Columbidae

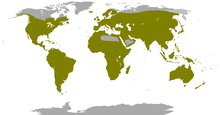

Columbidae is a bird family consisting of pigeons and doves. It is the only family in the order Columbiformes. These are stout-bodied birds with short necks, and short slender bills that in some species feature fleshy ceres. They primarily feed on seeds, fruits, and plants. The family occurs worldwide, but the greatest variety is in the Indomalayan and Australasian realms.

| Pigeon | |

|---|---|

| |

| Pink-necked green pigeon | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Clade: | Columbimorphae |

| Order: | Columbiformes Latham, 1790 |

| Family: | Columbidae Leach, 1820 |

| Subfamilies | |

|

See text | |

| |

| Geographic range of the family Columbidae | |

The family contains 344 species divided into 50 genera. Thirteen of the species are extinct.[2]

In English, the smaller species tend to be called "doves" and the larger ones "pigeons".[3] The distinction is not consistent, however,[3] and does not exist in most other languages. For example, the woodpigeon is often referred to, by another name, as the ringdove, due to the white markings on its neck. Historically, the common names for these birds involve a great deal of variation between the terms. The bird most commonly referred to as just "pigeon" is the domestic pigeon, which is common in many cities as the feral pigeon.

Pigeon is a French word that derives from the Latin pipio, for a "peeping" chick,[4] while dove is a Germanic word that refers to the bird's diving flight.[5] The English dialectal word "culver" appears to derive from Latin columba.[4] A group of doves is called a "dule," (pronounced 'dool') taken from the French word deuil (mourning).[6]

Doves and pigeons build relatively flimsy nests, often using sticks and other debris, which may be placed on branches of trees, on ledges, or on the ground, depending on species. They lay one or (usually) two white eggs at a time, and both parents care for the young, which leave the nest after 25–32 days. Unfledged baby doves and pigeons are called squabs and are generally able to fly by 5 weeks of age. These fledglings, with their immature squeaking voices, are called squeakers once they are weaned or weaning.[7] Unlike most birds, both sexes of doves and pigeons produce "crop milk" to feed to their young, secreted by a sloughing of fluid-filled cells from the lining of the crop.

Taxonomy and systematics

The name Columbidae for the family was introduced by the English zoologist William Elford Leach in a guide to the contents of the British Museum published in 1820.[8][9] Columbidae is the only living family in the order Columbiformes. The sandgrouses (Pteroclidae) were formerly placed here, but were moved to a separate order Pterocliformes based on anatomical differences (e.g., they are unable to drink by "sucking" or "pumping");[10] they are now considered to be more closely related to shorebirds.[11] Recent phylogenomic studies support the grouping of pigeons and sandgrouse together, along with mesites, forming the sister taxon to Mirandornithes.[12][13][14][15]

The Columbidae are usually divided into five subfamilies, probably inaccurately.[16] For example, the American ground and quail doves (Geotrygon), which are usually placed in the Columbinae, seem to be two distinct subfamilies.[17] The order presented here follows Baptista et al. (1997),[18] with some updates.[19][20][21]

The arrangement of genera and naming of subfamilies is in some cases provisional because analyses of different DNA sequences yield results that differ, often radically, in the placement of certain (mainly Indo-Australian) genera. This ambiguity, probably caused by long branch attraction, seems to confirm the first pigeons evolved in the Australasian region, and that the "Treronidae" and allied forms (crowned and pheasant pigeons, for example) represent the earliest radiation of the group.

The family Columbidae previously also contained the family Raphidae, consisting of the extinct Rodrigues solitaire and the dodo.[21][22][23] These species are in all likelihood part of the Indo-Australian radiation that produced the three small subfamilies mentioned above,[24] with the fruit doves and pigeons (including the Nicobar pigeon). Therefore, they are here included as a subfamily Raphinae, pending better material evidence of their exact relationships.[25]

Exacerbating these issues, columbids are not well represented in the fossil record.[26] No truly primitive forms have been found to date. The genus Gerandia has been described from Early Miocene deposits in France, but while it was long believed to be a pigeon,[27] it is now considered a sandgrouse.[28] Fragmentary remains of a probably "ptilinopine" Early Miocene pigeon were found in the Bannockburn Formation of New Zealand and described as Rupephaps;[28] "Columbina" prattae from roughly contemporary deposits of Florida is nowadays tentatively separated in Arenicolumba, but its distinction from Columbina/Scardafella and related genera needs to be more firmly established (e.g. by cladistic analysis).[29] Apart from that, all other fossils belong to extant genera.[30]

Taxonomy

Taxonomy based on the work by John H. Boyd, III,[31] a professor of economics.[32]

