Bahram V

Bahram V (Middle Persian: 𐭥𐭫𐭧𐭫𐭠𐭭 Wahrām), also known as Bahram Gor (Persian: بهرام گور, "Bahram the onager") was the fifteenth king (shah) of the Sasanian Empire, ruling from 420 to 438.

| Bahram V 𐭥𐭫𐭧𐭫𐭠𐭭 | |

|---|---|

| King of Kings of Iran and Aniran | |

5th-century plate with a hunting scene from the tale of Bahram V and Azadeh. | |

| Shahanshah of the Sasanian Empire | |

| Reign | 420–438 |

| Predecessor | Khosrow the Usurper |

| Successor | Yazdegerd II |

| Born | 400 |

| Died | 438 (aged 38) Media |

| Consort | Sapinud |

| Issue | Yazdegerd II |

| House | House of Sasan |

| Father | Yazdegerd I |

| Mother | Shushandukht |

| Religion | Zoroastrianism |

The son of Yazdegerd I, Bahram was exiled at an early age to the Lahkmid court in al-Hira, where he was raised under the tutelage of the Lakhmid kings. After the assassination of Yazdegerd I, Bahram hurried to the Sasanian capital of Ctesiphon with a Lakhmid army, and won the favour of the nobles and priests, according to a long-existing popular legend, after withstanding a trial against two lions.

Bahram V's reign was generally peaceful, with two brief wars—first against his western neighbours, the Eastern Roman Empire, and then against his eastern neighbours, the Hephthalites, who were disturbing the Sasanian eastern provinces. It was also during his reign that the Arsacid line of Armenia was replaced by a marzban (governor of a frontier province, "margrave"), which marked the start of a new era in Armenia, known in Armenian historiography as the "Marzpanate period".

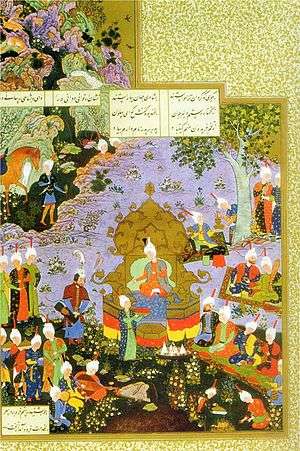

Bahram V is a central figure in several of the most famous works in Persian literature. He is mentioned in Ferdowsi's Shahnameh ("Book of Kings") written between 977 and 1010, and he is the protagonist of Nizami Ganjavi's romantic epic Haft Peykar (also known as the "Bahramnameh"), written in 1197. The Seven Beauties were princesses, which—in Nizami's imagination—became Bahram's wives and received each their own residence in his palace. He visited them on a rotating basis, and they entertained him with exciting stories. He is also the focal point in the Hasht-Bihisht ("Eight Paradises"), written by Amir Khusrow in ca. 1302.

Bahram V is remembered as one of the most famous kings in Iranian history, due to his cancellation of taxes and public debt at celebratory events, his encouragement of musicians, and his enjoyment of hunting. However, albeit he is revered in many historical tales as a bold, vivid, and suited ruler, his reign may be considered the start of the decline of the Sasanian Empire, which lasted until the reign of Kavad I (r. 488–496 and 498–531), when the empire experienced a resurgence.

Name

His theophoric name "Bahram" is the New Persian form of the Middle Persian Warahrān (also spelled Wahrām), which is derived from the Old Iranian Vṛθragna. The Avestan equivalent was Vərəθraγna, the name of the god of victory, whilst the Parthian version was *Warθagn. The name is transliterated in Greek as Baranes.[1]

Early life and rise to power

Bahram V was born around 400.[2] He was the son of shah Yazdegerd I (r. 399–420) and Shushandukht, a daughter of the Jewish exilarch. Richard Frye believes that Yazdagird's marriage to a daughter of the patriarch of the Jews is "probably folk tales".[3] Bahram, during his youth, fell out with his father due to a disagreement, which made the latter send him to exile in the Lakhmid court in al-Hira, where he was raised under the tutelage of the Lakhmid king al-Nu'man I ibn Imru' al-Qays (r. 390–418).[4] There al-Nu'man provided Bahram with teachers from the Sasanian court, where Bahram was taught law, archery, and equestrian arts.[5]

