Names of the Romani people

The Romani people are also known by a variety of other names; in English as gypsies or gipsies (seen by some as a slur, as discussed below) and Roma, in Greek as γύφτοι (gíftoi) or τσιγγάνοι (tsiggánoi), in Central and Eastern Europe as Tsingani (and variants), in France as gitans besides the dated bohémiens, manouches, in Italy as zingari and gitani, in Spain as gitanos, and in Portugal as ciganos.

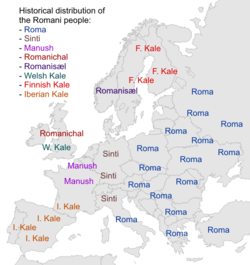

Self-designation also varies: In Central and Eastern Europe, Roma is common. The Romani of England call themselves (in Angloromani) Romanichal, those of Scandinavia (in Scandinavian romanidialect) Romanisæl. In German-speaking Europe, the self-designation is Sinti, in France Manush, while the groups of Spain, Wales and Finland use Kalo/Kale (from kalo meaning "black" in Romani language). There are numerous subgroups and clans with their own self-designations, such as the Kalderash, Machvaya, Boyash, Lovari, Modyar, Xoraxai, Lăutari, etc.

In the English language (according to OED), Rom is a noun (with the plural Romá or Roms) and an adjective, while Romany is also a noun (with the plural Romanies) and an adjective. Both Rom and Romany have been in use in English since the 19th century as an alternative for Gypsy. Romany is also spelled Romani, or Rommany.[1][2][3][4][5]

Sometimes, rom and romani are spelled with a double r, i.e., rrom and rromani, particularly in Romania in order to distinguish from the Romanian endonym (români). This is well established in Romani itself, since it represents a phoneme (/ʀ/ also written as ř and rh) which in some Romani dialects has remained different from the one written with a single r.[6]

Roma is a term primarily used in political contexts to refer to the Romani people as a whole.[7][8] Still, some subgroups of Romani do not self-identify as Roma, therefore some scholars avoid using the term Roma as not all Romani subgroups accept the term.[9]

Because all Romanies use the word Romani as an adjective, the term began to be used as a noun for the entire ethnic group.[10]

Today, the term Romani is used by some organizations — including the United Nations and the US Library of Congress.[6] However, the Council of Europe and other organizations use the term Roma to refer to Romani people around the world, and recommended that Romani be restricted to the language and culture: Romani language, Romani culture.[11][12][13]

Etymology

The demonyms of the Romani people, Lom and Dom share the same etymological origin,[14][15] reflecting Sanskrit ḍoma "a man of low caste, living by singing and music"[16][17]

Gypsy and gipsy

The English term gipsy or gypsy[18] is commonly used to indicate Romani people, Tinkers and Travellers, and use of the word gipsy in modern-day English is so pervasive (and is a legal term under English law—see below) that some Romani organizations use it in their own organizational names. However—according to the few who study the Romani people and a large percentage of the Romani people—the word has been tainted by its use as a racial slur and a pejorative connoting illegality and irregularity,[19][20][21][22][23][24][25] and some modern dictionaries either recommend avoiding use of the word gypsy entirely or give it a negative or warning label.[26][27][28][29][30][31]

The Oxford English Dictionary states a 'gipsy' is a

member of a wandering race (by themselves called Romany), of Indian origin, which first appeared in England about the beginning of the 16th c.

According to the OED, the word was first used in English in 1514, with several more uses in the same century, and both Edmund Spenser and William Shakespeare used this word.[32]

This exonym is sometimes written with a capital letter, to show that it designates an ethnic group.[33] The Spanish term gitano, the French term gitan and the Basque term ijito have the same origin.[34]

During the 16th and 17th centuries, the name was written in various ways: Egipcian, Egypcian, 'gypcian. The word gipsy/gypsy comes from the spellings which had lost the initial capital E, and that is one reason that it is often spelled with the initial g in lowercase.[35] As time elapsed, the notion of 'the gipsy/gypsy' altered to include other associated stereotypes such as nomadism and exoticism.[36] John Matthews in The World Atlas of Divination refer to gypsies as "Wise Women."[37] Colloquially, gipsy/gypsy is used refer to any person perceived by the speaker as fitting the gypsy stereotypes.[38]

Use in English law

Gipsy has several developing and overlapping meanings under English Law. Under the Caravan Sites and Control of Development Act 1960, gipsies are defined as "persons of nomadic habit of life, whatever their race or origin, but does not include members of an organised group of travelling showmen, or persons engaged in travelling circuses, travelling together as such".[39] The definition includes such groups as New Age Travellers as well as Irish Travellers and Romany.[40][41]

Gipsies of Romany origins have been a recognised ethnic group for the purposes of Race Relations Act 1976 since Commission for Racial Equality v Dutton 1989 and Irish Travellers in England and Wales since O'Leary v Allied Domecq 2000 (having already gained recognition in Northern Ireland in 1997).[42]