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Description

Size and appearance

Pigeons and doves exhibit considerable variation in size, ranging in length from 15 to 75 centimetres (5.9 to 29.5 in), and in weight from 30 g (0.066 lb) to above 2,000 g (4.4 lb).[33] The largest species is the crowned pigeon of New Guinea,[34] which is nearly turkey-sized, at a weight of 2–4 kg (4.4–8.8 lb).[35] The smallest is the New World ground dove of the genus Columbina, which is the same size as a house sparrow, weighing as little as 22 g (0.049 lb).[18] The dwarf fruit dove, which may measure as little as 13 cm (5.1 in), has a marginally smaller total length than any other species from this family.[18] One of the largest arboreal species, the Marquesan imperial pigeon, currently battles extinction.[36]

Anatomy and physiology

Overall, the anatomy of Columbidae is characterized by short legs, short bills with a fleshy cere, and small heads on large, compact bodies.[37] Like some other birds, the Columbidae have no gall bladders.[38] Some medieval naturalists concluded they have no bile (gall), which in the medieval theory of the four humours explained the allegedly sweet disposition of doves.[39] In fact, however, they do have bile (as Aristotle had earlier realized), which is secreted directly into the gut.[40]

.jpg)

The wings are large, and have eleven primary feathers;[41] pigeons have strong wing muscles (wing muscles comprise 31–44% of their body weight[42]) and are among the strongest fliers of all birds.[41]

In a series of experiments in 1975 by Dr. Mark B. Friedman, using doves, their characteristic head bobbing was shown to be due to their natural desire to keep their vision constant.[43] It was shown yet again in a 1978 experiment by Dr. Barrie J. Frost, in which pigeons were placed on treadmills; it was observed that they did not bob their heads, as their surroundings were constant.[44]

Feathers

Columbidae have unique body feathers, with the shaft being generally broad, strong, and flattened, tapering to a fine point, abruptly.[41] In general, the aftershaft is absent; however, small ones on some tail and wing feathers may be present .[45] Body feathers have very dense, fluffy bases, are attached loosely into the skin, and drop out easily.[46] Possibly serving as a predator avoidance mechanism,[47] large numbers of feathers fall out in the attacker's mouth if the bird is snatched, facilitating the bird's escape. The plumage of the family is variable.[48] Granivorous species tend to have dull plumage, with a few exceptions, whereas the frugivorous species have brightly coloured plumage.[18] The Ptilinopus (fruit doves) are some of the brightest coloured pigeons, with the three endemic species of Fiji and the Indian Ocean Alectroenas being the brightest. Pigeons and doves may be sexually monochromatic or dichromatic.[49] In addition to bright colours, pigeons may sport crests or other ornamentation.[50]

Flight

Columbidae are excellent fliers due to the lift provided by their large wings, which results in low wing loading;[51] They are highly maneuverable in flight[52] and have a low aspect ratio due to the width of their wings, allowing for quick flight launches and ability to escape from predators, but at a high energy cost.[53]

Distribution and habitat

Pigeons and doves are distributed everywhere on Earth, except for the driest areas of the Sahara Desert, Antarctica and its surrounding islands, and the high Arctic.[33] They have colonised most of the world's oceanic islands, reaching eastern Polynesia and the Chatham Islands in the Pacific, Mauritius, the Seychelles and Réunion in the Indian Ocean, and the Azores in the Atlantic Ocean.

The family has adapted to most of the habitats available on the planet. These species may be arboreal, terrestrial, or semi-terrestrial. Various species also inhabit savanna, grassland, desert, temperate woodland and forest, mangrove forest, and even the barren sands and gravels of atolls.[54]

Some species have large natural ranges. The eared dove ranges across the entirety of South America from Colombia to Tierra del Fuego,[55] the Eurasian collared dove has a massive (if discontinuous) distribution from Britain across Europe, the Middle East, India, Pakistan and China,[56] and the laughing dove across most of sub-Saharan Africa, as well as India, Pakistan, and the Middle East.[57] Other species have tiny, restricted distributions; this is most common in island endemics. The whistling dove is endemic to the tiny Kadavu Island in Fiji,[58] the Caroline ground dove is restricted to two islands, Truk and Pohnpei in the Caroline Islands,[59] and the Grenada dove is restricted to Grenada in the Caribbean.[60] Some continental species also have tiny distributions; for example, the black-banded fruit dove is restricted to a small area of the Arnhem Land of Australia,[61] the Somali pigeon is restricted to a tiny area of northern Somalia,[62] and Moreno's ground dove is restricted to the area around Salta and Tucuman in northern Argentina.[18]

The largest range of any species is that of the rock dove.[63] This species had a large natural distribution from Britain and Ireland to northern Africa, across Europe, Arabia, Central Asia, India, the Himalayas and up into China and Mongolia.[63] The range of the species increased dramatically upon domestication, as the species went feral in cities around the world.[63] The species is currently resident across most of North America, and has established itself in cities and urban areas in South America, sub-Saharan Africa, Southeast Asia, Japan, Australia, and New Zealand.[63] The species is not the only pigeon to have increased its range due to the actions of man; several other species have become established outside of their natural range after escaping captivity, and other species have increased their natural ranges due to habitat changes caused by human activity.[18] A 2020 study found that the East Coast of the U.S. includes two pigeon genetic megacities, in New York and Boston, and they don't mix.[64]

