Romani people in Bulgaria

Romani people (Bulgarian: цигани [tsiɡɐni], роми [rɔmi]) in Bulgaria constitute Europe's densest Romani minority. The Romani people in Bulgaria "speak Bulgarian, Turkish or Romani, depending on the region and their religious affiliations." [7]

цигани/роми в България Romane ando Bulgariya | |

|---|---|

| Total population | |

| 325,343 (2011 Census; 4.4%)[1]European Commission's average estimate: 750,000[2][3] (last updated 14 September 2010)[4] unofficial estimates: 800,000[5] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| nationwide, rural and urban | |

| Languages | |

| Religion | |

|

| Part of a series on |

| Romani people |

|---|

|

Diaspora

|

|

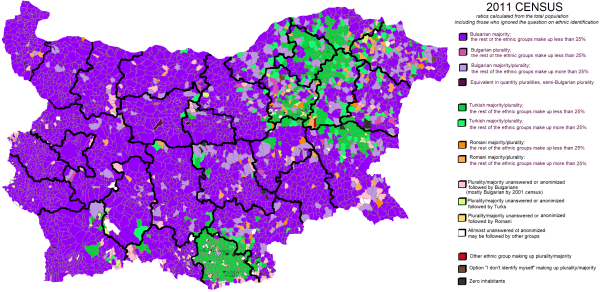

According to the latest census in 2011, the number of the Romani is 325,343, constituting 4.4% of the total population, in which only one ethnic group could be opted as an answer and 10% of the total population did not respond to the question on ethnic group.[1] In a conclusive report of the census sent to Eurostat, the authors of the census (the National Statistical Institute of Bulgaria) identified the census results on ethnicity as a "gross manipulation".[8] The former head of the National Statistical Institute of Bulgaria, Reneta Indzhova claims to have been fired by the Bulgarian Prime Minister in 2014 for attempting to check the actual number of the Romani and implied that neither the census did enumerate the Romani, nor its statistics did provide the "real data".[9] Unlike other censuses under Eurostat, which require the ethnic identification to be verified by a family tree, in the Bulgarian census the ethnic identification is completely up to the voluntarily identification of the enumerated and not up to any further investigation by the enumerators.[10]

The previous 2001 census recorded 370,908 Romani (4.7% of the population). The preceding 1992 census recorded 313,396 Romani (3.7% of the population), while a secret backstage 1992 census ordered by the Ministry of Interior recorded a figure of 550,000 Romani (6.5% of the population); the Ministry of Interior ordered at least two other secret censuses to enumerate the Romani in denial, the one in 1980 recorded 523,519 Romani, while the one in 1989 recorded that the number of the Romani was 576,927 (6.5% of the population) and that over half of the Romani identified as Turks.[11] The majority of the estimated 200,000-400,000 Muslim Romani tend to identify themselves as ethnic Turks,[12] some deny their origin, or identify as Bulgarians.

The demographic collapse in Bulgaria affects only ethnic groups other than the Romani.[13] According to data of the European Commission, to which Eurostat belongs, the Romani in Bulgaria number 750,000 and they constitute 10.33% of the population.[2][3] An NGO estimates that the number of the Romani in Bulgaria is twice as this high and their population grows by 35,000 a year.[14][15]

Overview

In Bulgaria, Romani are most commonly referred to as Tsigani (цигани, pronounced [tsiɡəni]), an exonym that some Romani resent and others embrace. The form of the endonym Roma in Bulgarian is romi (роми). They are generally younger, according to the 2011 census they make up 10.2% of the population aged up to 9 years, on a note 14.9% of the total age group being non-respondents.[16][17]

In Bulgaria Roma are discriminated: 59% to 80% of non-Roma have negative feelings towards Roma.[18] Roma constitute the majority of prison population according to self-identification of inmates, with 7000 prisoners (70%) out of 10,000 in total.[19] According to 2002 data, the poverty rate among Romani is 61.8%, in contrast to a rate of 5.6% among Bulgarians.[20] In 1997, 84% of Bulgarian Romani lived under the poverty line, compared with 32% of ethnic Bulgarians.[21] In 1994, the poverty rate of Romani was estimated at 71.4%, compared with 15% for Bulgarians.[22] The unemployment rate of non-Romani in Bulgaria was 25%, while of the Romani it was 65% in 2008, for instance in neighbouring Romania and Hungary the Romani had much lower unemployment rates - 14% and 21% respectively.[23][24] In 2016 only 23% of the Romani in Bulgaria are employed.[25] The unemployed enjoy more financial aid than other citizens, especially for children, which may have prompted the higher birth rates of the Romani.[26]

