Western capercaillie

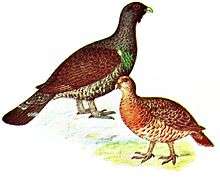

The western capercaillie (Tetrao urogallus), also known as the wood grouse, heather cock, or just capercaillie /ˌkæpərˈkeɪli/, is a member of the grouse family and its largest member. The largest known specimen, recorded in captivity, had a weight of 7.2 kilograms (16 pounds). Found across Europe and the Palearctic, this ground-living forest bird is renowned for its mating display. The species shows extreme sexual dimorphism, with the male twice the size of the female. The worldwide population is in the category "least concern" of the IUCN,[1] although the populations of Central Europe are declining and endangered, or already extinct.

| Western capercaillie | |

|---|---|

.jpg) | |

| Male (cock) | |

| |

| Female (hen) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Galliformes |

| Family: | Phasianidae |

| Genus: | Tetrao |

| Species: | T. urogallus |

| Binomial name | |

| Tetrao urogallus | |

| |

| Range of the western capercaillie[2] | |

| |

| Distribution in Europe[2] | |

Etymology

The word capercaillie is a corruption of the Scottish Gaelic capall-coille (Scottish Gaelic pronunciation: [kʰaʰpəɫ̪ˈkʰɤʎə]) "wood-horse". The Scots borrowing is spelled capercailzie (the Scots use of z represents an archaic spelling with yogh and is silent; see Mackenzie (surname)). The current spelling was standardised by William Yarrell in 1843.[3]

The genus name is derived from the Latin name of a game bird, probably the black grouse. The species name, urogallus, is a New Latin partial homophone of German Auerhuhn, "mountain cock".[4]

Taxonomy

The species was first described by Carl Linnaeus in his 1758 10th edition of Systema Naturae under its current binomial name.[5]

Its closest relative is the black-billed capercaillie, Tetrao parvirostris, which breeds in the larch taiga forests of eastern Russia and parts of northern Mongolia and China.

Subspecies

There are several subspecies, listed from west to east:[6]

- T. u. cantabricus (Cantabrian capercaillie) – Castroviejo, 1967: found in northwestern Spain

- T. u. aquitanicus Ingram, 1915: found in the Pyrenees of Spain and France

- T. u. crassirostris (syn. major) C.L. Brehm, 1831: found in Central Europe (Alps to Estonia)

- T. u. rudolfi Dombrowski, 1912: found in Southeast Europe (Bulgaria to southwest Ukraine)

- T. u. urogallus Linnaeus, 1758: found in Scandinavia and Scotland (where introduced)

- T. u. karelicus Lönnberg, 1924: found in Finland and Karelia

- T. u. lonnbergi Snigirevski, 1957: found in the Kola Peninsula

- T. u. pleskei Stegmann, 1926: found in Belarus, central European Russia

- T. u. obsoletus Snigerewski, 1937: found in northern European Russia

- T. u. volgensis Buturlin, 1907: found in southeastern European Russia

- T. u. uralensis Nazarov, 1886: found in the Urals and western Siberia

- T. u. taczanowskii Stejneger, 1885: found in Central Siberia to Altai Mountains (northwest Mongolia and east Kazakhstan)

The subspecies show increasing amounts of white on the underparts of males from west to east, almost wholly black with only a few white spots underneath in western and central Europe to nearly pure white in Siberia, where the black-billed capercaillie occurs. Variation in females is much less.

The native Scottish population, which became extinct between 1770 and 1785, was probably a distinct subspecies, though it was never formally described as such; the same is likely of the extinct Irish population.

Hybrids

Western capercaillies are known to hybridise occasionally with black grouse (these hybrids being known by the German name Rackelhahn) and the closely related black-billed capercaillie.

Description

Male and female western capercaillie can easily be differentiated by their size and colouration. The cock is much bigger than the hen. It is one of the most sexually dimorphic in size of living bird species, only exceeded by the larger types of bustards and a select few members of the pheasant family.