Behaviour

Male pigeons are more opportunistic to mate with another female.[65]

Feeding

Seeds and fruit form the major component of the diets of pigeons and doves.[33][66] In fact, the family can be divided into the seed-eating or granivorous species (subfamily Columbinae) and the fruit-and-mast-eating or frugivorous species (the other four subfamilies).[67] The granivorous species typically feed on seed found on the ground, whereas the frugivorous species tend to feed in trees.[67] There are morphological adaptations that can be used to distinguish between the two groups: granivores tend to have thick walls in their gizzards, intestines, and esophagi whereas the frugivores tend to have thin walls.[33] In addition, fruit-eating species have short intestines whereas those that eat seeds have longer ones.[68] Frugivores are capable of clinging to branches and even hang upside down to reach fruit.[18][67]

In addition to fruit and seeds, a number of other food items are taken by many species. Some, particularly the ground doves and quail-doves, eat a large number of prey items such as insects and worms.[67] One species, the atoll fruit dove, is specialised in taking insect and reptile prey.[67] Snails, moths, and other insects are taken by white-crowned pigeons, orange fruit doves, and ruddy ground doves.[18]

Status and conservation

While many species of pigeons and doves have benefited from human activities and have increased their ranges, many other species have declined in numbers and some have become threatened or even succumbed to extinction.[69] Among the ten species to have become extinct since 1600 (the conventional date for estimating modern extinctions) are two of the most famous extinct species, the dodo and the passenger pigeon.[69]

The passenger pigeon was exceptional for a number of reasons. In modern times, it is the only pigeon species that was not an island species to have become extinct[69] even though it was once the most numerous species of bird on Earth. Its former numbers are difficult to estimate, but one ornithologist, Alexander Wilson, estimated one flock he observed contained over two billion birds.[70] The decline of the species was abrupt; in 1871, a breeding colony was estimated to contain over a hundred million birds, yet the last individual in the species was dead by 1914.[71] Although habitat loss was a contributing factor, the species is thought to have been massively over-hunted, being used as food for slaves and, later, the poor, in the United States throughout the 19th century.

The dodo, and its extinction, was more typical of the extinctions of pigeons in the past. Like many species that colonise remote islands with few predators, it lost much of its predator avoidance behaviour, along with its ability to fly.[72] The arrival of people, along with a suite of other introduced species such as rats, pigs, and cats, quickly spelled the end for this species and all the other island forms that have become extinct.[72]

Around 59 species of pigeons and doves are threatened with extinction today, about 19% of all species.[73] Most of these are tropical and live on islands. All of the species are threatened by introduced predators, habitat loss, hunting, or a combination of these factors.[72] In some cases, they may be extinct in the wild, as is the Socorro dove of Socorro Island, Mexico, last seen in the wild in 1972, driven to extinction by habitat loss and introduced feral cats.[74] In some areas, a lack of knowledge means the true status of a species is unknown; the Negros fruit dove has not been seen since 1953,[75] and may or may not be extinct, and the Polynesian ground dove is classified as critically endangered, as whether it survives or not on remote islands in the far west of the Pacific Ocean is unknown.[76]

Various conservation techniques are employed to prevent these extinctions, including laws and regulations to control hunting pressure, the establishment of protected areas to prevent further habitat loss, the establishment of captive populations for reintroduction back into the wild (ex situ conservation), and the translocation of individuals to suitable habitats to create additional populations.[72][77]

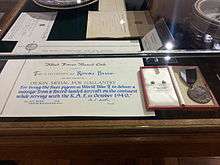

Military

The pigeon was used in both World War I and II, notably by the Australian, French, German, American, and UK forces. They were also awarded with various laurels throughout, for their service. On 2 December 1943, three pigeons – Winkie, Tyke, and White Vision – were awarded the first Dickin medal, serving with Britain's Royal Air Force, for rescuing an air force crew during World War II.[78] Thirty-two pigeons have been decorated with the Dickin Medal, citing them for "brave service",[79] for war contributions, including Commando, G.I. Joe,[80] Paddy, Royal Blue, and William of Orange.[81]

Cher Ami, a homing pigeon in World War I, was awarded the Croix de Guerre Medal, by France, with a palm Oak Leaf Cluster for her service in Verdun.[82] Despite having almost lost a leg and being shot in the chest, she managed to travel around twenty-five miles to deliver the message that saved 194 men of the Lost Battalion of the 77th Infantry Division in the Battle of the Argonne, in October 1918.[82][78] When Cher Ami died, she was mounted and is part of the permanent exhibit at the National Museum of American History of the Smithsonian Institution.[83]

A grand ceremony was held in Buckingham Palace to commemorate a platoon of pigeons that braved the battlefields of Normandy to deliver vital plans to Allied forces on the fringes of Germany.[84] Three of the actual birds that received the medals are on show in the London Military Museum so that well-wishers can pay their respects.[84]

