his publications on the Ramayana, the original text was likely composed and transmitted orally in more ancient times, and modern scholars have suggested various centuries in the 1st millennium BCE. In Brockington's view, "based on the language, style and content of the work, a date of roughly the fifth century BCE is the most reasonable estimate".[60]

.jpg)

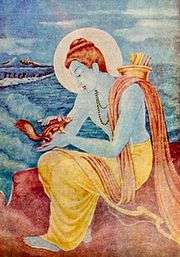

Appearance

Valmiki in Ramayana describes Rama as a charming, well built person of a dark complexion (varnam shyaamam) and long arms (Aajana bahu). In the Sundara Kanda section of the epic, Hanuman describes Rama to Sita when she is held captive in Lanka to prove to her that he is indeed a messenger from Rama:

He has broad shoulders, mighty arms, a conch-shaped neck, a charming countenance and coppery eyes;

he has his clavicle concealed and is known by the people as Rama. He has a voice (deep) like the sound of a kettledrum and glossy skin, is full of glory, square-built and of well proportioned limbs

and is endowed with a dark-brown complexion.[61]

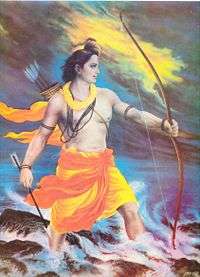

Iconography

Rama iconography shares elements of Vishnu avatars, but has several distinctive elements. It never has more than two hands, he holds (or has nearby) a bana (arrow) in his right hand, while he holds the dhanus (bow) in his left.[62] The most recommended icon for him is that he be shown standing in tribhanga pose (thrice bent "S" shape). He is shown black, blue or dark color, typically wearing reddish color clothes. If his wife and brother are a part of the iconography, Lakshamana is on his left side while Sita always on the right of Rama, both of golden-yellow complexion.[62]

Philosophy and symbolism

Rama's life story is imbued with symbolism. According to Sheldon Pollock, the life of Rama as told in the Indian texts is a masterpiece that offers a framework to represent, conceptualise and comprehend the world and the nature of life. Like major epics and religious stories around the world, it has been of vital relevance because it "tells the culture what it is". Rama's life is more complex than the Western template for the battle between the good and the evil, where there is a clear distinction between immortal powerful gods or heroes and mortal struggling humans. In the Indian traditions, particularly Rama, the story is about a divine human, a mortal god, incorporating both into the exemplar who transcends both humans and gods.[63]

A superior being does not render evil for evil,

this is the maxim one should observe;

the ornament of virtuous persons is their conduct.

(...)

A noble soul will ever exercise compassion

even towards those who enjoy injuring others.

—Ramayana 6.115, Valmiki

(Abridged, Translator: Roderick Hindery)[64]

As a person, Rama personifies the characteristics of an ideal person (purushottama).[45] He had within him all the desirable virtues that any individual would seek to aspire, and he fulfils all his moral obligations. Rama is considered a maryada purushottama or the best of upholders of Dharma.[65]

According to Rodrick Hindery, Book 2, 6 and 7 are notable for ethical studies.[66][51] The views of Rama combine "reason with emotions" to create a "thinking hearts" approach. Second, he emphasises through what he says and what he does a union of "self-consciousness and action" to create an "ethics of character". Third, Rama's life combines the ethics with the aesthetics of living.[66] The story of Rama and people in his life raises questions such as "is it appropriate to use evil to respond to evil?", and then provides a spectrum of views within the framework of Indian beliefs such as on karma and dharma.[64]

Rama's life and comments emphasise that one must pursue and live life fully, that all three life aims are equally important: virtue (dharma), desires (kama), and legitimate acquisition of wealth (artha). Rama also adds, such as in section 4.38 of the Ramayana, that one must also introspect and never neglect what one's proper duties, appropriate responsibilities, true interests, and legitimate pleasures are.[36]

Literary sources

Ramayana

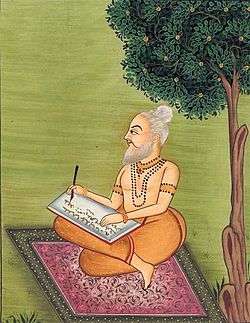

The primary source of the life of Rama is the Sanskrit epic Ramayana composed by Rishi Valmiki.

The epic had many versions across India's regions. The followers of Madhvacharya believe that an older version of the Ramayana, the Mula-Ramayana, previously existed. The Madhva tradition considers it to have been more authoritative than the version by Valmiki.

Versions of the Ramayana exist in most major Indian languages; examples that elaborate on the life, deeds and divine philosophies of Rama include the epic poem Ramavataram, and the following vernacular versions of Rama's life story:[67]

- Ramavataram or Kamba-Ramayanam in Tamil by the poet Kambar in Tamil (12th century)

- Saptakanda Ramayana in Assamese by poet Madhava Kandali (14th century)

- Krittivasi Ramayan in Bengali by poet Krittibas Ojha (15th century)

- Ramcharitmanas in Hindi by sant Tulsidas (16th-century)

- Pampa Ramayana, Torave Ramayana by Kumara Valmiki and Sri Ramayana Darshanam by Kuvempu in Kannada;

- Ramayana Kalpavruksham by Viswanatha Satyanarayana and Ramayana by Ranganatha in Telugu;

- Vilanka Ramayana in Odia;

- Eluttachan in Malayalam (this text is closer to the Advaita Vedanta-inspired rendition Adhyatma Ramayana).[68]

The epic is found across India, in different languages and cultural traditions.[69]

Adhyatma Ramayana

Adhyatma Ramayana is a late medieval Sanskrit text extolling the spiritualism in the story of Ramayana. It is embedded in the latter portion of Brahmānda Purana, and constitutes about a third of it.[70] The text philosophically attempts to reconcile Bhakti in god Rama and Shaktism with Advaita Vedanta, over 65 chapters and 4,500 verses.[71][72]

The text represents Rama as the Brahman (metaphysical reality), mapping all attributes and aspects of Rama to abstract virtues and spiritual ideals.[72] Adhyatma Ramayana transposes Ramayana into symbolism of self study of one's own soul, with metaphors described in Advaita terminology.[72] The text is notable because it influenced the popular Ramcharitmanas by Tulsidas,[70][72] and inspired the most popular version of Nepali Ramayana by Bhanubhakta Acharya.[73] This was also translated by Thunchath Ezhuthachan to Malayalam, which lead the foundation of the language itself.

