Bnei Menashe

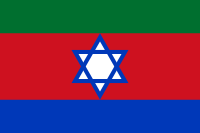

The Bnei Menashe (Hebrew: בני מנשה, "Children of Menasseh") are an ethnolinguistic group in India's North-Eastern border states of Manipur and Mizoram. Since the late 20th century, the Chin, Kuki, and Mizo peoples of this particular group claim descent from one of the Lost Tribes of Israel and have adopted the practice of Judaism.[2] In the late 20th century, Israeli rabbi Eliyahu Avichail, of the group Amishav, named these people the Bnei Menashe, based on their account of descent from Menasseh.[3] Most of the other residents of these two northeast states, who number more than 3.7 million and share their ethnic ancestry, do not identify with these claims.

| |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 10,000 according to Shavei Israel[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 7,000[1] | |

| 3,000[1] | |

| Languages | |

| Hmar, Gangte, Vaiphei, Kom, Lai, Paite Mara, Kuki, Simte, Mizo, Hebrew | |

| Religion | |

| Christianity - Judaism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Mizo, Hmar, Kuki, Zomi, Chin, Kachin, Shan and Karen. | |

Prior to conversion in the 19th century to Christianity by Welsh Baptist and Evangelical missionaries, the Chin, Kuki, and Mizo peoples were animists; among their practices was ritual headhunting.[4]

Most of those who now identify as Bnei Menashe had converted to Christianity. But in 1951, one of their tribal leaders reported having a dream that his people's ancient homeland was Israel.[5] Since the late 20th century, some of these peoples have begun embracing the idea that they were Jews, while keeping the belief that Jesus is the Messiah. The Bnei Menashe are a small group who started studying and practicing Judaism since the 1970s in a desire to return to what they believe is the religion of their ancestors. The total population of Manipur and Mizoram is more than 3.7 million. The Bnei Menashe are estimated by Shavei Israel to number around 10,000; close to 3,000 have emigrated to Israel.

In 2003–2004 DNA testing showed that several hundred men of this group had no evidence of Middle Eastern ancestry. A Kolkata study in 2005, which has been criticized, suggested that a small number of women sampled may have some Middle Eastern ancestry, but this may also have resulted from intermarriage during the thousands of years of migration of Jewish peoples.[4] In the early 21st century, Israel halted immigration by the Bnei Menashe; after a change in government, the immigration was allowed again. The chief rabbi of Israel ruled in 2005 that the Bnei Menashe were recognized as part of a lost tribe. After undergoing the process for formal conversion, they will be allowed aliyah (immigration).

History

Biblical background

In the time of the first temple, Israel was divided into two kingdoms. The southern one, known as the Kingdom of Judah, was made up mostly of the tribes of Judah, Benjamin and Levi. Most Jews today are descended from the southern kingdom. The northern Kingdom of Israel was made up of the remaining ten tribes. In approximately 721 B.C.E., the Assyrians invaded the northern kingdom, exiled the ten tribes living there, and enslaved them in Assyria (present-day Iraq).

Adoption of modern Judaism

According to Lal Dena, the Bnei Menashe have come to believe that the legendary Hmar ancestor Manmasi[6] was the Hebrew Menasseh, son of Joseph. During the 1950s, this group of Chin-Kuki-Mizo people began a Messianic movement. While believing that Jesus is the promised messiah for all Israelites, these pioneers in the early 1960s adopted observance of the Jewish Sabbath, holidays, dietary laws and other Jewish customs and traditions which they learned from books. They had no connections with other Jewish groups in the diaspora or in Israel. On May 31, 1972, some Messianic communities founded the Manipur Jewish Organization (later renamed United Jews Organization, NEI), the first Jewish organization in northeast India.

