Scania

Scania (Swedish: Skåne (Swedish: [ˈskôːnɛ] (![]()

Scania Skåne | |

|---|---|

Coat of arms | |

| |

| Country | Sweden |

| Land | Götaland |

| County | Skåne County |

| Area | |

| • Total | 10,939 km2 (4,224 sq mi) |

| Population (31 December 2016[2]) | |

| • Total | 1,322,193 |

| • Density | 120/km2 (310/sq mi) |

| Ethnicity | |

| • Language | Swedish |

| • Dialect | Scanian |

| Culture | |

| • Flower | Oxeye daisy |

| • Animal | Red deer |

| • Bird | Red kite |

| • Fish | Eel |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal codes | 20000-29999 |

| Area codes | 040–046 |

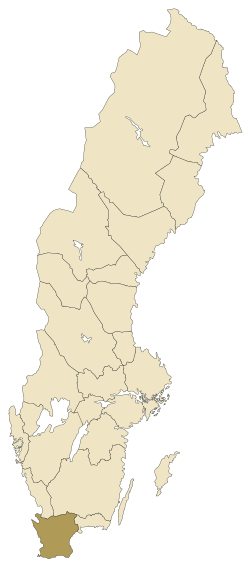

To the north, Scania borders the provinces of Halland and Småland, to the northeast Blekinge, to the east and south the Baltic Sea, and to the west Öresund. Since 2000, a road and railway bridge, the Øresund Bridge,[4] bridges the Sound to Denmark. Scania is part of the transnational Øresund Region.[5]

From north to south Scania is around 130 km and covers less than 3% of Sweden's total area. The population of over 1,320,000[6] represents 13% of the country's population. With 121 inh/km2 Scania is the second most densely populated province of Sweden.

Historically, Scania was part of the kingdom of Denmark, up until the Treaty of Roskilde in 1658.[7] Denmark regained control of the province during the Scanian War 1676–1679 and again briefly in 1711. Scania was formally included in Sweden in 1720.[8][9]

Name

Endonym and exonyms

The endonym used in Swedish and other North Germanic languages is Skåne (formerly spelled Skaane in Danish and Norwegian). The Latinized form Scania occurs especially in British English as an exonym.[10] However, sometimes the endonym Skåne is used in English text, such as in tourist information,[11] even sometimes as Skane with the diacritic omitted, which is wrong both in Swedish and English.[12][13] Scania is the only Swedish province for which exonyms are still widely used in many languages, e.g. French Scanie, Dutch and German Schonen, Polish Skania, Spanish Escania, Italian Scania, etc. For the province's modern administrative counterpart, Skåne län, the endonym Skåne is used in English.[14]

In the Alfredian translation of Orosius's and Wulfstan's travel accounts, the Old English form Sconeg appears.[15][16] Frankish sources mention a place called Sconaowe; Æthelweard, an Anglo-Saxon historian, wrote about Scani;[17] and in Beowulf's fictional account, the names Scedenige and Scedeland appear as names for what is a Danish land.[15]

Etymology

The names Scania and Scandinavia are considered to have the same etymology[18][19][20][21] and the southernmost tip of what is today Sweden was called Scania by the Romans and thought to be an island. The actual etymology of the word remains dubious and has long been a matter of debate among scholars. The name is possibly derived from the Germanic root *Skaðin-awjã, which appears in Old Norse as Skáney.[22] According to some scholars, the Germanic stem can be reconstructed as *Skaðan- meaning "danger" or "damage" (English scathing, German Schaden, Swedish skada).[23] Skanör in Scania, with its long Falsterbo reef, has the same stem (skan) combined with -ör, which means "sandbanks".

Administration

Between 1719 and 1996, the province was subdivided in two administrative counties (län), Kristianstad County and Malmöhus County, each under a governor (landshövding) appointed by the central government of Sweden.

When the first local government acts took effect in 1863, each county also got an elected county council (landsting). The counties were further divided into municipalities.

The local government reform of 1952 reduced the number of municipalities, and a second subdivision reform, carried out between 1968 and 1974, established today's 33 municipalities[24] (Swedish: kommuner) in Scania. The municipalities have municipal governments, similar to city commissions, and are further divided into parishes (församlingar). The parishes are primarily entities of the Church of Sweden, but they also serve as a divisioning measure for the Swedish population registration and other statistical uses.

In 1999, the county council areas were amalgamated, forming Skåne Regional Council (Region Skåne), responsible mainly for public healthcare, public transport and regional planning and culture.

Heraldry

During the Danish era, the province had no coat of arms. In Sweden, however, every province had been represented by heraldic arms since 1560.[25] When Charles X Gustav of Sweden suddenly died in 1660 a coat of arms had to be created for the newly acquired province, as each province was to be represented by its arms at his royal funeral. After an initiative from Baron Gustaf Bonde, the Lord High Treasurer of Sweden, the coat of arms of the City of Malmö was used as a base for the new provincial arms. The Malmö coat of arms had been granted in 1437, during the Kalmar Union, by Eric of Pomerania and contains a Pomeranian griffin's head. To distinguish it from the city's coat of arms the tinctures were changed and the official blazon for the provincial arms is, in English: Or, a griffin's head erased gules, crowned azure and armed azure, when it should be armed.

The province was divided in two administrative counties 1719–1996. Coats of arms were created for these entities, also using the griffin motif. The new Skåne County, operative from 1 January 1997, got a coat of arms that is the same as the province's, but with reversed tinctures. When the county arms is shown with a Swedish royal crown, it represents the County Administrative Board, which is the regional presence of central government authority. In 1999 the two county councils (landsting) were amalgamated forming Region Skåne. It is the only one of its kind using a heraldic coat of arms. It is also the same as the province's and the county's, but with a golden griffin's head on a blue shield.[26] The 33 municipalities within the county also have coats of arms.

The Scania Griffin has become a well-known symbol for the province and is also used by commercial enterprises. It is, for instance, included in the logotypes of the automotive manufacturer Scania AB and the airline Malmö Aviation.

Coat of arms:

City of Malmö (1437)

City of Malmö (1437) City of Malmö

City of Malmö

(revised 1974) Skåne

Skåne

(1660, revised 1939)

Kristianstad County

Kristianstad County

(revised 1939) Malmöhus County

Malmöhus County

(revised 1939) Skåne County

Skåne County

(1997)

History

Scania was first mentioned in written texts in the 9th century. It came under Danish king Harald Bluetooth in the middle of the 10th century. It was then a region that included Blekinge and Halland, situated on the Scandinavian Peninsula and formed the eastern part of the kingdom of Denmark. This geographical position made it the focal point of the frequent Dano-Swedish wars for hundreds of years.

By the Treaty of Roskilde in 1658, all Danish lands east of Øresund were ceded to the Swedish Crown. First placed under a Governor-General, the province was eventually integrated into the kingdom of Sweden. The last Danish attempt to regain its lost provinces failed after the 1710 Battle of Helsingborg.

In 1719, the province was subdivided in two counties and administered in the same way as the rest of Sweden. Scania has since that year been fully integrated in the Swedish nation. In the following summer, July 1720, the last peace treaty between Sweden and Denmark was signed.[27][28]

On 28 November 2017 it was ruled that the Scanian flag would become the official flag of Scania.[29][30]

Politics

During Sweden's financial crisis in the early and mid-1990s, Scania, Västra Götaland and Norrbotten were among the hardest hit in the country, with high unemployment rates as a result.[31] In response to the crisis, the County Governors were given a task by the government in September 1996 to co-ordinate various measures in the counties to increase economic growth and employment by bringing in regional actors.[31] The first proposal for regional autonomy and a regional parliament had been introduced by the Social Democratic Party's local districts in Scania and Västra Götaland already in 1993. When Sweden joined the European Union two years later, the concept "Regions of Europe" came in focus and a more regionalist-friendly approach was adopted in national politics.[32] These factors contributed to the subsequent transformation of Skåne County into one of the first "trial regions" in Sweden in 1999, established as the country's first "regional experiment".[32]

The relatively strong regional identity in Scania is often referred to in order to explain the general support in the province for the decentralization efforts introduced by the Swedish government.[33] On the basis of large scale interview investigations about Region Skåne in Scania, scholars have found that the prevailing trend among the inhabitants of Scania is to "[look] upon their region with more positive eyes and a firm reliance that it would deliver the goods in terms of increased democracy and constructive results out of economic planning".[34]

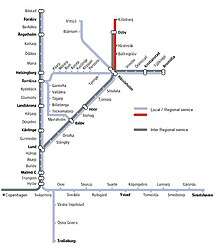

Communications

Just as five Scanian stations are served partly (Hässleholm and Osby) or entirely (Ballingslöv, Hästveda and Killeberg) by Småland local trains, the Scanian Pågatåg trains serve Markaryd in Småland.[35]

There are basically three ticket systems, one for internal Scanian travel, one for travel between Scania and Copenhagen and its surroundings and one for the Swedish national SJ-tickets for longer trips to the north. If traveling by railway towards the south, it's best to either use a travel agency or to purchase the ticket at Copenhagen Main Station (København H). An exception is if traveling to Berlin by night train and on the train ferry route between Trelleborg and Sassnitz. Unfortunately the current operator, Swedish Snälltåget, only uses this classic route during the summer (while many visitors believe Berlin to be best during spring and autumn).