Ramacharitmanas

The Ramayana is a Sanskrit text, while Ramacharitamanasa retells the Ramayana in a vernacular dialect of Hindi language,[74] commonly understood in northern India.[75][76][77] Ramacharitamanasa was composed in the 16th century by Tulsidas.[78][79][74] The popular text is notable for synthesising the epic story in a Bhakti movement framework, wherein the original legends and ideas morph in an expression of spiritual bhakti (devotional love) for a personal god.[74][80][note 3]

Tulsidas was inspired by Adhyatma Ramayana, where Rama and other characters of the Valmiki Ramayana along with their attributes (saguna narrative) were transposed into spiritual terms and abstract rendering of an Atma (soul, self, Brahman) without attributes (nirguna reality).[70][72][82] According to Kapoor, Rama's life story in the Ramacharitamanasa combines mythology, philosophy, and religious beliefs into a story of life, a code of ethics, a treatise on universal human values.[83] It debates in its dialogues the human dilemmas, the ideal standards of behaviour, duties to those one loves, and mutual responsibilities. It inspires the audience to view their own lives from a spiritual plane, encouraging the virtuous to keep going, and comforting those oppressed with a healing balm.[83]

The Ramacharitmanas is notable for being the Rama-based play commonly performed every year in autumn, during the weeklong performance arts festival of Ramlila.[15] The "staging of the Ramayana based on the Ramacharitmanas" was inscribed in 2008 by UNESCO as one of the Intangible Cultural Heritages of Humanity.[84]

Yoga Vasistha

— Yoga Vasistha (Vasistha teaching Rama)

Tr: Christopher Chapple[85]

Yoga Vasistha is a Sanskrit text structured as a conversation between young Prince Rama and sage Vasistha who was called as the first sage of the Vedanta school of Hindu philosophy by Adi Shankara.[86] The complete text contains over 29,000 verses.[86] The short version of the text is called Laghu Yogavasistha and contains 6,000 verses.[87] The exact century of its completion is unknown, but has been estimated to be somewhere between the 6th century to as late as the 14th century, but it is likely that a version of the text existed in the 1st millennium.[88]

The Yoga Vasistha text consists of six books.[89] The first book presents Rama's frustration with the nature of life, human suffering and disdain for the world.[89] The second describes, through the character of Rama, the desire for liberation and the nature of those who seek such liberation.[89] The third and fourth books assert that liberation comes through a spiritual life, one that requires self-effort, and present cosmology and metaphysical theories of existence embedded in stories.[89] These two books are known for emphasising free will and human creative power.[89][90] The fifth book discusses meditation and its powers in liberating the individual, while the last book describes the state of an enlightened and blissful Rama.[89][91]

Yoga Vasistha is considered one of the most important texts of the Vedantic philosophy.[92] The text, states David Gordon White, served as a reference on Yoga for medieval era Advaita Vedanta scholars.[93] The Yoga Vasistha, according to White, was one of the popular texts on Yoga that dominated the Indian Yoga culture scene before the 12th century.[93]

Other texts

Other important historic Hindu texts on Rama include Bhusundi Ramanaya, Prasanna raghava, and Ramavali by Tulsidas.[1][94] The Sanskrit poem Bhaṭṭikāvya of Bhatti, who lived in Gujarat in the seventh century CE, is a retelling of the epic that simultaneously illustrates the grammatical examples for Pāṇini's Aṣṭādhyāyī as well as the major figures of speech and the Prakrit language.[95]

Another historically and chronologically important text is Raghuvamsa authored by Kalidasa.[96] Its story confirms many details of the Ramayana, but has novel and different elements. It mentions that Ayodhya was not the capital in the time of Rama's son named Kusha, but that he later returned to it and made it the capital again. This text is notable because the poetry in the text is exquisite and called a Mahakavya in the Indian tradition, and has attracted many scholarly commentaries. It is also significant because Kalidasa has been dated to between the 4th and 5th century CE, suggesting that the Ramayana legend was well established by the time of Kalidasa.[96]

The Mahabharata has a summary of the Ramayana. The Jainism tradition has extensive literature of Rama as well, but generally refers to him as Padma, such as in the Paumacariya by Vimalasuri.[31] Rama and Sita legend is mentioned in the Jataka tales of Buddhism, as Dasaratha-Jataka (Tale no. 461), but with slightly different spellings such as Lakkhana for Lakshmana and Rama-pandita for Rama.[97][98][99]

The chapter 4 of Vishnu Purana, chapter 112 of Padma Purana, chapter 143 of Garuda Purana and chapters 5 through 11 of Agni Purana also summarise the life story of Rama.[100] Additionally, the Rama story is included in the Vana Parva of the Mahabharata, which has been a part of evidence that the Ramayana is likely more ancient, and it was summarised in the Mahabharata epic in ancient times.[101]

Influence

Rama's story has had a major socio-cultural and inspirational influence across South Asia and Southeast Asia.[9][102]

Few works of literature produced in any place at any time have been as popular, influential, imitated and successful as the great and ancient Sanskrit epic poem, the Valmiki Ramayana.

- – Robert Goldman, Professor of Sanskrit, University of California at Berkeley[9]

According to Arthur Anthony Macdonell, a professor at Oxford and Boden scholar of Sanskrit, Rama's ideas as told in the Indian texts are secular in origin, their influence on the life and thought of people having been profound over at least two and a half millennia.[103][104] Their influence has ranged from being a framework for personal introspection to cultural festivals and community entertainment.[9] His life stories, states Goldman, have inspired "painting, film, sculpture, puppet shows, shadow plays, novels, poems, TV serials and plays".[103]

Hinduism

Rama Navami

Rama Navami is a spring festival that celebrates the birthday of Rama. The festival is a part of the spring Navratri, and falls on the ninth day of the bright half of Chaitra month in the traditional Hindu calendar. This typically occurs in the Gregorian months of March or April every year.[105][106]

The day is marked by recital of Rama legends in temples, or reading of Rama stories at home. Some Vaishnava Hindus visit a temple, others pray within their home, and some participate in a bhajan or kirtan with music as a part of puja and aarti.[107] The community organises charitable events and volunteer meals. The festival is an occasion for moral reflection for many Hindus.[108][109] Some mark this day by vrata (fasting) or a visit to a river for a dip.[108][110][111]

The important celebrations on this day take place at Ayodhya, Sitamarhi,[112] Janakpurdham (Nepal), Bhadrachalam, Kodandarama Temple, Vontimitta and Rameswaram. Rathayatras, the chariot processions, also known as Shobha yatras of Rama, Sita, his brother Lakshmana and Hanuman, are taken out at several places.[108][113][114] In Ayodhya, many take a dip in the sacred river Sarayu and then visit the Rama temple.[111]

Rama Navami day also marks the end of the nine-day spring festival celebrated in Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh called Vasanthothsavam (Festival of Spring), that starts with Ugadi. Some highlights of this day are Kalyanam (ceremonial wedding performed by temple priests) at Bhadrachalam on the banks of the river Godavari in Bhadradri Kothagudem district of Telangana, preparing and sharing Panakam which is a sweet drink prepared with jaggery and pepper, a procession and Rama temple decorations.