After these people did establish contacts with other Jewish religious groups in Israel and other countries, they began to practice more traditional rabbinic Judaism in the 1980s and 1990s. Rabbi Eliyahu Avichail is the founder of Amishav, an organization dedicated to finding the Lost Tribes and facilitating aliyah. He investigated this group's claims to Jewish descent in the 1980s. He named the group as the Bnei Menashe.[7][8]

In the late 20th century, many of the Bnei Menashe started studying normative Judaism. Hundreds emigrated to Israel, some completing the required formal conversions there in order to be accepted as Jews. Critics thought the government's policy of settling the Bnei Menashe immigrants in the unstable Judea, Samaria and Gaza Strip was part of a recruiting campaign to help increase Israel's population. Others criticised these people as economic migrants, and not true Jews. In 2005, the Chief Rabbinate of Israel accepted them as Jews due to the devotion displayed by their practice through the decades, but still required individuals to undergo formal ritual conversion to be accepted as Jews. Later that year, Israel began to refuse to issue visas to these peoples after India objected to Israeli teams entering the northeast states to perform mass conversions and arrange aliyah.

History of the Chin-Kuki-Mizo

Prior to their conversion to Christianity in the 19th century, the Chin-Kuki-Mizo practiced animism; ritual headhunting of enemies was part of their culture. Depending upon their affiliations, each tribe identifies primarily as Kuki, Mizo/Hmar, or Chin. The people identify most closely with their subtribes in the villages, each of which has its own distinct dialect and identity.[9] They are indigenous peoples, who had migrated in waves from East Asia and settled in what is now northeastern India. They have no written history but their legends refer to a beloved homeland that they had to leave, called Sinlung/Chinlung.[10] The various tribes speak languages that are branches of indigenous Tibeto-Burman.

Influence of revivalism

During the first Welsh missionary-led Christian Revivalism movement, which swept through the Mizo hills in 1906, the missionaries prohibited indigenous festivals, feasts, and traditional songs and chants. After missionaries abandoned this policy during the 1919–24 Revival, the Mizo began writing their own hymns, incorporating indigenous elements. They created a unique form of syncretic Christian worship. Christianity has generally been characterized by such absorption of elements of local cultures wherever it has been introduced.[11]

Dr. Shalva Weil, a senior researcher and noted anthropologist at Hebrew University, wrote in her paper, Dual Conversion Among the Shinlung of North-East (1965):

Revivalism (among the Mizo) is a recurrent phenomenon distinctive of the Welsh form of Presbyterianism. Certain members of the congregation who easily fall into ecstasy are believed to be visited by the Holy Ghost and the utterings are received as prophecies." (Steven Fuchs 1965: 16).[12]

McCall (1949) had recorded several incidents of revivalism, including the "Kelkang incident", in which three men "spoke in tongues", claiming to be the medium through which God spoke to men. Their following was large and widespread until they clashed with the colonial superintendent. He put down the movement and removed the "sorcery". (1949: 220–223).[13]

In a 2004 study Weil says, "although there is no documentary evidence linking the tribal peoples in northeast India with the myth of the lost Israelites, it appears likely that, as with revivalism, the concept was introduced by the missionaries as part of their general millenarian leanings."[14] In the 19th and 20th centuries, Christian missionaries "discovered" lost tribes in far-flung places; their enthusiasm for identifying such peoples as part of the Israelite tribes was related to the desire to speed up the messianic era and bring on the Redemption. Based on his experience in China, for example, Scottish missionary Rev. T.F. Torrance wrote China’s Ancient Israelites (1937), expounding a theory that the Qiang people were Lost Israelites.[15] This theory has not been supported by any more rigorous studies.

Some of the Mizo-Kuki-Chin say they have an oral tradition that the tribe traveled through Persia, Afghanistan, Tibet, China and on to India,[16] where it eventually settled in the northeastern states of Manipur and Mizoram.[17]

According to Tongkhohao Aviel Hangshing, leader of the Bnei Menashe in Imphal, the capital of Manipur, when the Bible was translated into local languages in the 1970s, the people began to study it themselves. Hangshing said, "And we found that the stories, the customs and practices of the Israeli people were very similar to ours. So we thought that we must be one of the lost tribes."[18] After making contact with Israelis, they began to study normative Judaism and established several synagogues. Hundreds of Mizo-Kuki-Chin emigrated to Israel. They were required to formally convert to be accepted as Jews, because their history was not documented. Also, given their long migration and intermarriage, they had lost the required maternal ancestry of Jews, by which they might be considered as born Jews.