In 2011 the share of Romani with university degree reached 0.3%, while 6.9% have secondary education; the same share was 22.8%/47.6% for Bulgarians.[27]

The Turks are more negative towards the Romani than the Bulgarians, with 30-50% rejecting various interactions and friendship with Romani. Although only 25% of Romani parents object to their children to be married with a Bulgarian and a Turk, only 4% of the Bulgarians and 6% of the Turks would marry a Romani person.[28][29] Romani are avoided by the majority traditionally, especially for marriage, however, there are ethnically mixed people with Gypsy and Bulgarian parents who are called жоревци "zhorevtsi" (from the common name George).

Bulgaria participates in the Decade of Roma Inclusion, an international initiative to improve the socio-economic status and social inclusion of Roma, with eight other governments committing themselves to "work toward eliminating discrimination and closing the unacceptable gaps between Roma and the rest of society".[30] The rights of the Romani people in the country are also represented by political parties and cultural organizations, most notably the Civil Union "Roma". Noted Roma from Bulgaria include musicians Azis, Sofi Marinova and Ivo Papazov, surgeon Aleksandar Chirkov, politicians Toma Tomov and Tsvetelin Kanchev, footballer Marian Ognyanov, and 1988 Olympic boxing champion Ismail Mustafov.

History

Origin

The Romani people originate from Northern India,[31][32][33][34][35][36] presumably from the northwestern Indian states Rajasthan[35][36] and Punjab.[35]

The linguistic evidence has indisputably shown that roots of Romani language lie in India: the language has grammatical characteristics of Indian languages and shares with them a big part of the basic lexicon, for example, body parts or daily routines.[37]

More exactly, Romani shares the basic lexicon with Hindi and Punjabi. It shares many phonetic features with Marwari, while its grammar is closest to Bengali.[38]

Genetic findings in 2012 suggest the Romani originated in northwestern India and migrated as a group.[32][33][39] According to a genetic study in 2012, the ancestors of present Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes populations of northern India, traditionally referred to collectively as the Ḍoma, are the likely ancestral populations of the modern European Roma.[40]

In February 2016, during the International Roma Conference, the Indian Minister of External Affairs stated that the people of the Roma community were children of India. The conference ended with a recommendation to the Government of India to recognize the Roma community spread across 30 countries as a part of the Indian diaspora.[7]

Migration to Bulgaria

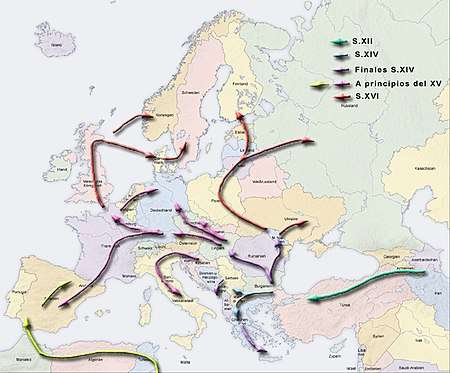

The Romani people emigrated from Northern India,[35][36] presumably from the northwestern Indian states of Rajasthan[35][36] and Punjab,[35] possibly as early as 600 A.D. They emigrated to the Middle East and then reached the European continent.[41] Moreover, "the Roma (the name is the plural form of the word "Rom") moved from India at the beginning of the 12th century, reached Europe in the 14th century and Central Europe in the 15th century."[42] The language of the Romani people is called Romani [romaňi čhib] or Romany. It is an Indic (or Indo-Aryan) language – like Sanskrit, Hindi, and Bengali — which belongs to the Indo-Iranian branch of the Indo-European family. The language retains much of the Indic morphology, phonology and lexicon, while its syntax has been heavily influenced by contact with other languages.

Bulgarian ethnologists Elena Marushiakova and Veselin Popov assert that no direct evidence indicates when precisely the Romani first appeared in Bulgaria. While they mention that other Bulgarian and international scholars have associated the 1387 Charter of Rila term Agoupovi Kleti with the Romani, they hold that the term refers to seasonal lodgings for mountain herdsmen. Instead, they delimit the mass settlement of Romani in Bulgarian territory between the 13th and 14th centuries, supporting this time frame with 13th- and 14th-century documents referring to Romani presence in the surrounding Balkan states.[43] According to Bulgarian sociologist Ilona Tomova, Ottoman fiscal reports between the 15th and 17th centuries indirectly indicate Romani settlement in Bulgaria since the 13th century, as most registered Romani possessed Slavonic names and were Christians.[44]

"Although the largest Roma migration wave to the Bulgarian lands seems to have occurred in the 13th and 14th centuries, many Roma arrived with the Ottoman troops, accompanying army craftsmen and complementary military units."