Domestication

The rock pigeon has been domesticated for hundreds of years.[85] It has been bred into several varieties kept by hobbyists, of which the best known is the homing pigeon or racing homer.[85] Other popular breeds are tumbling pigeons such as the Birmingham roller, and fancy varieties that are bred for certain physical characteristics such as large feathers on the feet or fan-shaped tails. Domesticated rock pigeons are also bred as carrier pigeons,[50] used for thousands of years to carry brief written messages,[86] and release doves used in ceremonies.[87] White doves are also commonly used in magic acts.[88]

In religion

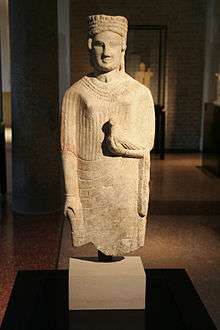

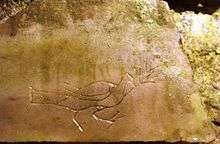

In ancient Mesopotamia, doves were prominent animal symbols of Inanna-Ishtar, the goddess of love, sexuality, and war.[89][90] Doves are shown on cultic objects associated with Inanna as early as the beginning of the third millennium BC.[89] Lead dove figurines were discovered in the temple of Ishtar at Aššur, dating to the thirteenth century BC,[89] and a painted fresco from Mari, Syria, shows a giant dove emerging from a palm tree in the temple of Ishtar,[90] indicating that the goddess herself was sometimes believed to take the form of a dove.[90] In the Epic of Gilgamesh, Utnapishtim releases a dove and a raven to find land; the dove merely circles and returns.[91] Only then does Utnapishtim send forth the raven, which does not return, and Utnapishtim concludes the raven has found land.[91]

In the ancient Levant, doves were used as symbols for the Canaanite mother goddess Asherah.[89][90][92] The ancient Greek word for "dove" was peristerá,[89][90] which may be derived from the Semitic phrase peraḥ Ištar, meaning "bird of Ishtar".[89] In classical antiquity, doves were sacred to the Greek goddess Aphrodite,[93][94][89][90] who absorbed this association with doves from Inanna-Ishtar.[90] Aphrodite frequently appears with doves in ancient Greek pottery.[93] The temple of Aphrodite Pandemos on the southwest slope of the Athenian Acropolis was decorated with relief sculptures of doves with knotted fillets in their beaks[93] and votive offerings of small, white, marble doves were discovered in the temple of Aphrodite at Daphni.[93] During Aphrodite's main festival, the Aphrodisia, her altars would be purified with the blood of a sacrificed dove.[95] Aphrodite's associations with doves influenced the Roman goddesses Venus and Fortuna, causing them to become associated with doves as well.[92]

In the Hebrew Bible, doves or young pigeons are acceptable burnt offerings for those who cannot afford a more expensive animal.[96] In Genesis, Noah sends a dove out of the ark, but it came back to him because the floodwaters had not receded. Seven days later, he sent it again and it came back with an olive branch in her mouth, indicating the waters had receded enough for an olive tree to grow. "Dove" is also a term of endearment in the Song of Songs and elsewhere. In Hebrew, Jonah (יוֹנָה) means dove.[97] The "sign of Jonas" in is related to the "sign of the dove".[98]

Jesus's parents sacrificed doves on his behalf after his circumcision (Luke).[98] Later, the Holy Spirit descended upon Jesus at his baptism like a dove (Matthew), and subsequently the "peace dove" became a common Christian symbol of the Holy Spirit.[98]

In Islam, doves and the pigeon family in general are respected and favoured because they are believed to have assisted the final prophet of Islam, Muhammad, in distracting his enemies outside the cave of Thaw'r, in the great Hijra.[99] A pair of pigeons had built a nest and laid eggs at once, and a spider had woven cobwebs, which in the darkness of the night made the fugitives believe that Muhammad could not be in that cave.[99]

As food

Several species of pigeons and doves are used as food; however, all types are edible.[100] Domesticated or hunted pigeons have been used as the source of food since the times of the Ancient Middle East, Ancient Rome, and Medieval Europe.[79] It is familiar meat within Jewish, Arab, and French cuisines. According to the Tanakh, doves are kosher, and they are the only birds that may be used for a korban. Other kosher birds may be eaten, but not brought as a korban. Pigeon is also used in Asian cuisines, such as Chinese, Assamese, and Indonesian cuisines.

In Europe, the wood pigeon is commonly shot as a game bird,[101] while rock pigeons were originally domesticated as a food species, and many breeds were developed for their meat-bearing qualities.[54] The extinction of the passenger pigeon in North America was at least partly due to shooting for use as food.[102] Mrs Beeton's Book of Household Management contains recipes for roast pigeon and pigeon pie, a popular, inexpensive food in Victorian industrial Britain.[103]

See also

- Doves as symbols

- Gamasoidosis

- Homing pigeon

- List of Columbidae species

- Marquesan imperial pigeon

- Pigeon control

- War pigeon

References

- Farner, Donald (2012). Avian Biology. Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-323-15799-5.