Cocks typically range from 74 to 85 centimetres (29 to 33 inches) in length with wingspan of 90 to 125 cm (35 to 49 in) and an average weight of 4.1 kg (9 lb 1 oz).[7][8][9] The largest wild cocks can attain a length of 100 cm (40 in) and weight of 6.7 kg (14 lb 12 oz).[10] The largest specimen recorded in captivity had a weight of 7.2 kg (15 lb 14 oz). The weight of 75 wild cocks was found to range from 3.6 to 5.05 kg (7 lb 15 oz to 11 lb 2 oz).[9] The body feathers are dark grey to dark brown, while the breast feathers are dark metallic green. The belly and undertail coverts vary from black to white depending on race (see below).

The hen is much smaller, weighing about half as much as the cock. The capercaillie hen's body from beak to tail is approximately 54–64 cm (21–25 in) long, the wingspan is 70 cm (28 in) and weighs 1.5–2.5 kg (3 lb 5 oz–5 lb 8 oz), with an average of 1.8 kg (3 lb 15 oz).[9] Feathers on the upper parts are brown with black and silver barring; on the underside they are more light and buffish yellow.

Both sexes have a white spot on the wing bow. They have feathered legs, especially in the cold season, for protection against cold. Their toe rows of small, elongated horn tacks provide a snowshoe effect that led to the German family name "Rauhfußhühner", literally translated as "rough feet chickens".

These so-called "courting tacks" make a clear track in the snow. The sexes can be distinguished very easily by the size of their footprints.

There is a bright red spot of naked skin above each eye. In German hunters' language, these are the so-called "roses".

The small chicks resemble the hen in their cryptic colouration, which is a passive protection against predators. Additionally, they wear black crown feathers. At an age of about three months, in late summer, they moult gradually towards the adult plumage of cocks and hens. The eggs are about the same size and form as chicken eggs, but are more speckled with brown spots.

Distribution and habitat

The capercaillie is a non-migratory sedentary species, breeding across northern parts of Europe and the Palearctic in mature conifer forests with diverse species composition and a relatively open canopy structure.

At one time it could be found in all the taiga forests of the Palearctic in the cold temperate latitudes and the coniferous forest belt in the mountain ranges of warm temperate Europe. The Scottish population became extinct, but has been reintroduced from the Swedish population; in Germany it is on the "Red List" as a species threatened by extinction and is no longer found in the lower mountainous areas of Bavaria; in the Bavarian Forest, the Black Forest and the Harz mountains numbers of surviving western capercaillie decline even under massive efforts to breed them in captivity and release them into the wild. In Switzerland, they are found in the Swiss Alps and in the Jura; they are also present in the Austrian and Italian Alps. The species is extinct in Belgium. In Ireland it was common until the 17th century, but died out in the 18th. In Norway, Sweden, Finland, Russia and Romania populations are large, and it is a common bird to see in forested regions.

The most serious threats to the species are habitat degradation, particularly conversion of diverse native forest into often single-species timber plantations, and to birds colliding with fences erected to keep deer out of young plantations. Increased numbers of small predators that prey on capercaillies (e.g., red fox) due to the loss of large predators who control smaller carnivores (e.g., gray wolf, brown bear) cause problems in some areas.

Status and conservation

This species has an estimated range of 1,000,000–10,000,000 km2 (390,000–3,860,000 sq mi) and a population of between 1.5 and 2 million individuals in Europe alone. There is some evidence of a population decline, but the overall species is not believed to approach the IUCN Red List threshold of a population decline of more than 30% in ten years or three generations. It is therefore evaluated as least concern.[1]

As reported by the Spanish researcher Félix Rodríguez de la Fuente in his "Fauna" series, the northwestern Spanish subspecies T. u. cantabricus—an Ice Age remnant—was threatened in the 1960s by commercial gathering of holly fruit-bearing branches for sale as Christmas ornaments—a practice imported from Anglo-Saxon or Germanic countries.