Electrified dual track railroad exists from the border with Denmark at the Øresund Bridge to Lund, where it splits into two directions.[36] The dual tracks going towards Gothenburg end at Helsingborg,[37] while the other branch continues beyond the provincial border to neighbouring Småland, close to Killeberg.[38][36] This latter dual track continues to mid-Sweden.[36] There are also a few single track railroads.[36]

The E6 motorway is the main artery through the western part of Scania all the way from Trelleborg to the provincial border towards neighbouring Halland. It continues along the Swedish west coast to Gothenburg and most of the way to the Norwegian border. There are also several other motorways, especially around Malmö. Since 2000, the economic focus of the region has changed, with the opening of a road link across the Øresund Bridge to Denmark.[39]

The car ferry service between Helsingborg and Helsingør has 70 departures in each direction daily as of 2014.[40]

There are three minor airports in Sturup, Ängelholm and Kristianstad. The nearby Copenhagen Airport, which is the largest international airport in the Nordic countries, also serves the province.[41]

Geography and environmental factors

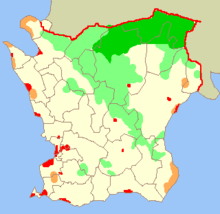

Unlike some regions of Sweden, the Scanian landscape is generally not mountainous, though a few examples of uncovered cliffs can be found at Hovs Hallar, at Kullaberg, and on the island Hallands Väderö. With the exception of the lake-rich and densely forested northern parts (Göinge), the rolling hills in the north-west (the Bjäre and Kulla peninsulas) and the beech-wood-clad areas extending from the slopes of the horsts, a sizeable portion of Scania's terrain consists of plains. Its low profile and open landscape distinguish Scania from most other geographical regions of Sweden which consist mainly of waterway-rich, cool, mixed coniferous forests, boreal taiga and alpine tundra.[42] The province has several lakes but there are relatively few compared to Småland, the province directly to the north. Stretching from the north-western to the south-eastern parts of Scania is a belt of deciduous forests following the Linderödsåsen ridge and previously marking the border between Malmöhus County and Kristianstad County. The much denser fir forests — typical of the greater part of Sweden — are only found in the north-eastern Göinge parts of Scania along the border with the forest-dominated province of Småland. While the landscape typically has a slightly sloping profile, in some places, such as north of Malmö, the terrain is almost completely flat.

The narrow lakes with a long north to south extent, which are very common further north, are lacking in Scania. The largest lake, Ivösjön in the north-east, has similarities with the lakes further north, but has a different shape. All other lakes tend to be round, oval or of more complex shape and also lack any specific cardinal direction. Ringsjön, in the middle of the province, is the largest of such lakes. In the winter, some smaller lakes east of Lund often attract young Eurasian sea eagles (Haliaeetus albicilla).

Where the sea meets higher parts of the sloping landscape, cliffs emerge. Such cliffs are white if the soil has a high content of chalk. Good examples of such coastlines exist at the southern side of Ven, between the towns of Helsingborg and Landskrona, and in parts of the south and south-east coasts. In other Swedish provinces, steep coastlines usually reveal primary rock instead.

The two major plains, Söderslätt in the south-west and Österlen in the south-east, consist of highly fertile agricultural land. The yield per unit area is higher than in any other region in Sweden. The Scanian plains are an important resource for Sweden since 25–95% of the total production of various types of cereals come from the region. Almost all Swedish sugar beet comes from Scania; the plant needs a long vegetation period. The same applies also to corn, pea and rape (grown for its oil), although these plants are less imperative in comparison with sugar beets.[43] The soil is among the most fertile in the world.

The Kullaberg Nature Preserve in northwest Scania is home to several rare species including spring vetchling, Lathyrus sphaericus.[44]

Geology and geomorphology

[T]he present landscape is a mosaic of landforms shaped during widely different ages.

The gross relief of Scania reflects more the preglacial development than the erosion and deposits caused by the Quaternary glaciers.[45] In Swedish the word ås commonly refers to eskers, but major landmarks in Scania, such as Söderåsen, are horsts[46] formed by tectonic inversion along the Sorgenfrei-Tornquist Zone in the late Cretaceous. The Scanian horsts run in a north-west to south-east direction, marking the southwest border of Fennoscandia.[47] Tectonic activity of the Sorgenfrei-Tornquist Zone during the break-up of Pangaea in the Jurassic and Cretaceous epochs led to the formation of hundreds of small volcanoes in central Scania.[48][49] Remnants of the volcanoes are still visible today.[48] Parallel with volcanism a hilly peneplain formed in northeastern Scania due to weathering and erosion of basement rocks.[50][51] The kaolinite formed by this weathering can be observed at Ivö Klack.[51] In the Campanian age of the Late Cretaceous a sea level rise led to the complete drowning of Scania. Subsequently, marine sediments buried old surfaces preserving the rocky shores and hilly terrain of the day.[51][52]

In the Paleogene period southern Sweden was at a lower position relative to sea level but was likely still above it as it was covered by sediments.[45][50] Rivers flowing over the South Småland peneplain flowed also across Scania which was at the time covered by thick sediments.[45] As the relative sea level sank and much of Scania lost its sedimentary cover antecedent rivers begun to incise the Söderåsen horst forming valleys.[45] During deglaciation these valleys likely evacuated large amounts of melt-water.[45] The relief of Scania's south-western landscape was formed by the accumulation of thick Quaternary sediments during the Quaternary glaciations.[47]

Vegetation and vegetation zones

The vast majority of Scania belongs to the European hardwood vegetation zone, a considerable part of which is now agricultural rather than the original forest. This zone covers Europe west of Poland and north of the Alps, and includes the British Isles, northern and central France and the countries and regions to the south and southeast of the North Sea up to Denmark. A smaller north-eastern part of Scania is part of the pinewood vegetation zone, in which spruce grows naturally. Within the larger part, pine may grow together with birch on sandy soil. The most common tree is beech. Other common trees are willow, oak, ash, alder and elm (which until the 1970s formed a few forests but now is heavily infected by the elm disease). Also rather southern trees like walnut tree, chestnut and hornbeam can be found. In parks horse chestnut, lime and maple are commonly planted as well. Common fruit trees planted in commercial orchards and private gardens include several varieties of apple, pear, cherry and plum; strawberries are commercially cultivated in many locations across the province. Examples of wild berries grown in domesticated form are blackberry, raspberry, cloudberry (in the north-east), blueberry, wild strawberry and loganberry.

National parks

Three of the 29 National parks of Sweden[53] are situated in Scania.

