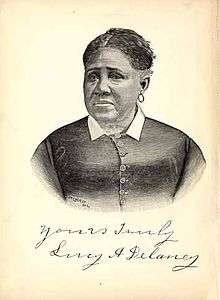

Lucy Delaney

Lucy Ann Delaney, born Lucy Berry (c. 1830 – after 1891), was an African-American author, former slave, and activist, notable for her 1891 narrative From the Darkness Cometh the Light, or, Struggles for Freedom. This is the only first-person account of a "freedom suit" and one of the few post-Emancipation published slave narratives.

Lucy Ann Delaney | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Lucy Berry c. 1830 St. Louis, Missouri, U.S. |

| Died | after 1891 |

| Occupation | author, activist |

| Language | English |

| Nationality | American |

| Notable works | From the Darkness Cometh the Light, or, Struggles for Freedom |

| Spouse | Frederick Turner ( m. 1845)Zachariah Delaney ( m. 1849) |

The memoir recounts her mother Polly Berry's legal battles in St. Louis, Missouri, for her own and her daughter's freedom from slavery. For her daughter's case, Berry attracted the support of Edward Bates, a prominent Whig politician and judge, and the future US Attorney General under President Abraham Lincoln. He argued the case of Lucy Ann Berry in court and won in February 1844. Their cases were two of 301 freedom suits filed in St. Louis from 1814 to 1860. Discovered in the late twentieth century, the case files are held by the Missouri Historical Society and searchable online.

Early life

For decades little was known of Lucy Ann Delaney beyond her memoir, but in the late twentieth century, both her and her mother's suits were discovered among case files for 301 freedom suits in St. Louis from 1814–1860. Related material is available online in a searchable database created by the St. Louis Circuit Court Historical Project, in collaboration with Washington University.[1] In addition, scholars have done research into censuses and other historic material related to Delaney's memoir to document the facts.

Born into slavery in St. Louis, Missouri in 1830, Lucy Ann Berry was the daughter of slaves Polly Berry (born Polly Crocket) and a mulatto father whose name she did not note. They also had a second daughter, Nancy. Polly Crocket and Lucy's father were slaves owned by Major Taylor Berry and his wife, Frances.[2] Lucy said that Polly Berry had been born free in Illinois, but was kidnapped when a child by slave catchers and sold into slavery in Missouri.[3] (In her freedom suit, Polly Berry deposed that she was held as a slave in Wayne County, Kentucky by Joseph Crockett, and was brought by him to Illinois. There they stayed for several weeks while he hired her out for domestic work. As Illinois was a free state, he was supposed to lose his right to hold slave property by staying there, and Polly could have been freed. It was on this basis that she was later awarded freedom, as witnesses were found to testify as to her having been held illegally as a slave in Illinois.[4]

When Delaney wrote her memoir late in life, she remembered the Major and his wife Fanny Berry as kind slaveholders. The major told Polly and her husband that his slaves would be freed upon his death and the death of his wife.[2] After the major died in a duel, Fanny Berry married Robert Wash, a lawyer later appointed as a Missouri State Supreme Court judge. When Fanny Wash died, the Berry slave family's fortunes changed. Judge Wash sold Lucy Ann's father to a plantation down the Mississippi River in the Deep South.[3]

Polly Berry became concerned for the safety of her daughters, and determined they should escape. Lucy Ann's older sister Nancy slipped away while traveling with a daughter of the family, Mary Berry Cox, and her new husband on their honeymoon in the North. Nancy left them at Niagara Falls, took the ferry across the river, and safely reached Canada and a friend of her mother's.[3]

After having conflict with Mary Cox in 1839, Polly Berry was sold to Joseph A. Magehan, but escaped about three weeks later.[5] She made it to Chicago, but was captured by slave catchers. They returned her to Magehan and slavery in St. Louis.[3]