Ramlila and Dussehra

Rama's life is remembered and celebrated every year with dramatic plays and fireworks in autumn. This is called Ramlila, and the play follows Ramayana or more commonly the Ramcharitmanas.[115] It is observed through thousands[13] of Rama-related performance arts and dance events, that are staged during the festival of Navratri in India.[116] After the enactment of the legendary war between Good and Evil, the Ramlila celebrations climax in the Dussehra (Dasara, Vijayadashami) night festivities where the giant grotesque effigies of Evil such as of demon Ravana are burnt, typically with fireworks.[84][117]

The Ramlila festivities were declared by UNESCO as one of the "Intangible Cultural Heritages of Humanity" in 2008. Ramlila is particularly notable in historically important Hindu cities of Ayodhya, Varanasi, Vrindavan, Almora, Satna and Madhubani – cities in Uttar Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Bihar and Madhya Pradesh.[84][118] The epic and its dramatic play migrated into southeast Asia in the 1st millennium CE, and Ramayana based Ramlila is a part of performance arts culture of Indonesia, particularly the Hindu society of Bali, Myanmar, Cambodia and Thailand.[119]

Diwali

In some parts of India, Rama's return to Ayodhya and his coronation is the main reason for celebrating Diwali, also known as the Festival of Lights.

In Guyana, Diwali is marked as a special occasion and celebrated with a lot of fanfare. It is observed as a national holiday in this part of the world and some ministers of the Government also take part in the celebrations publicly. Just like Vijayadashmi, Diwali is celebrated by different communities across India to commemorate different events in addition to Rama's return to Ayodhya. For example, many communities celebrate one day of Diwali to celebrate the Victory of Krishna over the demon Narakasur.

Hindu arts in Southeast Asia

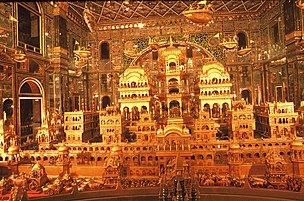

_(11804234493).jpg)

Rama's life story, both in the written form of Sanskrit Ramayana and the oral tradition arrived in southeast Asia in the 1st millennium CE.[121] Rama was one of many ideas and cultural themes adopted, others being the Buddha, the Shiva and host of other Brahmanic and Buddhist ideas and stories.[122] In particular, the influence of Rama and other cultural ideas grew in Java, Bali, Malaya, Burma, Thailand, Cambodia and Laos.[122]

The Ramayana was translated from Sanskrit into old Javanese around 860 CE, while the performance arts culture most likely developed from the oral tradition inspired by the Tamil and Bengali versions of Rama-based dance and plays.[121] The earliest evidence of these performance arts are from 243 CE according to Chinese records. Other than the celebration of Rama's life with dance and music, Hindu temples built in southeast Asia such as the Prambanan near Yogyakarta (Java), and at the Panataran near Blitar (East Java), show extensive reliefs depicting Rama's life.[121][123] The story of Rama's life has been popular in Southeast Asia.[124]

In the 14th century, the Ayutthaya Kingdom and its capital Ayuttaya was named after the Hindu holy city of Ayodhya, with the official religion of the state being Theravada Buddhism.[125][126] Thai kings, continuing into the contemporary era, have been called Rama, a name inspired by Rama of Ramakien – the local version of Sanskrit Ramayana, according to Constance Jones and James Ryan. For example, King Chulalongkorn (1853-1910) is also known as Rama V, while King Vajiralongkorn who succeeded to the throne in 2016 is called Rama X.[127]

Jainism

In Jainism, the earliest known version of Rama story is variously dated from the 1st to 5th century CE. This Jaina text credited to Vimalasuri shows no signs of distinction between Digambara-Svetambara (sects of Jainism), and is in a combination of Marathi and Sauraseni languages. These features suggest that this text has ancient roots.[128]

In Jain cosmology, characters continue to be reborn as they evolve in their spiritual qualities, until they reach the Jina state and complete enlightenment. This idea is explained as cyclically reborn triads in its Puranas, called the Baladeva, Vasudeva and evil Prati-vasudeva.[129][130] Rama, Lakshmana and evil Ravana are the eighth triad, with Rama being the reborn Baladeva, and Lakshmana as the reborn Vasudeva.[53] Rama is described to have lived long before the 22nd Jain Tirthankara called Neminatha. In the Jain tradition, Neminatha is believed to have been born 84,000 years before the 9th-century BCE Parshvanatha.[131]

Jain texts tell a very different version of the Rama legend than the Hindu texts such as by Valmiki. According to the Jain version, Lakshmana (Vasudeva) is the one who kills Ravana (Prativasudeva).[53] Rama, after all his participation in the rescue of Sita and preparation for war, he actually does not kill, thus remains a non-violent person. The Rama of Jainism has numerous wives as does Lakshmana, unlike the virtue of monogamy given to Rama in the Hindu texts. Towards the end of his life, Rama becomes a Jaina monk then successfully attains siddha followed by moksha.[53] His first wife Sita becomes a Jaina nun at the end of the story. In the Jain version, Lakshmana and Ravana both go to the hell of Jain cosmology, because Ravana killed many, while Lakshmana killed Ravana to stop Ravana's violence.[53] Padmapurana mentions Rama as a contemporary of Munisuvrata, 20th tirthankara of Jainism.[132]

Buddhism

The Dasaratha-Jataka (Tale no. 461) provides a version of the Rama story. It calls Rama as Rama-pandita.[97][98]

At the end of this Dasaratha-Jataka discourse, the Buddhist text declares that the Buddha in his prior rebirth was Rama:

The Master having ended this discourse, declared the Truths, and identified the Birth (...): 'At that time, the king Suddhodana was king Dasaratha, Mahamaya was the mother, Rahula's mother was Sita, Ananda was Bharata, and I myself was Rama-Pandita.

— Jataka Tale No. 461, Translator: W.H.D. Rouse[98]

While the Buddhist Jataka texts co-opt Rama and make him an incarnation of Buddha in a previous life,[98] the Hindu texts co-opt the Buddha and make him an avatar of Vishnu.[133][134] The Jataka literature of Buddhism is generally dated to be from the second half of the 1st millennium BCE, based on the carvings in caves and Buddhist monuments such as the Bharhut stupa.[135][note 4] The 2nd-century BCE stone relief carvings on Bharhut stupa, as told in the Dasaratha-Jataka, is the earliest known non-textual evidence of Rama story being prevalent in ancient India.[137]

Sikhism

Rama is mentioned as one of twenty four divine incarnations of Vishnu in the Chaubis Avtar, a composition in Dasam Granth traditionally and historically attributed to Guru Gobind Singh.[138] The discussion of Rama and Krishna avatars is the most extensive in this section of the secondary Sikh scripture.[138][139]

Among people

In Assam, Boro people call themselves Ramsa, which means Children of Ram.[140]

Worship and temples

Rama is a revered Vaishanava deity, one who is worshipped privately at home or in temples. He was a part of the Bhakti movement focus, particularly because of efforts of 14th century North Indian poet-saint Ramananda who created the Ramanandi Sampradaya, a sannyasi community. This community has grown to become the largest Hindu monastic community in modern times.[143][144] This Rama-inspired movement has championed social reforms, accepting members without discriminating anyone by gender, class, caste or religion since the time of Ramananda who accepted Muslims wishing to leave Islam.[145] Traditional scholarship holds that his disciples included later Bhakti movement poet-saints such as Kabir, Ravidas, Bhagat Pipa and others.[144][146]

Temples

Temples dedicated to Rama are found all over India and in places where Indian migrant communities have resided. In most temples, the iconography of Rama is accompanied by that of his wife Sita and brother Lakshmana. In some instances, Hanuman is also included either near them or in the temple premises.