- Dalby Söderskog[54]

- Stenshuvud[55]

- Söderåsen[56]

Extremes

- Southernmost point: Smygehuk, Trelleborg Municipality, (55° 20' N) (also the southernmost point of Sweden)[57]

- Northernmost point: Gränsholmen, Osby Municipality

- Westernmost point: Kulla udd, Höganäs Municipality

- Easternmost point: Nyhult, Bromölla Municipality

- Highest point: Highest peak of Söderåsen, 212 metres

- Lowest spot: Kristianstad, −2.7 metres (also the lowest spot in all of Sweden)

- Largest lake: Ivösjön, 55 km2

- Largest island: Ven, 7.5 km2

Population

Scania is divided into 33 municipalities with population and land surface as the table below shows. There is a large population differency between the western Scania, that is located by, or close to Øresund sea compared to the middle and eastern parts of the province.

| Municipality | Population (April 2013) | Land area (km2) | Population density (/km2) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Municipalities that have a coast on Øresund or border a municipality that does (in yellow on the map) | |||

| Bjuv | 14,813 | 115.3 | 128.5 |

| Burlöv | 17,079 | 18.9 | 903.7 |

| Eslöv | 31,761 | 419.1 | 75.8 |

| Helsingborg | 132,254 | 344.0 | 384.4 |

| Höganäs | 24,986 | 150.8 | 165.7 |

| Kävlinge | 29,513 | 152.6 | 193.4 |

| Landskrona | 42,751 | 148.3 | 288.3 |

| Lomma | 22,415 | 55.6 | 403.1 |

| Lund | 118,542 | 448.5 | 264.3 |

| Malmö | 328,494 | 166,3 | 1975.2 |

| Staffanstorp | 22,572 | 106.8 | 211.3 |

| Svalöv | 13,217 | 387.3 | 34.1 |

| Svedala | 20,039 | 218.1 | 91.9 |

| Trelleborg | 42,744 | 339.9 | 125.8 |

| Vellinge | 33,725 | 142.6 | 236.5 |

| Åstorp | 14,849 | 92.2 | 161.0 |

| Ängelholm | 39,836 | 420.1 | 95.1 |

| Other municipalities (in white) | |||

| Bromölla | 12,314 | 162.5 | 74.4 |

| Båstad * | 14,224 | 209.8 | 67.8 |

| Hässleholm | 50,171 | 1268.5 | 39.6 |

| Hörby | 14,882 | 419.4 | 35.5 |

| Höör | 15,591 | 290.9 | 53.6 |

| Klippan | 16,741 | 374.3 | 44.7 |

| Kristianstad | 80,854 | 1246.3 | 64.9 |

| Osby | 12,704 | 576.2 | 22.0 |

| Perstorp | 7,089 | 158.8 | 44.6 |

| Simrishamn | 18,950 | 391.4 | 48.4 |

| Sjöbo | 18,359 | 492.2 | 37.3 |

| Skurup | 14,997 | 193.6 | 77.5 |

| Tomelilla | 12,913 | 395.9 | 32.6 |

| Ystad | 28,562 | 350.1 | 81.6 |

| Örkelljunga | 9,640 | 319.6 | 30.1 |

| Östra Göinge | 13,609 | 432.0 | 31.5 |

* A small part of Båstad municipality is located within the neighbouring province of Halland, this includes the village Östra Karup and some area around it, around 500 people lives in Båstad municipality, but outside the historical boundaries of the Scanian province.

- The western part of Scania (yellow on the map and close to the Øresund sea) covers 3201.3 km2 of land, and had (in April 2013) 925,982 inhabitants, almost 290 inhabitants/km2

- The other municipalities cover 7281.3 km2of land, and had at the same time only 341,009 inhabitants or 47 inhabitants/km2

- The same figures for the entire province are 10482.6 km2, 1,266,991 inhabitants and 121 inhabitants/km2

These figures can be compared with around to 21 inhabitants per km2 for entire Sweden.

Population around Øresund

Western Scania has a high population density, not only by Scandinavian standards but also by average European standards, at close to 300 inhabitants per square kilometre. But the Danish Copenhagen region at north-east Zealand, on the other side of Øresund Sea, is even more densely populated. The north-east part of Zealand (or the Danish Region Hovedstaden without the Baltic island of Bornholm) has a population density of 878 inhabitants/km2, most of Greater Copenhagen included.

By adding the population of western Scania to the same of Metropolitan area of Copenhagen, then close to 3 million people live around the Øresund sea, within a maximum distance from Øresund of 25 to 30 kilometres, at a land surface of approx. 6100 km2 (approx 460 inhabitants/km2). This is in many ways a better measurement of describing the area around Øresund than what the far wider Øresund Region constitutes, as the latter includes also eastern Scania (whose beaches are Baltic Sea ones and is far less populated) as well as all Denmark east of the Great Belt.

Regardless of counting a smaller area with higher population density or a larger one, the Øresund Strait is located in the largest metropolitan area in Scandinavia with Finland.

Cities

In 1658, the following ten places in Scania were chartered and held town rights: Lund (since approximately 990), Helsingborg (1085), Falsterbo (approximately 1200), Ystad (approximately 1200), Skanör (approximately 1200), Malmö (approximately 1250), Simrishamn (approximately 1300), Landskrona (1413), and Kristianstad (1622). Others had existed earlier, but lost their privileges. Ängelholm got new privileges in 1767, and in 1754, Falsterbo and Skanör were merged. The concept of municipalities was introduced in Sweden in 1863, making each of the towns a city municipality of its own. In the 19th and 20th centuries, four more municipalities were granted city status, Trelleborg (1867), Eslöv (1911), Hässleholm (1914) and Höganäs (1936). The system of city status was abolished in 1971.

Over 90% of Scania's population live in urban areas.[60] In 2000, the Øresund Bridge – the longest combined road and rail bridge in Europe – linked Malmö and Copenhagen, making Scania's population part of a 3.6 million total population in the Øresund Region. In 2005, the region had 9,200 commuters crossing the bridge daily, the vast majority of them from Malmö to Copenhagen.[61]

The following localities had more than 10,000 inhabitants[62] (year 2010).

- Malmö, 280,415*

- Helsingborg, 97,122

- Lund, 82,800

- Kristianstad, 35,711

- Landskrona, 30,499

- Trelleborg, 28,290

- Ängelholm, 23,240

- Hässleholm, 18,500

- Ystad, 18,350

- Eslöv, 17,748

- Staffanstorp, 14,808

- Höganäs, 14,107

- Kävlinge & Furulund, 13,200

Population development

It has been estimated that around 1570, Scania had about 110,000 inhabitants.[64] But before the plague in the middle of the 14th century the population of all Danish territory east of Øresund (Scania, Island of Bornholm, Blekinge and Halland) may have exceeded 250,000.

The figures here are from two different sources.[65][66]

| Year | Population | Year | Population | Year | Population |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1620 | 126,000 | 1820 | 312,000 | 1930 | 757,000 |

| 1699 | 142,000 | 1830 | 350,000 | 1940 | 778,000 |

| 1718 | 152,000 | 1840 | 388,000 | 1950 | 843,000 |

| 1735 | 180,000 | 1850 | 443,000 | 1960 | 882,000 |

| 1750 | 197,000 | 1860 | 494,000 | 1970 | 983,000 |

| 1760 | 202,000 | 1870 | 538,000 | 1980 | 1,023,000 |

| 1772 | 216,000 | 1880 | 580,000 | 1990 | 1,068,000 |

| 1780 | 231,000 | 1890 | 591,000 | 2000 | 1,129,000 |

| 1795 | 250,000 | 1900 | 628,000 | 2010 | 1,228,000 |

| 1800 | 259,000 | 1910 | 685,000 | 2015 | 1,303,600 |

| 1810 | 275,000 | 1920 | 728,000 | 2016 | 1,322,200 |

- 2015 data.[6]

Hundreds

Scania was formerly divided into 23 hundreds.

Climate and seasons

Scania has the mildest climate in Sweden, but there are some local differences.

The table shows average temperatures in degrees Celsius at ten Swedish Meteorological and Hydrological Institute (SMHI) weather stations in Scania and three stations further north for comparison issues. Average temperature in this case means the average of the temperature taken throughout both day and night unlike the more usual daily maximum or minimum average. This is done for specific measured periods of thirty years. The last period began at 1 January 1961 and ended at 31 December 1990. The current such period started at 1 January 1991 and will end by 31 December 2020. At that time it will be possible to with a high degree of mathematical certainty to measure possible climate changes, by comparing two separate periods of 30 years with each other.