Since the death of the powerful Sasanian shah Shapur II (r. 309–379), the aristocrats and priests had expanded their influence and authority at the cost of the Sasanian government, nominating, dethroning, and murdering shahs, which included Yazdegerd I, who was murdered on 21 January 420. They now sought to stop the sons of Yazdegerd I from ascending the throne—Shapur IV, who was the eldest son of Yazdegerd I and governor of Armenia, quickly rushed to the Sasanian capital of Ctesiphon, and ascended the throne. He was, however, shortly after, murdered by the nobles and priests, who elected a son of Bahram IV, Khosrow, as shah.[4]

Bahram was informed about the news of Yazdegerd I's death when he was in the Arabian Desert—he opposed the decision of the nobles, and asked al-Mundhir I ibn al-Nu'man (who had succeeded his father al-Nu'man I) for military assistance, who agreed to help him.[6] Bahram and al-Mundhir I, at the head of an army of numerous soldiers, marched towards Ctesiphon, where Bahram promised that he would not reign like his father Yazdegerd I did. According to a long-existing popular legend written in the Shahnameh ("The Book of Kings"), Bahram suggested that the royal crown and attire should be placed between two lions, and the person who retrieved them by killing the wild animals should be recognized as the shah of Iran.

Khosrow chose to pull out, whilst Bahram withstood the trial and won the throne.[4] Bahram distrusted the nobles, who had been unreliable to the earlier Sasanian shahs, and thus chose instead to seek support from the Zoroastrian priesthood. He was the first Sasanian shah to not be crowned by a noble, but by a chief priest (mowbed).[7]

Reign

War with Rome

At the urging of the Zoroastrian priests, Bahram V began his reign with a systematic persecution of the Christians as reprisal for attacks against Zoroastrian temples by Christians during his reign; Bahram continued this persecution, during which many died. Among them there was James Intercisus, a political counsellor of Yazdegerd I's, who had converted to Zoroastrianism but then converted back to Christianity.[8]

The persecuted Christians fled to Roman territory, and were welcomed by the bishop of Constantinople, Atticus, who informed the Emperor of the persecution. The Eastern Roman Emperor Theodosius II was at the time deeply influenced by his religious sister Pulcheria, and had become more and more interested in Christianity.[8] The Roman-Sasanian relationship already had some friction. The Sasanians had hired some Roman gold-diggers, but now refused to send them back; furthermore, the Sasanians seized the properties of Roman merchants. So, when Sasanian ambassadors reached the Roman court to ask for the fugitives, Theodosius chose to break the peace and declare war, rather than giving them back.[8]

In the year 421, the Romans sent their general Ardaburius with an extensive contingent into Armenia. Ardaburius defeated the Sasanian commander Narseh and proceeded to plunder the province of Arzanene and lay siege to Nisibis. Ardaburius abandoned the siege in the face of an advancing army under Bahram, who in turn besieged Theodosiopolis (probably Theodosiopolis in Osroene).[8]

The peace treaty that ended the war (422) was negotiated by the magister officiorum Helio. It returned everything to the situation before the war (status quo ante bellum). Both parts agreed to reject Arab defectors of the other part,[9] as well as to guarantee liberty of religion in their territories.[10]

War with the Hephthalites

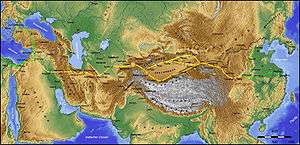

While Bahram was occupied with the war with the Romans, the rich city of Marv was captured by the Hephthalites. Bahram was thus forced to pay tribute to the Hephthalites, in order to stop their incursions into his empire. When Bahram had made peace with the Romans, he started preparing to deal with the Hephthalites. Not only was Marv a rich city, but also an important trading spot on the Silk Road, which passed through Central Asia and continued through Iran to Europe.

