Gush Katif

Gush Katif (Hebrew: גוש קטיף, lit. Harvest Bloc) was a bloc of 17 Israeli settlements in the southern Gaza strip. In August 2005, the Israeli army carried out the Cabinet's decision and forcibly removed the 8,600 residents of Gush Katif from their homes. Their communities were demolished as part of Israel's unilateral disengagement from the Gaza Strip.

Geography

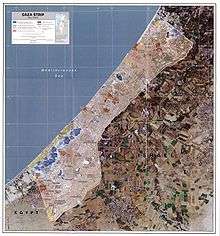

Gush Katif was located on the southwestern edge of the Gaza Strip, bordered on the southwest by Rafah and the Egyptian border, on the east by Khan Yunis, on the northeast by Deir el-Balah, and on the west and northwest by the Mediterranean Sea. A narrow one kilometer strip of land populated by Bedouins known as al-Mawasi lay along the Mediterranean coast. Most of Gush Katif was situated on the sand dunes that separate the coastal plain from the sea along much of the southeastern Mediterranean.

Two roads served the residents of Gush Katif: Road 230, which runs from the southwest along the sea from the Egyptian border at Rafiah Yam through Kfar Yam to Tel Katifa on the bloc's northern border, where it entered Palestinian-controlled territory, and Road 240, which also runs parallel to the sea approximately one kilometre inland, and upon which the majority of the settlements and traffic were located. Road 240's southern end turned south to reach Morag and continued to Sufah and the Shalom bloc of villages south of the Gaza Strip, while its northern end turned east to the Kissufim junction, and served as the main route into Gush Katif. These roads were forbidden to Palestinian Arab drivers.

While Kfar Darom and Netzarim were originally accessed along the main road to Gaza (known as "Tencher Road"), Israeli and Palestinian traffic was separated after the Oslo Accords and the escalation in Arab terror. Netzarim was isolated as an enclave accessed only through the Karni crossing and the Sa'ad junction and in the latter years, only by IDF armored vehicles. In 2002, a bridge was built for Road 240 over the Tencher road so as to physically separate the two arteries and allow unobstructed travel for both Palestinian and Israeli traffic.

Demographics

About 8,600 residents lived in Gush Katif,[1] many of them Orthodox Religious Zionist Jews, though many non-observant and secular Jews also called it home. The three northernmost communities: Nisanit, Dugit and Rafiah Yam were secular. The area also included several hundred Muslim families, mostly of the al-Mawasi Bedouin community, who while technically Palestinian residents, were able to enjoy freedom of movement within the Israeli areas due to their peaceful relations. Contrary reports have noted the severity of the restriction of movement for Palestinian residents.[2]

History

Jews and their Israelite ancestors have lived in Gaza since Biblical times. Famed residents include medieval rabbis Rabbi Yisrael Najara, author of Kah Ribon Olam, the popular Shabbat song, and renowned Mekubal Rabbi Avraham Azoulai.[3] A historic Jewish community existed in Gaza City prior to its expulsion for safety reasons by the British during the infamous 1929 riots by the city's Arabs. Land for the village of Kfar Darom was purchased in the 1930s and settled in 1946. It was evacuated following an Egyptian siege in the 1948 Arab-Israeli War.

Gush Katif began in 1968, when Yigal Allon presented an initiative for the founding of two Nahal settlements in the center of the Gaza Strip. He viewed the breaking of the continuity between the northern and southern Arab settlements as vital to Israel's security in the area, which had been captured the previous year in the 1967 Six-Day War. In 1970, Kfar Darom was reestablished as the first of many Israeli agricultural villages in the area. Allon's idea was ultimately designed with five key areas (or 'fingers,' thus being called by some the "five-finger print") slated for Israeli presence along the length of the Gaza Strip. After the Egypt–Israel Peace Treaty and the dismantling of the fifth 'finger' (Yamit bloc) south of Rafah, the fourth (Morag) and third (Kfar Darom) strips were united into one bloc that would become known as Gush Katif. The second finger, Netzarim, was very much connected to Gush Katif until the arrangements following the Oslo Accords, while the bloc on the dunes north of Gaza, which straddled the Green Line, was more a part of the Ashkelon area communities.[4]

Throughout the 1980s new communities were established, especially with the influx of former residents of the Sinai. Most of the bloc's communities were established as agricultural cooperatives called moshavs, where the residents from each town would work in clusters of greenhouses just outside the residential areas.

Economy

In the Katif Bloc's greenhouses, advanced technology was used to grow pest-free leafy vegetables and herbs answering to the strictest health, aesthetic and religious requirements. Most of the organic agricultural products were exported to Europe. In addition, the community of Atzmona had Israel's largest plant nursery, and with 800 cows, the Katif dairy was the second largest in the country. Telesales and printing were other notable industries.

