Dasam Granth

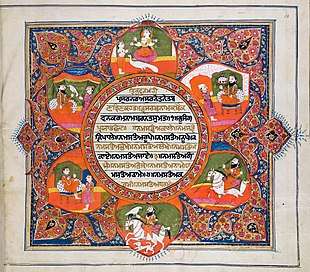

The Dasam Granth (Gurmukhi: ਦਸਮ ਗ੍ਰੰਥ, lit. "the Book of the Tenth Guru"), also called the Dasven Pādśāh kā Graṅth, (Gurmukhi: ਦਸਮ ਗ੍ਰੰਥ), is a holy book in Sikhism with compositions attributed to Guru Gobind Singh.[1][2] It is a controversial religious text considered to be the second scripture by some Sikhs, and of disputed authority by other Sikhs.[3] The standard edition of the text contains 1,428 pages with 17,293 verses in 18 sections.[3][1] These are set in the form of hymns and poems mostly in the Braj language (Old western Hindi),[3] with some parts in Avadhi, Punjabi, Hindi and Persian.[1] The script is almost entirely the Gurmukhi script except for the letter of the Sikh Guru to Aurangzeb – Zafarnama, and the Hikayat in the Persian alphabet.[1]

| Part of a series on |

| Sikhism |

|---|

|

|

|

Practices

|

|

|

General topics

|

The Dasam Granth includes hymns, mythological tales from Hindu texts,[2] a celebration of the feminine in the form of goddess Durga,[4] erotic fables,[2] an autobiography, letters to others such as the Mughal emperor, as well as reverential discussion of warriors and theology.[3] It is a religious text, separate from the Guru Granth Sahib, one considered as Sikhism's second scripture in its history.[5] It is controversial, of disputed authorship, and seldom recited in full within Sikh gurdwaras (temples) in the contemporary era.[5][6] Parts of it are popular and sacred among Sikhs, recited during Khalsa initiation and other daily devotional practices by devout Sikhs.[5] Such compositions of the Dasam Granth include Jaap Sahib, Tav-Prasad Savaiye and Benti Chaupai which are part of the Nitnem or daily prayers and also part of the Amrit Sanchar or baptism ceremony of Khalsa Sikhs.[7]

The oldest known manuscript of Dasam Granth is likely the Anandpuri bir. Almost all of the pages in it are dated to the 1690s, with a few folio pages on Zafarnama and Hikayats in a different style and format appended to it in the early 18th century.[6] Other important manuscripts include the Patna bir (1698 CE) and the Mani Singh Vali bir (1713). These manuscripts include the Indian mythologies that are questioned by some Sikhs in the contemporary era, as well as sections such as the Ugradanti and Sri Bhagauti Astotra that were, for some reason, removed from these manuscripts in the official versions of Dasam Granth in the 20th century.[6]

Authorship

| Part of a series on |

| Dasam Granth |

|---|

|

| Dasam Granth - (ਦਸਮ ਗ੍ਰੰਥ ਸਾਹਿਬ) |

| Banis |

|

| Other Related Banis |

|

| Various aspects |

| Idolatry Prohibition |

Although the compositions of the Dasam Granth are widely accepted to be penned by Guru Gobind Singh there are some that question the authenticity of the Dasam Granth. There are three major views on the authorship of the Dasam Granth:[8]

- The historical and traditional view is that the entire work was composed by Guru Gobind Singh himself.

- The entire collection was composed by the poets in the Guru's entourage.

- Only a part of the work was composed by the Guru, while the rest was composed by the other poets.

In his religious court at Anandpur Sahib, Guru Gobind Singh had employed 52 poets, who translated several classical texts into Braj Bhasha. Most of the writing compiled at Anandpur Sahib was lost while the Guru's camp was crossing the Sirsa river before the Battle of Chamkaur in 1704. There were copiers available at the Guru's place who made several copies of the writings. Later, Bhai Mani Singh compiled all the available works under the title Dasam Granth.

The traditional scholars claim that all the works in Dasam Granth were composed by the Guru himself, on the basis of Bhai Mani Singh's letter. But the veracity of the letter has been examined by scholars and found to be unreliable. An example of varying style can be seen in the sections 'Chandi Charitar' and 'Bhagauti ki War' . Some others dispute the claim of the authorship, saying that some of the compositions included in Dasam Granth such as Charitropakhyan are "out of tune" with other Sikh scriptures, and must have been composed by other poets.[9] The names of poets Raam, Shyam and Kaal appear repeatedly in the granth. References to Kavi Shyam can be seen in Mahan Kosh of Bhai Kahan Singh Nabha, under the entry 'Bawanja Kavi' and also in Kavi Santokh Singh's magnum opus Suraj Prakash Granth.