Work of aliyah groups, Amishav and Shavei Israel

In the late 20th century, the Israeli Rabbi Eliyahu Avichail founded Amishav (Hebrew for "My People Returns"), an organisation dedicated to locating descendants of the lost tribes of Israel and assisting aliyah. In 1983 he first learned of the Messianic/Jewish group in northeastern India, after meeting Zaithanchhungi, an insurance saleswoman and former teacher who came from the area.[19] She had traveled to Israel in 1981 to present papers at seminars about her people's connection to Judaism.[20]

During the 1980s, Avichail traveled to northeast India several times to investigate the people's claims. He helped the people do research and collect historic documentation. The people were observed to have some practices similar to Judaism:[21]

- Three festivals annually similar to those of Jews

- Funeral rites, birth and marriage ceremonies have similarities to ancient Judaism

- Historical claim of descent from a great ancestor "Manmási", whose descriptions are similar to those of Manasseh, son of Joseph.

- Local legends, primarily those of the Hmar, that describe the presence of remnants of the lost Jewish tribe of Manasseh (Hebrew: Menashe) more than 1,000 years ago in a cave in southwestern China called Sinlung, whose members migrated across Thailand into northeastern India.

Believing that these people were descendants of Israelites, Avichail named the group Bnei Menashe. He began to teach them normative Orthodox Judaism. He prepared to pay for their aliyah with funds provided by Christian groups supporting the Second Coming. But the Israeli government did not recognize the Messianic groups in India as candidates for aliyah.

Several years later, the rabbi stepped aside as a leader of Amishav in favour of Michael Freund. The younger man was a columnist for The Jerusalem Post and former deputy director of communications and policy planning in the Prime Minister's office. The two men quarreled.

Freund founded another organization, Shavei Israel, also devoted to supporting aliyah by descendants of lost tribes. Each of the two men have attracted the support of some Bnei Menashe in Israel.[22] "Kuki-Mizo tribal rivalries and clans have also played a role in the split, with some groups supporting one man and some the other."[22] Freund uses some of his private fortune to support Shavei Israel. It has helped provide Jewish education for the Bnei Menashe in Aizawl and Imphal, the capitals of two northeast Indian states.[22]

In mid-2005, with the help of Shavei Israel and the local council of Kiryat Arba, the Bnei Menashe opened its first community centre in Israel. They have built several synagogues in northeast India. In July 2005, they completed a mikveh (ritual bath) in Mizoram under the supervision of Israeli rabbis. This is used in Orthodox Jewish practice and its use is required as part of the formal Orthodox process of conversion of candidates to Judaism.[23] Shortly after, Bnei Menashe built a mikveh in Manipur.

DNA testing results

Observers thought that DNA testing might indicate whether there was Middle Eastern ancestry among the Bnei Menashe. Some resisted such testing, acknowledging that their ancestors had intermarried with other peoples but saying that did not change their sense of identification as Jews.[24] In 2003 author Hillel Halkin helped arrange genetic testing of Mizo-Kuki peoples. A total of 350 genetic samples were tested at Haifa's Technion – Israel Institute of Technology under the auspices of Prof. Karl Skorecki. According to the late Isaac Hmar Intoate, a scholar involved with the project, researchers found no genetic evidence of Middle-Eastern ancestry for the Mizo-Chin-Kuki men.[25][26] The study has not been published in a peer-reviewed journal.

In December 2004, Kolkata's Central Forensic Science Laboratory posted a paper at Genome Biology on the Internet. This had not been peer reviewed. They tested a total of 414 people from tribal communities (Hmar, Kuki, Mara, Lai and Lusei) of the state of Mizoram. They found no evidence among the men of Y-DNA haplotypes indicating Middle Eastern origin. Instead, the haplotypes were distinctly East and Southeast Asian in origin.[21] In 2005, additional tests of MtDNA were conducted for 50 women from these communities. The researchers said they found some evidence of Middle Eastern origin, which may have been an indicator of intermarriage during the people's lengthy migration period.[27] While DNA is not used as a determinant of Jewish ancestry, it can be an indicator. It has been found in the Y-DNA among descendants in some other populations distant from the Middle East who claim Jewish descent, some of whose ancestors are believed to have been male Jewish traders.

