Red-tailed hawk

The red-tailed hawk (Buteo jamaicensis) is a bird of prey that breeds throughout most of North America, from the interior of Alaska and northern Canada to as far south as Panama and the West Indies. It is one of the most common members within the genus of Buteo in North America or worldwide.[2] The red-tailed hawk is one of three species colloquially known in the United States as the "chickenhawk", though it rarely preys on standard-sized chickens.[3] The bird is sometimes also referred to as the red-tail for short, when the meaning is clear in context. Red-tailed hawks can acclimate to all the biomes within their range, occurring on the edges of non-ideal habitats such as dense forests and sandy deserts.[4] The red-tailed hawk occupies a wide range of habitats and altitudes including deserts, grasslands, coniferous and deciduous forests, agricultural fields and urban areas. Its latitudinal limits fall around the tree line in the Arctic and the species is absent from the high Arctic. It is legally protected in Canada, Mexico, and the United States by the Migratory Bird Treaty Act.

| Red-tailed hawk | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Accipitriformes |

| Family: | Accipitridae |

| Genus: | Buteo |

| Species: | B. jamaicensis |

| Binomial name | |

| Buteo jamaicensis (Gmelin, 1788) | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

|

Buteo borealis | |

The 14 recognized subspecies vary in appearance and range, varying most often in color, and in the west of North America, red-tails are particularly often strongly polymorphic, with individuals ranging from almost white to nearly all black.[5] The subspecies Harlan's hawk (B. j. harlani) is sometimes considered a separate species (B. harlani).[6] The red-tailed hawk is one of the largest members of the genus Buteo, typically weighing from 690 to 1,600 g (1.5 to 3.5 lb) and measuring 45–65 cm (18–26 in) in length, with a wingspan from 110–141 cm (3 ft 7 in–4 ft 8 in). This species displays sexual dimorphism in size, with females averaging about 25% heavier than males.[2][7]

The diet of red-tailed hawks is highly variable and reflects their status as opportunistic generalists, but in North America, it is most often a predator of small mammals such as rodents. Prey that is terrestrial and diurnal is preferred so types such as ground squirrels are preferential where they naturally occur.[8] Large numbers of birds and reptiles can occur in the diet in several areas and can even be the primary foods. Meanwhile, amphibians, fish and invertebrates can seem rare in the hawk’s regular diet; however, they are not infrequently taken by immature hawks. Red-tailed hawks may survive on islands absent of native mammals on diets variously including invertebrates such as crabs, or lizards and birds. Like many Buteo, they hunt from a perch most often but can vary their hunting techniques where prey and habitat demand it.[5][9] Because they are so common and easily trained as capable hunters, the majority of hawks captured for falconry in the United States are red-tails. Falconers are permitted to take only passage hawks (which have left the nest, are on their own, but are less than a year old) so as to not affect the breeding population. Adults, which may be breeding or rearing chicks, may not be taken for falconry purposes and it is illegal to do so. Passage red-tailed hawks are also preferred by falconers because these younger birds have not yet developed the adult behaviors which would make them more difficult to train.[10]

Description

Red-tailed hawk plumage can be variable, depending on the subspecies and the region. These color variations are morphs, and are not related to molting. The western North American population, B. j. calurus, is the most variable subspecies and has three main color morphs: light, dark, and intermediate or rufous. The dark and intermediate morphs constitute 10–20% of the population in the western United States but seem to constitute only 1–2% of B. j. calurus in western Canada.[11][12] A whitish underbelly with a dark brown band across the belly, formed by horizontal streaks in feather patterning, is present in most color variations. This feature is variable in eastern hawks and generally absent in some light subspecies (i.e. B. j. fuertesi).[2] Most adult red-tails have a dark brown nape and upper head which gives them a somewhat hooded appearance, while the throat can variably present a lighter brown “necklace”. Especially in younger birds, the underside may be otherwise covered with dark brown spotting and some adults may too manifest this stippling. The back is usually a slightly darker brown than elsewhere with paler scapular feathers, ranging from tawny to white, forming a variable imperfect “V” on the back. The tail of most adults, which of course gives this species its name, is rufous brick-red above with a variably sized black subterminal band and generally appears light buff-orange from below. In comparison, the typical pale immatures (i.e. less than two years old) typically have a mildly paler headed and tend to show a darker back than adults with more apparent pale wing feather edges above (for descriptions of dark morph juveniles from B. j. calurus, which is also generally apt for description of rare dark morphs of other races, see under that subspecies description). In immature red-tailed hawks of all hues, the tail is a light brown above with numerous small dark brown bars of roughly equal width, but these tend to be much broader on dark morph birds. Even in young red-tails, the tail may be a somewhat rufous tinge of brown.[2][4][13] The bill is relatively short and dark, in the hooked shape characteristic of raptors, and the head can sometimes appear small in size against the thick body frame.[2] The cere, the legs, and the feet of the red-tailed hawk are all yellow, as is the hue of bare parts in many accipitrids of different lineages.[14] Immature birds can be readily identified at close range by their yellowish irises. As the bird attains full maturity over the course of 3–4 years, the iris slowly darkens into a reddish-brown hue, which is the adult eye-color in all races.[4][13] Seen in flight, adults usually have dark brown along the lower edge of the wings, against a mostly pale wing, which bares light brownish barring. Individually, the underwing coverts can range from all dark to off-whitish (most often more heavily streaked with brown) which contrasts with a distinctive black patagium marking. The wing coloring of adults and immatures is similar but for typical pale morph immatures having somewhat heavier brownish markings.[2][15]

Though the markings and hue vary across the subspecies, the basic appearance of the red-tailed hawk is relatively consistent.

Overall, this species is blocky and broad in shape, often appearing (and being) heavier than other Buteos of similar length. They are the heaviest Buteos on average in eastern North America, albeit scarcely ahead of the larger winged rough-legged buzzard (Buteo lagopus), and second only in size in the west to the ferruginous hawk (Buteo regalis). Red-tailed hawks may be anywhere from the fifth to the ninth heaviest Buteo in the world depending on what figures are used. However, in the northwestern United States, ferruginous hawk females are 35% heavier than female red-tails from the same area.[2] On average, western red-tailed hawks are relatively longer winged and lankier proportioned but are slightly less stocky, compact and heavy than eastern red-tailed hawks in North America. Eastern hawks may also have mildly larger talons and bills than western ones. Based on comparisons of morphology and function amongst all accipitrids, these features imply that western red-tails may need to vary their hunting more frequently to on the wing as the habitat diversifies to more open situations and presumably would hunt more variable and faster prey, whereas the birds of the east, which was historically well-wooded, are more dedicated perch hunters and can take somewhat larger prey but are likely more dedicated mammal hunters.[9][16][17] In terms of size variation, red-tailed hawks run almost contrary to Bergmann's rule (i.e. that northern animals should be larger in relation than those closer to the Equator within a species) as one of the northernmost subspecies, B. j. alascensis, is the second smallest race based on linear dimensions and that two of the most southerly occurring races in the United States, B. j. fuertesi and B. j. umbrinus, respectively, are the largest proportioned of all red-tailed hawks.[9][17][18] Red-tailed hawks tend have a relatively short but broad tails and thick, chunky wings.[13] Although often described as long winged,[2][4] the proportional size of the wings is quite small and red-tails have high wing loading for a buteonine hawk. For comparison, two other widespread Buteo hawks in North America were found to weigh: 30 g (1.1 oz) for every square centimeter of wing area in the rough-legged buzzard (Buteo lagopus) and 44 g (1.6 oz) per square cm in the red-shouldered hawk (Buteo lineatus). In contrast, the red-tailed hawk weighed considerably more for their wing area: 199 g (7.0 oz) per square cm.[19]

