Ale

Ale is a type of beer brewed using a warm fermentation method, resulting in a sweet, full-bodied and fruity taste.[1][2] Historically, the term referred to a drink brewed without hops.[3]

As with most beers, ale typically has a bittering agent to balance the malt and act as a preservative. Ale was originally bittered with gruit, a mixture of herbs or spices boiled in the wort before fermentation. Later, hops replaced gruit as the bittering agent.[4]

Etymology

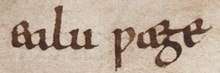

The word ale is related to the Old English alu or ealu. It is believed to stem from Proto-Indo-European root *alu-, through Proto-Germanic *aluth-.[5] This is a cognate of Old Saxon alo, Danish, Norwegian, Swedish, Faroese, Icelandic and Old Norse öl/øl, Finnish olut, Estonian õlu, Old Bulgarian olu cider, Slovenian ol, Old Prussian alu, Lithuanian alus, Latvian alus.[6]

History of ale

Ale was an important source of nutrition in the medieval world. It was one of three main sources of grains at the start of the fourteenth century in England , along with pottage and breads.[7] Scholars believe grains accounted for around 80% of the calorie intake of agricultural workers and 75% for soldiers. Even nobles received around 65% of their calories from grains.[8] Small beer, also known as table beer or mild beer, which was highly nutritious, contained just enough alcohol to act as a preservative, and provided hydration without intoxicating effects. Small beer would have been consumed daily by almost everyone, including children, in the medieval world, with higher-alcohol ales served for recreational purposes. The lower cost for proprietors combined with the lower taxes levied on small beer led to the selling of beer labeled "strong beer" that had actually been diluted with small beer.[9] In medieval times, ale was likely safer to drink than most water (the germ theory of disease was unheard of, and the sterilizing properties of boiling unknown). The alcohol, hops, and some ingredients in gruit used to preserve some ales may have contributed to their lower load of pathogens, when compared to water. However, ale was largely safer due to the hours of boiling required in production, not the alcoholic content of the finished beverage.

Records from the Middle Ages show that ale was consumed in huge quantities. In 1272 a husband and wife who retired at Selby Abbey were given 2 gallons of ale per day with two loaves of white bread and one loaf of brown bread[10]. Monks at Westminster Abbey consumed 1 gallon of ale each day. In 1299, Henry de Lacy's household purchased an average of 85 gallons of ale daily and in 1385-6 Framlingham Castle consumed 78 gallons per day.[8]

Brewing ale in the Middle Ages was a local industry primarily pursued by women. Brewsters, or alewives, would brew in the home for both domestic consumption and small scale commercial sale. Brewsters provided a substantial supplemental income for families; however, only in select few cases, as was the case for widows, was brewing considered the primary income of the household.[11]

Modern ale

Ale is typically fermented at temperatures between 15 and 24 °C (60 and 75 °F). At temperatures above 24 °C (75 °F) the yeast can produce significant amounts of esters and other secondary flavour and aroma products, and the result is often a beer with slightly "fruity" compounds resembling those found in fruits, such as apple, pear, pineapple, banana, plum, cherry, or prune.

Varieties of ale

Brown ale

Brown ales tend to be lightly hopped, and fairly mildly flavoured, often with a nutty taste. In the south of England they are dark brown, around 3-3.6% alcohol, and quite sweet and palatable; in the north they are red-brown, 4.5-5% and somewhat drier. English brown ales first appeared in the early 1900s, with Manns Brown Ale and Newcastle Brown Ale as the best-known examples. The style became popular with homebrewers in North America in the early 1980s; Pete's Wicked Ale is an example.

Pale ale

Pale ale was a term used for beers made from malt dried with coke.[12] Coke had been first used for roasting malt in 1642, but it wasn't until around 1703 that the term pale ale was first used. By 1784 advertisements were appearing in the Calcutta Gazette for "light and excellent" pale ale. By 1830 onward the expressions bitter and pale ale were synonymous. Breweries would tend to designate beers as pale ale, though customers would commonly refer to the same beers as bitter. It is thought that customers used the term bitter to differentiate these pale ales from other less noticeably hopped beers such as porter and mild. By the mid to late 20th century, while brewers were still labelling bottled beers as pale ale, they had begun identifying cask beers as bitter, except those from Burton on Trent, which are often called pale ales regardless of the method of dispatch.

India Pale Ale (IPA)

In the nineteenth century, the Bow Brewery in England exported beer to India, including a pale ale that benefited from the duration of the voyage and was highly regarded among consumers in India. To avoid spoilage, Bow and other brewers added extra hops as a natural preservative. This beer was the first of a style of export ale that became known as India Pale Ale or IPA.