Historical writings

The following are historical books after the demise of Guru Gobind Singh which mention that the compositions in the present Dasam Granth was written by Guru Gobind Singh:

- Rehitnama Bhai Nand Lal mentioned Jaap Sahib is an important Bani for a Sikh.[10]

- Rehitnama Chaupa Singh Chibber quotes various lines from Bachitar Natak, 33 Swiayey, Chopai Sahib, Jaap Sahib.[11]

- In 1711, Sri Gur Sobha was written by the poet Senapat and mentioned a conversation of Guru Gobind Singh and Akal Purakh, and written three of its Adhyay on base of Bachitar Natak.[12]

- In 1741, Parchian Srvadas Kian quoted lines from Rama Avtar, 33 Swaiyey and mentioned Zafarnama with Hikayats.[13]

- in 1751, Gurbilas Patshahi 10 – Koyar Singh Kalal, mentioned Guru Gobind Singh composed Bachitar Natak, Krisna Avtar, Bisan Avtar, Akal Ustat, Jaap Sahib, Zafarnama, Hikayats etc. This is first Granth mentioned Guruship of Guru Granth Shahib.[14]

- In 1766, Kesar Singh Chibber mentioned history of compilation of Dasam Granth by Bhai Mani Singh Khalsa on directions of Mata Sundri, as he was first who wrote history after death of Guru Gobind Singh.

- In 1766, Sri Guru Mahima Parkash – Sarup Chand Bhalla, mentioned about various Banis of Guru Gobind Singh and compilation of Dasam Granth

- In 1790, Guru Kian Sakhian – Svarup Singh Kashish, mentioned Guru Gobind Singh composed, bachitar Natak, Krishna Avtar, Shastarnaam Mala, 33 Swaiyey etc.

- In 1797, Gurbilas Patshahi 10 – Sukkha Singh, mentioned compositions of Guru Gobind Singh.

- In 1812, J. B. Malcolm, in SKetch of Sikhs mentioned about Dasam Granth as Bani of Guru Gobind Singh.

Structure

The standard print edition of the Dasam Granth, since 1902, has 1,428 pages.[3][1] However, many printed versions of the text in the contemporary era skip a major section (40%) because it is considered too graphic and obscene to print for the general audience.[15]

The standard official edition contains 17,293 verses in 18 sections.[3][1] These are set in the form of hymns and poems mostly in the Braj Bhasha (Old western Hindi),[3] with some parts in Avadhi, Punjabi, Hindi and Persian language.[1] The script is almost entirely the Gurmukhi script except for the letter of the Sikh Guru to Aurangzeb – Zafarnama, and the Hikayat in the Persian script.[1]

Contents

The Dasam Granth has 18 sections convering a wide range of topics:

| No. | Bani Title | Alternate Name | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Jaap Sahib | Jaap Sahib | a prayer of 199 verses dedicated to formless, timeless, all-pervading god.[16] |

| 2 | Akal Ustat | A praise of the timeless primal being Akal Purakh (god), explaining that this primal being takes numerous forms of gods and goddesses, listing most frequently Hindu names of these, but also includes a few Muslim epithets.[16] Criticizes overemphasis on rituals related to the devotional worship of god.[16] | |

| 3 | Bachittar Natak | Bachitra Natak | Partly an autobiography that states he was born in Sodhi lineage, tracing it to the lineage of Rama and Sita of Ramayana;[17] mentions Guru Nanak was born in the Bedi clan and how the next eight Gurus came to lead the Sikhs; describes the persecution and execution of Guru Tegh Bahadur calling him the defender of dharma who protected the sacred threads and the tilaks (forehead mark of devout Hindus);[17] he mentions his own rebirth in Patna after God explained to him that he had sent religious leaders to earth, in forms such as Muhammad but these clung to their own self-interest rather than promote devotion to the true God;[17] He took birth to defend and spread the dharma, and was blessed by god to remember his past births;[17] the Bachitra Natak criticizes those who take pride in their religious rituals, mentions his own hunting expeditions, battles and journeys in Punjab and the Himalayan foothills.[17] |