Hindu temples dedicated to Rama were built by early 5th century, according to copper plate inscription evidence, but these have not survived. The oldest surviving Rama temple is near Raipur (Chhattisgarh), called the Rajiva-locana temple at Rajim near the Mahanadi river. It is in a temple complex dedicated to Vishnu and dates back to the 7th-century with some restoration work done around 1145 CE based on epigraphical evidence.[147][148] The temple remains important to Rama devotees in the contemporary times, with devotees and monks gathering there on dates such as Rama Navami.[149]

Important Rama temples include:

- Rama temple, Ram Janmabhoomi, Ayodhya

- Nalambalam, Kerala

- Bhadrachalam Temple, Telangana—built in 1674

- Kodandarama Temple, Vontimitta, Andhra Pradesh -built in 16th century

- Ramateertham Temple, Andhra Pradesh

- Ramaswamy Temple, Kumbakonam -built in 16th century

- Mudikondan Kothandaramar Temple - Bharadwaja ashram

- Vijayaraghava Perumal temple -built in 13th century

- Sri Yoga Ramar Temple Nedungunam, Tamil Nadu [150]

- Shree Rama Temple, Triprayar, Kerala

- Kalaram Temple, Nashik—built in 1788

- Raghunath Temple, Jammu—built in 1827

- Ram Mandir, Bhubaneswar, Odisha

- Kodandarama Temple, Chikmagalur -Built 14-16th century

- Kothandarama Temple, Thillaivilagam, Tamilnadu -Built 9-10th century

- Kothandaramaswamy Temple, Rameswaram

- Odogaon Raghunath Temple, Odisha—dates from Middle Ages

- Ramchaura Mandir, Bihar

- Sri Rama Temple, Ramapuram

In popular culture

Films

| Films | Played by |

|---|---|

| Lanka Dahan | Anna Salunke |

| Sita Kalyanam (1934 film) | S. Rajam |

| Ram Rajya | Prem Adib |

| Rambaan | |

| Ramayan (1954 film) | |

| Sampoorna Ramayanam (1958 film) | N. T. Rama Rao |

| Sampoorna Ramayana | Mahipal |

| Seeta Rama Kalyanam | Haranath |

| Indrajeet (Sati Sulochana) | Kanta Rao |

| Lava Kusa | N. T. Rama Rao |

| Ram Rajya (1967 film) | Kumar Sen |

| Sita Kalyanam (1976 film) | Ravi Kumar |

| Hanuman Vijay | Ashish Kumar |

| Bajrangbali (film) | Biswajit Chatterjee |

| Sri Rama Pattabhishekam | N. T. Rama Rao |

| Ramayana: The Legend of Prince Rama | Bryan Cranston (English version voice) |

| Arun Govil (Hindi version voice) | |

| Ramayanam (1996 film) | N. T. Rama Rao Jr. |

| Lav Kush | Jeetendra |

| Raavanan | Prithviraj Sukumaran (Based on Rama's character) |

| Ramayana: The Epic | Manoj Bajpayee (voice) |

| Sri Rama Rajyam | Nandamuri Balakrishna |

Television

| TV Series | Played by | Channel | Country |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ramayan (1987 TV series) | Arun Govil | DD National | India |

| Luv Kush | |||

| Bharat Ek Khoj | Salim Ghouse | ||

| Jai Hanuman (1997 TV series) | Siraj Mustafa Khan | DD Metro | |

| Om Namah Shivaya | Sandeep Mohan | DD National | |

| Vishnu Puran | Nitish Bharadwaj | Zee TV | |

| Ramayan (2002 TV series) | |||

| Ravanan | Diwakar Pundir | ||

| Ramayan (2008 TV series) | Gurmeet Choudhary | NDTV Imagine | |

| Jai Jai Jai Bajrang Bali | Shobhit Attray | Sahara One | |

| Devon Ke Dev...Mahadev | Piyush Sahdev | Life OK | |

| Ramleela – Ajay Devgn Ke Saath | Rajneesh Duggal | ||

| Ramayan (2012 TV series) | Gagan Malik | Zee TV | |

| Sankatmochan Mahabali Hanuman | Sony TV | ||

| Siya Ke Ram | Ashish Sharma | Star Plus | |

| Ram Siya Ke Luv Kush | Himanshu Soni | Colors TV | |

| Jag Janani Maa Vaishno Devi - Kahani Mata Rani Ki | Star Bharat |

See also

- Ayodhya dispute

- Culture of India

- Genealogy of Rama

- Hindu philosophy

- Natyashastra

- Ram Nam

- Ram Statue

- Tulsidas

References

Notes

- The legends found about Rama, state Mallory and Adams, have "many of the elements found in the later Welsh tales such as Branwen Daughter of Llyr and Manawydan Son of Lyr. This may be because the concept and legends have deeper ancient roots.[26]

- Kosala is mentioned in many Buddhist texts and travel memoirs. The Buddha idol of Kosala is important in the Theravada Buddhism tradition, and one that is described by the 7th-century Chinese pilgrim Xuanzhang. He states in his memoir that the statue stands in the capital of Kosala then called Shravasti, midst ruins of a large monastery. He also states that he brought back to China two replicas of the Buddha, one of the Kosala icon of Udayana and another the Prasenajit icon of Prasenajit.[35]

- For example, like other Hindu poet-saints of the Bhakti movement before the 16th century, Tulsidas in Ramcharitmanas recommends the simplest path to devotion is Nam-simran (absorb oneself in remembering the divine name "Rama"). He suggests either vocally repeating the name (jap) or silent repetition in mind (ajapajap). This concept of Rama moves beyond the divinised hero, and connotes "all pervading Being" and equivalent to atmarama within. The term atmarama is a compound of "Atma" and "Rama", it literally means "he who finds joy in his own self", according to the French Indologist Charlotte Vaudeville known for her studies on Ramayana and Bhakti movement.[81]

- Richard Gombrich suggests that the Jataka tales were composed by the 3rd century BCE.[136]

Citations

- James G. Lochtefeld 2002, p. 555.