In addition, during the 14th and 15th centuries, Muslim Romani arrived in Bulgaria with the Ottoman rule, serving as auxiliaries, craftsmen, musicians and other professions.[44][45] Unlike the Ottoman Empire's other subjects in the millet system, Romani were governed based on their ethnicity, not their religious affiliation.[46] Ottoman tax records first mention Romani in the Nikopol region, where 3.5% of the registered households were Romani. Under Mehmed II's reign, all Romani – Christian and Muslim – paid a poll-tax that was otherwise imposed only on non-Muslims.[47]

During the 16th century, Suleiman I enacted laws to prohibit the mingling of Muslim and Christian Romani and to administer taxes collected from the Romani: the 1530 Gypsies in the Rumelia Region Act and a 1541 law for the Romani sancak.[44][48] Muslim Romani were taxed less than Christian Romani,[46] yet they were taxed more than other Muslims for not adhering to Islamic laws and customs.[49] Ottoman imperial assembly registers from 1558-1569 characterize the Romani as ehl-i fesad (people of malice), charging them with crimes such as prostitution, murder, theft, vagrancy and counterfeiting.[50]

Groups

Roma in Bulgaria are not a unified community in culture and lifestyle. The most widespread group of the Romani in the country are the yerlii or the 'local Roma', who are in turn divided into Bulgarian Gypsies (daskane roma) and Turkish Gypsies (horahane roma). The former are mostly Christian (Eastern Orthodox and Protestant), while the latter are Muslim. Many of the Muslim Romani or the so-called Turkish Gypsies are usually well integrated in the ethnic Turkish society in Bulgaria.[51] Many possess Turkish ethnic identity and speak Turkish in addition to Romani.[52][53][42] Moreover, between 50% and 75% of Romani are Muslims and more than 30 Romani dialects are reportedly used in the country. Muslim Romani can be divided into several linguistic groups: for example the Horahane Romani, who speak only Romani (although they know Turkish or Bulgarian) and identify themselves as Romani; Romani whose language is a mix between Romani and Turkish; Romani who use only Turkish (rarely Bulgarian and Romani); and Romani who can only speak Turkish, identifying themselves as either Romani or Turkish.[53][42]

A subgroup of the Bulgarian Gypsies in southern Bulgaria, the Asparuhovi bâlgari ("Asparuh Bulgarians") — that is known also as stari bâlgari ("Old Bulgarians"), sivi gâlâbi ("Grey Doves", "Grey Pigeons"), or demirdzhii — self-identify as the descendants of blacksmiths for Khan Asparuh's army.[54][55][56] Some deny any connection with the Romani and most do not speak Romani.[56]

Demographics

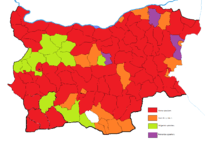

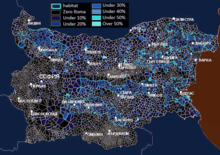

According to the 2011 census of the population of Bulgaria, there are 325,343 Gypsies in Bulgaria,[1] or 4.4 percent. 180,266 of these are urban residents and 145,077 rural.[57]

Most of the Roma, 66%, are young children and adults up to 29 years old, the same group constitutes 37% among ethnic Bulgarians, while 5% of Roma are 60 years and over, Bulgarians are 22%.[58]

From the 1992 census to the 2001 census, the number of Romani in the country has increased by 57,512, or 18.4%. The Romani were only 2.8% in 1910 and 2.0% in 1920.[59]

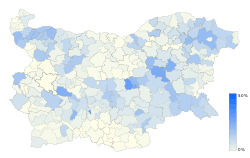

While the Romani are present in all provinces of Bulgaria, their highest percentages are in Montana Province (12.5%) and Sliven Province (12.3%) and their smallest percentage is in Smolyan Province, where they number 686[60] — about 0.05% of the population.