- Gill, Frank; Donsker, David; Rasmussen, Pamela, eds. (2020). "Pigeons". IOC World Bird List Version 10.1. International Ornithologists' Union. Retrieved 27 February 2020.

- McDonald, Hannah (17 August 2008). "What's the Difference Between Pigeons and Doves?". Big Questions. Mental Floss.

- Harper, Douglas. "pigeon". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- Harper, Douglas. "dove". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- Lipton, James (1991). An Exaltation of Larks. Viking. ISBN 978-0-670-30044-0.

- Crome, Francis H.J. (1991). Forshaw, Joseph (ed.). Encyclopaedia of Animals: Birds. London: Merehurst Press. pp. 115–116. ISBN 978-1-85391-186-6.

- Leach, William Elford (1820). "Eleventh Room". Synopsis of the Contents of the British Museum (17th ed.). London: British Museum. p. 68. Although the name of the author is not specified in the document, Leach was the Keeper of Zoology at the time.

- Bock, Walter J. (1994). History and Nomenclature of Avian Family-Group Names. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. Number 222. New York: American Museum of Natural History. p. 139. hdl:2246/830.

- Cade, Tom J.; Willoughby, Ernest J.; MacLean, Gordon L. (1966). "Drinking Behavior of Sandgrouse in the Namib and Kalahari Deserts, Africa" (PDF). The Auk. 83 (1): 124–126. doi:10.2307/4082983. JSTOR 4082983.

- "Columbiformes (Pigeons, Doves and Dodos)". Francis Hugh John Crome. Grzimek's Animal Life Encyclopedia. Michael Hutchins, Dennis A. Thoney, and Melissa C. McDade (eds.). Vol. 9: Birds II. 2nd ed. Detroit: Gale, 2004. pp. 241–246.

- Jarvis, E. D.; Mirarab, S; Aberer, A. J.; Li, B; Houde, P; Li, C; Ho, S. Y.; Faircloth, B. C.; Nabholz, B; Howard, J. T.; Suh, A; Weber, C. C.; Da Fonseca, R. R.; Li, J; Zhang, F; Li, H; Zhou, L; Narula, N; Liu, L; Ganapathy, G; Boussau, B; Bayzid, M. S.; Zavidovych, V; Subramanian, S; Gabaldón, T; Capella-Gutiérrez, S; Huerta-Cepas, J; Rekepalli, B; Munch, K; et al. (2014). "Whole-genome analyses resolve early branches in the tree of life of modern birds". Science. 346 (6215): 1320–31. Bibcode:2014Sci...346.1320J. doi:10.1126/science.1253451. PMC 4405904. PMID 25504713.

- Fain, Matthew G.; Houde, Peter (2004). "Parallel radiations in the primary clades of birds". Evolution. 58 (11): 2558–2573. doi:10.1554/04-235. PMID 15612298.

- Hackett, Shannon J.; et al. (2008). "A Phylogenomic Study of Birds Reveals Their Evolutionary History". Science. 320 (5884): 1763–1768. Bibcode:2008Sci...320.1763H. doi:10.1126/science.1157704. PMID 18583609. S2CID 6472805.

- Yuri, T.; et al. (2013). "Parsimony and Model-Based Analyses of Indels in Avian Nuclear Genes Reveal Congruent and Incongruent Phylogenetic Signals". Biology. 2 (1): 419–444. doi:10.3390/biology2010419. PMC 4009869. PMID 24832669.

- Allen, Barbara (2009). Pigeon. Reaktion Books. ISBN 978-1-86189-711-4.

- Basically, the conventional treatment had two large subfamilies, one for the fruit doves, imperial pigeons, and fruit pigeons, and another for nearly all of the remaining species. Additionally, three monotypic subfamilies were noted, one each for the genera Goura, Otidiphaps, and Didunculus. The old subfamily Columbinae consists of five distinct lineages, whereas the other four groups are more or less accurate representations of the evolutionary relationships.

- Baptista, L. F.; Trail, P. W.; Horblit, H. M. (1997). "Family Columbidae (Doves and Pigeons)". In del Hoyo, J.; Elliott, A.; Sargatal, J. (eds.). Handbook of birds of the world. 4: Sandgrouse to Cuckoos. Barcelona: Lynx Edicions. ISBN 978-84-87334-22-1.

- Johnson, Kevin P.; Clayton, Dale H. (2000). "Nuclear and Mitochondrial Genes Contain Similar Phylogenetic. Signal for Pigeons and Doves (Aves: Columbiformes)" (PDF). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 14 (1): 141–151. doi:10.1006/mpev.1999.0682. PMID 10631048.