Israeli Professor Skorecki said of the Kolkata studies that the geneticists "did not do a complete 'genetic sequencing' of all the DNA and therefore it is hard to rely on the conclusions derived from a "partial sequencing, and they themselves admit this."[28] He added

the absence of a genetic match still does not say that the Kuki do not have origins in the Jewish people, as it is possible that after thousands of years it is difficult to identify the traces of the common genetic origin. However, a positive answer can give a significant indication.[29]

BBC News reported, "[T]he Central Forensic Institute in Calcutta suggests that while the masculine side of the tribes bears no links to Israel, the feminine side suggests a genetic profile with Middle Eastern people that may have arisen through inter-marriage".[30] The social scientist Lev Grinberg commented that "right wing Jewish groups wanted such conversions of distant people to boost the population in areas disputed by the Palestinians."[30]

In November 2006, an Indian historian claimed to have found a genetic link between his Northern Indian Pathan clan and the Lost Tribe of Ephraim. Author Hillel Halkin said, "[T]here's no such thing as Jewish DNA. There is a [genetic] pattern which is very common in the Middle East, 40% of Jews worldwide have it and 60% do not have it. But many non-Jews and people in the Middle East have it also."[31]

Acceptance

In April 2005, the Sephardi Chief Rabbi Shlomo Amar, one of Israel's two Chief Rabbis, formally accepted the Bnei Menashe as descendants of one of the lost tribes after years of review of their claims and other research.[20] His decision allows the Bnei Menashe to immigrate as Jews to Israel under the country's Law of Return. But he requires them to undergo formal conversion to Judaism to be fully accepted as Jews, because of their long interruption from the people.

Most ethnic Mizo-Kuki-Chin have rejected the Bnei Menashe claim of Jewish origin; they believe their peoples are indigenous to Asia, as supported by the Y-DNA test results. Academics in Israel and elsewhere also have serious questions about any Jewish ancestry for this group.

By 2006, some 1,700 Bnei Menashe had moved to Israel, where they were settled in the West Bank and Gaza Strip (before disengagement). They were required to undergo Orthodox conversion to Judaism, including study and immersion in a mikveh. The immigrants were put in the settlements as these offered cheaper housing and living expenses than some other areas.[32] The Bnei Menashe composed the largest immigrant population in the Gaza Strip before Israel withdrew its settlers from the area.[33]

Learning Hebrew has been a great challenge, especially for the older generation, for whom the phonology of their native Indic and Tibeto-Burman languages makes Hebrew especially challenging. Younger members have had more opportunities to learn Hebrew, as they are more involved in society. Some have gained jobs as soldiers; others as nurses' aides for the elderly and infirm.[33]

Political issues in Israel and India

The mass conversions of Bnei Menashe after their immigration to Israel became controversial. In June 2003, Interior Minister Avraham Poraz of Shinui halted Bnei Menashe immigration to Israel. Shinui leaders had expressed concern that "only Third World residents seem interested in converting and immigrating to Israel."[34] In the previous decade, 800 Mizo had immigrated to Israel and converted to Judaism.

A group from Iquitos, Peru had immigrated in the late 20th century; they also had to undergo formal conversion. Some of the Peruvians were descended from male Sephardic Jews from Morocco who had gone to work in the city during its rubber boom in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. They had intermarried with Peruvian women, establishing families that gradually became assimilated as Catholic. In the 1990s, one descendant led an exploration and study of Judaism; eventually a few hundred adopted Jewish practices and converted before making aliyah to Israel.[34] (Another 150 immigrants came to Israel from Iquitos from 2013–2014; they were settled in Ramla as the others had been.)[35]

Ofir Pines-Paz, Minister of Science and Technology, said that the Bnei Menashe were "being cynically exploited for political purposes."[36] He objected to the new immigrants being settled in the unstable territory of the Gaza Strip's Gush Katif settlements (which were evacuated two years later) and in the West Bank. Rabbi Eliyahu Birnbaum, a rabbinical judge dealing with the conversion of Bnei Menashe, accused the Knesset Absorption Committee of making a decision based on racist ideas.[36] At the time, Michael Freund, with the Amishav organization, noted that assimilation was proceeding; young men of the Bnei Menashe served in Israeli combat units.[34]

The rapid rise in conversions also provoked political controversy in Mizoram, India. The Indian government believed that the conversions encouraged identification with another country, in an area already characterized by separatist unrest. Dr Biaksiama of the Aizawl Christian Research Centre said,

[T]he mass conversion by foreign priests will pose a threat not only to social stability in the region, but also to national security. A large number of people will forsake loyalty to the Union of India, as they all will become eligible for a foreign citizenship.