Golden ale

Developed in hope of winning the younger people away from drinking lager in favour of cask ales, it is quite similar to pale ale yet there are some notable differences—it is paler, brewed with lager or low temperature ale malts and it is served at colder temperatures. The strength of golden ales varies from 3.5% to 5.3%.[13]

Scotch ales

While the full range of ales are produced in Scotland, the term Scotch ale is used internationally to denote a malty, strong ale, amber-to-dark red in colour. The malt may be slightly caramelised to impart toffee notes; generally, Scottish beers tend to be sweeter, darker, and less hoppy than English beers. The classic styles are Light, Heavy and Export, also referred to as 60/-, 70/- and 80/- (shillings) respectively, dating back to the 19th-century method of invoicing beers according to their strength.[14]

Barley wine

Barley wines range from 6% to 12%, with some stored for long periods of time, about 18 to 24 months. While drinking barley wine, one should be prepared to taste "massive sweet malt and ripe fruit of the pear drop, orange and lemon type, with darker fruits, chocolate and coffee if darker malts are used. Hop rates are generous and produce bitterness and peppery, grassy and floral notes".[15]

Mild ale

Mild ale originally meant unaged ale, the opposite of old ale. It can be any strength or colour, although most are dark brown and low in strength, typically between 3 and 3.5%. An example of a lighter coloured mild is Banks's Mild.

Burton ale

Burton ale is a strong, dark, somewhat sweet ale, sometimes used as stock ale for blending with younger beers. Bass No.1 was a classic example of Burton ale. Some consider Fullers 1845 Celebration Ale a rare modern example of a Burton ale.[16]

Old ale

In England, old ale was strong beer traditionally kept for about a year, gaining sharp, acidic flavours as it did so. The term is now applied to medium-strong dark beers, some of which are treated to resemble the traditional old ales. In Australia, the term is used even less discriminately, and is a general name for any dark beer.

Belgian ales

Belgium produces a wide variety of speciality ales that elude easy classification. Virtually all Belgian ales are high in alcoholic content but relatively light in body due to the substitution of sucrose for part of the grist, which provides an alcohol boost without adding unfermentable material to the finished product. This process is often said to make a beer more digestible.

Cask ale

Cask ale is unfiltered and unpasteurised beer which is conditioned (including secondary fermentation) and served from a cask without additional nitrogen or carbon dioxide pressure. Cask ale is also sometimes referred to as real ale in the United Kingdom.

See also

- Aleberry, a beverage made by boiling ale with spice

- Beer measurement, information on measuring the colour, strength, and bitterness of beer

- Beer style

- Spiced ale

- Strong ale

References

- Ben McFarland, World's Best Beers: One Thousand Craft Brews from Cask to Glass. Sterling Publishing Company. 2009. p. 271. ISBN 978-1-4027-6694-7. Retrieved 7 August 2010.

- M. Shafiur Rahman, Handbook of Food Preservation. CRC Press. 2007. p. 221. ISBN 978-1-57444-606-7. Retrieved 7 August 2010.

- "Oxford English Dictionary Online". Retrieved 6 October 2014.

- Doorman, Gerard (1955). "De middeleeuwse brouwerij en de gruit /". lib.ugent.be. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- "ale (n.)". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- William Dwight Whitney, The Century Dictionary: An Encyclopedic Dictionary of the English Language vol. 1

- Food and eating in medieval Europe. Carlin, Martha., Rosenthal, Joel Thomas, 1934-. London: Hambledon Press. 1998. ISBN 978-0-8264-1920-0. OCLC 458567668.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Woolgar, Christopher Michael; Woolgar, C. M.; Serjeantson, D.; Waldron, T. (6 July 2006). Food in Medieval England: Diet and Nutrition. Oxford University Press. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-19-927349-2.

- Accum, Friedrich Christian. A treatise on adulterations of food: and culinary poisons, exhibiting the fraudulent sophistications of bread, beer, wine, spirituous liquors, tea, coffee ... and other articles employed in domestic economy and methods of detecting them. Longman, 1822, p. 159, p.170 read online

- Hallam,, H. E.; Thirsk, Joan (1988). The Agrarian History of England and Wales: Volume 2, 1042-1350. Cambridge University Press. p. 826. ISBN 9780521200738. Retrieved 21 July 2020.CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link)

- Bennett, Judith. Ale, Beer, and Brewsters in England. Retrieved 30 October 2012.

- Tomáš Hasík. The World of Beer and Beers of the World. thorium. p. 90.

- "Golden Ales". camra.org.uk. 2013. Archived from the original on 17 March 2013. Retrieved 25 March 2013.

- "Scottish Beers". camra.org.uk. 2013. Archived from the original on 17 March 2013. Retrieved 25 March 2013.

- "Barley Wines". camra.org.uk. 2013. Archived from the original on 17 March 2013. Retrieved 25 March 2013.

- Martyn Cornell Amber, Gold and Black p.52 The History Press 2010

External links

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Ale. |