As is the case with many raptors, the red-tailed hawk displays sexual dimorphism in size, as females are up to 25% larger than males.[14] As is typical in large raptors, frequently reported mean body mass for Red-tailed Hawks are somewhat higher than expansive research reveals.[20] Part of this weight variation is seasonal fluctuations, hawks tending to be heavier in winter than during migration or especially during the trying summer breeding season, and also due to clinal variation. Furthermore, immature hawks are usually lighter in mass than their adult counterparts despite averaging somewhat longer winged and tailed. Male red-tailed hawks may weigh from 690 to 1,300 g (1.52 to 2.87 lb) and females may weigh between 801 and 1,723 g (1.766 and 3.799 lb) (the lowest figure from a migrating female immature from Goshute Mountains, Nevada, the highest from a wintering female in Wisconsin).[5][21][22] Some sources claim the largest females can weigh up to 2,000 g (4.4 lb) but whether this is in reference to wild hawks (as opposed to those in captivity or used for falconry) is not clear.[23] The largest known survey of body mass in red-tailed hawks is still credited to Craighead & Craighead (1956), who found 100 males to average 1,028 g (2.266 lb) and 108 females to average 1,244 g (2.743 lb). However, these figures were apparently taken from labels on museum specimens, apparently from natural history collections in Wisconsin and Pennsylvania, without note to the region, age or subspecies of the specimens.[5][24] However, 16 sources ranging in sample size from the aforementioned 208 specimens to only four hawks in Puerto Rico (with 9 of the 16 studies of migrating red-tails), showed that males weigh a mean of 860.2 g (1.896 lb) and females weigh a mean of 1,036.2 g (2.284 lb), about 15% lighter than prior species-wide published weights. Within the continental United States, average weights of males can range from 840.8 g (1.854 lb) (for migrating males in Chelan County, Washington) to 1,031 g (2.273 lb) (for male hawks found dead in Massachusetts) and females ranged from 1,057.9 g (2.332 lb) (migrants in the Goshutes) to 1,373 g (3.027 lb) (for females diagnosed as B. j. borealis in western Kansas).[20][9][16][25][26][27][28][29] Size variation in body mass reveals that the red-tailed hawks typically varies only a modest amount and that size differences are geographically inconsistent. Racial variation in average weights of great horned owls (Bubo virginianus) show that mean body mass is nearly twice (the heaviest race is about 36% heavier than the lightest known race on average) as variable as that of the hawk (where the heaviest race is only just over 18% heavier on average than the lightest). Also, great horned owls correspond well at the species level with Bergmann’s rule.[9][25]

Male red-tailed hawks can measure 45 to 60 cm (18 to 24 in) in total length, females measuring 48 to 65 cm (19 to 26 in) long. The wingspan typically can range from 105 to 141 cm (3 ft 5 in to 4 ft 8 in), although the largest females may possible span up to 147 cm (4 ft 10 in). In the standard scientific method of measuring wing size, the wing chord is 325.1–444.5 mm (12.80–17.50 in) long. The tail measures 188 to 258.7 mm (7.40 to 10.19 in) in length.[2][21][30] The exposed culmen was reported to range from 21.7 to 30.2 mm (0.85 to 1.19 in) and the tarsus averaged 74.7–95.8 mm (2.94–3.77 in) across the races.[20][9][31] The middle toe (excluding talon) can range from 38.3 to 53.8 mm (1.51 to 2.12 in), with the hallux-claw (the talon of the rear toe, which has evolved to be the largest in accipitrids) measuring from 24.1 to 33.6 mm (0.95 to 1.32 in) in length.[20][9]

Identification

Although they overlap in range with most other American diurnal raptors, identifying most mature red-tailed hawks to species is relatively straightforward, particularly if viewing a typical adult at a reasonable distance. The red-tailed hawk is the only North American hawk with a rufous tail and a blackish patagium marking on the leading edge of its wing (which is obscured only on dark morph adults and Harlan’s hawks by similarly dark colored feathers).[2] Other larger adult Buteo in North America usually have obvious distinct markings that are absent in red-tails, whether the rufous-brown “beard” of Swainson's hawks (Buteo swainsonii) or the colorful rufous belly and shoulder markings and striking black-and-white mantle of red-shouldered hawks (also the small “windows” seen at the end of their primaries).[32] In perched individuals, even as silhouettes, the shape of large Buteos may be distinctive, such as the wingtips overhanging the tail in several other species, but not in red-tails. North American Buteos range from the dainty, compact builds of much smaller Buteos, such as broad-winged hawk (Buteo platypterus) to the heavyset, neckless look of ferruginous hawks or the rough-legged buzzard which has a compact, smaller appearance than a red-tail in perched birds due to its small bill, short neck and much shorter tarsus, while the opposite effect occurs in flying rough-legs with their much bigger wing area.[2][32] In flight, most other large North American Buteo are distinctly longer and slenderer winged than red-tailed hawks, with the much paler ferruginous hawk having peculiarly slender wings in relation to its massive, chunky body. Swainson's hawks are distinctly darker on the wing and ferruginous hawks are much paler winged than typical red-tailed hawks. Pale morph adult ferruginous hawk can show mildly tawny-pink (but never truly rufous) upper tail, and like red-tails tend to have dark markings on underwing-coverts and can have a dark belly band but compared to red-tailed hawks have a distinctly broader head, their remiges are much whiter looking with very small dark primary tips, they lack the red-tail’s diagnostic patagial marks and usually (but not always) also lack the dark subterminal tail-band, and ferruginous have a totally feathered tarsus. With its whitish head, the ferruginous hawk is most similar to Krider's red-tailed hawks, especially in immature plumage, but the larger hawk has broader head and narrower wing shape and the ferruginous immatures are paler underneath and on their legs. Several species share a belly band with the typical red-tailed hawk but they vary from subtle (as in the ferruginous hawk) to solid blackish, the latter in most light-morph rough-legged buzzards.[2][15] More difficult to identify among adult red-tails are its darkest variations, as most species of Buteo in North America also have dark morphs. Western dark morph red-tails (i.e. calurus) adults, however, retain the typical distinctive brick-red tail which other species lack, which may stand out even more against the otherwise all chocolate brown-black bird. Standard pale juveniles when perched show a whitish patch in the outer half of the upper surface of the wing which other juvenile Buteo lack.[4] The most difficult to identify stages and plumage types are dark morph juveniles, Harlan’s hawk and some Krider’s hawks (the latter mainly with typical ferruginous hawks as aforementioned). Some darker juveniles are similar enough to other Buteo juveniles that it has been stated that they "cannot be identified to species with any confidence under various field conditions."[5][4] However, field identification techniques have advanced in the last few decades and most experienced hawk-watchers can distinguish even the most vexingly plumaged immature hawks, especially as the wing shapes of each species becomes apparent after seeing many. Harlan’s hawks are most similar to dark morph rough-legged buzzards and dark morph ferruginous hawks. Wing shape is the most reliable identification tool for distinguishing the Harlan’s from these, but also the pale streaking on the breast of Harlan’s, which tends to be conspicuous in most individuals, and is lacking in the other hawks. Also dark morph ferruginous hawks do not have the dark subterminal band of a Harlan’s hawk but do bear a black undertail covert lacking in Harlan’s.[2][33]

Taxonomy

The red-tailed hawk is a member of the subfamily Buteoninae which includes about 55 currently recognized species.[2][21] Unlike many lineages of accipitrid, which seemed to have radiated out of Africa or south Asia, the Buteoninae clearly originated in the Americas based on fossil records and current species distributions (more than 75% of the extant hawks from this lineage are found in the Americas).[2][34] As a subfamily, the Buteoninae seem to be rather old based on genetic materials, with monophyletic genera baring several million years of individual evolution. Diverse in plumage appearance, habitat, prey and nesting preferences, buteonine hawks are nonetheless typically medium to large sized hawks with ample wings (while some fossil forms are very large, larger than any eagle alive today).[35][36][37] The red-tailed hawk is a member of the genus Buteo, a group of medium-sized raptors with robust bodies and broad wings. Members of this genus are known as buzzards in Eurasia, but hawks in North America.[38] Under current classification, the genus includes approximately 28 species, the second most diverse of all extant accipitrid genera behind only Accipiter. The buzzards of Eurasia and Africa are mostly part of the genus Buteo, although two other small genera within the subfamily Buteoninae occur in Africa.[2][21][39]

At one time, the rufous-tailed hawk (Buteo ventralis), distributed in Patagonia and some other areas of southern South America, was considered part of the red-tailed hawk species. With a massive distributional gap consisting of the majority of South America, the rufous-tailed hawk is considered a separate species now but the two hawks still compromise a “species pair” or superspecies, as they are clearly closely related. The rufous-tailed hawk, while comparatively little studied, is very similar to the red-tailed hawk, being about the same size in body mass and possessing the same wing structure, and having more or less parallel nesting and hunting habits. Physically, however, rufous-tailed hawk adults do not attain a bright brick-red tail as do red-tailed hawks, instead retaining a dark brownish-cinnamon tail with many blackish crossbars similar to juvenile red-tailed hawks.[2][40][41] Another, more well-known, close relative to the red-tailed hawk is the common buzzard (Buteo buteo), which has been considered as its Eurasian “broad ecological counterpart” and may too be within a species complex with red-tailed hawk. The common buzzard, in turn, is also part of a species complex with other Old World buzzards, namely the mountain buzzard (Buteo oreophilus), the forest buzzard (Buteo trizonatus ) and the Madagascar buzzard (Buteo brachypterus).[2][39][42] All six species in the alleged species complex, although varying notably in size and plumage characteristics, that houses red-tailed hawk share with it the feature of the blackish patagium marking, which is missing in most other Buteos.[2][43]

Subspecies

There may be at least 14 recognized subspecies of Buteo jamaicensis, which vary in range and in coloration. However, not all authors accept every subspecies, particularly some of the insular races of the tropics (which differ only slightly in some cases from the nearest mainland forms) and particularly the Krider’s hawks, by far the most controversial red-tailed hawk race as few authors agree on its suitability as a full-fledged subspecies.[5][9][15]

- Jamaican red-tailed hawk (B. j. jamaicensis), the nominate subspecies, occurs in the northern West Indies, including Jamaica, Hispaniola, Puerto Rico and the Lesser Antilles but not the Bahamas or Cuba.