The sum of exports from the greenhouses of Gush Katif, which were owned by 200 farmers,[5] came to $200,000,000 per year[6] and made up 15% of the agricultural exports of the State of Israel.[7]

The combined assets in Gush Katif were estimated at $23 billion.[8]

Of Israel's total exports abroad, Gush Katif exported:

- 95% of bug-free lettuce and greens[9]

- 70% of organic vegetables[9]

- 60% of cherry tomatoes[9]

- 60% of geraniums to Europe.[9]

The Economic Cooperation Foundation, which is funded by the European Union, agreed to purchase the greenhouses for $14 million and transfer ownership to the Palestinian Authority, so that the 4,000 Palestinians employed to work in them could keep their jobs.The money was paid for the greenhouse guts, such as the computerized irrigation systems, as the law in Israel only allowed for the government to pay for the land and structures, as these are not moveable.[10] Israel compensated the evacuees 55 million dollars for the greenhouses and the land.[10] Former head of the World Bank, James Wolfensohn, contributed $500,000 of his own money to the project.[11] The rest was contributed by a group of prominent Jewish philanthropists, including Mortimer Zuckerman, Lester Crown and Leonard Stern. They bought the irrigation systems and other moveables, because, according to Zuckerman, "Without those, the Palestinians would not be able to make a go of running the greenhouses."[10]

When the IDF left Gaza, half of Gaza's greenhouses were dismantled by their owners before leaving. The owners despaired at the time of receiving compensation, so they removed what they could.[12] Afterwards Palestinians looted the area, and 800 of the 4,000 greenhouses were left unusable,[13][14] while, according to Wolfensohn, most were left intact.[15] Subsequently, the harvest, intended for export via Israel for Europe, was essentially lost due to the Israeli restrictions on the Karni crossing which "was closed more than not", leading to losses in excess of $120,000 per day.[15] Economic consultants estimated that the closures cost the whole agricultural sector in Gaza $450,000 a day in lost revenue.[16] Israel closed the crossing due to security concerns.

Palestinian attacks

Although the Gush Katif settlements and the roads leading to it were guarded by the Israeli Army's Gaza Division, settlers were still vulnerable to attacks.

During the First Intifada (1987–1990), which broke out in nearby Gaza, the residents of Gush Katif were on the forefront of the violence and were subject to frequent stoning of traffic, among other incidents.

Since the beginning of the al-Aqsa Intifada (2000), Gush Katif settlements were the target of thousands of violent attacks by Palestinian militants. More than 6000 mortar bombs and Qassam rockets were launched into Gush Katif, miraculously causing only few fatalities though tremendous property and psychological damage and heavy shock and fear.[17][18] Most of the ground attacks were infiltrations and shootings. There were also attempts to infiltrate by sea. Victims include Itamar Yefet (18), who was shot and killed by a Palestinian sniper in November 2000.[19] Arik Krogliak, Tal Kurtzweil, Asher Marcus, Eran Picard, and Ariel Zana, all teenagers, were fatally shot in March 2002 when terrorists infiltrated the "Otzem" pre-military academy in Atzmona.[19]

Palestinian attacks on Israeli vehicles traveling on the Kissufim road were very common. In one of these attacks, in May 2004, Palestinian militants ambushed and killed Tali Hatuel, who was eight months pregnant, and her four daughters: Hila (11), Hadar (9), Roni (7), Merav (2).[20][21][22] Ahuva Amergi (30) was killed when a Palestinian terrorist opened fire on her car, along with two soldiers who came to her assistance in February 2002.[19] In another, a school bus was bombed on 20 November 2000,[23] leaving Miriam Amitai (35) and Gavriel Biton (34) dead and several maimed children. Three children from the Cohen family lost their legs in the attack.[24] Many of the ground attacks on Gush Katif were thwarted by the Israeli military.

In January 2002, Oded Sharon (36) was killed in a suicide bombing.[19]

Controversy

Gush Katif's location within the greater Gaza Strip was for many a source of controversy.

Its location was initially the main reason for its founding, as an Israeli civilian presence was important for cementing control of the area so as to prevent any future invasion from Egypt or its use as a staging area for fedayeen attacks, and indeed this rationale was echoed following the 1967 Six-Day War by the US Joint Chiefs of Staff.[25]

Evacuation

.jpg)

On August 13, 2005, the Gush Katif region was closed to non-residents, in keeping with the plan to evacuate the Katif bloc. Though effectively violating the Disengagement law, which most residents viewed as highly immoral and illegitimate,[26] most settlers did not voluntarily leave their homes or even pack in preparation for the eviction. On August 15, 2005, the forcible evacuation of the Gush Katif settlements began. On August 22, 2005, the residents of the last settlement, Netzarim, were evicted. In essence, many residents returned to pack the contents of their homes and the Israeli government began the destruction of all residential buildings. On September 12, 2005, the Israeli Army withdrew from each settlement up to the Green Line. All public buildings (schools, libraries, community centres, office buildings) as well as industrial buildings, factories, and greenhouses which could not be taken apart were left intact.