He wrote the book, Mizo Nge Israel? ("Mizo or Israeli?") (2004), exploring this issue.[37] He does not think the people have a legitimate claim to Jewish descent. Leaders of the Presbyterian Church in Mizoram, the largest denomination, have objected to the Israelis' activity there.

In March 2004, Dr Biaksiama appeared on television, discussing the issues with Lalchhanhima Sailo, founder of Chhinlung Israel People's Convention (CIPC), a secessionist Mizo organization.[38][39] Sailo said that CIPC's goal was not emigration to Israel, but to have the United Nations declare the areas inhabited by Mizo tribes to be an independent nation for Mizo Israelites.[40] The region has had numerous separatist movements and India has struggled to maintain peace there.

After Rabbi Amar's ruled in 2005 that the Bnei Menashe would be accepted as a lost tribe and Jews after completing conversion, the plan was for Bnei Menashe to undergo conversion while living in India, at which time they would be qualified for aliyah. In September 2005, a task force from the Chief Rabbinate's Beit Din (rabbinic court) traveled to India to complete the conversion of a group of 218 Bnei Menashe. India expressed strong concern to Israel about the mass conversions, saying its laws prohibit such interference by members of another nation. It wants to avoid proselytizing by outside groups and religious conflicts in its diverse society. In November 2005, the Israeli government withdrew the rabbinic court team from India because of the strained relations.

Some Bnei Menashe supporters said that Israeli officials failed to explain to the Indian government that the rabbis were formalizing the conversions of Bnei Menashe who had already accepted Judaism, rather than trying to recruit new members. Some Hindu groups criticised the Indian government, saying that it took Christian complaints about Jewish proselytizing more seriously than theirs. They have complained for years about Christian missionaries recruiting Hindus without receiving any governmental response.[41]

In July 2006, Israeli Immigration Absorption Minister Zeev Boim said that the 218 Bnei Menashe who had completed their conversions would be allowed to enter the country, but "first the government must decide what its policy will be towards those who have yet to (formally) convert."[42] A few months later, in November 2006, the 218 Bnei Menashe arrived in Israel and were settled in Upper Nazareth and Karmiel. The government has encouraged more people to settle in the Galilee and the Negev. The next year, 230 Bnei Menashe arrived in Israel in September 2007, having completed the formal conversion process in India.

In October 2007, the Israeli government said that approval of travelers' entry into Israel for the purpose of mass conversion and citizenship would have to be decided by the full Cabinet, rather than by the Interior Minister alone. This decision was expected to be a major obstacle in Shavei Israel's endeavours to bring all Bnei Menashe to Israel. The government suspended issuing visas to the Bnei Menashe.

In 2012, after a change in government, the Israel legislature passed a resolution to resume allowing immigration of Bnei Menashe. Fifty-four entered the country in January 2013, making a total of 200 immigrants, according to Shavei Israel.[17][43]

Legends

All of the folklore which supports the Bnei Menashe's Jewish ancestry are taken/found in Hmar history. One such is the traditional Hmar harvest festival (Sikpui Ruoi) song, "Sikpui Hla (Sikpui Song)," which refers to events and images similar to some in the Book of Exodus, is evidence of their Israelite ancestry. Studies of comparative religion, however, have demonstrated recurring motifs and symbols in unrelated religions and peoples in many regions.[44] In addition, other Mizo-Kuki-Hmar people say that this song is an ancient one of their culture. The song includes references to enemies chasing the people over a red-coloured sea,[45] quails, and a pillar of cloud.[45] Such images and symbols are not exclusive to Judaism.

Translation of the lyrics:[46]

While we are preparing for the Sikpui Feast,

The big red sea becomes divided;

As we march along fighting our foes,

We are being led by pillar of cloud by day,

And pillar of fire by night.

Our enemies, O ye folks, are thick with fury,

Come out with your shields and arrows.

Fighting our enemies all day long,

We march forward as cloud-fire goes before us.