- Johnson, Kevin P.; de Kort, Selvino; Dinwoodey, Karen, Mateman, A. C.; ten Cate, Carel; Lessells, C. M. & Clayton, Dale H. (2001). "A molecular phylogeny of the dove genera Streptopelia and Columba" (PDF). Auk. 118 (4): 874–887. doi:10.1642/0004-8038(2001)118[0874:AMPOTD]2.0.CO;2. hdl:20.500.11755/a92515bb-c1c6-4c0e-ae9a-849936c41ca2. JSTOR 4089839.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Shapiro, Beth; Sibthorpe, Dean; Rambaut, Andrew; Austin, Jeremy; Wragg, Graham M.; Bininda-Emonds, Olaf R. P.; Lee, Patricia L. M.; Cooper, Alan (2002). "Flight of the Dodo". Science. 295 (5560): 1683. doi:10.1126/science.295.5560.1683. PMID 11872833. S2CID 29245617. Supplementary information

- Janoo, Anwar (2005). "Discovery of isolated dodo bones Raphus cucullatus (L.), Aves, Columbiformes from Mauritius cave shelters highlights human predation, with a comment on the status of the family Raphidae Wetmore, 1930". Annales de Paléontologie. 91 (2): 167. doi:10.1016/j.annpal.2004.12.002.

- Cheke, Anthony; Hume, Julian P. (2010). Lost Land of the Dodo: The Ecological History of Mauritius, Réunion and Rodrigues. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4081-3305-7.

- "dodo | extinct bird". Encyclopedia Britannica.

- Christidis, Les; Boles, Walter E. (2008). Systematics and Taxonomy of Australian Birds. Csiro Publishing. ISBN 978-0-643-09964-7.

- Fountaine, Toby M. R.; Benton, Michael J.; Dyke, Gareth J.; Nudds, Robert L. (2005). "The quality of the fossil record of Mesozoic birds". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 272 (1560): 289–294. doi:10.1098/rspb.2004.2923. PMC 1634967. PMID 15705554.

- Olson, Storrs L. (1985). "The fossil record of birds". In Farmer, Donald S.; King, James R.; Parkes, Kenneth C. (eds.). Avian Biology, Vol. VIII. Academic Press. pp. 79–238. hdl:10088/6553. ISBN 978-0-12-249408-6.

The earliest dove yet known, from the early Miocene (Aquitanian) of France, was a small species named Columba calcaria by Milne-Edwards (1867–1871) from a single humerus, for which Lambrecht (1933) later created the genus Gerandia

- Worthy, Trevor H.; Hand, Suzanne J.; Worthy, Jennifer P.; Tennyson, Alan J. D.; Scofield, R. Paul (2009). "A large fruit pigeon (Columbidae) from the Early Miocene of New Zealand". The Auk. 126 (3): 649–656. doi:10.1525/auk.2009.08244.

Because Columba calcaria Milne-Edwards, 1867–1871, from the Lower Miocene at Saint-Gérand-le-Puy in France, is now also considered a sandgrouse, as Gerandia calcaria (Mlíkovský 2002), there is no pre-Pliocene columbid record in Europe.

- "Fossilworks: Gateway to the Paleobiology Database". fossilworks.org.

- Mayr, Gerald (2009). Paleogene Fossil Birds. Springer. ISBN 978-3-540-89628-9.

- Boyd, John H., III (2007). "COLUMBEA: Mirandornithes, Columbimorphae". JBoyd.net. Retrieved 30 December 2015.

- Boyd, John H., III. "John Boyd's Home Page". JBoyd.net. Retrieved 11 January 2017.

- "Columbidae (doves and pigeons)". Animal Diversity Web.

- "Victoria crowned-pigeon videos, photos and facts – Goura victoria". Arkive. Archived from the original on 24 April 2017. Retrieved 23 April 2017.

- "Southern crowned-pigeon videos, photos and facts – Goura scheepmakeri". Arkive. Archived from the original on 24 April 2017. Retrieved 23 April 2017.

- Thorsen, M., Blanvillain, C., & Sulpice, R. (2002). Reasons for decline, conservation needs, and a translocation of the critically endangered upe (Marquesas imperial pigeon, Ducula galeata), French Polynesia. Department of Conservation.

- Smith, Paul. "COLUMBIDAE Pigeons and Doves FAUNA PARAGUAY". www.faunaparaguay.com.

- Hagey, LR; Schteingart, CD; Ton-Nu, HT; Hofmann, AF (1994). "Biliary bile acids of fruit pigeons and doves (Columbiformes)" (PDF). Journal of Lipid Research. 35 (11): 2041–8. PMID 7868982.

- "Doves". The Medieval Bestiary. Retrieved 31 January 2010.

- Browne, Thomas (1646). Pseudodoxia Epidemica. III.iii (1672 ed.). available online at University of Chicago. Retrieved 31 January 2010.

- "Columbiformes (Pigeons, Doves, and Dodos) – Dictionary definition of Columbiformes (Pigeons, Doves, and Dodos)". www.encyclopedia.com.

