Omar ibn Said

Omar ibn Said (Arabic: عمر بن سيد 'Umar bin Sa'iid; 1770–1864) was a writer and Islamic scholar, born and educated in what is now Senegal in West Africa, who was enslaved and transported to the United States in 1807. There, while enslaved for the remainder of his life, he wrote a series of works of history and theology, including a posthumously famous autobiography.

Omar Ibn Said | |

|---|---|

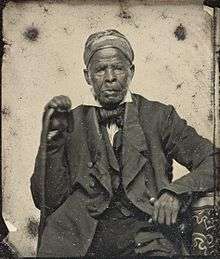

Omar ibn Said, c. 1850 | |

| Born | Omar ibn Sayyid 1770 |

| Died | 1864 (aged 94) |

| Nationality | Senegalese; African American |

| Other names | Uncle Moreau, Prince Omeroh |

| Education | Formal Islamic education in Senegal |

| Known for | Islamic Scholar, author of Slave narratives |

Biography

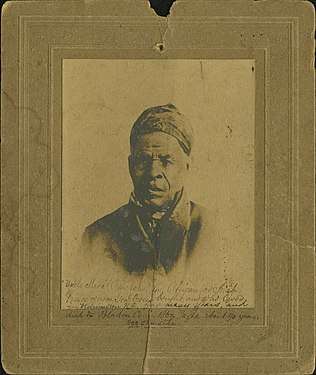

Omar ibn Said was born in present-day Senegal in Futa Toro,[1] a region along the Middle Senegal River in West Africa, to a wealthy family.[2] He was an Islamic scholar and a Fula who spent 25 years of his life studying with prominent Muslim scholars, learning subjects ranging from arithmetic to theology in Africa. In 1807, he was captured during a military conflict, enslaved and taken across the Atlantic Ocean to the United States. He escaped from a cruel master in Charleston, South Carolina, and journeyed to Fayetteville, North Carolina. There he was recaptured and later sold to James Owen. Said lived into his mid-nineties and was still enslaved at the time of his death in 1864. He was buried in Bladen County, North Carolina. Omar ibn Sa'id was also known as Uncle Moreau and Prince Omeroh.[1]

Although Omar was converted to Christianity on December 3, 1820, there are dedications to Muhammad written in his Bible, and a card dated 1857 on which he wrote Surat An-Nasr, a short sura which refers to the conversion of non-Muslims to Islam 'in multitudes.' The back of this card contains another person's handwriting in English misidentifying the sura as the Lord's Prayer and attesting to Omar's status as a good Christian.[3] Additionally, while others writing on Omar's behalf identified him as a Christian, his own autobiography and other writings offer more of an ambiguous position. In the autobiography, he still offers praise to Muhammad when describing his life in his own country; his references to "Jesus the Messiah" in fact parallel Quranic descriptions of Jesus (who is called المسيح 'the Messiah' a total of eleven times in the Quran), and descriptions of Jesus as 'our lord/master' (سيدنا sayyidunā) employ the typical Islamic honorific for prophets and is not to be confused with Lord (ربّ rabb); and description of Jesus as 'bringing grace and truth' (a reference to John 1:14) is equally appropriate to the conception of Jesus in Islam.

Literary analysis of Said’s autobiography suggests that he wrote it for two audiences, the white literates who sought to exploit his conversion to Christianity and Muslim readers who would recognize Qur'anic literary devices and subtext and understand his position as a fellow Muslim living under persecution. In a letter written to Sheikh Hunter regarding the autobiography, he apologized for forgetting the "talk" of his homeland and ended the letter saying: "O my brothers, do not blame me," with the knowledge that Hunter would require Arabic-speaking translators to read the message. Scholar Basima Kamel Shaheen argues that Said’s spiritual ambiguity may have been purposefully cultivated to impress upon a wide readership the injustices of slavery.[4]

Manuscripts

.jpg)