Originally, the Israeli cabinet had planned to destroy synagogues in the settlement, but the government caved in to pressure from religious Jewish organizations and reversed its decision.[27][28] However, most of the synagogues were destroyed by Palestinian mobs immediately after the evacuation. Abu Abir, a member of the Popular Resistance Committees terrorist organization, commented that "The looting and burning of the synagogues was a great joy...It was in an unplanned expression of happiness that these synagogues were destroyed." Later, in 2007, it was reported that "The ruins of two large synagogues in Gush Katif, the evacuated Jewish communities of the Gaza Strip, have been transformed into a military base used by Palestinian groups to fire rockets at Israeli cities and train for attacks against the Jewish state, according to a senior terror leader in Gaza."[29]

Aftermath

Controversy in Israel

The action proved controversial inside Israel. The settlers, backed by the right-wing, as shown in the Likud referendum, claimed Israel had a historic right to the land and that they provided an important defense buffer against attacks by Palestinians. The conservative government of Prime Minister Ariel Sharon argued that remaining in Gaza was too costly in both money and lives.

Sharon's withdrawal did not advance the peace process because, from the Palestinian perspective, the unilateral pullout took place without negotiation on wider issues affecting both sides. NPR addressed this issue in a Q&A about Israel's pullout from Gaza.[30]

History after Israeli withdrawal

After the Israeli withdrawal of settlers, the Palestinian Authority took control of Gaza. On January 25, 2006, Hamas won parliamentary elections in both Gaza and the West Bank. Israel, the U.S. and a number of European governments refused to recognize Hamas’ election victory and imposed an economic blockade on Gaza. During June 2007, an internal civil conflict between Hamas and Fatah resulted in Hamas taking control of the Gaza Strip, while Fatah ruled the West Bank.[31]

In May 2011 both parties agreed to reconstitute a united Palestinian government and hold elections by May 2012.[32]

In July 2014 Israel experienced the effects of the disengagement and Hamas coming to power which resulted in Operation Protective Edge as Israel sought to protect its residents from the barrage of rockets fired from Gaza; destroyed a network of tunnels aimed at Israel's southern communities; and targeted Hamas bases some of which were located where Gush Katif once stood.[33] Many politicians and journalists realized the connection between the Israeli 2005 withdrawal and the Hamas takeover. Some even apologised for not realizing this would happen and doing enough to prevent it.[34]

Former Gush Katif land today

At the time of the Gush Katif withdrawal, Israeli authorities destroyed all the Jewish residents' homes. Palestinians dismantled most of what remained, scavenging for cement, rebar and other construction materials. There had been an intense public conflict regarding the many public structures and synagogues in Gush Katif. "Many asserted that the buildings must be destroyed in order to ensure that they would not be used by terrorist organizations in the future. The fate of many of the area’s synagogues was also discussed at that time".[35] Initially, the government favoured demolition of the synagogues and was adamant that the high courts should not intervene. However, later they changed their mind. "Limor Livnat suggested involving UNESCO, with the hopes they would declare Gush Katif synagogues as official World Heritage Sites".[35] The synagogues were left intact, as the IDF did not wish to destroy holy sites and hoped that the Palestinians would respect these buildings. However, the Palestinians set fire to the buildings.[36]

Settlements in Gush Katif

- Bedolah בדולח (lit. Crystal)

- Bnei Atzmon בני עצמון (named after the Atzmona community in Sinai)

- Gadid גדיד (lit. picking of palm tree fruits)

- Gan Or גן אור (lit. Garden of light)

- Ganei Tal גני טל (lit. Gardens of dew)

- Kfar Darom כפר דרום (lit. South village)

- Kfar Yam כפר ים (lit. Village of the sea)

- Kerem Atzmona כרם עצמונה

- Morag מורג (lit. Harvest scythe)

- Neve Dekalim נוה דקלים (lit. Palm tree Oasis)

- Netzer Hazani נצר חזני (named after Cabinet Minister Michael Hazani)

- Pe'at Sade פאת שדה (lit. the edge of the field)

- Katif קטיף (lit. harvest, picking of flowers)

- Rafiah Yam רפיח ים

- Shirat Hayam שירת הים (lit. Song of the sea)

- Slav שליו (lit. Quail)

- Tel Katifa תל קטיפא

Most of the Gush Katif settlements were concentrated in one block on the southwest edge of the Gaza Strip and were individually surrounded by fencing.