| st.no | Station | Approx Latitude | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Annual |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5320 | Smygehuk | 55 | −0.1 | −0.3 | 1.4 | 4.6 | 9.4 | 14.0 | 15.6 | 15.7 | 12.9 | 9.4 | 5.2 | 1.7 | 7.5 |

| 5223 | Falsterbo | 55 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 1.7 | 5.1 | 10.1 | 14.7 | 16.4 | 16.4 | 13.7 | 10.0 | 5.7 | 2.3 | 8.0 |

| 5337 | Malmö 2 | 55.5 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 2.2 | 6.4 | 11.6 | 15.8 | 17.1 | 16.8 | 13.6 | 9.8 | 5.3 | 1.9 | 8.4 |

| 5433 | Simrishamn | 55.5 | −0.1 | −0.3 | 1.7 | 4.9 | 9.5 | 14.6 | 16.3 | 16.1 | 13.1 | 9.2 | 4.9 | 1.6 | 7.6 |

| 5251 | Örja | 55.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.2 | 6.1 | 11.5 | 15.3 | 16.5 | 16.7 | 13.5 | 9.4 | 5.2 | 2.2 | 8.2 |

| 6203 | Helsingborg | 56 | 0.6 | −0.1 | 2.0 | 6.0 | 11.2 | 15.3 | 16.7 | 16.6 | 13.6 | 9.9 | 5.2 | 1.8 | 8.3 |

| 5343 | Lund | 55.5 | −0.6 | −0.5 | 2.0 | 6.0 | 11.5 | 15.4 | 16.8 | 16.5 | 13.1 | 9.1 | 4.5 | 1.1 | 7.9 |

| 5353 | Hörby | 55.5 | −1.6 | −1.5 | 1.0 | 5.4 | 10.4 | 14.4 | 15.5 | 15.3 | 11.9 | 8.0 | 3.6 | 0.1 | 6.9 |

| 5455 | Kristianstad | 55.5 | −1.0 | −1.0 | 1.4 | 5.2 | 10.3 | 14.7 | 16.1 | 15.7 | 12.3 | 8.5 | 4.0 | 0.6 | 7.2 |

| 6322 | Osby | 56 | −2.2 | −2.1 | 0.6 | 5.0 | 10.5 | 14.4 | 15.5 | 14.9 | 11.3 | 7.4 | 2.8 | −0.7 | 6.5 |

| For comparison, some northern locations within Sweden | |||||||||||||||

| 9749 | Stockholm Arlanda | 60 | −4.4 | −4.6 | -1.0 | 4.0 | 10.2 | 14.9 | 16.3 | 15.2 | 10.8 | 6.4 | 1.2 | -2.9 | 5.5 |

| 12731 | Sundsvall | 62.5 | −9.0 | −7.9 | −3.1 | 2.0 | 7.8 | 13.4 | 15.3 | 14.0 | 9.4 | 4.5 | −2.0 | −6.7 | 3.1 |

| 16268 | Luleå | 66 | −11.5 | −10.7 | −6.0 | 0.1 | 6.4 | 13.0 | 15.5 | 13.6 | 8.3 | 3.0 | −4.0 | −9.0 | 1.6 |

[67] All three of the northern locations are at low altitude and fairly close to the Baltic Sea.

Compared with locations further north, the Scanian climate differs primary by being far less cold during the winter and in having longer springs and autumns. While the July temperatures doesn't differ much (see table above).

The highest temperature ever recorded in the province is 36.0 °C (97 °F) (Ängelholm, 30 July 1947) and the lowest ever recorded is −34 °C (−29 °F) (Stehag, 26 January 1942) Temperatures below −15 °C (5 °F) are extremely rare even at night, while summer temperatures above 30 °C (86 °F) occurs once in a while every summer. Precipitation is spread fairly evenly, both across the province and during the year.

Slightly more precipitation falls during July and August than during the other months.

Winter

A typical winter, with average temperatures around the freezing point during January and February, means that a period of mild weather (often windy or/and rainy) is followed by a colder period (when precipitation falls as snow)—and then the mild weather returns etc., rather than a stable temperature close to zero degrees. During the colder periods, the temperature often is below freezing point also during daytime while during the milder periods temperatures below freezing point are unusual even at night. During the mild periods temperatures slightly below freezing point only occur if the night is both calm and free of clouds. If the same circumstances occur during a cold period, the nights can get very cold though. All together this adds up to a 24 hrs/day "winter average" of around 0 degrees In the north-eastern corner (and at the top of the ridges) the winter is in general notably colder though, and a snow cover may last for weeks.

Spring

March is locally known as the first month of the spring. The colder periods are fewer and sunny days may even feel pleasant. During April and early May temperature rises rather fast. Though spring (especially in the sense "first heat") arrives later compared to northernmost Germany and Poland. This is particularly notable in the south-eastern corner. This is explained by the open coastline and low temperatures in the Baltic sea. Øresund is both narrow and shallow, and gets warmer faster. The most common Scanian tree, the beech, usually comes into leaf during the last days of April or the first days of May, but is often delayed by 10–14 days in the south-east, due to the Baltic Sea chill factor.

Summer

Unlike the other seasons, summer is not warmer in Scania compared to many other Swedish provinces. As in winter, the weather usually changes between periods that either are sunny and fairly hot (up to 30 degrees, even higher away from the coastlines), and periods of unstable cloudy and cooler weather. The time between sunset and sunrise during June and earliest July is less than 7 hours, and both the dawn and the dusk are rather long as well. However, there are still a few hours of real night. Further north in Sweden there is no real night, as dusk turns into dawn. (In northernmost Sweden, the sun does not set at all for around two months.)

Autumn

The autumn in Scania is a slow process, compared with more northern parts of Sweden (but a faster one, when comparing with any part of the British Isles). During the first half of September, temperatures usually are not so much affected, but the sunset is obviously earlier compared with in June. Temperatures drop in steps. Every new period with sunny weather becomes a bit cooler than the last one. By the end of October the defoliation process becomes evident. But not until late November have all the trees lost their leaves. The period when storms and even hurricanes becomes most likely to occur is between November and February. Most hurricanes come from the Atlantic Ocean and don't involve snow or temperatures below freezing point. Late Scanian autumn is in general benefited from the surrounding waters (the opposite effect early spring).

Culture

Scania's long-running and sometimes intense trade relations with other communities along the coast of the European continent through history have made the culture of Scania distinct from other geographical regions of Sweden. Its open landscape, often described as a colourful patchwork quilt of wheat and rapeseed fields, and the relatively mild climate at the southern tip of the Scandinavian Peninsula, have inspired many Swedish artists and authors to compare it to European regions like Provence in southern France and Zeeland in the Netherlands.[68] Among the many authors who have described the "foreign" continental elements of the Scanian landscape, diet and customs are August Strindberg and Carl Linnaeus. In 1893 August Strindberg wrote about Scania: "In beautiful, large wave lines, the fields undulate down toward the lake; a small deciduous forest limits the coastline, which is given the inviting look of the Riviera, where people shall walk in the sun, protected from the north wind. [...] The Swede leaves the plains with a certain sense of comfort, because its beauty is foreign to him." In another chapter he states: "The Swedes have a history that is not the history of the South Scandinavians. It must be just as foreign as Vasa’s history is to the Scanian."[69]

In Ystad, singer-songwriter Michael Saxell's popular Scanian anthem Om himlen och Österlen (Of Heaven and Österlen), the flat, rolling hill landscape is described as appearing to be a little closer to heaven and the big, unending sky.

Scania's historical connection to Denmark, the vast fertile plains, the deciduous forests and the relatively mild climate make the province culturally and physically distinct from the emblematic Swedish cultural landscape of forests and small hamlets.[70]

Architecture

Traditional Scanian architecture is shaped by the limited availability of wood; it incorporates different applications of the building technique called half-timbering. In the cities, the infill of the façades consisted of bricks,[71] whereas the country-side half-timbered houses had infill made of clay and straw.[72] Unlike many other Scanian towns, the town of Ystad has managed to preserve a rather large core of its half-timbered architecture in the city center—over 300 half-timbered houses still exist today.[73] Many of the houses in Ystad were built in the renaissance style that was common in the entire Øresund Region, and which has also been preserved in Elsinore (Helsingør). Among Ystad's half-timbered houses is the oldest such building in Scandinavia, Pilgrändshuset from 1480.[74]

In Göinge, located in the northern part of Scania, the architecture was not shaped by a scarcity of wood, and the pre-17th-century farms consisted of graying, recumbent timber buildings around a small grass and cobblestone courtyard. Only a small number of the original Göinge farms remain today. During two campaigns, the first in 1612 by Gustav II Adolf and the second by Charles XI in the 1680s, entire districts were levelled by fire.[75] In Örkened Parish, in what is now eastern Osby Municipality, the buildings were destroyed to punish the different villages for their protection of members of the Snapphane movement in the late 17th century.[76] An original, 17th century Göinge farm, Sporrakulla Farm, has been preserved in a forest called Kullaskogen, a nature reserve close to Glimåkra in Östra Göinge. According to the local legend, the farmer saved the farm in the first raid of 1612 by setting a forest fire in front of it, making the Swedish troops believe that the farm had already been plundered and set ablaze.[77]

A number of Scanian towns flourished during the Viking Age. The city of Lund is believed to have been founded by the Viking-king Sweyn Forkbeard.[78] Scanian craftsmen and traders were prospering during this era and Denmark's first and largest mint was established in Lund. The first Scanian coins have been dated to 870 AD.[79] The archaeological excavations performed in the city indicate that the oldest known stave church in Scania was built by Sweyn Forkbeard in Lund in 990.[80] In 1103, Lund was made the archbishopric for all of Scandinavia.[81]

Many of the old churches in today's Scanian landscape stem from the medieval age, although many church renovations, extensions and destruction of older buildings took place in the 16th and 19th century. From those that have kept features of the authentic style, it is still possible to see how the medieval, Romanesque or Renaissance churches of Danish Scania looked like. Many Scanian churches have distinctive crow-stepped gables and sturdy church porches, usually made of stone.