- Alaska red-tailed hawk (B. j. alascensis) breeds (probably resident) from southeastern coastal Alaska to Haida Gwaii and Vancouver Island in British Columbia.

- Eastern red-tailed hawk (B. j. borealis) breeds from southeast Canada and Maine south through Texas and east to northern Florida.

- Western red-tailed hawk (B. j. calurus) seems to have the greatest longitudinal breeding distribution of any race of red-tailed hawk.

- Central American red-tailed hawk (B. j. costaricensis) is resident from Nicaragua to Panama.

- Southwestern red-tailed hawk (B. j. fuertesi) breeds from northern Chihuahua to southern Texas.

- Tres Marias red-tailed hawk (B. j. fumosus) is endemic to Islas Marías, Mexico.

- Mexican Highlands red-tailed hawk (B. j. hadropus) is native to the Mexican Highlands.

- Harlan's hawk (B. j. harlani) breeds from central Alaska to northwestern Canada, with the largest number of birds breeding in the Yukon or western Alaska, reaching their southern limit in north-central British Columbia.

- Red-tailed hawk kemsiesi (B. j. kemsiesi) is a dark subspecies resident from Chiapas, Mexico to Nicaragua.

- Krider's hawk (B. j. kriderii) breeds from southern Alberta, southern Saskatchewan, southern Manitoba, and extreme western Ontario south to south-central Montana, Wyoming, western Nebraska, and western Minnesota.

- Socorro red-tailed hawk (B. j. socorroensis) is endemic to Socorro Island, Mexico.

- Cuban red-tailed hawk (B. j. solitudinis) is native to the Bahamas and Cuba.

- Florida red-tailed hawk (B. j. umbrinus) occurs year-round in peninsular Florida north to as far Tampa Bay and the Kissimmee Prairie south throughout the rest of peninsular Florida down to the Florida Keys.

Distribution and habitat

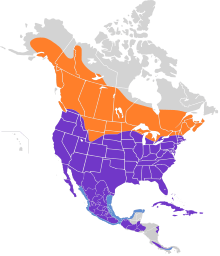

The red-tailed hawk is one of the most widely distributed of all raptors in the Americas. It occupies the largest breeding range of any diurnal raptor north of the Mexican border, just ahead of the American kestrel (Falco sparverius). While the peregrine falcon (Falco peregrinus) has a greater latitudinal distribution as a nester in North America, its range as a breeding species is far more sporadic and sparse than that of red-tailed hawks.[44] The red-tailed hawk breeds from nearly north-central Alaska, the Yukon, and a considerable portion of the Northwest Territories, there reaching as far as a breeder as Inuvik, Mackenzie river Delta and skirting the southern shores of Great Bear Lake and Great Slave Lake. Thereafter in northern Canada, breeding red-tails continue to northern Saskatchewan and across to north-central Ontario east to central Quebec and the Maritime Provinces of Canada, and south continuously to Florida. There are no substantial gaps throughout the entire contiguous United States where breeding red-tailed hawks do not occur. Along the Pacific, their range includes all of Baja California, including Islas Marías, and Socorro Island in the Revillagigedo Islands. On the mainland, breeding red-tails are found continuously to Oaxaca, then experience a brief gap at the Isthmus of Tehuantepec thereafter subsequently continuing from Chiapas through central Guatemala on to north Nicaragua. To the south, the population in highlands from Costa Rica to central Panama is isolated from breeding birds in Nicaragua. Further east, breeding red-tailed hawks occur in the West Indies in north Bahamas (i.e. Grand Bahama, Abaco and Andros) and all larger islands (such as Cuba, Jamaica, Hispaniola and Puerto Rico) and into the northern Lesser Antilles (Virgin Islands, Saint Barthélemy, Saba, Saint Kitts and Nevis, being rare as a resident on Saint Eustatius and are probably extinct on Saint Martin). The typical winter range stretches from southern Canada south throughout the remainder of the breeding range.[2][45][44]

.jpg)

Red-tailed hawks have shown the ability to become habituated to almost any habitat present in North and Central America. Their preferred habitat is mixed forest and field, with trees or alternately high bluffs that may be used as nesting and perching sites. It occupies a wide range of habitats and altitudes, including deserts, grasslands, nearly any coastal or wetland habitat, mountains, foothills, coniferous and deciduous woodlands and tropical rainforests. Agricultural fields and pasture which are more often than not varied with groves, bluffs or streamside trees in most parts of America may make nearly ideal habitat for breeding or wintering red-tails.[1][5][9][15] Some red-tails may survive or even flourish in urban areas.[46] One famous urban red-tailed hawk, known as "Pale Male", became the subject of a non-fiction book, Red-Tails in Love: A Wildlife Drama in Central Park, and is the first known red-tail in decades to successfully nest and raise young in the crowded New York City borough of Manhattan.[47][48][49][50] As studied in Syracuse, New York, the Highway system has been very beneficial to red-tails as it juxtaposed trees and open areas, blocks human encroachment with fences, with the red-tailed hawks easily becoming acclimated to car traffic. The only practice which has a negative effect on the highway-occupying red-tails is the planting of exotic Phragmites, which may occasionally obscure otherwise ideal highway habitat.[51]

In the northern Great Plains, the widespread practices of wildfire suppression and planting of exotic trees by humans has allowed groves of aspen and various other trees to invade what was once vast, almost continuous grasslands, causing grassland obligates like ferruginous hawks to decline and allowing parkland-favoring red-tails to flourish.[5][52] To the contrary, clear-cutting of mature woodlands in New England, resulting in only fragmented and isolated stands of trees or low second growth remaining, was recorded to also benefit red-tailed hawks, despite being to the determent of breeding red-shouldered hawks.[53] The red-tailed hawk, as a whole, is second only to the peregrine falcon and the great horned owl amongst raptorial birds in terms of the use of diverse habitats in North America.[5][54] Beyond the high Arctic (as they discontinuous as a breeder at the tree line), there are few other areas where red-tailed hawks are absent or rare in North and Central America. Some areas of unbroken forest, especially lowland tropical forests, rarely host red-tailed hawks although they can occupy forested tropical highlands surprisingly well. In deserts, they can only occur where there is some variety of arborescent growth or ample rocky bluffs.[11][55][56]

Behavior

The red-tailed hawk is a bird that is highly conspicuous to humans in much of its daily behavior. Most birds in resident populations, which are well more than half of all red-tailed hawks, usually split non-breeding season activity between territorial soaring flight and sitting on a perch. Often perching is for hunting purposes, but many will sit on a tree branch for hours, occasionally stretching on a single wing or leg to keep limber, with no signs of hunting intent.[5][4][53] Wintering typical pale-morph hawks in Arkansas were found to perch in open areas near the top of tall, isolated trees, whereas dark morphs more frequently perched in dense groups of trees.[4] For many, and perhaps most, red-tailed hawks being mobbed by various birds is a daily concern and can effectively disrupt many of their daily behaviors. Mostly larger passerines, of multiple families from tyrant flycatchers to icterids, will mob red-tails, despite that other raptors such as Accipiter hawks and falcons are a notably greater danger to them.[57][58] The most aggressive and dangerous attacker as such is likely to be various crows or other corvids, i.e. American crows (Corvus brachyrhynchos), due to the fact that a mobbing group (or “murder”) of them can number up to as many as 75 crows, which may cause grievous physical harm to a solitary hawk and, if the hawks are nesting, separate the parent hawks and endanger the eggs or nestlings within their nest to predation by the murder of crows.[59][60] However, evidence has shown that birds that mob red-tailed hawks can tell how distended the hawk's crop is (i.e. the upper chest and throat area being puffy versus flat-feathered and sleek) and thus mob more often when the hawk is presumably about to hunt.[61]