- "Rama". Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- King, Anna S. (2005). The intimate other: love divine in Indic religions. Orient Blackswan. pp. 32–33. ISBN 978-81-250-2801-7.

- Matchett, Freda (2001). Krishna, Lord or Avatara?: the relationship between Krishna and Vishnu. 9780700712816. pp. 3–4. ISBN 978-0-7007-1281-6.

- James G. Lochtefeld (2002). The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism: N-Z. The Rosen Publishing Group. pp. 72–73. ISBN 978-0-8239-3180-4.

- Tulasīdāsa; RC Prasad (Translator) (1999). Sri Ramacaritamanasa. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 871–872. ISBN 978-81-208-0762-4.

- William H. Brackney (2013). Human Rights and the World's Major Religions, 2nd Edition. ABC-CLIO. pp. 238–239. ISBN 978-1-4408-2812-6.

- Roderick Hindery (1978). Comparative Ethics in Hindu and Buddhist Traditions. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 95–124. ISBN 978-81-208-0866-9.

- Vālmīki; Robert P Goldman (Translator) (1990). The Ramayana of Valmiki: Balakanda. Princeton University Press. p. 3. ISBN 9781400884551.

- Dimock Jr, E.C. (1963). "Doctrine and Practice among the Vaisnavas of Bengal". History of Religions. 3 (1): 106–127. doi:10.1086/462474. JSTOR 1062079.

- Marijke J. Klokke (2000). Narrative Sculpture and Literary Traditions in South and Southeast Asia. BRILL. pp. 51–57. ISBN 90-04-11865-9.

- Ramdas Lamb (2012). Rapt in the Name: The Ramnamis, Ramnam, and Untouchable Religion in Central India. State University of New York Press. pp. 28–32. ISBN 978-0-7914-8856-0.

- Schechner, Richard; Hess, Linda (1977). "The Ramlila of Ramnagar [India]". The Drama Review: TDR. The MIT Press. 21 (3): 51–82. doi:10.2307/1145152. JSTOR 1145152.

- James G. Lochtefeld (2002). The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism: 2 Volumes. The Rosen Publishing Group. p. 389. ISBN 978-0-8239-3180-4.

- Jennifer Lindsay (2006). Between Tongues: Translation And/of/in Performance in Asia. National University of Singapore Press. pp. 12–14. ISBN 978-9971-69-339-8.

- Roshen Dalal (2010). Hinduism: An Alphabetical Guide. Penguin Books. pp. 337–338. ISBN 978-0-14-341421-6.

- Peter J. Claus; Sarah Diamond; Margaret Ann Mills (2003). South Asian Folklore: An Encyclopedia : Afghanistan, Bangladesh, India, Nepal, Pakistan, Sri Lanka. Taylor & Francis. p. 508. ISBN 978-0-415-93919-5.

- Monier Monier Williams, राम, Sanskrit English Dictionary with Etymology, Oxford University Press, page 877

- Asko Parpola (1998). Studia Orientalia, Volume 84. Finnish Oriental Society. p. 264. ISBN 978-951-9380-38-4.

- Thomas William Rhys Davids; William Stede (1921). Pali-English Dictionary. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 521. ISBN 978-81-208-1144-7.

- Henk W. Wagenaar; S. S. Parikh (1993). Allied Chambers transliterated Hindi-Hindi-English dictionary. Allied Publishers. p. 528. ISBN 978-81-86062-10-4.

- "Ayodhya Case Verdict: Who is Ram Lalla Virajman, the 'Divine Infant' Given the Possession of Disputed Ayodhya Land". News18. 9 November 2019. Retrieved 4 August 2020.

- Rajarajan, R.K.K. (2001). Sītāpaharaṇam: Changing thematic Idioms in Sanskrit and Tamil. In Dirk W. Lonne ed. Tofha-e-Dil: Festschrift Helmut Nespital, Reinbeck, 2 vols., pp. 783-97. pp. 783–797. ISBN 3885870339.

- Adams; Douglas Q. Adams (2013). A Dictionary of Tocharian B: Revised and Greatly Enlarged. Rodopi. p. 587. ISBN 978-90-420-3671-0.

- J. P. Mallory; Douglas Q. Adams (1997). Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture. Taylor & Francis. p. 160. ISBN 978-1-884964-98-5.

- J. P. Mallory; Douglas Q. Adams (1997). Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture. Taylor & Francis. p. 165. ISBN 978-1-884964-98-5.

- Vālmīki; Sheldon I. Pollock (2007). The Rāmāyaṇa of Vālmīki: An Epic of Ancient India. Araṇyakāṇḍa. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 41 with footnote 83. ISBN 978-81-208-3164-3.

- Robin Rinehart (2004). Contemporary Hinduism: Ritual, Culture, and Practice. ABC-CLIO. pp. 139, 388. ISBN 978-1-57607-905-8.

- A. W. P. Guruge (1991). The Society of the Ramayana. Abhinav Publications. pp. 51–54. ISBN 978-81-7017-265-9.

- Valmiki Ramayana, Bala Kanda

- John Cort (2010). Framing the Jina: Narratives of Icons and Idols in Jain History. Oxford University Press. pp. 313 note 9. ISBN 978-0-19-973957-8.

- Winternitz, Moriz (1981). A History of Indian Literature, Volume 1. Motilal Banarsidass Publishers Private Limited. pp. 491–492. ISBN 81-208-0264-0.

- John Cort (2010). Framing the Jina: Narratives of Icons and Idols in Jain History. Oxford University Press. pp. 160–162, 196, 314 note 14, 318 notes 57–58. ISBN 978-0-19-973957-8., Quote (p. 314): "(...) Kosala was the kingdom centered on Ayodhya, in what is now east-central Uttar Pradesh."

- Peter van der Veer (1994). Religious Nationalism: Hindus and Muslims in India. University of California Press. pp. 157–162. ISBN 978-0-520-08256-4.

- John Cort (2010). Framing the Jina: Narratives of Icons and Idols in Jain History. Oxford University Press. pp. 194–200, 318 notes 57–58. ISBN 978-0-19-973957-8.

- Roderick Hindery (1978). Comparative Ethics in Hindu and Buddhist Traditions. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 106–107. ISBN 978-81-208-0866-9.

- Roshen Dalal (2010). Hinduism: An Alphabetical Guide. Penguin Books. pp. 326–327. ISBN 978-0-14-341421-6.

- Roshen Dalal (2010). Hinduism: An Alphabetical Guide. Penguin Books. pp. 99, 326–327. ISBN 978-0-14-341421-6.

- Roderick Hindery (1978). Comparative Ethics in Hindu and Buddhist Traditions. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 98–99. ISBN 978-81-208-0866-9.