Settlements north of Gush Katif

- Dugit דוגית (small boat)

- Elei Sinai אלי סיני (named after Sinai)

- Nisanit ניסנית (a flower that blossoms in the sands)

- Netzarim נצרים (lit. scions)

The three Israeli settlements on the northern edge of the Gaza Strip (Elei Sinai, Dugit and Nisanit), and another near its center (Netzarim) were more detached. The three former used Ashkelon services while Netzarim was mostly self-sufficient.

See also

References

- Foundation for Middle East Peace, "Settlements in the Gaza Strip" Archived May 12, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- "Al-Mawasi, Gaza Strip: Impossible Life in an Isolated Enclave, March 2003". B'tslem. B'tslem. Retrieved 16 January 2015.

- "History of Jewish Settlements in Gaza".

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2007-03-11. Retrieved 2006-12-08.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Israel Transfers Gush Katif Hothouses to Palestinians (September 2005)".

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2014-08-26. Retrieved 2014-08-25.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Gush Katif: Past and Future".

- "A thousand brides - Opinion - Jerusalem Post".

- "PA Farmers in Gaza: How do Those Israelis do It?".

- Newman, Andy (2005-08-18). "How Old Friends of Israel Gave $14 Million to Help the Palestinians". The New York Times.

- Looters strip Gaza greenhouses

- Erlanger, Steven (2005-07-15). "Israeli Settlers Demolish Greenhouses and Gaza Jobs". The New York Times.

- "Palestinian Militants Ransack Former Gush Katif Greenhouses". Haaretz. 2006-02-10.

- "Israel Transfers Gush Katif Hothouses to Palestinians (September 2005)".

- Beinart, Peter (2014-07-30). "Gaza Myths and Facts: What American Jewish Leaders Won't Tell You". Haaretz.

- Wolfensohn, James D. (2010-10-12). A Global Life: My Journey Among Rich and Poor, from Sydney to Wall Street to the World Bank. ISBN 9781586489939.

- Q&A: Gaza conflict, BBC News 18-01-2009

- Gaza's rocket threat to Israel, BBC 21-01-2008

- "20 of 21 Gaza Settlements Evacuated". Washington Post. Retrieved 2008-06-30.

- "Israel/Occupied Territories: AI condemns murder of woman and her four daughters by Palestinian gunmen". Amnesty International. May 4, 2004.

- "Tali Hatuel, Hila, Hadar, Roni, and Merav". Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs. May 2, 2004.

- "Gaza Strip bomb targets school bus". The Guardian. 2000-11-20.

- Amputee children leave Kfar Darom

- "The Jewish Agency". Retrieved December 8, 2006.

- Dromi, Shai M. (2014). "Uneasy Settlements: Reparation Politics and the Meanings of Money in the Israeli Withdrawal from Gaza". Sociological Inquiry. 84 (1): 294–315. doi:10.1111/soin.12028.

- JOSEF FEDERMAN/Associated Press (September 11, 2005). "First Israeli Army Convoys Depart Gaza". Yahoo!. Archived from the original on November 21, 2018. Retrieved January 5, 2020.

- Associated Press (September 12, 2005). "Palestinians set Gaza synagogues on fire". Hindustan Times. Archived from the original on September 30, 2007.

- Synagogues now terror firing zone. Ynetnews. February 27, 2007.

- NPR Q&A https://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=4775357

- New York Times, June 14, 2007, https://www.nytimes.com/2007/06/14/world/middleeast/14mideast.html

- Washington Post https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/palestinian_factions_formally_sign_unity_accord/2011/05/04/AFD89MmF_story.html?wprss=rss_middle-east

- "Hamas Tests Improved Long-Range Missiles".

- "Knesset holds special plenary session marking 9 years since Gaza disengagement". The Knesset. July 16, 2014. Retrieved 8 August 2014.

- "Hamas using Gush Katif synagogues to train gunmen". 2008-07-15.

- "Memory of Gush Katif Synagogues".

- 2. Footnote <https://web.archive.org/web/20060512095055/http://www.fmep.org/settlement_info/stats_data/gaza_strip_settlements.html > There is no such article on this page.

Further reading

- The Gush Katif Heritage Center in Nitzan

- Map of Gaza Strip, showing settlements

- Gush Katif Committee official website (Hebrew), English version

- Virtual Tour of Gush Katif

- The Gaza Strip Jewish Virtual Library

- Jewish Settlements, Outposts Expanding Despite Pledges Growth Most Striking in Gaza Strip, Report Says, By John Ward Anderson, Washington Post Foreign Service, Friday, July 23, 2004; Page A26

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Gush Katif. |

- Yad-Katif—Gush Katif Memorial—Videos, songs and thousands of photos

- Data published by the UN in 2010.

- Pullout Plans discussed in 2012

- Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting http://pulitzercenter.org/projects/arab-spring-gaza-egypt-mubarak-tahrir-square