Flight

.jpg)

In flight, this hawk soars with wings often in a slight dihedral, flapping as little as possible to conserve energy. Soaring is by far the most efficient method of flight for red-tailed hawks and is used more often than not.[62] Active flight is slow and deliberate, with deep wing beats. Wing beats are somewhat less rapid in active flight than in most other Buteo hawks, even heavier species such as ferruginous hawks tend to flap more swiftly, due to the morphology of the wings.[63] In wind, it occasionally hovers on beating wings and remains stationary above the ground, but this flight method is rarely employed by this species.[9][11] When soaring or flapping its wings, it typically travels from 32 to 64 km/h (20 to 40 mph), but when diving may exceed 190 km/h (120 mph).[64] Although North American red-tailed hawks will occasionally hunt from flight, a great majority of flight by red-tails in this area is for non-hunting purpose.[62] During nest defense, red-tailed hawks may be capable of surprisingly swift, vigorous flight while repeatedly diving at perceived threats.[65]

Vocalization

The cry of the red-tailed hawk is a two to three second hoarse, rasping scream, variously transcribed as kree-eee-ar, tsee-eeee-arrr or sheeeeee,[46] that begins at a high pitch and slurs downward.[2][15][64] This cry is often described as sounding similar to a steam whistle.[14][15] The red-tailed hawk frequently vocalizes while hunting or soaring, but vocalizes loudest and most persistently in defiance or anger, in response to a predator or a rival hawk's intrusion into its territory.[15][46] At close range, it makes a croaking guh-runk, possibly as a warning sound.[66] Nestlings may give peeping notes with a "soft sleepy quality" that give way to occasional screams as they develop, but those are more likely a soft whistle than the harsh screams of the adults. Their latter hunger call, given anywhere from 11 days (as recorded in Alaska) to post-fledgling (in California), is different, a two syllabled, wailing klee-uk food cry exerted by the young when parents leave the nest or enter their field of vision.[5][67] A strange mechanical sound "not very unlike the rush of distant water" has been reported as uttered in the midst of a sky-dance.[5] A modified call of chirp-chwirk is given during courtship while a low key, duck-like nasal gank may be given by pairs when they are relaxed.[15] The fierce, screaming cry of the red-tailed hawk is frequently used as a generic raptor sound effect in television shows and other media, even if the bird featured is not a red-tailed hawk.[68][69] It is especially used in depictions of the bald eagle.

Migration

Red-tailed hawks are considered partial migrants, as in about the northern-third of their distribution, which is most of their range in Canada and Alaska, they almost entirely vacate their breeding grounds.[2][9] In coastal areas of the north, however, such as in the Pacific northwest up to southern Alaska and in Nova Scotia on the Atlantic, red-tailed hawks do not usually migrate.[5] More or less, any area where snow cover is nearly continuous during the winter months will show an extended absence of most red-tailed hawks, so some areas as far south as Montana may show strong seasonal vacancies of red-tails.[5] In southern Michigan immature red-tailed hawks tended to remain in winter only when voles were abundant. During relatively long harsh winters up in Michigan, many more young ones were reported in northeastern Mexico.[5][24] To the opposite extreme, hawks residing as far north as Fairbanks in Alaska may persevere through the winter on their home territory, as was recorded with one male over three consecutive years.[70] Birds of any age tend to be territorial during winter but may shift ranges whenever food requirements demand it.[5] Wintering birds tend to perch on inconspicuous tree perches, seeking shelter especially if they have a full crop or are in the midst of poor or overly windy weather. Adult wintering red-tails tend to perch more prominently than immatures do, which select lower or more secluded perches. Immatures are often missed in winter bird counts, unless they are being displaced by dominant adults. Generally though, immatures can seem to recognize that they are less likely to be attacked by adults during winter and can perch surprisingly close to them. Age is the most significant consideration of wintering hawks’ hierarchy but size does factor in, as larger immatures (presumably usually females) are less likely to displaced than smaller ones.[4][5][9] Dark adult red-tailed hawks appear to be harder to locate when perched than other red-tails. In Oklahoma, for example, wintering adult Harlan's hawks were rarely engaged in fights or chased by other red-tails. These Harlan's tended to gather in regional pockets and frequently the same Harlan’s occurred year-to-year.[70] In general, migratory behavior is complex and reliant on each individual hawks’ decision-making (i.e. whether prey populations are sufficient enough to entice the hawk to endure prolonged snow cover).[9] During fall migration, departure may occur as soon as late September but peak movements occur in late October and the full month of November in the United States, with migration ceasing after mid-December. The northernmost migrants may pass over resident red-tailed hawks in the contiguous United States while the latter are still in the midst of brooding fledglings.[5] Not infrequently several autumn hawk-watches in Ontario, Quebec and the northern United States will record 4,500–8,900 red-tailed hawks migrating through each fall, with records of up to 15,000 in a season at Hawk Ridge hawk watch in Duluth, Minnesota.[2][71] Unlike some other Buteos, such as Swainson's hawks and broad-winged hawks (Buteo platypterus), red-tailed hawks do not usually migrate in groups, instead passing by one-by-one, and will only migrate on days when winds are favorable.[2][5] Most migrants do not go past southern Mexico in late autumn, but a few may annually move down as far as to roughly as far as there are breeding red-tailed hawks down in Panama. However, there are now a few records of wintering migrant red-tails turning up in Colombia, the first records of the species in that country or anywhere in South America.[2][9][72] Spring northward movements may commence as early as late February, with peak numbers usually occurring in late March and early April. Seasonal counts may include up to 19,000 red-tails in spring at Derby Hill hawk watch, in Oswego, New York, sometimes more than 5,000 are recorded in a day there.[2][73] The very most northerly migratory individuals may not reach breeding grounds until June, even adults.[2][70]

Immature hawks migrate later than adults in spring on average but not, generally speaking, in autumn. In the northern Great Lakes, immatures return in late May to early June, when adults are already well into their nesting season and must find unoccupied ranges.[5] However, in Alaska adults tend to migrate before immatures in early to mid-September, to the contrary of other areas, probably as heavy snow fall begins.[70][74] Yearlings that were banded in southwestern Idaho stayed for about 2 months after fledging, and then traveled long distances with a strong directional bias, with 9 of 12 recovered southeast of the study area- six of these moved down to coastal lowlands in Mexico and down to as far as Guatemala, here 4,205 km (2,613 mi) from their initial banding.[75] In California, 35 hawks were banded as nestlings, 26 were recovered at less than 50 miles away, with multi-directional juvenile dispersals. Nestlings banded in southern California sometimes actually traveled up to as far as 1,190 km (740 mi) north to Oregon ranging to the opposite extreme as far as a banded bird from the Sierra Nevadas that moved 1,700 km (1,100 mi) south to Sinaloa.[5][76] Nestlings banded in Green County, Wisconsin did not travel very far comparatively by October–November, but just a month later in December recoveries were found in varied states including Illinois, Iowa, Texas, Louisiana and Florida.[77]

Dietary biology

The red-tailed hawk is carnivorous, and a highly opportunistic feeder. It is said that nearly any small animal they encounter may be viewed as potential food.[4] Their most common prey are small mammals such as rodents and lagomorphs, but they will also consume birds, reptiles, fish, amphibians and invertebrates. Prey varies considerably with regional and seasonal availability, but usually centers on rodents, accounting for up to 85% of a hawk's diet.[14] In total nearly 500 prey species have been recorded in their diet, almost as many as the great horned owl have been recorded as taking.[9][53][78][79] When 27 North American studies are reviewed, mammals make up 65.3% of the diet by frequency, 20.9% by birds, 10.8% by reptiles, 2.8% by invertebrates and 0.2% by amphibians and fish.[5][4][78][79] The geometric mean body mass of prey taken by red-tailed hawks in North America averages about 187 g (6.6 oz) based on a pair of compilation studies from across the continent, regionally varying at least from 43.4 to 361.4 g (1.53 to 12.75 oz).[80][81] Staple prey (excluding invertebrates) has been claimed to weigh from 15 to 2,114 g (0.033 to 4.661 lb), ranging roughly from the size of a small mouse or lizard to the size of a black-tailed jackrabbit (Lepus californicus).[5][9][82] The daily food requirements range from 7 to 11.2% of their own body weight, so that about three voles or an individual prey of equivalent weight are required daily for an average range adult.[24]