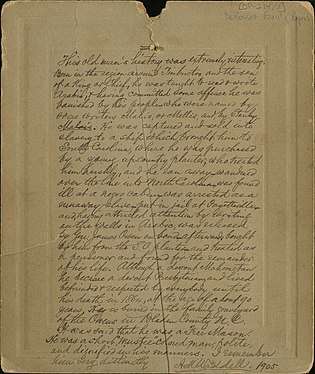

Omar ibn Said is widely known for fourteen manuscripts that he wrote in Arabic. Out of all of his Arabic manuscripts, he is best known for his autobiographical essay, The Life of Omar Ibn Said, written in 1831.[5] It describes some of the events of his life and includes reflections on his steadfast adherence to Islam and his openness towards other "God-fearing" people. On the surface, the document may appear to be tolerant towards slavery; however, Said begins it with Surat Al-Mulk, a chapter from the Qur'an, which states that only God has sovereignty over human beings.[6] The manuscript is the only known Arabic autobiography by a slave in America. It was sold within a collection of Sa'id's documents between private collectors prior to its acquisition by the Library of Congress in 2017. It has since been treated for preservation and made viewable online.[7]

Most of Said's other work consisted of Islamic manuscripts in Arabic, including a handwritten copy of some short chapters (surat) from the Qur'an that are now part of the North Carolina Collection in the Wilson Library at University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Transcribing from memory, ibn Said made some mistakes in his work, notably at the start of Surat An-Nasr. His Bible, a translation into Arabic published by a missionary society, which has notations in Arabic by Omar, is part of the rare books collection at Davidson College.[8] Sa'id was also the author of a letter, dated 1819, addressed to James Owen's brother, Major John Owen, written in Arabic and containing numerous Quranic references (including from the above-mentioned Surat Al-Mulk), which also includes several geometric symbols and shapes which point to its possible esoteric intentions.[9] This letter, currently housed in Andover Theological Seminary, is reprinted in Allen Austin's African Muslims in Antebellum America: A Sourcebook.

Legacy

In 1991, a mosque in Fayetteville, North Carolina renamed itself Masjid Omar ibn Sayyid in his honor.[10]

Gallery

Ambrotype portrait, c. 1855

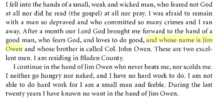

Ambrotype portrait, c. 1855 Photographic portrait, c. 1905

Photographic portrait, c. 1905 reverse of c. 1905 portrait.

reverse of c. 1905 portrait.

See also

- Islam in the United States

- List of slaves

Further reading

- Muhammed Al-Ahari Five Classic Muslim Slave Narratives (Chicago: Magribine Press, 2006). ISBN 978-1-4635-9327-8.

- A Muslim American Slave: The Life of Omar Ibn Said, ed. and translated by Ala Alryyes (University of Wisconsin Press, 2011).

- Allan D. Austin, African Muslims in Antebellum America: A Sourcebook (New York: Garland Publishers, 1984).

- Thomas C. Parramore, "Muslim Slave Aristocrats in North Carolina," North Carolina Historical Review Vol. 77 No. 2 (April 2000): pp 127–150.

References

- Omar ibn Said (1831). "Autobiography of Omar ibn Sa'id, Slave in North Carolina, 1831". University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

- Powell, William S. (1979). "Omar ibn Said, b. 1770?". Dictionary of North Carolina Biography. University of North Carolina Press.

- Horn, Patrick E. "Omar ibn Sa'id, African Muslim Enslaved in the Carolinas". University Library, University of North Carolina.

- Shaheen, Basima Kamel. (2014) "Literary Form and Islamic Identity in The Life of Omar Ibn Said" in Journeys of the Slave Narrative in the Early Americas edited by Nicole N. Aljoe and Ian Finseth, 187-208. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press.

- Jonathan Curiel. Al'America. pp.30-32.

- "Al-Quran Surah 67. Al-Mulk, Ayah 1". Alim - Islamic Software for Quran and Hadith. Retrieved 2019-04-30.

- "Only Known Surviving Muslim American Slave Autobiography Goes Online at the Library of Congress". Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Retrieved 2019-01-18.

- Davidson College Archives Omar Ibn Sayyid

- Hunwick, John O. (2004). "I Wish to be Seen in Our Land Called Afrika: Umar b. Sayyid's Appeal to be Released from Slavery (1819)" (PDF). Journal of Arabic and Islamic Studies 5.

- Omar ibn Said Archived 2008-05-16 at the Wayback Machine Davidson Encyclopedia Tammy Ivins, June 2007

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Omar Ibn Said. |