On returning, Polly Berry (also known as Polly Wash after her previous master) sued for her freedom in the Circuit Court in the case known as Polly Wash v. Joseph A. Magehan in October 1839.[5] When her suit was finally heard in 1843, her attorney Harris Sproat was able to convince a jury of her free birth and kidnapping as a child. Wash was freed. She remained in St. Louis to continue her separate effort to secure her daughter Lucy Ann Berry's freedom, for which she had filed suit in 1842, shortly after Berry fled her master.[5]

Trial and freedom

By 1842, Lucy Ann was working for Martha Berry Mitchell, another of the Berry daughters. They had conflict in part because of the slave girl's inexperience at heavy domestic tasks, including laundry. Martha decided to sell her, and her husband David D. Mitchell arranged the sale.[5] The day before she was to leave, Lucy Ann escaped and hid at the house of a friend of her mother's.

That week, Polly Wash filed suit in Circuit Court in St. Louis for Lucy Ann Berry's freedom, as a "next friend" to the minor girl.[5] Since her own case had not been settled, Wash was still considered a slave with no legal standing, but under the slave law, she could bring suit on behalf of a minor. The law provided a slave with the status of a "poor person", with court-appointed counsel when the court determined the case had grounds. Delaney's memoir suggests that her mother's attorneys suggested her strategy of filing separate suits for her and her daughter, to prevent a jury's worrying about taking too much property from one slaveholder.[6]

The case was prepared primarily by Francis Butter Murdoch, who litigated nearly one third of the freedom suits filed in St. Louis from 1840–1847.[5] Francis B. Murdoch had served as the Alton, Illinois district attorney, and prosecuted the murder of the printer Elijah Lovejoy by anti-abolitionists.[7] Wash also attracted the support of Edward Bates; a prominent Whig politician and judge, he argued Lucy Ann's case in court. Bates later served as the US Attorney General under President Abraham Lincoln.

While waiting for trial, Lucy Ann Berry was remanded to the jail, where she was held for more than 17 months without being hired out, which was customary to offset expenses and earn money for slaves' masters. In February 1844 the case went to trial.[5] By then her mother's case had been settled, and Polly Wash was declared free. In addition, Wash had affidavits from people who knew her and her daughter. Judge Robert Wash (Fanny Berry Wash's widower and Polly's previous master) testified that Lucy Ann was definitely Polly Berry Wash's child. The jury believed the case for freedom had been proved, and the judge announced Lucy Ann Berry was free.[5] She was approximately 14 years old.[3]

Lucy Ann and Polly Berry lived in St. Louis after gaining her freedom. They had to get certificates as free blacks and deal with other restrictions of the time. They worked together as seamstresses.

Marriage and family

In 1845, Lucy Ann met and married steamboat worker Frederick Turner, with whom she settled in Quincy, Illinois, and her mother lived with them. Turner died soon after in a boiler explosion on the steamboat The Edward Bates. (It was named for the lawyer who had helped secure Lucy Ann's freedom two years before.)[3]

Polly Wash and Lucy Ann moved back to St. Louis. In 1849, Lucy Ann met and married Zachariah Delaney. They were married for the rest of their lives, and her mother lived with them. Though the couple had four children, two did not survive infancy; the remaining children, a son and a daughter, both died in their early twenties.[3]

Later life

As Delaney recounted in her memoir, she became active in civic and religious associations. Such organizations grew rapidly in both the African-American and white communities nationally in the years following the Civil War. She joined the African Methodist Episcopal Church in 1855, founded in 1816 in Philadelphia as the first independent black denomination in the US. In addition, Delaney was elected president of the Female Union, an organization of African-American women. She also served as president of the Daughters of Zion, as well as a women's group affiliated with the Freemasons, to which her husband belonged.[3] They often supported community education and health projects.