List of names

Tsinganoi

In much of continental Europe, Romanies are known by names related to the Greek term τσιγγάνοι (tsinganoi):

| Slavic | Germanic | Romance | Other |

|---|---|---|---|

|

The name originates with Byzantine Greek ἀτσίγγανοι (atsinganoi, Latin adsincani) or ἀθίγγανοι (athinganoi, literally "untouchables"), a term applied to the sect of the Melchisedechians.[46][47][48] The Adsincani appear in an 11th-century text preserved in Mt Athos, The Life of Saint George the Athonite (written in the Georgian language), as "a Samaritan people, descendants of Simon the Magician, named Adsincani, who were renowned sorcerers and villains". In the text, emperor Constantine Monomachos employs the Adsincani to exterminate wild animals, who were destroying the game in the imperial park of Philopation.[49]

Bohémiens

Because many Romanies living in France had come via Bohemia, they were referred to as Bohémiens.[50] This term would later be adapted by the French to refer to a particular artistic and impoverished lifestyle of an individual, known as Bohemianism.

Other

- Hebrew: צוענים ʦoʿănim (from the city Soan in Egypt)

- Afrikaans: sigeuner after Dutch

- Armenian: գնչու gnčʿu

- Arabic: غجر ghájar

- Kurdish: قەرەچی qaraçı (from turkish), دۆم dom

- Basque: ijito,[51][52] buhame[53][54] (in the Northern Basque Country), erromintxela (for Basque-speaking Romanies)

- Georgian: ბოშები bošebi

- Persian: کولی Koli

- Japanese: ロマ Roma

- Chinese: 罗姆人 Luō mǔ rén

See also

- Didicoy

- Dom people

- List of Romani people

- Lom people

- Lyuli

- Origin of the Romani people

- Romani people by country

- Zott

References

- Definition at dictionary.cambridge.org

- Definition at Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English

- Definition at oxforddictionaries.com

- Definition at merriam-webster.com

- Definition at collinsdictionary.com

- Hancock, Ian F (2002). We Are the Romani People, Pg XXI. ISBN 978-1-902806-19-8. Retrieved 2008-07-31.

- p. 13 in Illona Klimova-Alexander's The Romani Voice in World Politics: The United Nations and Non-State Actors (2005, Burlington, VT.: Ashgate

- Rothéa, Xavier. "Les Roms, une nation sans territoire?" (in French). Retrieved 2008-07-31.

- p. 52 in Elena Marushiakova and Vesselin Popov's "Historical and ethnographic background; Gypsies, Roma, Sinti" in Will Guy [ed.] Between Past and Future: The Roma of Central and Eastern Europe [with a Foreword by Dr. Ian Hancock], 2001, UK: University of Hertfordshire Press

- Hancock, Ian F (2002). We Are the Romani People, Pg XX. ISBN 978-1-902806-19-8. Retrieved 2008-07-31.

- Hancock, Ian F (2002). We Are the Romani People, Pg XIX. ISBN 978-1-902806-19-8. Retrieved 2008-07-31.

- Nicolae, Valeriu; Slavik, Hannah (2007-07-01). Roma diplomacy, Pg 16. ISBN 978-1-932716-33-7. Retrieved 2008-07-31.

- Roma, Sinti, Gypsies, Travellers...The Correct Terminology about Roma Archived 2014-07-19 at the Wayback Machine at In Other WORDS project - Web Observatory & Review for Discrimination alerts & Stereotypes deconstruction

- The Institute for Middle East Understanding Archived 2007-05-23 at the Wayback Machine

- Online Etymology Dictionary - Douglas Harper

- McArthur, T. (ed.) The Oxford Companion to the English Language (1992) Oxford University Press ISBN 0-19-214183-X

- Monier-Williams, Sanskrit-English Dictionary (1899)

- From the Oxford English Dictionary (second edition, 1989; online version December 2011) Etymology section for the word gipsy:

From the quotations collected for the dictionary, the prevalent spelling of late years appears to have been gipsy. The plural gypsies is not uncommon, but the corresponding form in the singular seems to have been generally avoided, probably because of the awkward appearance of the repetition of y.

- Randall, Kay. "What's in a Name? Professor take on roles of Romani activist and spokesperson to improve plight of their ethnic group". Archived from the original on 2 May 2016. Retrieved 30 January 2013.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- Weyrauch, Walter Otto (2001). Gypsy law: Romani legal traditions and culture. University of California Press. p. 25. ISBN 978-0-520-22186-4.

- Bhopal, Kalwant; Myers, Martin (2008). Insiders, Outsiders and Others: Gypsies and Identity. Univ of Hertfordshire Press. p. 8. ISBN 978-1-902806-71-6. Retrieved 2010-05-20.