The talons and feet of red-tailed hawks are relatively large for a Buteo hawk, in an average sized adult red-tail the “hallux-claw” or rear talon, the largest claw on all accipitrids, averages about 29.7 mm (1.17 in).[16][83] In fact, the talons of red-tails in some areas averaged of similar size to those of ferruginous hawks which can be considerably heavier and notably larger than those of the only slightly lighter Swainson's hawk.[16][84][85] This species may exert an average of about 91 kg (201 lb) of pressure per square inch (PSI) through its feet.[16][86][87] Owing to its morphology, red-tailed hawks generally can attack larger prey than other Buteo hawks typically can and are capable of selecting the largest prey of up to their own size available at the time that they are hunting, though in all likelihood numerically most prey probably weighs about 20% of the hawk's own weight (as is typical of many birds of prey).[9][24][88] Red-tailed hawks usually hunt by watching for prey activity from a high perch, also known as still hunting. Upon being spotted, prey is dropped down upon by the hawk. Red-tails often select the highest available perches within a given environment since the greater the height they are at, the less flapping is required and the faster the downward glide they can attain toward nearby prey. If prey is closer than average, the hawk may glide at a steep downward angle with few flaps, if farther than average, it may flap a few swift wingbeats alternating with glides. Perch hunting is the most successful hunting method generally speaking for red-tailed hawks and can account for up to 83% of their daily activities (i.e. in winter).[9][5][89] Wintering pairs may hunt together and aseasonally may join together to group hunt agile prey that they may have trouble catching by themselves, such as tree squirrels. This may consist of stalking opposites sides of a tree, in order to surround the squirrel and almost inevitably drive the rodent to be captured by one after being flushed by the other hawk.[5][15]

_-diving.jpg)

The most common flighted hunting method for red-tail is to cruise approximately 10 to 50 m (33 to 164 ft) over the ground with flap-and-glide type flight, interspersed occasionally with harrier-like quarters over the ground. This method is less successful than perch hunting but seems relatively useful for capturing small birds and may be show the best results while hunting in hilly country.[2][5][15] Hunting red-tailed hawks readily will use trees, bushes or rocks for concealment before making a surprise attack, even showing a partial ability to dodge among trees in an Accipiter-like fashion. Among thick stands of spruce in Alaska, a dodging hunting flight was thought to be unusually important to red-tails living in extensive areas of conifers, with hawks even coming to the ground and walking hurriedly in prey pursuit especially if the prey was large, a similar behavior to goshawks.[5][70] Additional surprisingly swift aerial hunting has reported in red-tails who habitually hunt bats in Texas. Here the bat-hunting specialists would stoop with half-close wings, quite falcon-like, plowing through the huge stream of bats exiting their cave roosts, then zooming upwards with a bat in its talons. These hawks would also fly parallel closely to the stream, then veer sharply into it and seize a bat.[90][91][92] In the neotropics, red-tails have shown the ability to dodge amongst forest canopy whilst hunting.[2][93] In Kansas, red-tailed hawks were recorded sailing to catch flying insects, a hunting method more typical of a Swainson's hawk.[94] Alternately, they may drop to the ground to forage for insects like grasshoppers and beetles as well as other invertebrates and probably amphibians and fish (except by water in the latter cases). Hunting afoot seems to be particularly prevalent among immatures. Young red-tailed hawks in northeastern Florida were recorded often extracting earthworms from near the surface of the ground and some had a crop full of earthworms after rains. Ground hunting is also quite common on Socorro Island, where there are no native land mammals and invertebrates are more significant to their overall diet.[2][5][95] A red-tailed hawk was observed to incorporate an unconventional killing method which was drowning a heron immediately after capture.[96] One red-tailed hawk was seen to try to grab a young ground squirrel and, upon missing it, screamed loudly, which in turn caused another young squirrel to break into a run wherein it was captured. Whether this was an intentional hunting technique needs investigation.[15] Upon capture, smaller prey is taken to a feeding perch, which is almost always lower than a hunting perch. Among small prey, rodents are often swallowed whole as are shrews and small snakes, while birds are plucked and beheaded. Even prey as small as chipmunks may take two to three bites to consume. Larger mammals of transportable size are at times beheaded and have part of their fur discarded, then leftovers are either stored in a tree or fall to the ground. Large prey, especially if too heavy to transport on the wing, is often dragged to a secluded spot and dismantled in various ways. If they can successfully carry what remains to a low perch, they tend to feed until full and then discard the rest.[5][4][15]

Mammals

Rodents are certainly the type of prey taken most often by frequency but their contribution to prey biomass at nests can be regionally low, and the type, variety and importance of rodent prey can be highly variable. In total, well over 100 rodent species have turned up the diet of red-tailed hawks.[9][78][79] Rodents of extremely varied sizes may be hunted by red-tails, with species ranging in size from the 8.2 g (0.29 oz) eastern harvest mouse (Reithrodontomys humulis) to marmots (Marmota ssp.), weighing some 3,300 g (7.3 lb) in spring, although whether they can take full grown marmots is questionable. At least some attacks on adult marmots like groundhogs (Marmota monax) are abortive.[97][98][99] At times, the red-tailed hawk is thought of as a semi-specialized vole-catcher, but voles are a subsistence food that are more or less are taken until larger prey can be captured. In an area of Michigan, immature hawks took almost entirely voles but adults were diversified feeders.[5][24] Indeed, the 44.1 g (1.56 oz) meadow vole (Microtus pennsylvanicus) was the highest frequency prey species in 27 dietary studies across North America, accounting for up to 54% of the food at nests by frequency. It is quite rare for any one species to make up more than half of the food at any dietary study for red-tailed hawks.[5][4][78][79][100][101] In total about 9 Microtus species are known in the overall diet, with 5 other voles and lemmings known to be included in their prey spectrum.[78][79] Another well-represented species was the 27.9 g (0.98 oz) prairie vole (Microtus ochrogaster), which were the primary food, making up 26.4% of a sample of 1322, in eastern Kansas.[102] While crepuscular in primary feeding activity, voles are known to be active both day and night, and so are reliable food for hawks than most non-squirrel rodents, which generally are nocturnal in activity.[24][103][104] Indeed, most other microtine rodents are largely inaccessible to red-tailed hawks due to their strongly nocturnal foraging patterns, even though 24 species outside of voles and lemmings are known to be hunted. Woodrats are taken as important supplemental prey in some regions, being considerably larger than most other crictetid rodents, and some numbers of North American deermouse (Peromyscus maniculatus) may turn up. The largest representation of the latter species was contributing 11.9% of the diet in the Great Basin of Utah, making them the second best represented prey species there.[78][105] Considering this limited association with nocturnal rodents, the high importance of pocket gophers in the diet of red-tailed hawks is puzzling to many biologists, as these tend to be highly nocturnal and elusive by day, rarely leaving the confines of their burrow. At least 8 species of pocket gopher are included in the prey spectrum (not to mention 5 species of pocket mice). The 110 g (3.9 oz) northern pocket gopher (Thomomys talpoides) is particularly often reported and, by frequency, even turns up as the third most often recorded prey species in 27 American dietary studies. Presumably, hunting of pocket gophers by red-tails, which has possibly never been witnessed, occurs in dim light at first dawn and last light of dusk when they luck upon a gopher out foraging.[5][78][79][106][107]