| 4 | Chandi Charitar Ukti Bilas | Chandi Charitar 1 | a discussion of the Hindu goddess, Durga in the form of Chandi; this section of the Dasam Granth declares that it is based on the Sanskrit text Markandeya Purana; it glorifies the feminine with her fighting the mythical war between good and evil, after the gods have admitted their confusion and weakness, she anticipating and thus defeating evil that misleads and morphs into different shapes.[17] |

| 5 | Chandi Charitar II | Chandi Charitar 2 | a retelling of the story of the Hindu goddess, Durga again in the form of Chandi; it again glorifies the feminine with her fighting the war between good and evil, and in this section she slays the buffalo-demon Mahisha, all his associates and supporters thus bringing an end to the demonic violence and war.[17] |

| 6 | Chandi di Var | Var Durga Ki | the ballad of Hindu goddess, Durga, in Punjabi; this section of the Dasam Granth states that it is based on the Sanskrit text Durga Saptasati;[18] The opening verses from this composition, states Robin Rinehart, have been a frequently recited ardas petition or prayer in Sikh history;[18] it is also a source of controversy within Sikhism, as the opening verse states "First I remember Bhagauti, then I turn my attention to Guru Nanak"; the dispute has been whether one should interpret of the word "Bhagauti" as "goddess" or a metaphor for "sword".[18] |

| 7 | Gyan Prabodh | Gyan Prabodh, Parbodh Chandra Natak | The section title means "the Awakening of Knowledge", and it begins with praise of God; it includes a conversation between soul and God, weaves in many references to Hindu mythology and texts such as the Mahabharata;[19] the section summarizes those parva of the Hindu epic which discuss kingship and dharma; the role of Brahmins and Kshatriya varnas.[19] |

| 8 | Chaubis Avtar | Avatars of Vishnu, Chaubis Avtar | this is a lengthy section of the Dasam Granth, covering about a third of the entire book; narrates 24 incarnations of the Hindu god Vishnu;[19] this list includes Brahma, Rudra, Buddha of Buddhism, and Kalki;[19] the largest subsections of the Chaubis Avatar are dedicated to Rama and Krishna;[19] the section also includes verse 434 which states "I do not honor Ganesha, nor do I ever meditate on Krishna or Vishnu, I have heard of them but I know them not. I love only God's feet";[20] Similarly, verse 863 states "Since I embraced thy feet, I have paid homage to none besides; the Puranas speak of Ram, and the Quran of Rahim, but I accept none of them";[20] these verses have been used by Sikh commentators as evidence that Guru Gobind Singh taught a distinct Sikh identity, and did not encourage the worship of Hindu deities;[19] according to other Sikh commentators, these verses parallel the significance given to the unmanifested, nirguna Brahman – the metaphysical concept in the Vedantic school of Hinduism;[21][22][23] |

| 9 | Brahma Avtar | Avatars of Brahma | Narrative on the seven incarnations of Brahma, who is already mentioned in the Chaubis Avatar section[19] |

| 10 | Rudra Avtar | Avatars of Rudra | a poem that narrates Rudra and his avatars, also already mentioned in the Chaubis Avatar section[19] |

| 11 | Shabad Hazare | Thousand hymns | actually contains nine hymns, each set to a raga (melody), with content similar to Chaubis Avatar section; the sixth is filled with grief and generally understood to have been composed by Guru Gobind Singh after the loss of all four sons in the wars with the Mughal Empire;[19] this section is missing in some early manuscripts of Dasam Granth.[19] |

| 12 | Savaiye | Swayyee | thirty-three verses that praise a god; asserts the mystery of god who is beyond what is in the Vedas and Puranas (Hindu), as well as beyond the one in Quran (Muslim).[24] |

| 13 | Khalsa Mahima | Praise of Khalsa | a short passage that explains why offerings to goddess Naina Devi by the general public are distributed to the Khalsa soldiers rather than Brahmin priests.[24] |

| 14 | Ath Sri Shastar Naam Mala Purana Likhyate | Shastar nam mala | The section title means a "garland of weapon names", and it has 1,300 verses;[24] it lists and exalts various weapons of violence, declaring them to be symbols of God's power, states Rinehart;[24] it includes the names of Hindu deities and the weapon they carry in one or more of their hands, and praises their use and virtues; the list includes weapons introduced in the 17th-century such as a rifle; some of the verses are riddles about weapons.[24] |