Delaney belonged to the Col. Shaw Woman's Relief Corps, No. 34, a women's auxiliary to the Col. Shaw Post, 343, Grand Army of the Republic (GAR). The veterans' group was named after the white commanding officer of the 54th Massachusetts Infantry, the first of the United States Colored Troops and a unit that achieved renown for courage in the Civil War. Delaney dedicated her memoir to the GAR, which had fought for the freedom of slaves.[3]

In the late nineteenth century, many blacks migrated to St. Louis from the Deep South for its industrial jobs. Delaney met with new arrivals to try to track down her father. Learning that he was living on a plantation 15 miles south of Vicksburg, Mississippi, she wrote and asked him to visit her. Her sister Nancy from Canada joined their reunion in St. Louis. Their father was glad to see them, but, with his wife Polly dead by then, he returned to Mississippi and his friends of 45 years.[3]

Nothing was recorded about the year or circumstances of Lucy Delaney's death.

Memoir

In 1891, Delaney published her From the Darkness Cometh the Light, or, Struggles for Freedom, the only first-person account of a freedom suit.[5] The text is also a slave narrative, most of which were published prior to the Civil War and Emancipation.[4] Delaney devoted most of her account to her mother Polly Berry's struggles to free her family from slavery. Though the story is Delaney's, she features her mother as the lead protagonist.

The narrative is steeped in spirituality. It celebrated what Delaney saw as God's benevolent role in her own life and she attacked the hypocrisy of Christian slave owners. From the Darkness shows the strength of the African Americans who suffered under slavery, rather than recount the horrors of the institution. By continuing her memoir after her gaining freedom at the age of 14, Delaney showed her fortitude following the death of her first husband, and later the deaths of each of her four children. She portrayed her mother Polly Berry as serving as an adviser and role model. By celebrating her own political and civic activities, Delaney argued for the place of African Americans in US democracy.

Publication history

From the Darkness was originally published in St. Louis in 1891 by J.T. Smith. After the rise of the 20th-century Civil Rights Movement and feminism, and new interest in historic black and women's literature, in 1988 the book was reprinted in the collection Six Women's Slave Narratives by Oxford University Press. It is carried online by Project Gutenberg, as well as by the University of North Carolina in its Documents of the American South .

The literary critic P. Gabrielle Foreman has suggested that the author Frances Harper based her character of "Lucille Delaney" in the novel Iola Leroy (1892) on the historic Delaney's memoir published the year before.

Work

- From the Darkness Cometh the Light, or, Struggles for Freedom (1891), reprinted in Six Women's Slave Narratives, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988. ISBN 0-19-505262-5.

See also

- Charlotte Dupuy

- Dred Scott

- Marguerite Scypion

- List of slaves

Citations

- "History of Freedom Suits in Missouri" Archived December 13, 2018, at the Wayback Machine, St. Louis Circuit Court Historical Records Project, September 1, 2004, accessed January 4, 2011.

- Van Ravenswaay, Charles (1991). St. Louis: An Informal History of the City and Its People, 1764-1865. St. Louis, MO: Missouri History Museum.

- Lucy A. Delaney, From the Darkness Cometh the Light: or Struggles for Freedom, Electronic edition, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 2001; accessed April 22, 2009.

- Edlie L. Wong (July 1, 2009). Neither Fugitive nor Free: Atlantic Slavery, Freedom Suits, and the Legal Culture of Travel. New York University Press. pp. 127–. ISBN 978-0-8147-9465-4.

- Eric Gardner, " 'You have no business to whip me': the freedom suits of Polly Wash and Lucy Ann Delaney", African American Review, Spring 2007, accessed January 4, 2011.

- Wong, p. 135.

- Wong, p. 132.

References

- Ann Allen Shockley, Afro-American Women Writers 1746–1933: An Anthology and Critical Guide, New Haven, Connecticut: Meridian Books, 1989. ISBN 0-452-00981-2

- Jeannine Delombard, Slavery On Trial: Law, Abolitionism, and Print Culture (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2007).

External links

- Works by Lucy Delaney at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Lucy Delaney at Internet Archive

- Works by Lucy Delaney at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- "Freedom Suits", African-American Life in St. Louis, 1804–1865, from the Records of the St. Louis Courts, Jefferson National Expansion Memorial, National Park Service

- From the Darkness Cometh the Light or Struggles for Freedom, St. Louis, MO: J.T. Smith, [189-?]; Documenting the American South, University of North Carolina (full text)