The first version of Lund Cathedral was built in 1050, in sandstone from Höör, on the initiative of Canute the Holy.[81] The oldest parts of today's cathedral are from 1085, but the actual cathedral was constructed during the first part of the 12th century with the help of stone cutters and sculptors from the Rhine valley and Italy, and was ready for use in 1123. It was consecrated in 1145 and for the next 400 years, Lund became the ecclesiastical power center for Scandinavia and one of the most important cities in Denmark.[80] The cathedral was altered in the 16th century by architect Adam van Düren and later by Carl Georg Brunius and Helgo Zetterwall.

Scania also has churches built in the gothic style, such as Saint Petri Church in Malmö, dating from the early 14th century. Similar buildings can be found in all Hansa cities around the Baltic Sea (such as Helsingborg and Rostock). The parishes in the countryside did not have the means for such extravagant buildings. Possibly the most notable countryside church is the ancient and untouched stone church in Dalby. It is the oldest stone church in Sweden, built around the same time as Lund cathedral. After the Lund Cathedral was built, many of the involved workers travelled around the province and used their acquired skills to make baptism fonts, paintings and decorations, and naturally architectural constructions.

Scania has 240 palaces and country estates—more than any other province in Sweden.[82] Many of them received their current shape during the 16th century, when new or remodelled castles started to appear in greater numbers, often erected by the reuse of stones and material from the original 11th–15th-century castles and abbeys found at the estates. Between 1840 and 1900, the landed nobility in Scania built and rebuilt many of the castles again, often by modernizing previous buildings at the same location in a style that became typical for Scania. The style is a mixture of different architectural influences of the era, but frequently refers back to the style of the 16th-century castles of the Reformation era, a time when the large estates of the Catholic Church were made Crown property and the abbeys bartered or sold to members of the aristocracy by the Danish king.[83] For many of the 19th century remodels, Danish architects were called in. According to some scholars, the driving force behind the use of historical Scanian architecture, as interpreted by 19th century Danish architects using Dutch Renaissance style, was a wish to refer back to an earlier era when the aristocracy had special privileges and political power in relation to the Danish king.[84]

Language, literature, and art

Scanian dialects have various local native idioms and speech patterns, and realizes diphthongs and South Scandinavian Uvular trill, as opposed to the supradental /r/-sound characteristic of spoken Standard Swedish. They are very similar to the dialect of Danish spoken in Bornholm, Denmark. The prosody of the Scanian dialects has more in common with German, Danish and Dutch (and sometimes also with English, although to a lesser extent) than with the prosody of central Swedish dialects.[85]

Famous Scanian authors include Victoria Benedictsson, (1850–1888) from Domme, Trelleborg, who wrote about the inequality of women in the 19th century society, but who also authored regional stories about Scania, such as Från Skåne of 1884; Ola Hansson[86] (1860–1925) from Hönsinge, Trelleborg; Vilhelm Ekelund (1880–1949) from Stehag, Eslöv; Fritiof Nilsson Piraten (1895–1972) from Vollsjö, Sjöbo; Hjalmar Gullberg (1898–1961) from Malmö; Artur Lundkvist (1906–1991) from Hagstad, Perstorp; Hans Alfredsson (born 1931) and Jacques Werup (born 1945), both from Malmö. Birgitta Trotzig (1929-2011) from Gothenburg has written several historic novels set in Scania, such as The Exposed of 1957, which describes life in 17th century Scania with a primitive country priest as its main character and the 1961 novel A Tale from the Coast, which recounts a legend about human suffering and is set in Scania in the 15th century. Gabriel Jönsson (1892–1984) from Ålabodarna, Landskrona.

A printing-house was established in the city of Malmö in 1528. It became instrumental in the propagation of new ideas and during the 16th century, Malmö became the center for the Danish reformation.[87]

Scanian culture, as expressed through the medium of textile art, has received international attention during the last decade.[88] The art form, often referred to as Scanian Marriage Weavings, flourished from 1750 for a period of 100 years, after which it slowly vanished. Consisting of small textile panels mainly created for wedding ceremonies, the art is strongly symbolic, often expressing ideas about fertility, longevity and a sense of hope and joy.[89] The Scanian artists were female weavers working at home, who had learned to weave at a young age, often in order to have a marriage chest filled with beautiful tapestries as a dowry.[90]

According to international collectors and art scholars, the Scanian patterns are of special interest for the striking similarities with Roman, Byzantine and Asian art. The designs are studied by art historians tracing how portable decorative goods served as transmitters of art concepts from culture to culture, influencing designs and patterns along the entire length of the ancient trade routes.[90] The Scanian textiles show how goods traded along the Silk Road brought Coptic, Anatolian, and Chinese designs and symbols into the folk art of far away regions like Scania, where they were reinterpreted and integrated into the local culture. Some of the most ancient designs in Scanian textile art are pairs of birds facing a tree with a "great bird" above, often symbolized simply by its wings.[90] Regionally derived iconography include mythological Scanian river horses in red (Swedish: bäckahästar), with horns on their foreheads and misty clouds from their nostrils.[90] The horse motif has been traced to patterns on 4th- and 5th-century Egyptian fabrics, but in Scanian art it is transformed to illustrate the Norse river horse of Scanian folklore.[91]

Dukes

The title of duke was reintroduced in Sweden in 1772 and since this time, Swedish princes have been created dukes of various provinces, although the titles are purely nominal.

The Dukes of Scania have been:

- Crown Prince Carl (from his birth in 1826 until he became king in 1859)

- Crown Prince Gustaf Adolf (from his birth in 1882 until he became king in 1950)

- Prince Oscar 2016-

From his marriage, in 1905, King Gustaf VI Adolf had his summer residence at Sofiero Palace in Helsingborg. He and his family spent their summers there, and the cabinet meetings held there during the summer months forced the ministers to arrive by night train from Stockholm. He died at Helsingborg Hospital in 1973.

Sports

Football has always been the most popular arena and team sport within the province, from attendances not least. Clubs are administered by Skånes Fotbollförbund.

Malmö FF has won Allsvenskan 23 times, Helsingborg IF 7 times and was one of the twelve clubs in the league's very first season, 1924/25. Also Landskrona BoIS was among the twelve original clubs, but has never won. These three clubs are historically the most famous football clubs in Scania. But also IFK Malmö, Stattena IF, Råå IF (the latter two clubs are both from Helsingborg) as well as Trelleborgs FF have participated.

Handball is also a relatively popular team sport, whilst Basketball never really has gained much interest.

Ice hockey was for a long time thought of as a sport of northern Sweden, but has nevertheless became a popular attendance sport too. Malmö Redhawks has even become Swedish Champions twice, but also Rögle BK (from Ängelholm) have participated at the highest level of Swedish ice hockey during quite a lot of seasons.

Rugby is played in Scania by the Skåne Crusaders who play in the Sweden Rugby League.

The overwhelmingly largest sport related events in both Scanian as well as Swedish history, were however the motorcycle Saxtorp TT-races during the 1930s, which most of the years gathered crowds of 150.000 or more.

Tennis is associated with Båstad during the Swedish Open.

Golf is the most popular sport to exercise after a certain age, at least. Scania has a large amount of golf courses, of which Barsebäck Golf & Country Club is the most well-known. Most Golf courses are open also during the winter, but may sometimes close temporarily in cases of snowy periods.

See also

- 2008 Skåne County earthquake

- 460 Scania, an asteroid discovered in 1900

- Sång till Skåne, a song about the province

Notes

- "Statistics Sweden". Archived from the original on 20 August 2010.

- "Folkmängd i landskapen den 31 december 2016". Statistiska Centralbyrån. Archived from the original on 19 October 2017. Retrieved 9 October 2017.

- The Danish name is spelled the same and pronounced [ˈskɔːnə].

- "Prices | Øresundsbron". Uk.oresundsbron.com. Archived from the original on 13 March 2013. Retrieved 3 March 2010.

- "Öresundsregionen.se". Oresundsregionen.se. Archived from the original on 30 December 2009. Retrieved 3 March 2010.

- "Folkmängd 31 december; ålder - Regionfakta". www.regionfakta.com. Archived from the original on 27 October 2016. Retrieved 27 October 2016.