Bahram shortly invaded the domains of the Hephthalites, and recaptured Marv, killing the Hephthalite ruler, and seizing many riches. He then erected a pillar at the Amu Darya, which marked that the river constituted his empire's eastern frontier. By 427, he had fully secured his eastern section of the empire, and the inhabitants of Bukhara had started minting coins which imitated the coins of Bahram V, which implies that he had either conquered the city, or had left a strong influence there.[11]

To further strengthen Sasanian supremacy in Central Asia, Bahram appointed his brother, Narseh, as the governor of the eastern provinces, with his capital at Balkh.[12] Furthermore, in order to demonstrate his appreciation to Ahura Mazda, Bahram bestowed most of his booty to the Adur Gushnasp, one of the three holy temples of Iran.[12]

Relations with Armenia

The situation in Armenia occupied Bahram immediately after the conclusion of peace with Rome. Armenia had been without a king since Bahram's brother Shapur IV had vacated the country in 418. Bahram now desired that a descendant of the royal line of kings, a scion of the Arsacids, should be on the throne of Armenia. With this intention in mind, he selected an Arsacid named Artaxias IV (Artashir IV), a son of Vramshapuh, and made him king of Armenia.[13]

But the newly appointed king did not have a good character. The frustrated nobles petitioned Bahram to remove Artaxias IV and admit Armenia into the Sasanian Empire so that the province would be under the direct control of the Sasanian Empire.[14] However, the annexation of Armenia by Iran was strongly opposed by the Armenian patriarch Isaac of Armenia, who felt that the rule of a Christian was better than that of a non-Christian regardless of his character or ability. Despite his strong protests, however, Armenia was annexed by Bahram, who placed it under the charge of a Sasanian governor in 428.[15]

Death and legacy

According to a popular legend, Bahram died in 438 while hunting in Media.[16] He was succeeded by his son Yazdegerd II. Bahram V has left behind a rich and colorful legacy, with numerous legends and fantastical tales. His fame has survived the decline of Zoroastrianism and the anti-Iranian measures of the Umayyads and the Mongols, and many of the stories have been incorporated into contemporary Islamic lore.

His legacy even survives outside Iran. He is the king who receives the Three Princes of Serendip in the tale that gave rise to the word Serendipity. He is believed to be the inspiration for the legend of Bahramgur prevalent in the Punjab.

He is a great favourite in Iranian tradition, which relates many stories of his valour and beauty; of his victories over the Romans, Hephthalites, Indians, and Africans; and of his adventures in hunting and in love. He is called Bahram Gur, meaning Onager, "on account of his strength and courage".[17][18] Another interpretation is that he was a hunter of onagers.[18]

For example, the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam, translated by Edward FitzGerald, quatrain 17:

"They say the Lion and the Lizard keep

The Courts where Jamshyd gloried and drank deep:

And Bahram, that great Hunter - the Wild Ass

Stamps o'er his Head, and he lies fast asleep."

To which Fitzgerald adds the following footnote (1st edition, 1859): "Bahram Gur - Bahram of the Wild Ass from his fame in hunting it - a Sasanian sovereign, had also his seven palaces, each of a different colour; each with a Royal mistress within; each of whom recounts to Bahram a romance. The ruins of three of these towers are yet shown by the peasantry; as also the swamp in which Bahram sunk while pursuing his Gur.

Some have judged Bahram V to have been rather a weak monarch, after the heart of the grandees and the priests. He is said to have built many great fire-temples, with large gardens and villages (Tabari).[17]

Coins

The coins of Bahram V are chiefly remarkable for their crude and coarse workmanship and for the number of the mints from which they were issued. The mint-marks include Ctesiphon, Hamadan, Spahan, Arbela, Ledan, Nahavand, Asoristan, Khuzistan, Media, and Kirman. The headdress has the mural crown in front and behind, but interposes between these two detached fragments a crescent and a circle, emblems, no doubt, of the sun and moon gods. The reverse shows the usual fire-altar, with guards, or attendants, watching it. The king's head appears in the flame upon the altar.