The enemies we fought all day long,

The big sea swallowed them like wild beast.

Collect the quails,

And draw the water that springs out of the rock.

Michael Freund, the director of Shavei Israel, wrote that the Bnei Menashe claim to have a chant they call "Miriam's Prayer." By that time, he had been involved for years in promoting the Bnei Menashe as descended from Jews and working to facilitate their aliyah to Israel.[47] He said that the words of the chant were identical to the ancient Sikpui Song. The Post article is the first known print reference to Miriam's Prayer, aka "Sikpui Hla."[47]

Films

- Quest for the Lost Tribes. (2000) Directed by Simcha Jacobovici.

- Return of the Lost Tribe. Directed by Phillipe Stroun

- This Song Is Old[48] (2009), Directed by Bruce Sheridan

See also

References and notes

- Reback, Gedalyah. "3,000th Bnei Menashe touches down in Israel". Times of Israel. Retrieved 27 December 2018.

- Weil, Shalva. "Double Conversion among the 'Children of Menasseh'" in Georg Pfeffer and Deepak K. Behera (eds) Contemporary Society Tribal Studies, New Delhi: Concept, pp. 84–102. 1996 Weil, Shalva. "Lost Israelites from North-East India: Re-Traditionalisation and Conversion among the Shinlung from the Indo-Burmese Borderlands", The Anthropologist, 2004. 6(3): 219–233.

- Fishbane, Matthew (19 February 2015). "Becoming Moses". Tablet Magazine. Retrieved 2 May 2016.

- Asya Pereltsvaig (9 June 2010), Controversies surrounding Bnei Menashe, Languages of the World

- https://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=127241410

- Dena, Lal (26 July 2003). "Kuki, Chin, Mizo – Hmar's Israelite Origin; Myth or Reality?". Manipur Online. Archived from the original on 2 February 2007. Retrieved 4 March 2007.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 3 May 2016. Retrieved 25 June 2015.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "The politics of 'Lost Tribe'". Grassroots Options. Archived from the original on 25 March 2007. Retrieved 4 March 2007.

- Ling, Salai Za Uk. "The Role of Christianity in Chin Society" (PDF). Chin Human Rights Organization. Retrieved 4 March 2007. Weil, Shalva. "Dual Conversion Among the Shinlung of North-East India," Studies of Tribes and Tribals 1(1): 43–57 (inaugural volume). 2003.

- "Mizoram History". Mizoram State Centre. Retrieved 4 March 2007.

- Sebastian Chang-Hwan Kim. "'Showers of Blessing': Revival Movements in the Khassia Hilss and Mukti Mission in Early Twentieth-Century India" (PDF). Retrieved 4 March 2007.

- Weil, Shalva. "Dual Conversion Among the Shinlung of North-East India", Studies of Tribes and Tribals, 2003. 1(1): 43–57 (inaugural volume).

- Weil, Shalva. "Lost Israelites from North-East India: Re-Traditionalisation and Conversion among the Shinlung from the Indo-Burmese Borderlands." The Anthropologist, 2004, 6(3): 219–233.

- Torrance, Rev. TF (1937). China’s Ancient Israelites.

- Weil, Shalva. (1991) Beyond the Sambatyon: the Myth of the Ten Lost Tribes. Tel-Aviv: Beth Hatefutsoth, the Nahum Goldman Museum of the Jewish Diaspora.

- "Israel takes in more Bnei Menashe 'lost tribe' members", BBC, 25 December 2012, accessed 8 May 2013

- Geeta Pandey, "India's lost Jews' wait in hope", BBC, 18 August 2004, accessed 8 May 2013

- Fathers, Michael (6 September 1999). "Lost Tribe of Israel?". Time Asia. Retrieved 4 March 2007.

- "Rabbi backs India's 'lost Jews'". BBC News. 1 April 2005. Retrieved 3 March 2007.

- Bhaswar Maity, T. Sitalaximi, R. Trivedi, and V. K. Kashyap, "Tracking The Genetic Imprints of Lost Jewish Tribes Among The Gene Pool of Kuki-Chin-Mizo Population of India", December 2004, posted at Genome Biology (not peer-reviewed), accessed 8 May 2013

- Linda Chhakchhuak (2006). "Interview with Hillel Halkin". grassrootsoptions. Archived from the original on 25 March 2007. Retrieved 3 March 2007.