- Graham, Brian and Peter Howard, eds. (2008). The Ashgate Research Companion to Heritage and Identity Archived 28 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7546-4922-9, p. 79

- Riksarkivet. "Riksarkivet - Sök i arkiven". riksarkivet.se. Archived from the original on 15 February 2019. Retrieved 16 February 2019.

- "See 3.July 1720 at Swedish National Archive". Archived from the original on 15 February 2019. Retrieved 16 February 2019.

- Skane | county and province, Sweden | Britannica.com. Global.britannica.com. Retrieved on 24 June 2015.

- "Sweden / Skåne". Geographia.com. Archived from the original on 24 March 2010. Retrieved 3 March 2010.

- "Skane, Sweden". Planetware.com. Archived from the original on 10 February 2009. Retrieved 3 March 2010.

- "Map of Skane in Sweden". Map-of-sweden.co.uk. Archived from the original on 7 August 2010. Retrieved 3 March 2010.

- Archived 26 February 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- North, Richard (1997). Heathen Gods in Old English Literature Archived 23 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Cambridge University Press: 1997, ISBN 978-0-521-55183-0, p. 192.

- Svenskt ortnamnslexikon, 2003

- Björkman, Erik (1973). Studien über die Eigennamen im Beowulf Archived 23 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine. M. Sändig, ISBN 978-3-500-28470-5, p. 99.

- Haugen, Einar (1976). The Scandinavian Languages: An Introduction to Their History. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1976.

- Helle, Knut (2003). "Introduction". The Cambridge History of Scandinavia. Ed. E. I. Kouri et al. Cambridge University Press, 2003. ISBN 978-0-521-47299-9. p. XXII. "The name Scandinavia was used by classical authors in the first centuries of the Christian era to identify Scania and the mainland further north which they believed to be an island."

- Olwig, Kenneth R. "Introduction: The Nature of Cultural Heritage, and the Culture of Natural Heritage—Northern Perspectives on a Contested Patrimony". International Journal of Heritage Studies, Vol. 11, No. 1, March 2005, p. 3: "The very name 'Scandinavia' is of cultural origin, since it derives from the Scanians or Scandians (the Latinised spelling of Skåninger), a people who long ago lent their name to all of Scandinavia, perhaps because they lived centrally, at the southern tip of the peninsula."

- Østergård, Uffe (1997). "The Geopolitics of Nordic Identity – From Composite States to Nation States". The Cultural Construction of Norden. Øystein Sørensen and Bo Stråth (eds.), Oslo: Scandinavian University Press 1997, 25-71.

- Anderson, Carl Edlund (1999). Formation and Resolution of Ideological Contrast in the Early History of Scandinavia. PhD dissertation, Department of Anglo-Saxon, Norse & Celtic (Faculty of English), University of Cambridge, 1999.

- Helle, Knut (2003). "Introduction". The Cambridge History of Scandinavia. Ed. E. I. Kouri et al. Cambridge University Press, 2003. ISBN 978-0-521-47299-9.

- Region Skåne. Municipalities in Skåne. Official site. Retrieved 24 August 2007.

- Clara Nevéus, Bror Jacques de Wærn: Ny svensk vapenbok. Riksarkivet 1992. (In Swedish)

- Vårt vapen. Region Skåne. (In Swedish). Retrieved 4 April 2008.

- 3 juli 1720 - Riksarkivet - Sök i arkiven Archived 28 January 2015 at the Wayback Machine. Sok.riksarkivet.se. Retrieved on 24 June 2015.

- Fredstraktat, tillige med dend: over bemelte Freds-tractat forfattede ... - Google Břger Archived 23 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Books.google.dk. Retrieved on 24 June 2015.

- "Trots motstånd – skånska flaggan blir officiell". sydsvenskan.se. Archived from the original on 29 November 2017. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- "Trots motstånd – nu blir skånska flaggan officiell". aftonbladet.se. Archived from the original on 10 December 2017. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- McCallion, Malin Stegmann (2004). The Europeanisation of Swedish Regional Government Archived 3 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Policy Networks in Sub National Governance: Understanding Power Relations. Paper 8, Workshop 25, European Consortium of Political Research. 2004 Joint Sessions of Workshops, Uppsala, Sweden.

- Peterson, Martin (2003). "The Regions and Regionalism: Regionalism in Sweden" Archived 13 November 2007 at the Wayback Machine. CoR Report Sweden. The Interdisciplinary Centre for Comparative Research in the Social Sciences, EUROPUB Case Study (WP2).

- Kramsch, Olivier and Olivier Thomas (2004). Cross-border Governance in the European Union Archived 23 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Routledge, 2004, ISBN 978-0-415-31541-8.

- Peterson, Martin (2003). "The Regions and Regionalism and Regionalism: Regionalism in Sweden" Archived 13 November 2007 at the Wayback Machine. CoR Report Sweden, The Interdisciplinary Centre for Comparative Research in the Social Sciences, EUROPUB Case Study (WP2). Final Report.

- as stated in the train map info, "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 21 August 2014. Retrieved 11 September 2014.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link), and press for PDF "Linjekarta fær tåg (pdf)" Note though that this PDF also shows a part of the Copenhagen rail network

- Sveriges järnvägsnät - Trafikverket Archived 14 September 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Trafikverket.se (31 March 2015). Retrieved on 24 June 2015.

- Last part of http://www.trafikverket.se/Privat/Vagar-och-jarnvagar/Sveriges-jarnvagsnat/Vastkustbanan/ "Enligt vår nuvarande planering kommer utbyggnaden till största delen vara klar 2012–2014. Några sträckor kommer då att återstå, bland annat sträckan genom Varberg och sträckan Ängelholm–Helsingborg. Tunneln genom Hallandsås planeras vara klar 2015." No dual tracks exist between Helsingborg and Ängelholm

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 21 August 2014. Retrieved 11 September 2014.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link); chose "linjekarta för tåg (PDF)"

- "The final span over the Öresund". Archived from the original on 11 July 2011.

- Helsingborg ferry, compare prices, times and book tickets Archived 6 July 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Directferries.co.uk. Retrieved on 24 June 2015.

- "2013 satte Københavns Lufthavn for tredje år i træk passagerrekord, da 24,1 million passagerer rejste gennem lufthavnen". Archived from the original on 27 August 2014. Retrieved 11 September 2014.

- Österberg, Klas (2001). Forest - Geographical Regions. The Swedish Environmental Protection Agency, 25 January 2001. Retrieved 4 November 2006. Archived 30 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- SCB. Jordbruksstatistisk årsbok 2006. (Agricultural Statistic Yearbook 2006). Published online in pdf-format Archived 3 January 2007 at the Wayback Machine by Statiska Centralbyrån (Statistics Sweden). (In Swedish). Retrieved 10 January 2007.

- Hogan, C.M. (2004). Kullaberg environmental analysis. Lumina Technologies prepared for municipality of Höganäs, Aberdeen Library Archives, Aberdeen, Scotland, 17 July 2004.

- Lidmar-Bergström, Karna; Elvhage, Christian; Ringberg, Bertil (1991). "Landforms in Skåne, South Sweden". Geografiska Annaler. Series A, Physical Geography. 73 (2): 61–91. doi:10.2307/520984. JSTOR 520984.

- Lundin, Jonas (13 November 2013). "Söderåsen ingen riktig ås". Lokaltidningen Landskrona Svalöv (in Swedish). Archived from the original on 27 October 2017. Retrieved 25 October 2017.

- Lidmar-Bergström, Karna and Jens-Ove Näslund (2005). "Uplands and Lowlands in Southern Sweden". In The Physical Geography of Fennoscandia. Ed. Matti Seppälä. Oxford University Press, 2005, pp. 255–261. ISBN 978-0-19-924590-1.

- Bergelin, Ingemar (2009). "Jurassic volcanism in Skåne, southern Sweden, and its relation to coeval regional and global events". GFF. 131 (1–2): 165–175. doi:10.1080/11035890902851278.

- Augustsson, Carita (2001). "Lapilli tuff as evidence of Early Jurassic Strombolian-type volcanism in Scania, southern Sweden". GFF. 123 (1): 23–28. doi:10.1080/11035890101231023.

- Lidmar-Bergström, Karna; Olvmo, Mats; Bonow, Johan M. (2017). "The South Swedish Dome: a key structure for identification of peneplains and conclusions on Phanerozoic tectonics of an ancient shield". GFF.

- Lidmar-Bergström, Karna; Bonow, Johan M.; Japsen, Peter (2013). "Stratigraphic Landscape Analysis and geomorphological paradigms: Scandinavia as an example of Phanerozoic uplift and subsidence". Global and Planetary Change. 100: 153–171. doi:10.1016/j.gloplacha.2012.10.015.