- B. A van Nooten William (2000). Ramayana. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-22703-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Goldman Robert P (1996). The Ramayana of Valmiki. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-06662-2.

- Ramashraya Sharma (1986). A Socio-political Study of the Vālmīki Rāmāyaṇa. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 2–3. ISBN 978-81-208-0078-6.

- Gregory Claeys (2010). The Cambridge Companion to Utopian Literature. Cambridge University Press. pp. 240–241. ISBN 978-1-139-82842-0.

- Roderick Hindery (1978). Comparative Ethics in Hindu and Buddhist Traditions. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 100. ISBN 978-81-208-0866-9.

- Hess, L. (2001). "Rejecting Sita: Indian Responses to the Ideal Man's Cruel Treatment of His Ideal Wife". Journal of the American Academy of Religion. 67 (1): 1–32. doi:10.1093/jaarel/67.1.1. PMID 21994992. Retrieved 12 April 2008.

- Northrop Frye (2015). Northrop Frye's Uncollected Prose. University of Toronto Press. p. 191. ISBN 978-1-4426-4972-9.

- Dawn F. Rooney (2017). The Thiri Rama: Finding Ramayana in Myanmar. Taylor & Francis. p. 49. ISBN 978-1-315-31395-5.

- Paula Richman (1991). Many Rāmāyaṇas: The Diversity of a Narrative Tradition in South Asia. University of California Press. pp. 7–9 (by Richman), pp. 22–46 (Ramanujan). ISBN 978-0-520-07589-4.

- A.N. Jani (2005). Kodaganallur R.S. Iyengar (ed.). Asian Variations in Ramayana: Papers Presented at the International Seminar on 'Variations in Ramayana in Asia. Sahitya Akademi. pp. 29–55. ISBN 978-81-260-1809-3.

- Paula Richman (1991). Many Rāmāyaṇas: The Diversity of a Narrative Tradition in South Asia. University of California Press. pp. 10–12, 67–85. ISBN 978-0-520-07589-4.

- Monika Horstmann (1991). Rāmāyaṇa and Rāmāyaṇas. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. 9–21. ISBN 978-3-447-03116-5.

- Paula Richman (1991). Many Rāmāyaṇas: The Diversity of a Narrative Tradition in South Asia. University of California Press. pp. 11–12, 89–108. ISBN 978-0-520-07589-4.

- Padmanabh S Jaini (1993). Wendy Doniger (ed.). Purana Perennis: Reciprocity and Transformation in Hindu and Jaina Texts. State University of New York Press. pp. 216–219. ISBN 978-0-7914-1381-4.

- Umakant P. Shah (2005). Kodaganallur R.S. Iyengar (ed.). Asian Variations in Ramayana: Papers Presented at the International Seminar on 'Variations in Ramayana in Asia. Sahitya Akademi. pp. 57–76. ISBN 978-81-260-1809-3.

- Kapila Vatsyayan (2004). Mandakranta Bose (ed.). The Ramayana Revisited. Oxford University Press. pp. 335–339. ISBN 978-0-19-516832-7.

- Pattanaik, Devdutt (8 August 2020). "Was Ram born in Ayodhya". mumbaimirror.

- Dhirajlal Sankalia, Hasmukhlal (1982). The Ramayana in historical perspective. Macmillan India. pp. 4–5, 51.

- Swami Parmeshwaranand, Encyclopaedic Dictionary of Puranas - Volume 1, 2001. p. 44

- Simanjuntak, Truman (2006). Archaeology: Indonesian Perspective : R.P. Soejono's Festschrift. p. 361.

- John Brockington; Mary Brockington (2016). The Other Ramayana Women: Regional Rejection and Response. Routledge. pp. 3–6. ISBN 978-1-317-39063-3.

- Vālmīki. Śrīmad Vālmīki-Rāmāyaṇa: Araṇyakāṇḍa, Kiṣkindhā-kāṇḍa, and Sundara-kāṇḍa,Volume 2 of Śrīmad Vālmīki-Rāmāyaṇa: With Sanskrit Text and English Translation, Vālmīki. Gita Press, 1976. p. 1235.

- T. A. Gopinatha Rao (1993). Elements of Hindu iconography. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 189–193. ISBN 978-81-208-0878-2.

- Vālmīki; Sheldon I. Pollock (2007). The Rāmāyaṇa of Vālmīki: An Epic of Ancient India. Araṇyakāṇḍa. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 41–43. ISBN 978-81-208-3164-3.

- Roderick Hindery (1978). Comparative Ethics in Hindu and Buddhist Traditions. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 103–106. ISBN 978-81-208-0866-9.

- Gavin Flood (17 April 2008). THE BLACKWELL COMPANION TO HINDUISM. ISBN 978-81-265-1629-2.

- Roderick Hindery (1978). Comparative Ethics in Hindu and Buddhist Traditions. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 100–101. ISBN 978-81-208-0866-9.

- Constance Jones; James D. Ryan (2006). Encyclopedia of Hinduism. Infobase Publishing. p. 355. ISBN 978-0-8160-7564-5.

- Roshen Dalal (2010). Hinduism: An Alphabetical Guide. Penguin Books. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-14-341421-6.

- "The Oral Tradition and the many 'Ramayanas'", Moynihan @Maxwell, Maxwell School of Syracuse University's South Asian Center

- John Nicol Farquhar (1920). An Outline of the Religious Literature of India. Oxford University Press. pp. 324–325.

- Rocher 1986, pp. 158-159 with footnotes.

- RC Prasad (1989). Tulasīdāsa's Sriramacharitmanasa. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. xiv–xv, 875–876. ISBN 978-81-208-0443-2.

- R. Barz (1991). Monika Horstmann (ed.). Rāmāyaṇa and Rāmāyaṇas. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. 32–35. ISBN 978-3-447-03116-5.

- Ramcharitmanas, Encyclopaedia Britannica (2012)

- Lutgendorf 1991.

- Miller 2008, p. 217

- Varma 2010, p. 1565

- Poddar 2001, pp. 26–29

- Das 2010, p. 63

- Schomer & McLeod 1987, p. 75.

- Schomer & McLeod 1987, pp. 31-32 with footnotes 13 and 16 (by C. Vaudeville)..

- Schomer & McLeod 1987, pp. 31, 74-75 with footnotes, Quote: "What is striking about the dohas in the Ramcharitmanas however is that they frequently have a sant-like ring to them, breaking into the very midst of the saguna narrative with a statement of nirguna reality"..

- A Kapoor (1995). Gilbert Pollet (ed.). Indian Epic Values: Rāmāyaṇa and Its Impact. Peeters Publishers. pp. 181–186. ISBN 978-90-6831-701-5.