| 15 | Sri Charitropakhyan | Charitropakhian, Pakhyan Charitra, Tria Charitra | the largest part of the Dasam Granth (40%), it is a controversial section;[25] it includes over 400 character features and behavioral sketches;[25] these are largely characters of lustful women seeking extramarital sex and seducing men for love affairs without their husbands knowing; the characters delight in gambling, opium and liquor;[25] these stories either end in illustrating human weaknesses with graphic description of sexual behavior, or illustrate a noble behavior where the seduction target refuses and asserts that "he cannot be a dharmaraja if he is unfaithful to his wife";[25] the section is controversial, sometimes interpreted as a didactic discussion of virtues and vices; the charitras 21 through 23 have been interpreted by some commentators as possibly relating to Guru Gobind Singh's own life where he refused a seduction attempt;[25] the final charitra (number 404) describes the Mughals and Pathans as offsprings of demons, details many battles between gods and demons, ending with the victory of gods; the Benti Chaupai found in this last charitra is sometimes separated from its context by Sikhs and used or interpreted in other ways;[25] Many modern popular print editions of Dasam Granth omit this section possibly because of the graphic nature; a few Sikh commentators have questioned the authorship of Dasam Granth in significant part because of this section, while others state that the text must be viewed in the perspective of the traumatic period of Sikh history when Guru Gobind Singh and his soldier disciples were fighting the Mughal Empire and this section could have been useful for the moral edification of soldiers at the war front against the vice.[25][note 1] |

| 16 | Chaupai Sahib | Kabyo Bach Benti Chaupai | A part of the last charitra of the Charitropakhian section above; it is sometimes separated and used independently.[25] |

| 17 | Zafarnamah | Epistle of victory | A letter written in 1706 by Guru Gobind Singh to Emperor Aurangzeb in Persian language;[27] it chastises the Mughal emperor for promising a safe passage to his family but then reneging on that promise, attacking and killing his family members;[28] |

| 18 | Hikayat | Hikaitan | Usually grouped with the Zafarnama section, these are twelve tales unrelated to Zafarnama but probably linked because some versions have these in Persian language; the content of this section is closer in form and focus to the Charitropakhian section above;[28] |

Deleted subsections

Some birs (old manuscript recensions) also include the following compositions:

Role in Sikh liturgy, access

The compositions within Dasam Granth play a huge role in Sikh liturgy, which is prescribed by Sikh Rehat Maryada:

- Jaap Sahib is part of Nitnem, which Sikh recites daily in morning.[29][30]

- Tav-Prasad Savaiye, again a bani of Nitnem, is part of Akal Ustat composition, which is recited daily in morning along with above.[29]

- Benti Chaupai, is part of Sri Charitropakhyan, which is recited in morning as well as evening prayers.[30]

- Jaap, Tav Prasad Savaiye and Chaupai are read while preparing Khande Batey Ki Pahul for Khalsa initiation.[7]

- The first stanza of the Sikh ardās is from Chandi di Var.[7]

- As per Sikh Rehat Maryada, a stanza of Chaubis Avtar, "pae gahe jab te tumre", should be comprised in So Dar Rehras.[31]

In the Nirankari tradition – considered heretical by the Khalsa Sikhs,[32] the Dasam Granth is given equal scriptural status as the Adi Granth (first volume).[33] Chandi di Var is also an important prayer among Nihang and Namdhari Sikhs.

Except for the liturgical portions and some cherrypicked verses of the Dasam Granth that are widely shared and used, few Sikhs have read the complete Dasam Granth or know its contents.[34] Most do not have access to it in its entirety (1,428 pages), as the generic printed or translated versions do not include all its sections and verses.[25] In its history, the entire text was in the active possession of the Khalsa soldiers.[note 2]

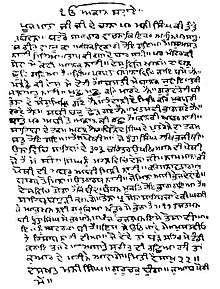

Manuscripts

The oldest known manuscript of Dasam Granth is likely the Anandpuri bir. It is dated to the 1690s, but a few folio pages on Zafarnama and Hikayats were definitely added later, because they are composed after 1700, are in a different style and format, lacking the folio numbers present on all pages elsewhere. These letters of Guru Gobind Singh were likely appended to it in the early 18th century.[6] According to another view, the earliest surviving manuscript of the complete text is dated to 1713, and the early manuscript versions have minor variations.[34]