- Surlyk, Finn; Sørensen, Anne Mehlin (2010). "An early Campanian rocky shore at Ivö Klack, southern Sweden". Cretaceous Research. 31 (6): 567–576. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2010.07.006.

- "Nationalparker och andra fina platser - Naturvårdsverket - Swedish EPA". Naturvardsverket.se. 6 November 2009. Archived from the original on 7 February 2010. Retrieved 4 March 2010.

- "Dalby Söderskog, Skåne län - Naturvårdsverket - Swedish EPA". Naturvardsverket.se. 3 August 2009. Archived from the original on 15 October 2008. Retrieved 6 March 2010.

- "Welcome - Länsstyrelsen i Skåne". Lst.se. 18 June 2009. Archived from the original on 20 August 2010. Retrieved 6 March 2010.

- "Söderåsen National Park". Nationalpark-soderasen.lst.se. Archived from the original on 5 July 2010. Retrieved 6 March 2010.

- "skanebravaden.se". skanebravaden.se. Archived from the original on 18 August 2010. Retrieved 4 March 2010.

- inahbitants "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 4 January 2014.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Churches - Eslövs kommun". Eslov.se. 30 September 2009. Archived from the original on 14 July 2010. Retrieved 5 March 2010.

- The Foundation for Recreational Areas in Skåne. "Information about the Skaneled Trails" Archived 18 October 2003 at the Wayback Machine. Region Skåne. Retrieved 20 October 2006.

- Peter, Laurence. "Bridge shapes new Nordic hub" Archived 27 February 2007 at the Wayback Machine. BBC News, 14 September 2006. Retrieved 20 October 2006.

- "Tätortsstatistik från Statistiska centralbyrån".

- "Tallest Building In Sweden Opens, And Is Pretty Twisted Looking". The Huffington Post. 28 August 2005. Archived from the original on 21 October 2010. Retrieved 30 July 2010.

- "De svenska länens befolkning". Tacitus.nu. 7 September 2008. Archived from the original on 29 June 2009. Retrieved 5 March 2010.

- Folkmängden i Sveriges socknar och kommuner 1571–1991

- B. R. Mitchell: International Historical Statistics 1750–1993

- Source: Swedish Meteorological and Hydrological Institute, SMHI. From http://www.smhi.se/polopoly_fs/1.2860!ttm6190%5B1%5D.pdf Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine, the number and name of all Swedish meteorological weather stations are available. By the use of the station number, the average temperature for each months and annual average is available at http://data.smhi.se/met/climate/time_series/month_year/normal_1961_1990/SMHI_month_year_normal_61_90_temperature_celsius.txt Archived 9 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine The exact location of the stations is given in the internal Swedish "Coordinates of the reich", however four figured stations numbers that begins with a "5" is located between the 55th and 56th latitude, "6" between 56th and 57th latitude etc.

- Linnaeus, Carl (1750). Skånska resa (Scanian Journey).

- Strindberg, August (1893). "Skånska landskap med utvikningar". Prosabitar från 1890-talet. Bonniers, Stockholm, 1917. (In Swedish).

- Germundsson, Tomas (2005). "Regional Cultural Heritage versus National Heritage in Scania’s Disputed National Landscape." International Journal of Heritage Studies, Vol. 11, No. 1, March 2005, pp. 21–37. (ISSN 1470-3610).

- Albertsson, Rolf. "Half-timbered houses". Section in Malmö 1692 - a historical project. Malmö City Culture Department and Museum of Foteviken. Retrieved 16 January 2007. Archived 29 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- Oresundstid.Images: Half-timbered house in Scania. Retrieved 16 January 2007. Archived 13 August 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- Ystad Municipality. Welcome to Ystad Archived 3 January 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Official site. Retrieved 16 January 2007.

- Ystad Municipality. A walk through the centuries, section "Pedestrian street". Official site. Retrieved 16 January 2007. Archived 11 June 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- A letter from the Swedish king Gustav II Adolf describes a raid in 1612: "We have been in Scania and we have burned most of the province, so that 24 parishes and the town of Vä lie in ashes. We have met no resistance, neither from cavalry nor footmen, so we have been able to rage, plunder, burn and kill to our hearts' content. We had thought of visiting Århus in the same way, but when it was brought to our knowledge that there were Danish cavalry in the town, we set out for Markaryd and we could destroy and ravage as we went along and everything turned out lucky for us." (Quoted and translated by Oresundstid in the section "Skåne was ravaged" Archived 19 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine.)

- Herman Lindquist (1995). Historien om Sverige – storhet och fall. Norstedts Förlag, 2006. ISBN 978-91-1-301535-4. (In Swedish).

- Skåneleden: 6B. Breanäsleden Archived 23 February 2007 at the Wayback Machine (In Swedish). Official site by The Foundation for Recreational Areas in Skåne and Region Skåne. See also Göingebygden, official site by Skåne Nordost Tourism Office and The Snapp-hane Kingdom. Official site by Osby Tourism Office.

- "Touchdowns in the History of Lund - Lunds kommun". Lund.se. 17 February 2010. Archived from the original on 9 May 2010. Retrieved 30 July 2010.

- Hauberg, P. (1900). Myntforhold og Udmyntninger i Danmark indtil 1146. D. Kgl. Danske Vidensk. Selsk. Skr., 6. Række, historisk og filosofisk Afd. V. I., Chapter III: Danmarks Mynthistorie indtil 1146 Archived 20 February 2007 at the Wayback Machine, and Chapter V: Myntsteder Archived 20 February 2007 at the Wayback Machine published online by Gladsaxe Gymnasium. (In Danish). Retrieved 10 January 2007.

- City of Lund. Touchdowns in the History of Lund Archived 24 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Official site for the City of Lund. Retrieved 10 January 2006.

- Terra Scaniae. Lunds Domkyrka Archived 31 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine. (In Swedish). Retrieved 11 January 2007.

- Region Skåne (2006). What is typical Skåne?. Official site. Retrieved 22 January 2007.

- Terra Scaniae. 1600-talet. (In Swedish). Retrieved 27 January 2007. Archived 30 December 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- Bjurklint Rosenblad, Kajsa. Scenografi för ett ståndsmässigt liv: adelns slottsbyggande i Skåne 1840-1900. Malmö: Sekel, 2005. ISBN 978-91-975222-3-6. Abstract in English at Scripta Academica Lundensia, Lund University. Archived 23 July 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- Gårding, Eva (1974). "Talar skåningarna svenska?" (Do Scanians speak Swedish?). Svenskans beskrivning. Ed. Christer Platzack. Lund: Institutionen för nordiska språk, 1973, p 107, 112. (In Swedish)

- "Poems" of 1884 and "Notturno" of 1885 celebrate the natural beauty and folkways of Scania. The result of a globetrotting life style, Ola Hansson's later poetry had various continental influences, but like many other Scanian writers', his authorship often reflected the tension between cosmopolitan culture and regionalism. For larger trends and a historic perspective on Scanian literature, see Vinge, Louise (ed.) Skånes litteraturhistoria del I, ISBN 978-91-564-1048-2, and Skånes litteraturhistoria del II, ISBN 978-91-564-1049-9, Corona: Malmö, 1996–1997. (In Swedish).

- Infotek Öresund. Litteraturhistoria, Malmö Archived 5 January 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Fact sheet produced by Infotek Öresund, a cooperative project between the public libraries of Helsingborg, Elsinore, Copenhagen and Malmö, published online by Malmö Public Library, 4 November 2005. (In Swedish).

- See for example: Monument to Love and Textiles de Skåne des XVIIIe et XIXe Siècles. Scanian textiles from the Khalili Collection exhibited at the Swedish Cultural Centre in Paris and the Boston University Art Gallery. Retrieved 15 January 2007. "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 18 January 2007. Retrieved 16 January 2007.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- Keelan, Major Andrew and Wendy Keelan. The Khalili Collection - An Introduction. The Khalili Family Trust. Retrieved 15 January 2007. Archived 18 January 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- Hansen, Viveka (1997). Swedish Textile Art: Traditional Marriage Weavings from Skåne. Nour Foundation: 1997. ISBN 978-1-874780-07-6.

- Lundström, Lena (2003). "Vattenväsen i väverskans händer". Curator's description of the exhibition "Aqvaväsen" at Trelleborgs Museum in Vårt Trelleborg, 2:2003, pp. 20-21. Available online in pdf format Archived 26 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine. (In Swedish).