- Ramlila, the traditional performance of the Ramayana, UNESCO

- Chapple 1984, pp. x-xi with footnote 4

- Chapple 1984, pp. ix-xi

- Leslie 2003, pp. 105

- Chapple 1984, p. x

- Chapple 1984, pp. xi-xii

- Surendranath Dasgupta, A History of Indian Philosophy, Volume 2, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0521047791, pages 252-253

- Venkatesananda, S (Translator) (1984). The Concise Yoga Vāsiṣṭha. Albany: State University of New York Press. ISBN 0-87395-955-8.

- Pandit Rajmani Tigunait, Irene Petryszak (2002), The Himalayan Masters: A Living Tradition, pp 37, ISBN 978-0-89389-227-2

- White, David Gordon (2014). The "Yoga Sutra of Patanjali": A Biography. Princeton University Press. pp. xvi–xvii, 51. ISBN 978-0691143774.

- Edmour J. Babineau (1979). Love of God and Social Duty in the Rāmcaritmānas. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 85–86. ISBN 978-0-89684-050-8.

- Fallon, Oliver. 2009. Bhatti's Poem: The Death of Rávana (Bhaṭṭikāvya). New York: Clay Sanskrit Library . ISBN 978-0-8147-2778-2 | ISBN 0-8147-2778-6 |

- Roshen Dalal (2010). Hinduism: An Alphabetical Guide. Penguin Books. p. 323. ISBN 978-0-14-341421-6.

- H. T. Francis; E. J. Thomas (1916). Jataka Tales. Cambridge University Press (Reprinted: 2014). pp. 325–330. ISBN 978-1-107-41851-6.

- E.B. Cowell; WHD Rouse (1901). The Jātaka: Or, Stories of the Buddha's Former Births. Cambridge University Press. pp. 78–82.

- Jaiswal, Suvira (1993). "Historical Evolution of Ram Legend". Social Scientist. 21 (3 / 4 March April 1993): 89–96. doi:10.2307/3517633. JSTOR 3517633.

- Rocher 1986, p. 84 with footnote 26.

- J. A. B. van Buitenen (1973). The Mahabharata, Volume 2: Book 2: The Book of Assembly; Book 3: The Book of the Forest. University of Chicago Press. pp. 207–214. ISBN 978-0-226-84664-4.

- Paula Richman (1991). Many Rāmāyaṇas: The Diversity of a Narrative Tradition in South Asia. University of California Press. pp. 17 note 11. ISBN 978-0-520-07589-4.

- Robert Goldman (2013), The Valmiki Ramayana, Center for South Asia Studies, University of California at Berkeley

- P S Sundaram (2002). Kamba Ramayana. Penguin Books. pp. 1–2. ISBN 978-93-5118-100-2.

- James G. Lochtefeld (2002). The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism: N-Z. The Rosen Publishing Group. p. 562. ISBN 978-0-8239-3180-4.

- The nine-day festival of Navratri leading up to Sri Rama Navami has bhajans, kirtans and discourses in store for devotees Archived 7 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine Indian Express, Friday, 31 March 2006.

- Ramnavami The Times of India, 2 April 2009.

- Ram Navami BBC.

- "President and PM greet people as India observes Ram Navami today". IANS. news.biharprabha.com. 8 April 2014. Retrieved 8 April 2014.

- Ramnavami Govt. of India Portal.

- Hindus around the world celebrate Ram Navami today, DNA, 8 April 2014

- Sitamarhi, Encyclopedia Britannica (2014), Quote: "A large Ramanavami fair, celebrating the birth of Lord Rama, is held in spring with considerable trade in pottery, spices, brass ware, and cotton cloth. A cattle fair held in Sitamarhi is the largest in Bihar state. The town is sacred as the birthplace of the goddess Sita (also called Janaki), the wife of Rama."

- On Ram Navami, we celebrate our love for the ideal Archived 7 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine Indian Express, Monday, 31 March 2003.

- Shobha yatra on Ram Navami eve Archived 7 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine Indian Express, Thursday, 25 March 1999.

- James G. Lochtefeld 2002, p. 389.

- Encyclopedia Britannica 2015.

- Ramlila Pop Culture India!: Media, Arts, and Lifestyle, by Asha Kasbekar. Published by ABC-CLIO, 2006. ISBN 1-85109-636-1. Page 42.

- James G. Lochtefeld 2002, pp. 561-562.

- Mandakranta Bose (2004). The Ramayana Revisited. Oxford University Press. pp. 342–350. ISBN 978-0-19-516832-7.

- Willem Frederik Stutterheim (1989). Rāma-legends and Rāma-reliefs in Indonesia. Abhinav Publications. pp. 109–160. ISBN 978-81-7017-251-2.

- James R. Brandon (2009). Theatre in Southeast Asia. Harvard University Press. pp. 22–27. ISBN 978-0-674-02874-6.

- James R. Brandon (2009). Theatre in Southeast Asia. Harvard University Press. pp. 15–21. ISBN 978-0-674-02874-6.

- Jan Fontein (1973), The Abduction of Sitā: Notes on a Stone Relief from Eastern Java, Boston Museum Bulletin, Vol. 71, No. 363 (1973), pp. 21-35

- Kats, J. (1927). "The Ramayana in Indonesia". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. Cambridge University Press. 4 (3): 579. doi:10.1017/s0041977x00102976.

- Francis D. K. Ching; Mark M. Jarzombek; Vikramaditya Prakash (2010). A Global History of Architecture. John Wiley & Sons. p. 456. ISBN 978-0-470-40257-3., Quote: "The name of the capital city [Ayuttaya] derives from the Hindu holy city Ayodhya in northern India, which is said to be the birthplace of the Hindu god Rama."

- Michael C. Howard (2012). Transnationalism in Ancient and Medieval Societies: The Role of Cross-Border Trade and Travel. McFarland. pp. 200–201. ISBN 978-0-7864-9033-2.

- Constance Jones; James D. Ryan (2006). Encyclopedia of Hinduism. Infobase Publishing. p. 443. ISBN 978-0-8160-7564-5.

- John E Cort (1993). Wendy Doniger (ed.). Purana Perennis: Reciprocity and Transformation in Hindu and Jaina Texts. State University of New York Press. p. 190. ISBN 978-0-7914-1381-4.

- Jacobi, Herman (2005). Vimalsuri's Paumachariyam (2nd ed.). Ahemdabad: Prakrit Text Society.

- Iyengar, Kodaganallur Ramaswami Srinivasa (2005). Asian Variations In Ramayana. Sahitya Akademi. ISBN 978-81-260-1809-3.

- Zimmer 1953, p. 226.

- Natubhai Shah 2004, pp. 21-23.

- Daniel E Bassuk (1987). Incarnation in Hinduism and Christianity: The Myth of the God-Man. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 40. ISBN 978-1-349-08642-9.