By far, the most important prey among rodents are squirrels, as they are almost fully diurnal. All told, nearly 50 species from the squirrel family have turned up as food. In particular, where they are distributed, ground squirrels are doubly attractive as a primary food source due to their ground dwelling habits, as red-tails prefer to attack prey that is terrestrial.[9][5][78][79] There are also many disadvantages to ground squirrels as prey: they can escape quickly to the security of their burrows, they tend to be highly social and they are very effective and fast in response to alarm calls, and a good deal of species enter hibernation that in the coldest climates can range up to a 6 to 9-month period (although those in warmer climates with little to no snowy weather often have brief dormancy and no true hibernation). Nonetheless, red-tailed hawks are devoted predators of ground squirrels, especially catching incautious ones as they go out foraging (which more often than not are younger animals).[108][109][110][111] A multi-year study conducted on San Joaquin Experimental Range in California, seemingly still the largest food study to date done for red-tailed hawks with 4031 items examined, showed that throughout the seasons the 722 g (1.592 lb) California ground squirrel (Otospermophilus beecheyi) was the most significant prey, accounting for 60.8% of the breeding season diet and about 27.2% of the diet for hawks year-around. Because of the extremely high density of red-tailed hawks on this range, some pairs came to specialize on diverse alternate prey, which consisted variously of kangaroo rats, lizards, snakes or chipmunks. One pair apparently lessened competition by focusing on pocket gophers instead despite being near the center of ground squirrel activity.[112][113] In Snake River NCA, the primary food of red-tailed hawks was the 203.5 g (7.18 oz) Townsend's ground squirrel (Urocitellus townsendii), which made up nearly 21% of the food in 382 prey items across several years despite sharp spikes and crashes of the ground squirrel population there.[82][114] The same species was the main food of red-tailed hawks in southeastern Washington, making up 31.2% of 170 items.[115] An even closer predatory relationship was reported in the Centennial valley of Montana and south-central Montana, where 45.4% of 194 prey items and 40.2% of 261 items, respectively, of the food of red-tails consisted of the 455.7 g (1.005 lb) Richardson's ground squirrel (Urocitellus richardsonii).[84][116][117] Locally in Rochester, Alberta, Richardson's ground squirrel, estimated to average 444 g (15.7 oz), were secondary in number to unidentified small rodents but red-tails in the region killed an estimated 22–60% of the area’s ground squirrel, a large dent in the squirrel’s population.[118] Further east, ground squirrels are not so reliably distributed, but one study in southern Wisconsin, in one of several quite different dietary studies in that state, the 172.7 g (6.09 oz) thirteen-lined ground squirrel (Ictidomys tridecemlineatus) was the main prey species, making up 29.7% of the diet (from a sample of 165).[119][120]

In Kluane Lake, Yukon, 750 g (1.65 lb) Arctic ground squirrels (Spermophilus parryii) were the main overall food for Harlan’s red-tailed hawks, making up 30.8% of a sample of 1074 prey items. When these ground squirrels enter their long hibernation, the breeding Harlan’s hawks migrate south for the winter.[121] Nearly as important in Kluane Lake was the 200 g (7.1 oz) American red squirrel (Tamiasciurus hudsonicus), which constituted 29.8% of the above sample. Red squirrels are highly agile dwellers on dense spruce stands, which has caused biologists to ponder how the red-tailed hawks are able to routinely catch them. It is possible that the hawks catch them on the ground such as when squirrels are digging their caches, but theoretically the dark color of the Harlan’s hawks may allow them to more effectively ambush the squirrels within the forests locally.[5][120][121] While American red squirrel turn up not infrequently as supplementary prey elsewhere in North America, other tree squirrels seem to be comparatively infrequently caught, at least during the summer breeding season. It is known that pairs of red-tailed hawks will cooperative hunt tree squirrels at times, probably mostly between late fall and early spring. Fox squirrels (Sciurus niger), the largest of North America’s tree squirrels at 800 g (1.8 lb), are fairly regular supplemental prey but the lighter, presumably more agile 533 g (1.175 lb) eastern gray squirrel (Sciurus carolinensis) appears to be seldom caught based on dietary studies.[9][77][119][120][122] While adult marmot may be difficult for red-tailed hawks to catch, young marmots are readily taken in numbers after weaning, such as a high frequency of yellow-bellied marmot (Marmota flaviventris) in Boulder, Colorado.[123] Another grouping of squirrels but at the opposite end of the size spectrum for squirrels, the chipmunks are also mostly supplemental prey but are considered more easily caught than tree squirrels, considering that they are more habitual terrestrial foragers.[5][4][78] In central Ohio, eastern chipmunks (Tamias striatus), the largest species of chipmunk at an average weight of 96 g (3.4 oz), were actually the leading prey by number, making up 12.3% of a sample of 179 items.[122][124]

Outside of rodents, the most important prey for North American red-tailed hawks is rabbits and hares, of which at least 13 species are included in their prey spectrum. By biomass and reproductive success within populations, these are certain to be the most significant food source to the species (at least in North America).[9][78] Adult Sylvilagus rabbits known to be hunted by red-tails can range from the 700 g (1.5 lb) brush rabbit (Sylvilagus bachmani) to the Tres Marias rabbit (Sylvilagus graysoni) at 1,470 g (3.24 lb) while all leporids hunted may range the 421.3 g (14.86 oz) pygmy rabbit (Brachylagus idahoensis) to hares and jackrabbits potentially up twice the hawk’s own weight.[125][126][127][27] While primarily crepuscular in peak activity, rabbits and hares often foraging both during day and night and so face almost constant predatory pressure from a diverse range of predators. Male red-tailed hawks or pairs which are talented rabbit hunters are likely have higher than average productivity due to the size and nutrition of the meal ensuring healthy, fast-growing offspring.[5][9][24][128] Most widely reported are the cottontails, which the three most common North America varieties softly grading into mostly allopatric ranges, being largely segregated by habitat preferences where they overlap in distribution. Namely, in descending order of reportage were: the eastern cottontail (Sylvilagus floridanus), the second most widely reported prey species overall in North America and with maximum percentage known in a given study was 26.4% in Oklahoma (out of 958 prey items), the mountain cottontail (Sylvilagus nuttallii), maximum representation being 17.6% out of a sample of 478 in Kaibab Plateau, Arizona and the desert cottontail (Sylvilagus audubonii), maximum representation being 22.4% out of a sample of 326 in west-central Arizona.[78][116][129][130] Black-tailed jackrabbits (Lepus californicus) are even more intensely focused upon as a food source by the hawks found in the west, particularly the Great Basin. This species is likely the largest prey routinely hunted by red-tails and the mean prey size where jackrabbits are primarily hunted is indeed the highest known overall in the species. When jackrabbit numbers crash, red-tailed hawk productivity tends to decline synchronically. In northern Utah, black-tailed jackrabbits made up 55.3% by number of a sample of 329. Elsewhere, they are usually somewhat secondary by number. Mean sizes of jackrabbits taken can range up to approximately 2,114 g (4.661 lb), but probably quantitatively mostly juvenile and yearling jackrabbits are caught. Prime adult jackrabbits, with weights at times exceeding 2,700 g (6.0 lb), are difficult and taken infrequently, short of by particularly large and aggressive female red-tails.[78][115][82][105] Other even larger species are sometimes taken as prey such as the white-tailed jackrabbit (Lepus townsendii), but whether this includes healthy adults, as they average over 3,200 g (7.1 lb), is unclear.[84]

.jpg)

In the boreal forests of Canada and Alaska, red-tails are fairly dependent on the snowshoe hare (Lepus americanus), falling somewhere behind the great horned owl and ahead of the northern goshawk in their regional reliance on this food source.[70][121][118] The hunting preferences of red-tails who rely on snowshoe hares is variable. In Rochester, Alberta, 52% of snowshoe hares caught were adults, such prey estimated to average 1,287 g (2.837 lb), and adults, in some years, were six times more often taken than juvenile hares, which averaged an estimated 560 g (1.23 lb). 1.9–7.1% of adults in the regional population of Rochester were taken by red-tails, while only 0.3–0.8 of juvenile hares were taken by them. Despite their reliance on it, only 4% (against 53.4% of the biomass) of the food by frequency here was made up of hares.[118] On the other hand, in Kluane, Yukon, juvenile hares were taken roughly 11 times more often than adults, despite the larger size of adults here, averaging 1,406.6 g (3.101 lb), and that the overall prey base was less diverse at this more northerly clime. In both Rochester and Kluane Lake, the number of snowshoe hares taken was considerably lower than numbers of ground squirrels taken. The differences of average characteristics of snowshoe hares that were hunted may be partially due to habitat (extent of bog openings to dense forest) or topography.[121][131] Another member of the Lagomorpha order has been found in the diet, the much smaller American pika (Ochotona princeps), at 150 g (5.3 oz), but is not quantitatively common in the foods of the species so far as is known.[132]