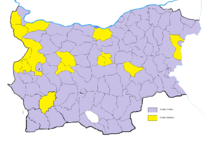

Varbitsa is possibly the only urban settlement where the Romani are the most numerous group. The largest Romani quarters are Stolipinovo in Plovdiv and Fakulteta in Sofia. The number of places where Romani constitute more than 50% of the population has doubled from the 1992 to the 2001 census. The largest village with a Romani majority is Gradets in Kotel Municipality.

| Province | Romani population (2011 census) | % |

|---|---|---|

| Blagoevgrad Province | 9,739 | 3.43% |

| Burgas Province | 18,424 | 4.97% |

| Dobrich Province | 15,323 | 8.81% |

| Gabrovo Province | 1,305 | 1.13% |

| Haskovo Province | 15,889 | 6.99% |

| Kardzhali Province | 1,296 | 0.99% |

| Kyustendil Province | 8,305 | 6.36% |

| Lovech Province | 5,705 | 4.38% |

| Montana Province | 18,228 | 12.71% |

| Pazardzhik Province | 20,350 | 8.27% |

| Pernik Province | 3,560 | 2.84% |

| Pleven Province | 9,961 | 4.15% |

| Plovdiv Province | 30,202 | 4.87% |

| Razgrad Province | 5,719 | 5.00% |

| Ruse Province | 8,615 | 3.98% |

| Shumen Province | 13,847 | 8.24% |

| Silistra Province | 5,697 | 5.11% |

| Sliven Province | 20,478 | 11.82% |

| Smolyan Province | 448 | 0.47% |

| Sofia City Province | 18,284 | 1.55% |

| Sofia Province | 17,079 | 7.40% |

| Stara Zagora Province | 24,018 | 7.80% |

| Targovishte Province | 7,767 | 7.27% |

| Varna Province | 13,432 | 3.16% |

| Veliko Tarnovo Province | 3,875 | 1.66% |

| Vidin Province | 7,282 | 7.66% |

| Vratsa Province | 10,082 | 6.18% |

| Yambol Province | 10,433 | 8.48% |

| Total[61] | 325,343 | 4.87%[62] |

Age structure

Although Roma constitute only 4.4 percent of the Bulgarian population, they constitute around 12 percent of all children aged between 0 and 9 years old according to the 2011 census.[63] In some municipalities, like Valchedram and Ruzhintsi in northwestern Bulgaria, more than the half of all children belong to the Roma ethnicity.[64]

| Roma population by age group and share of total Bulgarian population as of 2011 | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethnic group | Total | 0 – 9 | 10 – 19 | 20 – 29 | 30 – 39 | 40 – 49 | 50 – 59 | 60 – 69 | 70 – 79 | 80+ | ||||||||

| Roma | 325,343 | 67,568 | 59,511 | 59,442 | 49,572 | 37,723 | 28,411 | 15,833 | 6,031 | 1,252 | ||||||||

| Percentage of Bulgarian population | 4.9 | 12.0 | 9.7 | 6.8 | 5.1 | 4.1 | 3.0 | 1.8 | 1.0 | 0.4 | ||||||||

Problems of exclusion and discrimination

In a UNDP/ILO survey, Bulgarian Romani identified unemployment, economic hardship and discrimination in access to employment as major problems.

The Council of Europe body ECRI stated in its June 2003 third report on Bulgaria that Romani encounter "serious difficulties in many spheres of life", elaborating that:

"The main problems stem from the fact that the Roma districts are turning into ghettos. [...] Most Roma neighbourhoods consist of slums, precariously built without planning permission on land that often belongs to the municipalities [...]. As the Bulgarian authorities have not taken steps to address the situation, the people living in these districts have no access to basic public services, whether health care, public transport, waste collection or sanitation."[65]

To which the Bulgarian government answered officially in the same document:

ECRI has correctly observed that members of the Roma community encounter "serious difficulties" "in many spheres of life". The rest of this paragraph, however, regrettably contains sweeping, grossly inaccurate generalizations ... Due to various objective and subjective factors, many (but by no means all!) members of the Roma community found it particularly difficult to adapt to the new realities of the market economy. “…Romani mahala-dwellers are still captives of the past, holding onto and behaving according to preconceptions about the socialist welfare state that clash with the modern realities of a market economy and privatisation". (Skopje Report, p.6)[66]

More concretely, the allegation that the people living in these districts "have no access to basic public services" is largely inaccurate. Certain difficulties (though not remotely on the scale suggested) do exist in this regard, and the authorities are taking concrete measures to address them (see above). However, as the Advisor on Roma and Sinti issues at the OSCE, N. Gheorghe remarked during the Skopje meeting: “…many of the Roma confuse public services with rights to which they are entitled and which are guaranteed by the welfare state" (Skopje Report, p.16). ...