The Seven Beauties

The Seven Beauties (Persian: هفت پیکر) also known as Bahramnameh (بهرامنامه, The Book of Bahram) is a famous romantic epic written in 1197 by the Persian poet Nizami Ganjavi. A pre-Islamic story of Persian origin, it was dedicated to the ruler of Maragha, 'Ala' Al-Din korp Arslan. It is a romanticized biography of Bahram, who is born to Yazdegerd I after twenty years of childlessness and supplication to Ahura Mazda for a child.[19] His adventurous life had already been treated by Ferdowsi in the Shahnameh, to which fact Nizami alludes a number of times.[20] In general, his method is to omit those episodes that the earlier poet had treated, or to touch on them only very briefly, and to concentrate on new material.[19] The poet starts by giving an account of the birth of Bahram and his upbringing in the court of the Arab king al-Nu'man and his fabled palace Khwarnaq. Bahram, whose upbringing is entrusted to al-Nu'man, becomes a formidable huntsman.

While wandering through the fabled palace, he discovers a locked room which contains a depiction of seven princesses; hence the name Haft Paykar (seven beauties). Each of these princesses is from the seven different climes (the traditional Zoroastrian division of the Earth) and he falls in love with them. His father Yazdegerd I passes away and Bahram returns to Iran to claim his throne from pretenders. After some episodes he is recognized as shah and rescues the Iranians from a famine. Once the country is stable, the shah searches for the seven princesses and wins them as his brides. His architect is ordered to construct seven domes for each of his new brides.

The architect tells him that each of the seven climes is ruled by one of the seven planets (the classical planetary system of the Zoroastrian world) and advises him to assure good fortune by adorning each dome with the color that is associated with each clime and planet. Bahram is skeptical but follows the advice of the architect. The princesses take up residence in the splendid pavilions. On each visit, the shah visits the princesses on successive days of the week; on Saturday the Indian princess, who is governed by Saturn and so on. The princesses names are Furak (Nurak), the daughter of the Rajah of India, as beautiful as the moon; Yaghma Naz, the daughter of the Khaqan of the Turks; Naz Pari, the daughter of the king of Khwarazm; Nasrin Nush, the daughter of the king of the Slavs; Azarbin (Azareyon), the daughter of the king of Morocco; Humay, the daughter of the Roman Caesar; and Diroste (wholesome), a beautiful Iranian princess from the House of Kay Kāvus.

Each princess relates to the shah a story matching the mood of her respective color.[19] These seven beautifully constructed, highly sensuous stories occupy about half of the whole poem.[19] While the shah is busy with the seven brides, his evil minister seizes power in the realm. Bahram discovers that the affairs of Iran are in disarray, the treasury is empty and the neighboring rulers are posed to invade. He clears his mind first by going hunting. After returning from the hunt, he sees a suspended dog from a tree. The owner of the dog, who was a shepherd, tells the story of how his faithful watchdog had betrayed his flock to a she-wolf in return for sexual favors.[19] He starts investigating the corrupt minister and from the multitude of complaints, he selects seven who tell him the injustice they have suffered. The minister is subsequently put to death and Bahram restores justice and orders the seven pleasure-domes to be converted to fire temples[19] for the pleasure of God. Bahram then goes hunting for the last time but mysteriously disappears. As a pun on words, while trying to hunt the wild ass (gūr) he instead finds his tomb (gūr).[19]

References

- Wiesehöfer 2018, pp. 193-194.

- Bosworth 1999, p. 82.

- Frye 1984, p. 319.

- Klíma 1988, pp. 514-522.

- Bosworth 1999, p. 84.

- Bosworth 1999, p. 87.

- Traina 2009, p. 121.

- Dodgeon, Greatrex & Lieu 2002b, pp. 36-43.

- Malchus, fragment 1.4-7.