A diversity of mammals may be consumed opportunistically outside of the main food groups of rodents and leporids, but usually occur in low numbers. At least five species each are taken of shrews and moles, ranging in size from their smallest mammalian prey, the cinereus (Sorex cinereus) and least shrews (Cryptotis parva), which both weigh about 4.4 g (0.16 oz), to Townsend's mole (Scapanus townsendii), which weighs about 126 g (4.4 oz).[78][79][133][134][135][136] A respectable number of the 90 g (3.2 oz) eastern mole (Scalopus aquaticus) were recorded in studies from Oklahoma and Kansas.[78][102] Four species of bat have been recorded in their foods.[78][112] The red-tailed hawks local to the large cave colonies of 12.3 g (0.43 oz) Mexican free-tailed bats (Tadarida brasiliensis) in Texas can show surprising agility, some of the same hawks spending their early evening and early morning hours in flight patrolling the cave entrances in order to stoop suddenly on these flighted mammals.[90][91][137] Larger miscellaneous mammalian prey are either usually taken as juveniles, like the nine-banded armadillo (Dasypus novemcinctus), or largely as carrion, like the Virginia opossum (Didelphis virginiana).[136][138] Small carnivorans may be taken, usually consisting of much smaller mustelids, like the 150.6 g (5.31 oz) long-tailed weasel (Mustela frenata), which was surprisingly widely taken as a supplemental prey species.[93][78][82][120][139] Adult ringtails (Bassariscus astutus), which are about the same weight as a red-tailed hawk at 1,015 g (2.238 lb), are taken as prey occasionally.[129] Larger carnivoran remains are sometimes found amongst their foods, but most are likely taken as juveniles or smaller range adults, or otherwise consumed only as carrion. Some of the relatively larger carnivorans red-tailed hawks have been known to eat have included red fox ( Vulpes vulpes), kit fox (Vulpes macrotis), white-nosed coati (Nasua narica), raccoon (Procyon lotor), striped skunk (Mephitis mephitis) and domestic cats (Felis silvestris catus).[79][123][140][141][142] Many of these medium-sized carnivorans are probably visited as roadkill, especially during the sparser winter months, but carrion has turned up more widely than previously thought. Some nests have been found (to the occasional “shock” of researchers) with body parts from large domestic stock like sheep (Ovis aries), pigs (Sus scrofa domesticus), horses (Equus caballus ferus) and cattle (Bos primigenius taurus) (not to mention wild varieties like deer), which red-tails must visit when freshly dead out on pastures and take a couple talonfuls of meat.[5][129][112][140] In one instance, a red-tailed hawk was observed to kill a small but seemingly healthy lamb. These are born heavier than most red-tails at 1,500 g (3.3 lb) but in this instance, the hawk was scared away before it could consume its kill by the rifle fire of the shepherd who witnessed the instance.[143]

Birds

Like most (but not all) Buteo hawks, red-tailed hawks do not primarily hunt birds in most areas, but can take them fairly often whenever they opportune upon some that are vulnerable. Birds are, by far, the most diverse class in the red-tailed hawk’s prey spectrum, with well over 200 species known in their foods.[53][78][79] In most circumstances where birds become the main food of red-tailed hawks, it is in response to ample local populations of galliforms. As these are meaty, mostly terrestrial birds which usually run rather than fly from danger (although all wild species in North America are capable of flight), galliforms are ideal avian prey for red-tails. Some 23 species of galliforms are known to be taken by red-tailed hawks, about a third of these being species introduced by humans.[78][79] Native quails of all five North American species may expect occasional losses.[112][144][145] All 12 species of grouse native to North America are also occasionally included in their prey spectrum.[121][84][146][147][148][149][150][151][152] In the state of Wisconsin, two large studies, from Waupun and Green County, found the main prey species to be the ring-necked pheasant (Phasianus colchicus), making up 22.7% of a sample of 176 and 33.8% of a sample of 139, respectively.[77][153] With a body mass averaging 1,135 g (2.502 lb), adult pheasants are among the largest meals that male red-tails are likely to deliver short of adult rabbits and hares and therefore these nests tend to be relatively productive. Despite being not native to North America, pheasants usually live in a wild state. All Wisconsin studies also found large numbers of chickens (Gallus gallus domesticus), making up as much as 14.4% of the diet. Many studies reflect that free-ranging chickens are vulnerable to red-tailed hawks although somewhat lesser numbers are taken by them overall in comparison to nocturnal predators (i.e. owls and foxes) and goshawks.[77][81][153] In Rochester, Alberta, fairly large numbers of ruffed grouse (Bonasa umbellus) were taken but relatively more juveniles were taken of this species than the two other main contributors to biomass here, snowshoe hare and Townsend’s ground squirrel, as they are fairly independent early on and more readily available. Here the adult grouse was estimated to average 550 g (1.21 lb) against the average juvenile which in mid-summer averaged 170 g (6.0 oz).[118]

Beyond galliforms, three other quite different families of birds make the most significant contributions to the red-tailed hawk’s avian diet. None of these three families are known as particularly skilled or swift fliers but the species are generally small enough that they would generally easily be more nimble in flight than a red-tailed hawk. One of these are the woodpeckers, if only for one species, the 131.6 g (4.64 oz) northern flicker (Colaptes auratus), which was the best represented bird species in the diet in 27 North American studies and was even the fourth most often detected prey species of all.[5][4][78][79] Woodpeckers are often a favorite in the diet of large raptors as their relatively slow, undulating flight makes these relatively easy targets. The flicker in particular is a highly numerous species that has similar habitat preferences to red-tailed hawks, preferring fragmented landscapes with trees and openings or parkland-type wooded mosaics, and often forage on the ground for ants, which may make them even more susceptible.[154][155] Varied other woodpecker species may turn up in their foods, from the smallest to the largest extant in North America, but are much more infrequently detected in dietary studies.[136][156] Another family relatively often selected prey family are corvids, which despite their relatively large size, formidable mobbing abilities and intelligence are also slower than average fliers for passerines. 14 species of corvid are known to fall prey to red-tailed hawks.[78][79][157] In the Kaibab Plateau, the 128 g (4.5 oz) Steller's jay (Cyanocitta stelleri) were the fourth most identified prey species (10.3% of the diet).[129] 453 g (0.999 lb) American crows are also regularly detected supplemental prey in several areas.[77][116][153] Even the huge common raven (Corvus corax), at 1,050 g (2.31 lb) at least as large as red-tailed hawk itself, may fall prey to red-tails, albeit very infrequently and only in a well-staged ambush.[129] One of the most surprising heavy contributors are the icterids, despite their slightly smaller size and tendency to travel in large, wary flocks, 12 species are known to be hunted.[78][79] One species pair, the meadowlarks, are most often selected as they do not flock in the same ways as many other icterids and often come to the ground, throughout their life history, rarely leaving about shrub-height. The 100.7 g (3.55 oz) western meadowlark (Sturnella neglecta), in particular, was the third most often detected bird prey species in North America.[5][4][78][79][82] Red-winged blackbirds (Agelaius phoeniceus) which are probably too small, at an average weight of 52.4 g (1.85 oz), and fast for a red-tailed hawk to ever chase on the wing (and do travel in huge flocks, especially in winter) are nonetheless also quite often found in their diet, representing up to 8% of the local diet for red-tails. It is possible that males, which are generally bold and often select lofty perches from which to display, are most regularly ambushed.[5][153] One bird species that often flocks with red-winged blackbirds in winter is even better represented in the red-tail’s diet, the non-native 78 g (2.8 oz) European starling (Sturnus vulgaris), being the second most numerous avian prey species and seventh overall in North America.[78][79] Although perhaps most vulnerable when caught unaware while calling atonally on a perch, a few starlings (or various blackbirds) may be caught by red-tails which test the agile, twisting murmurations of birds by flying conspicuously towards the flock, to intentionally disturb them and possibly detect lagging, injured individual birds that can be caught unlike healthy birds. However, this behavior has been implied rather than verified.[5][112]

Over 50 passerine species from various other families beyond corvids, icterids and starlings are included in the red-tailed hawks’ prey spectrum but are caught so infrequently as to generally not warrant individual mention.[78][79] Non-passerine prey taken infrequently may include but are not limited to pigeons and doves, cuckoos, nightjars, kingfishers and parrots.[9][82][112][158][159][160][161] However, of some interest, is the extreme size range of birds that may be preyed upon. Red-tailed hawks in Caribbean islands seem to catch small birds more frequently due to the paucity of vertebrate prey diversity here. Birds as small as the 7.7 g (0.27 oz) elfin woods warbler (Setophaga angelae) and the 10 g (0.35 oz) bananaquit (Coereba flaveola) may turn up not infrequently as food. How red-tails can catch prey this small and nimble is unclear (perhaps mostly the even smaller nestlings or fledglings are depredated).[5][9][93] In California, most avian prey was stated to be between the size of a starling and a quail.[5][112] Numerous water birds may be preyed upon including at least 22 species of shorebirds, at least 17 species of waterfowl, at least 8 species of heron and egrets and at least 8 species of rails, plus a smaller diversity of grebes, shearwaters and ibises.[5][78][79][162] These may range to as small as the tiny, mysterious and “mouse-like” black rail (Laterallus jamaicensis), weighing an average of 32.7 g (1.15 oz), and snowy plover (Charadrius nivosus), weighing an average of 42.3 g (1.49 oz) (how they catch adults of this prey is not known), to some gulls, ducks and geese as heavy or heavier than a red-tailed hawk itself.[163][164]