Other important manuscripts include the Patna bir (1698 CE) found in Bihar, and the Mani Singh Vali bir (1713) found in Punjab. The Mani Singh bir includes hymns of the Banno version of the Adi Granth. It is also unique in that it presents the Zafarnama and Hikayats in both Perso-Arabic Nastaliq script and the Gurmukhi script.[6] The Bhai Mani Singh manuscript of Dasam Granth has been dated to 1721, was produced with the support of Mata Sundari, states Gobind Mansukhani.[36]

The early Anandpuri, Patna and Mani Singh manuscripts include the Indian mythologies that are disputed in the contemporary era, as well as sections such as the Ugradanti and Sri Bhagauti Astotra that were, for some reason, removed from these manuscripts in the official versions of Dasam Granth in the 20th century by Singh Sabha Movement activists.[6]

According to the Indologist Wendy Doniger, many orthodox Sikhs credit the authorship and compilation of the earliest Dasam Granth manuscript to Guru Gobind Singh directly, while other Sikhs and some scholars consider the text to have been authored and compiled partly by him and partly by many poets in his court at Anandpur.[34]

Prior to 1902, there were numerous incomplete portions of manuscripts of Dasam Granth in circulation within the Sikh community along with the complete, but somewhat variant, major versions such as the Anandpuri and Patna birs.[37] In 1885, during the Singh Sabha Movement, an organization called the Gurmat Granth Pracharak Sabha was founded by Sikhs to study the Sikh literature. This organization, with a request from Amritsar Singh Sabha, established the Sodhak Committee in 1897.[37] The members of this committee studied 32 manuscripts of Dasam Granth from different parts of the Indian subcontinent. The committee deleted some hymns found in the different old manuscripts of the text, merged the others and thus created a 1,428-page version thereafter called the standard edition of the Dasam Granth. The standard edition was first published in 1902.[37] It is this version that has predominantly been distributed to scholars and studied in and outside India. However, the prestige of the Dasam Granth was well established in the Sikh community during the Sikh Empire, as noted in 1812 by colonial-era scholar Malcolm.[37] According to Robin Rinehart – a scholar of Sikhism and Sikh literature, modern copies of the Dasam Granth in Punjabi, and its English translations, often do not include the entire standard edition text and do not follow the same ordering either.[3]

See also

Notes

- This view is supported by a remark found in Bansavalinama. This remark states that scribes offered to Guru Gobind Singh to merge Adi Granth and his compositions into one scripture. He replied that they should not do so, keep the two separate because his compositions are mostly khed (entertainment).[26]

- According to Giani Gian Singh, the full copy of the Dasam Granth was in possession of the Dal Khalsa (Sikh Army), an 18th-century Sikh army, at the Battle of Kup and was lost during the Sikh holocaust of 1762.[35]

References

- Singha, H. S. (2000). The Encyclopedia of Sikhism (over 1000 Entries). Hemkunt Press. ISBN 978-81-7010-301-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link), pp. 53–54

- Dasam Granth, Encyclopaedia Britannica

- Robin Rinehart (2014). Pashaura Singh and Louis E Fenech (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Sikh Studies. Oxford University Press. pp. 136–138. ISBN 978-0-19-969930-8.

- Eleanor Nesbitt (2016). Sikhism: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press. pp. 107–109. ISBN 978-0-19-106277-3.

- McLeod, W. H. (1990). Textual Sources for the Study of Sikhism. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-56085-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link), pages 2, 67

- Louis E. Fenech; W. H. McLeod (2014). Historical Dictionary of Sikhism. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. pp. 92–94. ISBN 978-1-4422-3601-1.

- Knut A. Jacobsen; Kristina Myrvold (2012). Sikhs Across Borders: Transnational Practices of European Sikhs. A&C Black. pp. 233–234. ISBN 978-1-4411-1387-0.

- McLeod, W. H. (2005). Historical dictionary of Sikhism. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 52. ISBN 978-0-8108-5088-0.

- Amaresh Datta, ed. (2006). The Encyclopaedia of Indian Literature (Volume One (A To Devo), Volume 1. Sahitya Akademi. p. 888. ISBN 978-81-260-1803-1.