References

- Albertsson, Rolf (2007). "Half-timbered houses". Malmö 1692 - a historical project. Malmö City Culture Department and Museum of Foteviken. Retrieved 16 January 2007.

- Anderson, Carl Edlund (1999). Formation and Resolution of Ideological Contrast in the Early History of Scandinavia. PhD dissertation, Department of Anglo-Saxon, Norse & Celtic (Faculty of English), University of Cambridge, 1999.

- Björk, Gert and Henrik Persson. "Fram för ett öppet och utåtriktat Skåne". Sydsvenskan, 20 May 2000. Reproduced by FSF. (In Swedish). Retrieved 3 April 2008.

- Bjurklint Rosenblad, Kajsa (2005). Scenografi för ett ståndsmässigt liv: adelns slottsbyggande i Skåne 1840-1900. Malmö: Sekel, 2005. ISBN 978-91-975222-3-6.

- Bonney, Richard (1995). Economic Systems and State Finance. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-820545-6.

- Craig, David J. (2003). "Monument to Love". Boston University Bridge, 29 August 2003,• Vol. VII, No. 1. Retrieved 2 April 2008.

- Danish National Archives (2006). Lensregnskaberne 1560-1658. (In Danish). Retrieved 20 October 2006.

- City of Lund (2006).Touchdowns in the History of Lund. Retrieved 10 January 2006.

- Gårding, Eva (1974). "Talar skåningarna svenska". Svenskans beskrivning. Ed. Christer Platzack. Lund: Institutionen för nordiska språk, 1973. (In Swedish)

- Germundsson, Tomas (2005). "Regional Cultural Heritage versus National Heritage in Scania’s Disputed National Landscape." International Journal of Heritage Studies, Vol. 11, No. 1, March 2005. ISSN 1470-3610.

- Hansen, Viveka (1997). Swedish Textile Art: Traditional Marriage Weavings from Scania. Nour Foundation: 1997. ISBN 978-1-874780-07-6.

- Hauberg, P. (1900). Myntforhold og Udmyntninger i Danmark indtil 1146. D. Kgl. Danske Vidensk. Selsk. Skr., 6. Række, historisk og filosofisk Afd. V. I., Chapter III: Danmarks Mynthistorie indtil 1146, and Chapter V: Myntsteder, Gladsaxe Gymnasium. (In Danish). Retrieved 10 January 2007.

- Haugen, Einar (1976). The Scandinavian Languages: An Introduction to Their History. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1976.

- Helle, Knut, ed. (2003). The Cambridge History of Scandinavia. Cambridge University Press, 2003. ISBN 978-0-521-47299-9.

- Hogan, C.M. (2004). Kullaberg environmental analysis. Lumina Technologies, Aberdeen Library Archives, Aberdeen, Scotland, 17 July 2004.

- Jespersen, Knud J. V. (2004) . A History of Denmark. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-333-65917-5.

- Keelan, Major Andrew and Wendy Keelan (2006). The Khalili Collection. The Khalili Family Trust. Retrieved 1 April 2008.

- Lidmar-Bergström, Karna and Jens-Ove Näslund (2005). "Uplands and Lowlands in Southern Sweden". The Physical Geography of Fennoscandia. Ed. Matti Seppälä. Oxford University Press, 2005. ISBN 978-0-19-924590-1.

- Lindquist, Herman (1995). Historien om Sverige – storhet och fall. Norstedts Förlag, 2006. ISBN 978-91-1-301535-4. (In Swedish).

- Linnaeus, Carl (1750). Skånska resa. (In Swedish).

- Lund University School of Aviation (2005). Ljungbyhed airport - ESTL. Retrieved 22 January 2007.

- Lundström, Lena (2003). "Vattenväsen i väverskans händer". Vårt Trelleborg, 2:2003. (In Swedish).

- Malmö Public Library (2005). Litteraturhistoria, Malmö. Infotek Öresund, 4 November 2005. (In Swedish).

- Nevéus, Clara and Bror Jacques de Wærn (1992). Ny svensk vapenbok. Riksarkivet 1992. (In Swedish)

- Olin, Martin (2005). "Royal Galleries in Denmark and Sweden around 1700". Kungliga rum – maktmanifestation och distribution. Historikermöte 2005, Uppsala University. Retrieved 2 April 2008.

- Olwig, Kenneth R. (2005). "Introduction: The Nature of Cultural Heritage, and the Culture of Natural Heritage—Northern Perspectives on a Contested Patrimony". International Journal of Heritage Studies, Vol. 11, No. 1, March 2005.

- Oresundstid (2008). "The Swedification of Scania", "Renaissance Houses: Half-timbered houses". Retrieved 2 April 2008.

- Österberg, Klas (2001). Forest - Geographical Regions. The Swedish Environmental Protection Agency, 25 January 2001. Retrieved 4 November 2006.

- Østergård, Uffe (1997). "The Geopolitics of Nordic Identity – From Composite States to Nation States". The Cultural Construction of Norden. Øystein Sørensen and Bo Stråth (eds.), Oslo: Scandinavian University Press 1997.

- Peter, Laurence (2006). "Bridge shapes new Nordic hub". BBC News, 14 September 2006. Retrieved 20 October 2006.

- Region Skåne (2007). Municipalities in Skåne, Democracy-Increased autonomy.What is typical Skåne?. Retrieved 22 January 2007.

- Sawyer, Birgit; Sawyer, Peter H. (1993). Medieval Scandinavia: from Conversion to Reformation, Circa 800–1500. University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 978-0-8166-1739-5.

- SCB (2007). "Skördar". Jordbruksstatistisk årsbok 2006. Statiska Centralbyrån. (In Swedish). Retrieved 10 January 2007.

- Skåne Regional Council (1999). Newsletter., No. 2, 1999.

- Stadin, Kekke (2005). "The Masculine Image of a Great Power: Representations of Swedish imperial power c. 1630–1690". Scandinavian Journal of History, Vol. 30, No. 1. March 2005, pp. 61–82. ISSN 0346-8755.

- Stiftelsen för fritidsområden i Skåne (2006).Skåneleden: 6B. Breanäsleden (In Swedish), Information about the Skaneled Trails. The Foundation for Recreational Areas in Skåne and Region Skåne. Retrieved 11 April 2008.

- Strindberg, August (1893). "Skånska landskap med utvikningar". Prosabitar från 1890-talet. Bonniers, Stockholm, 1917. (In Swedish).

- SAOB (2008). Skåneland.(In Swedish). Retrieved 2 April 2008.

- Sorens, Jason (2005). "The Cross-Sectional Determinants of Secessionism in Advanced Democracies". Comparative Political Studies, Vol. 38, No. 3, 304-326 (2005). doi:10.1177/0010414004272538 2005 SAGE Publications.

- Språk- och Folkminnesinstitutet (2003). Svenskt Ortnamnslexikon. Uppsala, 2003. (In Swedish)

- Tägil, Sven (2000). "Regions in Europe – a historical perspective". In Border Regions in Comparison. Ed. Hans-Åke Persson. Studentlitteratur, Lund. ISBN 978-91-44-01858-4.

- Terra Scaniae (2008). Skånes län efter 1658, Hårdare försvenskning, "Kuppförsök mot svenskarna 1658", "Lunds Domkyrka", 1600-talet, Generalguvernörens uppgifter.(In Swedish). Retrieved 2 April 2008.

- Upton, Anthony F. (1998). Charles XI and Swedish Absolutism, 1660–1697. Cambridge University Press, 1998. ISBN 978-0-521-57390-0.

- Vinge, Louise (ed.) Skånes litteraturhistoria, Corona: Malmö, 1996–1997, Part I, ISBN 978-91-564-1048-2, and Part II, ISBN 978-91-564-1049-9. (In Swedish).

- Ystad Municipality (2007). Welcome to Ystad and "Pedestrian street". A walk through the centuries. Retrieved 16 January 2007.

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Scania. |

Official links

- Region Skåne - The County council

- Scania's Public Recreational Areas - Region Skåne's public forests and parks

- Skåne - Business Region Skåne's official website for culture, heritage and tourism

- Länsstyrelsen - County Administration Board

- Skåneleden - Public nature trails through Scania

Organizations

- Oresund Region - The regional body of the Oresund Region

- Regional Museum - Museum in Kristianstad

- Kommunförbundet Skåne - A cooperation between Scania's 33 municipalities

- Skånes hembygdsförbund (in Swedish) - Heritage conservation organization

- Terra Scaniae - History project established for Scanian schools, financed with subsidies from Skåne Regional Council.