How large of a duck that red-tailed hawks can capture may be variable. In one instance, a red-tailed hawk failed to kill a healthy drake red-breasted merganser (Mergus serrator), with this duck estimated to weigh 1,100 g (2.4 lb), later the same red-tail was able to dispatch a malnourished red-necked grebe (Podiceps grisegena) (a species usually about as heavy as the merganser), weighing an estimated 657 g (1.448 lb).[165] However, in interior Alaska, locally red-tailed hawks have become habitual predators of adult ducks, ranging from 345 g (12.2 oz) green-winged teal (Anas carolinensis) to 1,141 g (2.515 lb) mallard (Anas platyrhynchos).[70] Even larger, occasionally adult Ross's goose (Chen rossii), weighing on average 1,636 g (3.607 lb), have been killed as well.[166] Also, a non-native Egyptian goose (Alopochen aegyptiaca), in which adults average 1,762 g (3.885 lb), was killed by a red-tail in Texas.[167] There are several known instances of predation on adult greater sage grouse (Centrocercus urophasianus), although mainly females are reported taken, these averaging 1,200 to 1,745 g (2.646 to 3.847 lb) depending on region. Some adult male sage grouse may have been attacked but, as these average from 2,100 to 3,190 g (4.63 to 7.03 lb), this needs verification.[146] Even larger, in at least once case a grown hatch-year bird was caught of the rare, non-native Himalayan snowcock (Tetraogallus himalayensis), this species averaging 2,428 g (5.353 lb) in adults.[168] Red-tailed hawks are a threat to the poults typically of the wild turkey (Meleagris gallopavo). However, in one instance, an immature red-tail was observed trying to attack an adult female turkey, which would weigh about 4,260 g (9.39 lb) (on average). However this red-tail was unable to overpower the turkey hen.[169] Additionally, young domestic turkeys, weighing up to at least 1,500 g (3.3 lb) or more, have been killed by red-tailed hawks.[170] Other than wild turkeys, other larger birds occasionally lose young to red-tails such as trumpeter swans (Cygnus buccinator), sandhill cranes (Grus canadensis) and great blue herons (Ardea herodias).[171][172]

Reptiles

.jpg)

Early reports claimed relatively little predation of reptiles by red-tailed hawks but these were regionally biased towards the east coast and the upper Midwest of the United States.[173] However, locally the predation on reptiles can be regionally quite heavy and they may become the primary prey where large, stable numbers of rodents and leporids are not to be found reliably. Nearly 80 species of reptilian prey have been recorded in the diet at this point.[5][78][79] Most predation is on snakes, with more than 40 species known in the prey spectrum. The most often found reptilian species in the diet (and sixth overall in 27 North American dietary studies) was the gopher snake (Pituophis catenifer). Red-tails are efficient predators of these large snakes, which average about 532 g (1.173 lb) in adults, although they also take many small and young gopher snakes.[82][115][174][175][176] Along the Columbia River in Washington, large colubrid snakes were found to be the primary prey, with the eastern racer (Coluber constrictor), which averages about 556 g (1.226 lb) in mature adults, the most often recorded at 21.3% of 150 prey items, followed by the gopher snake at 18%. This riverine region lacks ground squirrels and has low numbers of leporids. 43.2% of the overall diet here was made up of reptiles, while mammals, made up 40.6%.[174][177] In the Snake River NCA, the gopher snake was the second most regularly recorded (16.2% of 382 items) prey species over the course of the years, and did not appear to be subject to the extreme population fluctuations of mammalian prey here.[82] Good numbers of smaller colubrids can be taken as well, especially garter snakes.[78][84][102] Red-tailed hawks may engage in avoidance behavior to some extent with regard to venomous snakes. For example, on the San Joaquin Experimental Range in California, they were recorded taking 225 gopher snakes against 83 western rattlesnakes (Crotalus oreganus). Based on surveys, however, the rattlesnakes were five times more abundant on the range than the gopher snakes.[5][112] Nonetheless, at least 15 venomous snakes have been recorded in the red-tailed hawk’s diet.[78][79] The smallest known snake known to be hunted by red-tailed hawks is the 6 g (0.21 oz) redbelly snake (Storeria occipitomaculata).[178] Red-tailed hawks have been seen flying off with snake prey that may exceed 153 cm (5 ft 0 in) in length in some cases.[9] One red-tail was photographed killing a “fairly large” eastern diamondback rattlesnake (Crotalus adamanteus), this being North America’s heaviest snake and the heaviest venomous snake in the Americas at a large mature size of about 2,300 g (5.1 lb).[21][179] For the eastern indigo snakes (Drymarchon couperi), North America’s longest native snake, usually young and small ones are at risk.[180]

In North America, fewer lizards are typically recorded in the foods of red-tailed hawk than are snakes, probably because snakes are considerably better adapted to cooler, seasonal weather, with an extensive diversity of lizards found only in the southernmost reaches of the contiguous United States. A fair number of lizards were recorded in the diet in southern California and red-tails can be counted among the primary predatory threats to largish lizards in the United States such as the 245 g (8.6 oz) common chuckawalla (Sauromalus ater).[79][112][181][182] However, the red-tailed hawks ranging into the neotropics regularly take numerous species of lizards. This is especially true of hawks living on islands which are not naturally colonized by small mammals. Insular red-tails commonly pluck up mostly tiny anoles, that may average only 1.75 to 43.5 g (0.062 to 1.534 oz) in adult mass, depending on species.[9][93][183] Not all tropical lizards taken by red-tailed hawks are so dainty and some are easily as large as most birds and reptiles taken elsewhere such as adults of the 1,800 g (4.0 lb) San Esteban chuckwalla (Sauromalus varius) and even those as large as 2,800 g (6.2 lb) Cape spinytail iguanas (Ctenosaura hemilopha) and 4,000 g (8.8 lb) green iguanas (Iguana iguana) (though it is not clearly noted whether they can take healthy adults iguanas or not).[184][185][186] Beyond snakes and lizards, there are a few cases of red-tailed hawks preying on baby or juvenile turtles, i.e. the gopher tortoise (Gopherus polyphemus), the desert tortoise (Gopherus agassizii) and the common snapping turtle (Chelydra serpentina).[136][187]

Other prey

Records of predation on amphibians is fairly infrequent. It is thought that such prey may be slightly underrepresented, as they are often consumed whole and may not leave a trace in pellets. Their fine bones may dissolve upon consumption.[5][78][173] So far as is known, North American red-tailed hawks have preyed upon 9 species of amphibian, four of which are toads. Known amphibian prey has ranged to as small as the 0.75 g (0.026 oz) red-backed salamander (Plethodon cinereus), the smallest known vertebrate prey for red-tailed hawks, to the 430 g (15 oz) American bullfrog (Lithobates catesbeianus).[119][136][188] Invertebrates, mostly represented by insects like beetles and crickets, are better represented in the stomach contents of red-tailed hawks than their pellets or prey remains.[5][173] It is possible some invertebrate prey is ingested incidentally, as in other various birds of prey, they can in some cases be actually from the stomachs of birds eaten by the raptor.[2][5] However, some red-tails, especially immatures early in their hunting efforts, often do spend much of the day on the ground grabbing terrestrial insects and spiders.[5][78][173][189][190] The red-tailed hawks of Puerto Rico frequently consume Puerto Rican freshwater crabs (Epilobocera sinuatifrons), which average 9.4 g (0.33 oz).[9][93][191] Other island populations, such as those on Socorro island, also feed often on terrestrial crabs, here often blunting their claws while catching them.[15] Fish are the rarest class of prey based on dietary studies. Among the rare instances of them capturing fish have included captures of wild channel catfish (Ictalurus punctatus), non-native common carp (Cyprinus carpio) and ornamental koi (Cyprinus rubrofuscus) as well some hawks that were seen scavenging on dead chum salmon (Oncorhynchus keta).[79][192][193]

Interspecies predatory relationships