In Scotland, the population has declined greatly since the 1960s because of deer fencing, predation and lack of suitable habitat (Caledonian Forest). The population plummeted from a high of 10,000 pairs in the 1960s to fewer than 1000 birds in 1999. It was even named as the bird most likely to become extinct in the UK by 2015.

In mountainous skiing areas, poorly marked cables for ski-lifts have contributed to mortality. Their effects can be mitigated by proper coloring, sighting and height alterations.

Behaviour and ecology

The western capercaillie is adapted to its original habitats—old coniferous forests with a rich interior structure and dense ground vegetation of Vaccinium species under a light canopy. They mainly feed on Vaccinium species, especially bilberry, find cover in young tree growth, and use the open spaces when flying. As habitat specialists, they hardly use any other forest types.

Western capercaillies are not elegant fliers due to their body weight and short, rounded wings. While taking off they produce a sudden thundering noise that deters predators. Because of their body size and wingspan they avoid young and dense forests when flying. While flying they rest in short gliding phases. Their feathers produce a whistling sound.

Western capercaillie, especially the hens with young chicks, require resources that should occur as parts of a small-scaled patchy mosaic: These are food plants, small insects for the chicks, cover in dense young trees or high ground vegetation, old trees with horizontal branches for sleeping. These criteria are met best in old forest stands with spruce and pine, dense ground vegetation and local tree regrowth on dry slopes in southern to western expositions. These open stands allow flights downslope, and the tree regrowth offers cover.

In the lowlands such forest structures developed over centuries by heavy exploitation, especially by the use of litter and grazing livestock. In the highlands and along the ridges of mountain areas in temperate Europe as well as in the taiga region from Fennoscandia to Siberia, the boreal forests show this open structure due to the harsh climate, offering optimal habitats for capercaillie without human influence. Dense and young forests are avoided as there is neither cover nor food, and flight of these large birds is greatly impaired.

The abundance of western capercaillie depends—as with most species—on habitat quality. It is highest in sun-flooded open, old mixed forests with spruce, pine, fir and some beech with a rich ground cover of Vaccinium species.

Spring territories are about 25 hectares (62 acres) per bird. Comparable abundances are found in taiga forests. Thus, the western capercaillie never had particularly high densities, despite the legends that hunters may speculate about. Adult cocks are strongly territorial and occupy a range of 50 to 60 hectares (120 to 150 acres) optimal habitat. Hen territories are about 40 hectares (100 acres). The annual range can be several square kilometres (hundreds of hectares) when storms and heavy snowfall force the birds to winter at lower altitudes. Territories of cocks and hens may overlap.

Western capercaillie are diurnal game, i.e., their activity is limited to the daylight hours. They spend the night in old trees with horizontal branches. These sleeping trees are used for several nights; they can be mapped easily as the ground under them is covered by pellets.

The hens are ground breeders and spend the night on the nest. As long as the young chicks cannot fly the hen spends the night with them in dense cover on the ground. During winter the hens rarely go down to the ground and most tracks in the snow are from cocks.

Diet

The western capercaillie lives on a variety of food types, including buds, leaves, berries, insects, grasses and in the winter mostly conifer needles. One can see the food remains in their droppings, which are about 1 cm (1⁄2 in) in diameter and 5–6 cm (2–2 1⁄2 in) in length. Most of the year the droppings are of solid consistency but, with the ripening of blueberries, these dominate the diet and the faeces become formless and bluish black.

The western capercaillie is a highly specialized herbivore, which feeds almost exclusively on blueberry leaves and berries with some grass seeds and fresh shoots of sedges in summertime. The young chicks are dependent on protein-rich food in their first weeks and thus mainly prey on insects. Available insect supply is strongly influenced by weather—dry and warm conditions allow a fast growth of the chicks, cold and rainy weather leads to high mortality.

During winter, when a high snow cover prevents access to ground vegetation, the western capercaillie spends almost all day and night in trees, feeding on coniferous needles of spruce, pine and fir as well as on buds from beech and rowan.