- Peter Foster (17 September 2005). "India's lost tribe recognised as Jews after 2,700 years" (XML). The Telegraph (UK). London. Retrieved 3 March 2007.

- Inigo Gilmore, "Indian 'Jews' Resist DNA Tests to Prove They Are a Lost Tribe", The Telegraph (London), 10 November 2002

- Isaac Hmar, "The Jewish Connection: Myth or Reality", E-Pao

- "The lost and found Jews in Manipur and Mizoram", E-Pao

- Tathagata Bhattacharya (12 September 2004). "DNA tests prove that Mizo people are descendants of a lost Israeli tribe". This Week. Archived from the original on 1 January 2007. Retrieved 3 March 2007.

- [http://www.haaretz.com/in-search-of-jewish-chromosomes-in-india-1.154733 Yair Sheleg, "In Search of Jewish Chromosomes in India", Haaretz, 1 April 2005

- Tudor Parfitt; Yulia Egorova (2006). Genetics, Mass Media And Identity: A Case Study of the Genetic Research on the Lemba And Bene Israel. Taylor & Francis. p. 124. ISBN 978-0-415-37474-3. Retrieved 25 December 2012.

- "Rabbi backs India's 'lost Jews'", BBC News, 1 April 2005.

- , Jerusalem Post, November 2006

- "More than 200 Bnei Menashe arriving in Israel", Israel National News

- Harinder Mishra (21 November 2006). "Exodus of Indian Jews from north-east to Israel". rediff news. Retrieved 3 March 2007.

- Abigail Radoszkowicz, "Bnei Menashe aliya halted by Poraz", The Jerusalem Post, 7 August 2003, hosted at Shavei.org, accessed 8 May 2013

- Zohar Blumenkrantz and Judy Maltz, "New Group of 'Amazon Jews' Arrives in Israel", Haaretz, 14 July 2013, accessed 19 August 2015

- Arutz Sheva Archived 1 November 2005 at the Wayback Machine

- David M. Thangliana (26 October 2004). "New Book X-Rays 'Baseless' Mizo Israel Identity". farshores.org. Retrieved 3 March 2007.

- Simon Says (15 February 2004). "Mizoram: A State of Israel in South East Asia". TravelBlog. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 2007-03-03.

- Simon Says (19 December 2004). "An emerging Israel in Mizoram". TravelBlog. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 2007-03-03.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 19 July 2011. Retrieved 18 June 2006.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Surya Narain Saxena (15 January 2006). "UPA Government goes out to help conversion". Organiser.org. Archived from the original on 27 May 2011. Retrieved 3 March 2007.

- Hilary Leila Kreiger (2 July 2006). "Bnei Menashe aliya, conversions halted pending government review". Jerusalem Post. Archived from the original on 11 May 2011. Retrieved 2007-03-03.

- "2000th Bnei Menashe immigrant arrives in Israel", Jerusalem Post (JPost), 14 January 2013, accessed 8 May 2013

- Mircea Eliade, Image and Symbol

- Hmar, Isaac L (8 August 2005). "Mizo-Kuki's Claim of Their Jewish Origin: Its impact on Mizo society". E-Pao. Retrieved 4 March 2007.

- Zoram, archived from the original on 21 October 2007

- "Echoes of Egypt in India", Jerusalem Post. Retrieved 2014-12-01.

- https://web.archive.org/web/20140714124336/http://theloop.colum.edu/s/644/newsletter.aspx?sid=644&gid=1&pgid=252&cid=11036&ecid=11036&ciid=40258&crid=0

Further reading

- Hillel Halkin, Beyond the Sabbath River (2002)

- Zaithanchhungi, Zaii. Israel-Mizo Identity: Mizos (Chhinlung Tribes) Children of Menashe are the Descendants of Israel. Mizoram: L.N. Thuanga "Hope Lodge", 2008.

- Weil, Shalva. "Ten Lost Tribes", in Raphael Patai and Haya Bar Itzhak (eds.) Jewish Folklore and Traditions: A Multicultural Encyclopedia, ABC-CLIO, Inc. 2013, (2: 542–543).