Patsey

Patsey was an African-American slave who lived in the mid 19th century. Another slave, Solomon Northup (who was later freed), wrote about her in his book Twelve Years a Slave. The book was later adapted into a film, in which she was portrayed by Lupita Nyong'o, who won the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actress for her performance.

Patsey | |

|---|---|

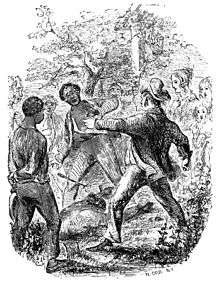

sketch from Solomon Northup's book The staking out and flogging of the girl named Patsey | |

| Born | around 1830 |

| Died | after 1863 |

| Known for | Twelve Years a Slave |

Life

In the book, Northup writes that Patsey's mother was from Guinea, enslaved and taken to Cuba. Her mother was then sold to a family named Buford in the Southern region of the United States. Patsey is believed to have been born around 1830, in South Carolina. The earliest record of Patsey as a slave is in 1843, when she was 13. She was sold to a man named Edwin Epps in Louisiana.[1]

Solomon Northup and Patsey became friends after he arrived on the Epps plantation. Northup wrote in his book that Patsey was the queen of the fields on the plantation and was often praised by her owner for her ability to pick large amounts of cotton. Northup also wrote that Patsey was unlike the other slaves and had a sense of spirit that was unwavering in its strength.[2] Epps's wife Mary became jealous when Epps started raping Patsey, who would have been under the age of 18 when he began assaulting her. Mary demanded her husband sell Patsey, but he refused to do so, as detailed by Northup in the book, and Mary also began to physically abuse Patsey. In his book, Northup wrote that Mary tried to bribe other workers and slaves to kill Patsey and dump her body in the swamps, but no one would. Even though Patsey was a highly productive slave and a favorite of Epps, she was not given special treatment.

Though Northup described Patsey as "a joyous creature, a laughing, light-hearted girl,"[3] the intense brutality she suffered, caught between "a licentious master and a jealous mistress" drove her wish for death.[4] Yet Patsey, like Northup, also dreamed fervently of freedom.[5]

Abuse

Patsey was often whipped and had many scars on her back. Northup wrote that on one occasion she was scourged to the point of near death because she had gone to a neighboring plantation for a bar of soap. When Epps found out she had left his plantation, he had her tied to a stake and ordered Solomon to whip her. After hearing the mistress whispering in his ear to discipline her, Epps then took the whip himself until, as described in Northup's book, she was "literally flayed" from over 50 lashes. He wrote that after this experience he and Patsey were severely traumatized and that he had never forgotten what Patsey endured during the time he knew her.[6]

Later life

In Twelve Years a Slave Northup wrote that as he was about to leave the Epps plantation in 1853 after having been there with Patsey for almost a decade:

"Patsey ran from behind a cabin and threw her arms about my neck. 'Oh! Platt [the name given to Northup by his kidnappers],' she cried, tears streaming down her face, 'you're goin' to be free—you're goin' way off yonder where we'll neber see ye any more. You've saved me a good many whipping, Platt; I'm glad you're goin' to be free—but oh! de Lord, de Lord! what'll become of me?" Northup then boarded a carriage to freedom and he never saw her again.[7]

Writer Katie Calautti chronicled her search for what became of Patsey in a 2014 Vanity Fair article.[8] Though little is known about Patsey after Northup's departure, a comment in the Vanity Fair article (since removed) revealed a link proving she did survive until at least 1863, ten years after Solomon was freed. In a letter printed in a New York state newspaper, the Mexico Independent, on June 18, 1863, Capt. Henry C. Devendorf, a Union officer from upstate New York, told how he encountered a slave named Bob near Bayou Boeuf. Bob was one of Epps' slaves, and the New York soldiers had a chance to converse with him, and confirmed that Epps was his master, and that he had known Northup. "Patsy," wrote Devendorf in the letter (written in May 1863), "went away with our army last week, so she is at last far from the caprices of her jealous mistress." (The issue of the Mexico Independent that has Devendorf's letter is available as part of an online collection of New York State historical newspapers.[9] The part of the letter that references Northup and the Epps plantation is summarized by Northup researcher David Fiske).[10]

With renewed interest in her after the 2013 film 12 Years a Slave won the Academy Award for Best Picture, historians continue to research in hopes of pinpointing more specifically what happened to her.[11]

See also

References

- Rosenberg, Alyssa (4 March 2014). "What Happened To Solmon Northup And Patsey After The Events Of '12 Years A Slave'?". Thinking Progress. Retrieved 20 September 2014.

- "12 Years a Slave: History vs Hollywood". History vs. Hollywood. 2013. Retrieved 20 September 2014.

- Northup 1853, p. 140.

- Northup 1853, p. 141.

- Northup 1853, p. 191.

- Sorkin, Amy Davidson (5 November 2013). ""Jezebel" and Solomon: Why Patsey Is the Hero of "12 Years a Slave"". The New Yorker. Condé Nast. Retrieved 20 September 2014.

- Northup 1853.

- Calautti, Katie (2 March 2014). ""What'll Become of Me?" Finding the Real Patsey of 12 Years a Slave". Vanity Fair. Condé Nast. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- Mexico Independent. 18 June 1863. p. 3 http://nyshistoricnewspapers.org/lccn/sn83031559/1863-06-18/ed-1/seq-3/. Retrieved 21 September 2014 – via NyS Historic Newspapers. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Fiske, David (2012). "Seeking Patsey's Fate". Hike Ghost Towns. Retrieved 21 September 2014.

- Ball, Charing (25 October 2013). ""12 Years A Slave," The Character Of Patsey, And Why I Wish Death To The Term "Negro Bed Wench"". MadameNoire. Retrieved 20 September 2014.

Bibliography

- Fiske, David; Brown, Clifford W. & Seligman, Rachel (2013). Solomon Northup: The Complete Story of the Author of Twelve Years a Slave.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link), a complete biography of Northup

- Northup, Solomon (1853). Twelve Years a Slave: Narrative of Solomon Northup, a citizen of New York, kidnapped in Washington city in 1841, and rescued in 1853, from a cotton plantation near the Red River in Louisiana. Derby & Miller. p. 362. ISBN 978-1-84391-471-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)