Concerning the issue of the electricity supply it should be noted that dwellers of such neighbourhoods sometimes refuse to pay their electricity bills. This attitude could at least in part be explained by the fact that “…Romani mahala-dwellers believe they have rights as citizens to electricity and other services, and that the state has an obligation to provide and to a large extent to subsidize them" (Skopje Report, p. 7). In these circumstances electricity suppliers may find themselves with no other option but to "sometimes cut off" the electricity supply in order to incite the consumers to commence honouring their debts. Such cut-offs are part of standard practice and the ethnic origin of the consumers is irrelevant in these cases.

With respect to welfare benefits, which allegedly "in some cases, moreover, Roma do not receive" while "they are entitled" to them, it should be underscored that Bulgaria’s social welfare legislation sets uniform objective criteria for access to welfare benefits for all citizens, irrespective of their ethnic origin (furthermore, any discrimination, including on ethnic grounds is expressly prohibited by law). The question of who is entitled or not entitled to welfare benefits is determined by the relevant services on the basis of a means test. Every single decision of these services must be (and is) in written form and clearly motivated. If a claimant is not satisfied with a decision, he/she is entitled to appeal it before the regional welfare office. Consequently, this allegation of ECRI is also erroneous."[65]

A monitoring report by the Open Society Institute found that Romani children and teenagers are less likely to enroll in primary and secondary schools than the majority population and less likely to complete their education if they do. Between 60% and 77% of Romani children enroll in primary education (ages 6–15), compared to 90-94% of ethnic Bulgarians. Only 6%-12% of Romani teenagers enroll in secondary education (ages 16–19). The drop-out rate is significant, but hard to measure, as many are formally enrolled but rarely attend classes.[67]

The report also indicates that Romani children and teenagers attend de facto segregated "Roma schools" in majority-Romani neighbourhoods and villages. These "Roma schools" offer inferior quality education; many are in bad physical condition and lack necessary facilities such as computers. As a result, Romani literacy rates, already below those for ethnic Bulgarians, are much lower still for Romani who have attended segregated schools.[68]

The official position of the Bulgarian government to such segregation is:

"There had never been a policy of "segregation" of Roma children in the national education system. The fact that in some neighbourhoods in certain towns particular schools were attended predominantly by pupils of Roma origin was an unintended consequence of the administrative division of the school system. According to the rules valid for all children irrespective of their ethnic origin, admittance to any public school was linked administratively to the domicile of the family. In neighbourhoods where the population was predominantly of Roma origin, this system produced schools, attended predominantly by pupils of Roma origin. It is precisely this situation that the authorities are taking special measures to rectify. Therefore, the word "segregation" with respect to Roma children is inaccurate."[65]

Romani children are often sent to special schools for children with intellectual disabilities or boarding schools for children with "deviant behavior" (so-called "delinquent schools"). According to reports of the Bulgarian Helsinki Committee (BHC), Romani made up half the number of students in schools for children with intellectual disabilities and about two-thirds of the students of the boarding schools, where the BHC found a variety of human rights abuses, including physical violence. In both sets of special schools, the quality of teaching is very poor and essential things such as desks, textbooks and teaching materials are inadequate or altogether lacking.[69]

On two occasions, the European Committee of Social Rights has found violations of the European Social Charter in situations with Bulgaria's Romani population: in 2006, concerning right to housing,[70] and in 2008, concerning right to health[71] — in both cases on complaints from the European Roma Rights Centre.

Political representation

According to a report of POLITEA, "For the most of the 1990s the only representation the Romani got was through the mainstream political parties. This was a very limited form of representation in which one or two Romani had a symbolic presence in Parliament during each term." The Bulgarian Constitution does not allow political parties based on ethnic, religious, or racist principles or ideology. However, "Twenty one Roma political organizations were founded between 1997 and 2003 in Bulgaria [...]".[72]

In the 2005 Bulgarian parliamentary election, three Romani parties took part: Euroroma, Movement for an Equal Public Model (as part of a coalition led by the Union of Democratic Forces) and the Civil Union "Roma" (as part of a coalition led by the Bulgarian Socialist Party).[73] Currently, the Movement for Rights and Freedoms represents[74] Muslim Romani. The party relies on the biggest share of Romani people, 44%[75] of the total Romani vote, including non-Muslims.