- Clairmont, Patsy (2014). Twirl: A Fresh Spin at Life. Harper Collins. ISBN 978-0-8499-2299-2.

- "Why do pigeons bob their heads when they walk? Everyday Mysteries: Fun Science Facts from the Library of Congress". www.loc.gov.

- Necker, R (2007). "Head-bobbing of walking birds" (PDF). Journal of Comparative Physiology A. 193 (12): 1177–83. doi:10.1007/s00359-007-0281-3. PMID 17987297.

- Schodde, Richard; Mason, I. J. (1997). Aves (Columbidae to Coraciidae). Csiro Publishing. ISBN 978-0-643-06037-1.

- Skutch, A. F. (1964). "Life Histories of Central American Pigeons" (PDF). Wilson Bulletin. 76 (3): 211.

- "DiversityofLife2012 – Pigeon". diversityoflife2012.wikispaces.com.

- Hilty, Steven L. (2002). Birds of Venezuela. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-3409-9.

- Valdez, Diego Javier; Benitez-Vieyra, Santiago Miguel (2016). "A Spectrophotometric Study of Plumage Color in the Eared Dove (Zenaida auriculata), the Most Abundant South American Columbiforme". PLOS ONE. 11 (5): e0155501. Bibcode:2016PLoSO..1155501V. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0155501. PMC 4877085. PMID 27213273.

- "Pigeon family Columbidae". creagrus.home.montereybay.com.

- Alerstam, Thomas (1993). Bird Migration. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-44822-2.

- Forshaw, Joseph; Cooper, William (2015). Pigeons and Doves in Australia. Csiro Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4863-0405-9.

- Pap, Péter L.; Osváth, Gergely; Sándor, Krisztina; Vincze, Orsolya; Bărbos, Lőrinc; Marton, Attila; Nudds, Robert L.; Vágási, Csongor I. (2015). Williams, Tony (ed.). "Interspecific variation in the structural properties of flight feathers in birds indicates adaptation to flight requirements and habitat". Functional Ecology. 29 (6): 746–757. doi:10.1111/1365-2435.12419.

- "Pigeons and Doves (Columbidae) – Dictionary definition of Pigeons and Doves (Columbidae)". www.encyclopedia.com.

- "Zenaida auriculata (eared dove)". Animal Diversity Web.

- "Eurasian collared dove (Streptopelia decaocto) detail". natureconservation.in. 5 February 2019.

- "Laughing Dove This Bird Is Native To Subsaharan Africa The Middle East And India Where It Is Known As The Little Brown Dove It Inhabits Scrubland And Feeds On Grass Seeds And Grain Stock Photo". www.gettyimages.in. Archived from the original on 25 April 2017. Retrieved 24 April 2017.

- "Whistling Fruit Doves". www.beautyofbirds.com.

- Gibbs, David (2010). Pigeons and Doves: A Guide to the Pigeons and Doves of the World. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4081-3555-6.

- "Grenada Dove (Leptotila wellsi) - BirdLife species factsheet". datazone.birdlife.org.

- Schodde, Richard; Mason, I. J. (1997). Aves (Columbidae to Coraciidae). Csiro Publishing. ISBN 978-0-643-06037-1.

- "Somali Pigeon (Columba oliviae)". www.hbw.com.

- "Rock Pigeons (Columba livia) aka Feral or Domestic Pigeons". www.beautyofbirds.com.

- Sokol, Joshua (23 April 2020). "New York and Boston Pigeons Don't Mix". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- Shehzad Zareen; Hameed Ur Rehman; Raqeebullah; Abid Ur Rehman (2016). "Fidelity Analysis among Mates of Different Breeds of Columba livia, District Kohat, KPK, Pakistan" (PDF). Journal of Entomology and Zoology Studies. 4 (4): 195–197. Retrieved 20 August 2016.

- "What Do Doves Eat – Best Food For Doves". www.birdfeedersspot.com.

- "Pigeons And Doves – What's The Differance?". birdsofeden.co.za. 22 July 2011.

- Campbell, Bruce; Lack, Elizabeth (2010). A Dictionary of Birds. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4081-3838-0.

- Society, National Geographic. "Species Extinction Time Line | Animals Lost SInce 1600". National Geographic.

- "The Birds". The New Yorker. 6 January 2014.

- "Passenger Pigeon". Nebraska Bird Library.

- Gibbs, David (2010). Pigeons and Doves: A Guide to the Pigeons and Doves of the World. A&C Black. ISBN 978-1-4081-3556-3.

- Walker, J. (2007). "Geographical patterns of threat among pigeons and doves (Columbidae)". Oryx. 41 (3): 289–299. doi:10.1017/S0030605307001016.

- BirdLife International (2009). "Socorro Dove Zenaida graysoni". Data Zone. BirdLife International. Retrieved 26 June 2009.