- Klímová-Alexander, Ilona (2005). The Romani voice in world politics: the United Nations and non-state actors. Non-state actors in international law. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 31. ISBN 978-0-7546-4173-5. Retrieved 2010-05-20.

- Tebbutt, Susan (1998). Sinti and Roma: Gypsies in German-Speaking Society and Literature. Oxford: Berghahn Books, Inc. p. x. ISBN 978-1571819215.

- Liégeois, Jean-Pierre (2007). Roma in Europe (3rd ed.). Strasbourg: Council of Europe Pub. p. 159. ISBN 978-9287160515.

- Totten, Samuel; Paul R. Bartrop; Steven Leonard (2008). Dictionary of genocide. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press. p. 371. ISBN 978-0313329678.

- Tom Dalzell, ed. (2007). The new Partridge dictionary of slang and unconventional English (Reprint. ed.). London [u.a.]: Routledge. p. 943. ISBN 978-0415259378.

- Merriam-Webster's pocket guide to English usage. Springfield, MA: Merriam-Webster. 1998. p. 178. ISBN 978-0877795148.

- Garner, Bryan A. (2009). Garner's modern American usage (3rd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. p. 405. ISBN 978-0195382754.

- H.E. Wedeck; Wade Baskin (1973). Dictionary of gypsy life and lore. New York: Philosophical Library. ISBN 978-0806529851.

- Garner, Bryan A. (2011). A dictionary of modern legal usage (3rd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. p. 400. ISBN 978-0195384208.

- Guido Bolaffi, ed. (2002). Dictionary of race, ethnicity and culture (1. publ., [Nachdr.]. ed.). London: Sage. p. 291. ISBN 978-0761969006.

- Oxford English Dictionary 2nd Edition 1989. "Gipsy, gypsy, n."

- Hancock, Ian (1995). A Handbook of Vlax Romani. Slavica Publishers. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-89357-258-7.

- "gitan" (in French). Dictionnaire de l'Académie française. Archived from the original on 2007-08-07. Retrieved 2007-08-26.

Emprunté de l'espagnol gitano, gitana, altération de Egiptano, proprement « Égyptien », car on attribuait aux bohémiens une origine égyptienne.

- Hancock, Ian F. (2002). We are the Romani people. Univ of Hertfordshire Press. p. xxi. ISBN 978-1-902806-19-8.

- "Hancock, Ian The 'Gypsy' stereotype and the sexualisation of Romani women". Archived from the original on 2011-07-17. Retrieved 2010-07-08.

- Matthews, John (6 October 1994). "9". The world atlas of divination: the systems, where they originate, how they work. Headline Book Publishing. p. 81. ISBN 978-0-7472-7928-0.

- Hancock, Ian. "PERSPECTIVES The Struggle for the Control of Identity". Roma Participation Program. pp. 1–8. Archived from the original on 2009-04-09. Retrieved 2009-05-11.

- Caravan Sites and Control of Development Act 1960 (c.62) The UK Statute Law Database.

- Ravi Low-Beer Challenging Gypsy planning policies occasional discussion paper number 1, Traveller Law Research Unit, Cardiff Law School, P O Box 427, Cardiff CF1 1XD. Retrieved 2008-10-09.

- Thomas Acton. Human Rights as a Perspective on Entitlements: The Debate over ‘Gypsy Fairs’ in England, Essex Human Rights Review Vol. 1 No. 1. July 2004, pp. 18-28, ISSN 1756-1957. See footnote 5 page 19 (page 2 of the PDF document).

- Traveller Law Research Unit, Cardiff University, (From March 1995 to December 2002). Retrieved 2008-10-09. Archived from original 2008

- Royal Galician Academy "xitano"

- Royal Galician Academy "cigano"

- Royal Galician Academy "cíngaro"

- White, Karin (1999). "Metal-workers, agriculturists, acrobats, military-people and fortune-tellers: Roma (Gypsies) in and around the Byzantine empire". Golden Horn. 7 (2). Archived from the original on 2014-09-20. Retrieved 2007-08-26.

- Bates, Karina. "A Brief History of the Rom". Archived from the original on 2010-06-15. Retrieved 2010-01-09.

- "Book Reviews" (PDF). Population Studies. 48 (2): 365–372. July 1994. doi:10.1080/0032472031000147856. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-09-14.

- P. Peeters, 'Histoire monastiques géorgiennes', Analecta Bollandiana, 36-37, 1917-19.

- Achim, Viorel (2004). The Roma in Romanian History. Budapest: Central European University Press. p. 11. ISBN 978-963-9241-84-8. OCLC 54529869.

- "ijito - Orotariko Euskal Hiztegia bilaketa". www.euskaltzaindia.eus.

- "ijito - Harluxet Hiztegi Entziklopedikoa". www1.euskadi.net.

- "buhame - Orotariko Euskal Hiztegia bilaketa". www.euskaltzaindia.eus.

- "buhame - Harluxet Hiztegi Entziklopedikoa". www1.euskadi.net.