Romani people are considered second-class citizens by some Bulgarians.[76] Romani integration programmes funded by the European Union have had mixed success.[77]

Public opinion

The 2019 Pew Research poll found that 68% of Bulgarians held unfavorable views of Roma.[78]

See also

References

- "2011 POPULATION CENSUS – MAIN RESULTS" (PDF). Nsi.bg. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- "Roma integration in Bulgaria". European Commission - European Commission. 13 December 2016.

- "COMMUNICATION FROM THE COMMISSION TO THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT, THE COUNCIL, THE EUROPEAN ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL COMMITTEE AND THE COMMITTEE OF THE REGIONS". Brussels: EUROPEAN COMMISSION. April 2011. p. 15.

- "Roma and Travellers Team. TOOLS AND TEXTS OF REFERENCE. Estimates on Roma population in European countries"Council of Europe Roma and Travellers Division

- Silverman, Carol (2011). Romani Routes: Cultural Politics and Balkan Music in Diaspora. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199913350.

- "Национален съвет за сътрудничество по етническите и интеграционните въпроси". Nccedi.government.bg. Archived from the original on 13 January 2016. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- "Can Romas be part of Indian diaspora?". khaleejtimes.com. 29 February 2016. Retrieved 4 March 2016.

- Критичен доклад относно Преброяването на населението и жилищния фонд, проведено към 1 февруари 2011 година.

- "Бивш премиер без пенсия. Как живее Ренета Инджова?". БНТ (in Bulgarian).

- PhD, N.I.Todorov. "The Portal of Pleven, Bulgaria - Проф. Петър Иванов: Етнически деформации, нравствана деградация и демографски срив". www.plevenonline.com.

- Ilieva, Nadezhda (2012). NUMBER OF ROMA ETHNIC GROUP IN BULGARIA FROM THE LIBERATION TO THE BEGINNING OF THE 21ST CENTURY (BASED ON REGULAR CENSUSES) (Part 1) (PDF). Bulgarian Academy of Sciences. p. 75.

- "WikiLeaks: Islam and Islamic Extremism in Bulgaria - Novinite.com - Sofia News Agency". Novinite.com. 14 July 2011. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- Roberts, Lance W.; Ferguson, Barry; Bös, Mathias (1 February 2013). Multicultural Variations: Social Incorporation in Europe and North America. McGill-Queen's Press - MQUP. ISBN 9780773589056.

- "Академик д-р Петър Иванов: България се обезбългарява, топим се с 9 души на час". dir.bg.

- "Акад. Петър Иванов: Циганите у нас са 1,5 млн. души и главоломно се увеличават". Bulgarian Times (in Bulgarian). 16 August 2017.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 13 June 2012. Retrieved 13 June 2012.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Population by districts, municipalities, settlements and age as of 01.02.2011". Nsi.bg. Retrieved 24 August 2017.

- Carol Silverman (24 May 2012). Romani Routes: Cultural Politics and Balkan Music in Diaspora. p. 12. ISBN 9780195300949. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- "Само 10 000 в затвора, 7000 от тях са цигани". 24chasa.bg. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- Nations, United (2003). World Economic and Social Survey 2003: Trends and Policies in the World Economy - United Nations. ISBN 9789211091434. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- The Roma in Central and Eastern Europe: Avoiding the Dependency Trap, pp. 31, 39.

- Rebecca Jean Emigh; Iván Szelényi (2001). Poverty, Ethnicity, and Gender in Eastern Europe During the Market Transition. p. 47. ISBN 9780275968816. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- Revenga, Ana; Ringold, Dena; Tracy, William Martín (2002). Poverty and Ethnicity: A Cross-country Study of Roma Poverty in Central Europe. World Bank Publications. ISBN 9780821353394.

- Silverman, Carol (2011). Romani Routes: Cultural Politics and Balkan Music in Diaspora. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199913350.

- "EU agency study: Situation of Bulgarian Roma is appalling". The Sofia Globe. 29 November 2016.

- https://china-cee.eu/2019/05/09/bulgaria-social-briefing-bulgarian-governmental-party-issued-a-new-concept-for-the-integration-of-the-unsocialised-gypsy-roma-ethnicity/

- Salverda, Wiemer; Checchi, Daniele; Marx, Ive; McKnight, Abigail (2014). Changing Inequalities and Societal Impacts in Rich Countries. ISBN 9780199687428.

- "Gallup".

- "Две трети от българите приемат етническото разделение за нормално - Mediapool.bg". Mediapool.bg.