- "Ptilinopus arcanus (Negros Fruit-dove, Negros Fruit Dove, Negros Fruit-Dove)". www.iucnredlist.org.

- "Alopecoenas erythropterus (Polynesian Ground-dove, Polynesian Ground Dove, Polynesian Ground-Dove, Society Islands Ground-dove, White-collared Ground-dove)". www.iucnredlist.org.

- Tidemann, Sonia C.; Gosler, Andrew (2012). Ethno-ornithology: "Birds, Indigenous Peoples, Culture and Society". Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-54384-5.

- "Pigeons Awarded First Dickin Medals for Bravery ⋆ History Channel". History Channel. 20 June 2016.

- Eastman, John (2000). The Eastman Guide to Birds: Natural History Accounts for 150 North American Species. Stackpole Books. ISBN 978-0-8117-4552-9.

- "See some of the 67 animals who've been handed the Dickin Medal for bravery". BBC. 5 April 2016.

- "The Dickin Medal". www.forces-war-records.co.uk.

- "Cher Ami". National Museum of American History.

- "Cher Ami "Dear Friend" WWI". Flickr. 25 September 2006. Retrieved 26 April 2008.

- "Aerial athletes". New Age Xtra. Archived from the original on 7 October 2017. Retrieved 30 April 2017.

- Shapiro, Michael D.; Domyan, Eric T. (2013). "Domestic pigeons". Current Biology. 23 (8): R302–R303. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2013.01.063. PMC 4854524. PMID 23618660.

- "WysInfo Docuwebs – The Columbidae Family". www.wysinfo.com.

- "Release of White Doves for your wedding from Pangroove Elegant Events In Barbados". www.pangroove.com. Archived from the original on 16 August 2017. Retrieved 30 April 2017.

- "White Dove". Animal World.

- Botterweck, G. Johannes; Ringgren, Helmer (1990). Theological Dictionary of the Old Testament. VI. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co. pp. 35–36. ISBN 978-0-8028-2330-4.

- Lewis, Sian; Llewellyn-Jones, Lloyd (2018). The Culture of Animals in Antiquity: A Sourcebook with Commentaries. New York City, New York and London, England: Routledge. p. 335. ISBN 978-1-315-20160-3.

- Kovacs, Maureen Gallery (1989). The Epic of Gilgamesh. Stanford University Press. p. 102. ISBN 978-0-8047-1711-3.

- Resig, Dorothy D. The Enduring Symbolism of Doves, From Ancient Icon to Biblical Mainstay" Archived 31 January 2013 at the Wayback Machine, BAR Magazine.

- Cyrino, Monica S. (2010). Aphrodite. Gods and Heroes of the Ancient World. New York City, New York and London, England: Routledge. pp. 120–123. ISBN 978-0-415-77523-6.

- Tinkle, Theresa (1996). Medieval Venuses and Cupids: Sexuality, Hermeneutics, and English Poetry. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. p. 81. ISBN 978-0804725156.

- Simon, Erika (1983). Festivals of Attica: An Archaeological Companion. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 978-0-299-09184-2.

- Freedman, David Noel; Myers, Allen C. (2000). Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible. Amsterdam University Press. ISBN 978-90-5356-503-2.

- Yonah Jonah Blue Letter Bible. Blueletterbible.org. Retrieved on 5 March 2013.

- God's Kingdom Ministries serious Bible Study Chapter 12: The Sign of Jonah. Gods-kingdom-ministries.net. Retrieved on 5 March 2013.

- "The Dawn of Prophethood". Al-Islam.org. 18 October 2012.

- Eggs. Cooking Methods & Materials, Critter Cuisine

- "TPWD: Doves and Pigeons – Introducing Birds to Young Naturalists". tpwd.texas.gov.

- "Why the Passenger Pigeon Went Extinct". Audubon. 17 April 2014.

- CHAPTER 40 – DINNERS AND DINING Mrs Beeton's Book of Household Management. Mrsbeeton.com. Retrieved on 5 March 2013.

Further reading

- Blechman, Andrew, Pigeons: The Fascinating Saga of the World's Most Revered and Reviled Bird (Grove Press 2007) ISBN 978-0-8021-4328-0

- Gibbs, Barnes and Cox, Pigeons and Doves (Pica Press 2001) ISBN 1-873403-60-7

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Doves |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Columbidae. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Columbidae |

| Look up Columbidae in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Columbidae.org.uk Conservation of pigeons and doves

- Dove videos on the Internet Bird Collection

- Dove sounds

- Pigeon Fact Sheet from the National Pest Management Association with information on habits, habitat and health threats

- "Pigeon breeds: from the NPA Standard – Table of Contents by Groups". NPAUSA.org. American National Pigeon Association. 2014.

- "British Pigeon Show Society Hall of Fame, Show Categories and Trophies". Showpigeons. British Pigeon Show Society. 2014.

- "List of the Breeds of Fancy Pigeons" (PDF). Entente Européenne d'Áviculture et de Cuniculture. 1 October 2009.