- Rehitnama Bhai Nand Lal

- Rehitnama Chaupa Singh Chibber

- Sri Gur Sbha Granth, Poet Senapat, Piara Singh Padam

- Parchi Sevadas Ki, Poet Sevada, Piara Singh Padam

- Gurbilas, Patshahi 10, Koer Singh, Bhasha Vibagh, Punjabi University

- Knut A. Jacobsen; Kristina Myrvold (2012). Sikhs Across Borders: Transnational Practices of European Sikhs. A&C Black. pp. 232–235. ISBN 978-1-4411-1387-0.

- Robin Rinehart (2014). Pashaura Singh and Louis E Fenech (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Sikh Studies. Oxford University Press. pp. 137–138. ISBN 978-0-19-969930-8.

- Robin Rinehart (2014). Pashaura Singh and Louis E Fenech (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Sikh Studies. Oxford University Press. pp. 138–139. ISBN 978-0-19-969930-8.

- Robin Rinehart (2014). Pashaura Singh and Louis E Fenech (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Sikh Studies. Oxford University Press. p. 139. ISBN 978-0-19-969930-8.

- Robin Rinehart (2014). Pashaura Singh and Louis E Fenech (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Sikh Studies. Oxford University Press. p. 140. ISBN 978-0-19-969930-8.

- Teja Singh; Ganda Singh (1989). A Short History of the Sikhs: 1469-1765. Publication Bureau, Punjabi University. pp. 61–66 with footnotes. ISBN 978-81-7380-007-8.

- Mohinder Singh; Ganda Singh. History and Culture of Panjab. Atlantic Publishers. pp. 43–44.

- Harjot Oberoi (1994). The Construction of Religious Boundaries: Culture, Identity, and Diversity in the Sikh Tradition. University of Chicago Press. pp. 99–102. ISBN 978-0-226-61593-6.

- Surinder Singh Kohli (2005). The Dasam Granth. Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers. pp. xxxv, 461–467. ISBN 978-81-215-1044-8.

- Robin Rinehart (2014). Pashaura Singh and Louis E Fenech (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Sikh Studies. Oxford University Press. p. 141. ISBN 978-0-19-969930-8.

- Robin Rinehart (2014). Pashaura Singh and Louis E Fenech (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Sikh Studies. Oxford University Press. pp. 141–142. ISBN 978-0-19-969930-8.

- Robin Rinehart (2014). Pashaura Singh and Louis E Fenech (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Sikh Studies. Oxford University Press. pp. 144–145. ISBN 978-0-19-969930-8.

- Britannica, Inc Encyclopaedia (2009). Encyclopedia of World Religions. Encyclopædia Britannica. p. 279. ISBN 978-1-59339-491-2.

- Robin Rinehart (2014). Pashaura Singh and Louis E Fenech (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Sikh Studies. Oxford University Press. pp. 142–143. ISBN 978-0-19-969930-8.

- Page 133, Sikhs in the Diaspora, Surinder Singh bakhshi, Dr Surinder Bakhshi, 2009

- The Japu, the Jaapu and the Ten Sawayyas (Quartets) – beginning "Sarwag sudh"-- in the morning.: Chapter III, Article IV, Sikh Rehat Maryada

- iii) the Sawayya beginning with the words "pae gahe jab te tumre": Article IV, Chapter III, Sikh Rehat Maryada

- Gerald Parsons (2012). The Growth of Religious Diversity - Vol 1: Britain from 1945 Volume 1: Traditions. Routledge. pp. 221–222. ISBN 978-1-135-08895-8.

- Editors of Encyclopedia Britannica (2019). "Namdhari (Sikh sect)". Encyclopædia Britannica.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Wendy Doniger; Encyclopaedia Britannica staff (1999). Merriam-Webster's Encyclopedia of World Religions. Merriam-Webster. p. 279. ISBN 978-0-87779-044-0.

- Giani Kirpal Singh (samp.), Sri Gur Panth Parkash, Vol. 3 (Amritsar: Manmohan Singh Brar, 1973), pp. 1678–80, verses 61-62

- Mansukhani, Gobind Singh (1993). Hymns from the Dasam Granth. Hemkunt Press. p. 10. ISBN 978-81-7010-180-2.

- Robin Rinehart (2011). Debating the Dasam Granth. Oxford University Press. pp. 43–46. ISBN 978-0-19-984247-6.

External links

- Debating the Dasam Granth, Christopher Shackle (2012)

- Framing the Dasam Granth Debate: Throwing the Baby with the Bath Water, Pashaura Singh (2015)

- Presence and Absence: Constructions of Gender in Dasam Granth Exegesis, Robin Rinehart (2019)