- "Declaration of the Decade of Roma Inclusion 2005-2015". Decade of Roma Inclusion 2005-2015. 2005. Retrieved 20 April 2007.

- Hancock 2002, p. xx: 'While a nine century removal from India has diluted Indian biological connection to the extent that for some Romani groups, it may be hardly representative today, Sarren (1976:72) concluded that we still remain together, genetically, Asian rather than European'

- Mendizabal, Isabel (6 December 2012). "Reconstructing the Population History of European Romani from Genome-wide Data". Current Biology. 22 (24): 2342–2349. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2012.10.039. PMID 23219723.

- Sindya N. Bhanoo (11 December 2012). "Genomic Study Traces Roma to Northern India". The New York Times.

- Current Biology.

- K. Meira Goldberg; Ninotchka Devorah Bennahum; Michelle Heffner Hayes (6 October 2015). Flamenco on the Global Stage: Historical, Critical and Theoretical Perspectives. p. 50. ISBN 9780786494705. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- Simon Broughton; Mark Ellingham; Richard Trillo (1999). World Music: Africa, Europe and the Middle East. p. 147. ISBN 9781858286358. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- Šebková, Hana; Žlnayová, Edita (1998), Nástin mluvnice slovenské romštiny (pro pedagogické účely) (PDF), Ústí nad Labem: Pedagogická fakulta Univerzity J. E. Purkyně v Ústí nad Labem, p. 4, ISBN 978-80-7044-205-0, archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016

- Hübschmannová, Milena (1995). "Romaňi čhib – romština: Několik základních informací o romském jazyku". Bulletin Muzea Romské Kultury. Brno (4/1995).

Zatímco romská lexika je bližší hindštině, marvárštině, pandžábštině atd., v gramatické sféře nacházíme mnoho shod s východoindickým jazykem, s bengálštinou.

- "5 Intriguing Facts About the Roma". Live Science.

- Rai, N; Chaubey, G; Tamang, R; Pathak, AK; Singh, VK (2012), "The Phylogeography of Y-Chromosome Haplogroup H1a1a-M82 Reveals the Likely Indian Origin of the European Romani Populations", PLOS One, 7 (11): e48477, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0048477, PMC 3509117, PMID 23209554

- Leslie Strnadel; Patrick Erdley (2012). Bulgaria (Other Places Travel Guide). Books.google.ca. p. 189. ISBN 9780982261996. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- "Bulgaria : Introduction : 1/37" (PDF). Ec.europa.eu. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- Marushiakova et al., Gypsies in the Ottoman Empire: a contribution to the history of the Balkans, p. 19

- Tomova, Ethnic Dimensions of poverty in Bulgaria, p. 15

- Marushiakova et al., Gypsies in the Ottoman Empire: a contribution to the history of the Balkans, p. 26

- Celik, Exploring Marginality in the Ottoman Empire: Gypsies or People of Malice (Ehl-i Fesad) as Viewed by the Ottomans Authors, p. 5

- Marushiakova et al., Gypsies in the Ottoman Empire: a contribution to the history of the Balkans, p. 27

- Marushiakova et al. “A History of the Roma in Bulgaria”. Patrin Web Journal. Retrieved on 2009-03-01.

- Barany, The East European gypsies: regime change, marginality, and ethnopolitics, p. 85

- Celik, Exploring Marginality in the Ottoman Empire: Gypsies or People of Malice (Ehl-i Fesad) as Viewed by the Ottomans Authors, p. 20

- https://journals.openedition.org/balkanologie/323

- "Discrimination Against Roma Muslims of Europe". YouTube. 4 March 2010. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- "Education and Training". Archived from the original on 21 February 2012. Retrieved 13 November 2012.

- Slavkova, Magdalena (December 2008). "'Being Gypsy in Europe. The Case of Bulgarian Roma Workers in Spain', Balkanologie". Balkanologie. Revue d'Études Pluridisciplinaires. X, № 1–2 (Vol. XI, n° 1–2). Retrieved 24 February 2009.

- Marushiakova, E., Popov, V. (2000). Acton, T. (ed.). 'Myth as Process', Scholarship and the Gypsy Struggle. Commitment in Romani Studies (PDF). Hatfield: University of Hertfordshire Press. p. 90.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Pamporov, Alexei (2006). Ромското всекидневие в България (Romani Daily Life in Bulgaria) (PDF) (in Bulgarian). Sofia: Международен център за изследване на малцинствата и културните взаимодействия. pp. 23–4, 62–3. ISBN 978-954-8872-63-8. Retrieved 24 February 2009.