- Edward Geoffrey Parrinder (1997). Avatar and Incarnation: The Divine in Human Form in the World's Religions. Oxford: Oneworld. pp. 19–24, 35–38, 75–78, 130–133. ISBN 978-1-85168-130-3.

- Peter J. Claus; Sarah Diamond; Margaret Ann Mills (2003). South Asian Folklore: An Encyclopedia. Taylor & Francis. pp. 306–307. ISBN 978-0-415-93919-5.

- Naomi Appleton (2010). Jātaka Stories in Theravāda Buddhism: Narrating the Bodhisatta Path. Ashgate Publishing. pp. 51–54. ISBN 978-1-4094-1092-8.

- Mandakranta Bose (2004). The Ramayana Revisited. Oxford University Press. pp. 337–338. ISBN 978-0-19-803763-7.

- Robin Rinehart (2011). Debating the Dasam Granth. Oxford University Press. pp. 29–30, 14. ISBN 978-0-19-984247-6.

- Doris R. Jakobsh (2010). Sikhism and Women: History, Texts, and Experience. Oxford University Press. pp. 47–48. ISBN 978-0-19-806002-4.

- (Dodiya 2001:139)

- Monika Horstmann (1991). Rāmāyaṇa and Rāmāyaṇas. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. 72–73 with footnotes. ISBN 978-3-447-03116-5.

- Hans Bakker (1990). The History of Sacred Places in India As Reflected in Traditional Literature: Papers on Pilgrimage in South Asia. BRILL. pp. 70–73. ISBN 90-04-09318-4.

- Selva Raj and William Harman (2007), Dealing with Deities: The Ritual Vow in South Asia, State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-0791467084, pages 165-166

- James G Lochtefeld (2002), The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism: N-Z, Rosen Publishing, ISBN 978-0823931804, pages 553-554

- Gerald James Larson (1995), India's Agony Over Religion, State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-0791424124, page 116

- David Lorenzen, Who Invented Hinduism: Essays on Religion in History, ISBN 978-8190227261, pages 104-106

- J. L. Brockington (1998). The Sanskrit Epics. BRILL. pp. 471–472. ISBN 90-04-10260-4.

- Meister, Michael W. (1988). "Prasada as Palace: Kutina Origins of the Nagara Temple". Artibus Asiae. 49 (3/4): 254–280 (Figure 21). doi:10.2307/3250039. JSTOR 3250039.

- James C. Harle (1994). The Art and Architecture of the Indian Subcontinent. Yale University Press. pp. 148–149, 207–208. ISBN 978-0-300-06217-5.

- "Pilgrimage to Vishnu Sthalas - 8th February 2015".

Sources

- Chapple, Christopher (1984). "Introduction". The Concise Yoga Vāsiṣṭha. Translated by Venkatesananda, Swami. Albany: State University of New York Press. ISBN 0-87395-955-8. OCLC 11044869.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Das, Krishna (15 February 2010), Chants of a Lifetime: Searching for a Heart of Gold, Hay House, Inc, ISBN 978-1-4019-2771-4

- "Navratri – Hindu festival". Encyclopedia Britannica. 21 February 2017. Retrieved 21 February 2017.

- Flood, Gavin (17 April 2008). The Blackwell Companion to Hinduism. Wiley India Pvt. Limited. ISBN 978-81-265-1629-2.

- Hertel, Bradley R.; Humes, Cynthia Ann (1993). Living Banaras: Hindu Religion in Cultural Context. SUNY Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-1331-9.

- Miller, Kevin Christopher (2008). A Community of Sentiment: Indo-Fijian Music and Identity Discourse in Fiji and Its Diaspora. ISBN 978-0-549-72404-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Leslie, Julia (2003). Authority and meaning in Indian religions: Hinduism and the case of Vālmīki. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. ISBN 0-7546-3431-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Morārībāpu (1987). Mangal Ramayan. Prachin Sanskriti Mandir.

- Poddar, Hanuman Prasad (2001). Balkand. 94 (in Awadhi and Hindi). Gorakhpur, India: Gita Press. ISBN 81-293-0406-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- James G. Lochtefeld (2002). The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism: N-Z. The Rosen Publishing Group. ISBN 0-8239-2287-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lutgendorf, Philip (1991). The Life of a Text: Performing the Rāmcaritmānas of Tulsidas. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-06690-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Naidu, S. Shankar Raju (1971). A Comparative Study of Kamba Ramayanam and Tulasi Ramayan. University of Madras.

- Platvoet, Jan. G.; Toorn, Karel Van Der (1995). Pluralism and Identity: Studies in Ritual Behaviour. BRILL. ISBN 90-04-10373-2.

- Rocher, Ludo (1986). The Puranas. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 978-3447025225.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Schomer, Karine; McLeod, W. H. (1 January 1987), The Sants: Studies in a Devotional Tradition of India, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-0277-3

- Shah, Natubhai (2004) [First published in 1998], Jainism: The World of Conquerors, I, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 81-208-1938-1

- Stasik, Danuta; Trynkowska, Anna (1 January 2006). Indie w Warszawie: tom upamiętniający 50-lecie powojennej historii indologii na Uniwersytecie Warszawskim (2003/2004). Dom Wydawniczy Elipsa. ISBN 978-83-7151-721-1.

- Varma, Ram (1 April 2010). Ramayana : Before He Was God. Rupa & Company. ISBN 978-81-291-1616-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Zimmer, Heinrich (1953) [April 1952], Campbell, Joseph (ed.), Philosophies Of India, Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd, ISBN 978-81-208-0739-6

- Dodiya, Jaydipsinh (2001), Critical Perspectives on the Rāmāyaṇa, Sarup & Sons, p. 139, ISBN 9788176252447

Further reading

- Jain Rāmāyaṇa of Hemchandra (English translation), book 7 of the Trishashti Shalaka Purusha Caritra, 1931

- Ramayana, translated in English by Griffith, from Project Gutenberg

- Willem Frederik Stutterheim (1989). Rāma-legends and Rāma-reliefs in Indonesia. Abhinav Publications. ISBN 978-81-7017-251-2.

- Vyas, R.T. (ed.) Vālmīki Rāmāyaṇa, Text as Constituted in its Critical Edition, Oriental Institute, Vadodara, 1992.

- Valmiki Ramayana, Gita Press, Gorakhpur, India.

- Ramesh Menon, The Ramayana: A Modern Retelling of the Great Indian Epic ISBN 0-86547-660-8

- F.S. Growse, The Ramayana of Tulsidas

- Jonah Blank, Arrow of the Blue-Skinned God: Retracing the Ramayana Through India ISBN 0-8021-3733-4

- Kambar, Kamba Ramayanam.

External links

- Rama at Encyclopædia Britannica

- Rama and Sita in Wonoboyo, Willem van der Molen (2003), Brill (10th century Indonesian treasure discovered in 1990)

.jpg)