- Chr. Arb., 16.

- Frye 1984, p. 352.

- Kia 2016, p. 238.

- A Fifth Century Hoard of Sasanian Drachms (A.D. 399-460), Hodge Mehdi Malek, Iran, Vol. 33, (1995), British Institute of Persian Studies, 68.

- Introduction to Christian Caucasian History:II: States and Dynasties of the Formative Period, Cyril Toumanoff, Traditio, Vol. 17, 1961, Fordham University, 6.

- Simon Payaslian, The History of Armenia:From the Origins to the Present, (Palgrave Macmillan, 2007), 40.

- Daryaee 2009, p. 23.

-

- Bosworth 1999, p. 81.

- "HAFT PEYKAR – Encyclopaedia Iranica". Iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 2014-03-23.

- Meisami, Julie Scott (1995). The Haft Paykar: A Medieval Persian Romance. Oxford University Press.

Abû Muhammad Ilyas ibn Yusuf ibn Zaki Mu'ayyad, known by his pen-name of Nizami, was born around 1141 in Ganja, the capital of Arran in Transcaucasian Azerbaijan, where he remained until his death in about 1209. His father, who had migrated to Ganja from Qom in north central Iran, may have been a civil servant; his mother was a daughter of a Kurdish chieftain; having lost both parents early in his life, Nizami was brought up by an uncle. He was married three times, and in his poems laments the death of each of his wives, as well as proferring advice to his son Muhammad. He lived in an age of both political instability and intense intellectual activity, which his poems reflect; but little is known about his life, his relations with his patrons, or the precise dates of his works, as the accounts of later biographers are colored by the many legends built up around the poet

Sources

- Bosworth, C.E., ed. (1999). The History of al-Ṭabarī, Volume V: The Sāsānids, the Byzantines, the Lakhmids, and Yemen. SUNY Series in Near Eastern Studies. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-4355-2.

- Shahîd, Irfan (1986). "Lakhmids". In Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E.; Lewis, B. & Pellat, Ch. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume V: Khe–Mahi. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 632–634. ISBN 90-04-07819-3.

- Traina, Giusto, 428 AD, An Ordinary Year at the End of the Roman Empire, Princeton University Press, 2009. ISBN 978-0-691-15025-3

- Pourshariati, Parvaneh (2008), Decline and Fall of the Sasanian Empire: The Sasanian-Parthian Confederacy and the Arab Conquest of Iran, London and New York: I.B. Tauris, ISBN 978-1-84511-645-3

- Daryaee, Touraj (2009). Sasanian Persia: The Rise and Fall of an Empire. I.B.Tauris. pp. 1–240. ISBN 0857716662.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Frye, Richard Nelson (1984). The History of Ancient Iran. C.H.Beck. pp. 1-411. ISBN 9783406093975.

The history of ancient iran.

CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Kia, Mehrdad (2016). The Persian Empire: A Historical Encyclopedia [2 volumes]: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1610693912.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Klíma, O. (1988). "Bahrām V Gōr". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. III, Fasc. 5. London et al. pp. 514–522.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wiesehöfer, Josef (2018). "Bahram I". In Nicholson, Oliver (ed.). The Oxford Dictionary of Late Antiquity. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-866277-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bahram V. |

- Encyclopedia Iranica, "Bahrām V Gōr ", O. Klíma

- Encyclopedia Iranica, "Bahrām V Gōr in Persian Legend and Literature", W. L. Hanaway, Jr

- The Civilizations of the Ancient Near East by George Rawlinson

- Tales of the Punjab by Flora Annie Steel

- Persian Literature in Translation The ackard Humanities Institute: Haft Paikar: TRANSLATED FROM THE PERSIAN,WITH A COMMENTARY, BY C. E. WILSON, B.A. (LOND.)- Romanticized story about Bahram Gur

Bahram V | ||

| Preceded by Khosrow the Usurper |

King of kings of Iran and Aniran 420–438 |

Succeeded by Yazdegerd II |

.png)