- "Census Results 2011". Censusresults.nsi.bg. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- Jenny Engström (2009). Democratisation and the Prevention of Violent Conflict: Lessons Learned from ... p. 77. ISBN 9780754674344. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- "Assoc. Prof. Dr. Kiril Kertikov, Europeisation or "tsiganisation" of Bulgaria. Institute of Sociology, Bulgarian Academy of Sciences" (in Bulgarian). In: Balkans'21, vol. 1, 2002, ISSN 1311-9583. Retrieved 3 August 2007.

- "ПРЕБРОЯВАНЕ 2011" (in Bulgarian). National Statistical Institute. 2011. Retrieved 18 June 2006.

- WebDesign Ltd. www.webdesign-bg.eu. "Population". Nsi.bg. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- The 2011 percentage of the ethnic groups is calculated only from those who answered the optional question on ethnicity (6,680,980 in total) and does not include around 700,000 people who did not answer the question.

- "Format ref". censusresults.nsi.bg.

- "Data". strategy.bg.

- "Third report on Bulgaria" (PDF). Council of Europe - ECRI. 2003. Retrieved 22 February 2009.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 July 2007. Retrieved 20 September 2007.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Equal access to quality education for Roma, Bulgaria" (PDF). Open Society Institute - EU Monitoring and Advocacy Program (EUMAP). 2007. pp. 32–34. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 February 2009. Retrieved 20 April 2007.

- Equal access to quality education for Roma, Bulgaria, pp. 18-20.

- Bulgarian Helsinki Committee (2002). Помощните училища в България (Remedial Schools in Bulgaria). ISBN 978-954-9738-14-8.Bulgarian Helsinki Committee (2001). Социално-педагогически и възпитателни училища-интернати (Social-Pedagogical Boarding Schools and Correctional Boarding Schools). pp. 391–392. ISBN 978-954-9738-03-2.Bulgarian Helsinki Committee (2005). В името на институцията: поправителните училища в България (In the Name of the Institution: Schools for Delinquent Children in Bulgaria). ISBN 978-954-9738-21-6.

- "La Charte sociale européenne" (PDF). Coe.int. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- "La Charte sociale européenne" (PDF). Coe.int. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- "The Political Representation of the Roma Minority in Bulgaria: (1990-2005)". POLITEIA - Participation for Citizenship and Democracy in Europe. 2005. Archived from the original on 20 April 2012. Retrieved 20 July 2007.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 10 May 2011. Retrieved 18 January 2011.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Selected Muslim Historical Sites and Monuments in Bulgaria". surface.syr.edu. Syracuse University Surface.

- "Проучване на Алфа Рисърч: 44% от ромите са подкрепили ДПС". Trud.bg. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- Library of Congress 2006, p. 6.

- "Bulgarian Roma snub new EU plan for gypsy integration". EUbusiness. 21 June 2011. Retrieved 21 June 2012.

- "European Public Opinion Three Decades After the Fall of Communism – 6. Minority groups". Pew Research Center. 14 October 2019.

Sources

- Giordano, Christian; Andrea Boscoboinik, Dobrinka Kostova, Milena Benovska-Sabkova, Annabel Chanteraud (2003). Roma's Identities in Southeast Europe: Bulgaria (PDF). Rome: Ethnobarometer. ISBN 978-88-88235-03-5.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Marushiakova, Elena; Veselin Popov (2001). Gypsies in the Ottoman Empire: a contribution to the history of the Balkans. Univ of Hertfordshire Press. ISBN 978-1-902806-02-0.

- Marushiakova, Elena; Popov, Vesselin (1997). Gypsies (Roma) in Bulgaria. Peter Lang Verlag. ISBN 978-0820432168.

- Slavkova, Magdalena; Yeris Erolova (2005). "Study of the educational adjustment of the Roma population of Nova Zagora municipality" (in Bulgarian). IMIR.

- Tomova, Ilona (1998). "This report is one of the studies commissioned for the social assessment of Bulgaria by the Social Development Team Europe and Central Asia Region" (PDF). The World Bank: 63. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)

External links

- The 2011 census of the population of the Republic of Bulgaria

- The largest archive of gypsy music on the Internet - 100,000 gypsy songs

- Studii Romani Specialized Library with Archive

- CEGA (СЕГА) Foundation

- Bulgarian Subject Files - Social Issues: Minorities: Gypsys Open Society Archives, Budapest

- Bulgarian Roma Grassroot NGO Roma Together