To digest this coarse winter food, the birds need grit: small stones or gastroliths which they actively search for and devour. With their very muscular stomachs, gizzard stones function like a mill and break needles and buds into small particles. Additionally, western capercaillie have two appendixes which grow very long in winter. With the aid of symbiotic bacteria, the plant material is digested there. During the short winter days the western capercaillie feeds almost constantly and produces a pellet nearly every 10 minutes.

Courting and reproduction

.jpg)

The breeding season of the western capercaillie starts according to spring weather progress, vegetation development and altitude between March and April and lasts until May or June. Three-quarters of this long courting season is mere territorial competition between neighbouring cocks or cocks on the same courting ground.

At the very beginning of dawn, the tree courting begins on a thick branch of a lookout tree. The cock postures himself with raised and fanned tail feathers, erect neck, beak pointed skywards, wings held out and drooped and starts his typical aria to impress the females. The typical song in this display is a series of double-clicks like a dropping ping-pong ball, which gradually accelerate into a popping sound like a cork coming of a champagne bottle, which is followed by scraping sounds.

Towards the end of the courting season the hens arrive on the courting grounds, also called "leks", Swedish for "play". The cocks continue courting on the ground: This is the main courting season. The cock flies from his courting tree to an open space nearby and continues his display. The hens, ready to get mounted, crouch and utter a begging sound. If there is more than one cock on the lek, it is mainly the alpha-cock who engages in sexual intercourse with the hens. In this phase western capercaillies are most sensitive to disturbances. Even single human observers may cause the hens to fly off and prevent copulation in this very short time span where they are ready for conception.

In Nordic countries male western capercaillies are reputed for their combatative behavior during mating season, sometimes chasing off any people who enter their territory.[11][12][13] In a study it was found that the testosterone level in such "deviant" males was about five times higher than that of normal displaying males.[14]

There is a smaller courting peak in autumn, which serves to delineate the territories for the winter months and the next season.

Egg-laying

About three days after copulation the hen starts laying eggs. In 10 days the clutch is full. The average clutch size is eight eggs but may amount up to 12, rarely only four or five eggs. Brooding lasts about 26–28 days according to weather and altitude.

At the beginning of the brooding season, the hens are very sensitive to disturbances and leave the nest quickly. Towards the end they tolerate disturbances to a certain degree, crouching on their nest which is usually hidden under low branches of a young tree or a broken tree crown. As hatching nears, hens sit tighter on the nest and will only flush from the nest if disturbed in very close proximity. Nesting hens rarely spend more than an hour a day off of the nest feeding and as such become somewhat constipated. The presence of a nest nearby is often indicated by distinctively enlarged and malformed droppings known as "clocker droppings". All eggs hatch in close proximity after which the hen and clutch abandon the nest where they are at their most vulnerable. Abandoned nests often contain "caeacal" droppings; the discharge from the hens' appendixes built up over the incubation period.

Hatching and growth

After hatching the chicks are dependent on getting warmed by the hen. Like all precocial birds, the young are fully covered by down feathers at hatching but are not able to maintain their body temperature which is 41 °C (106 °F) in birds. In cold and rainy weather the chicks need to get warmed by the hen every few minutes and all night.

They seek food independently and prey mainly on insects, like butterfly caterpillars and pupae, ants, myriapodae, ground beetles.

They grow rapidly and most of the energy intake is transformed into the protein of the flight musculature (the white flesh around the breast in chickens). At an age of 3–4 weeks they are able to perform their first short flights. From this time on they start to sleep in trees on warm nights. At an age of about 6 weeks they are fully able to maintain their body temperature. The down feathers have been moulted into the immature plumage and at an age of 3 months another moult brings in their subadult plumage; now the two sexes can be easily distinguished.

From the beginning of September the families start to dissolve. First the young cocks disperse, then the young hens. Both sexes may form loose foraging groups over the winter.

Predation and hunting

Mammalian predators known to take capercaillie include Eurasian lynx (Lynx lynx) and gray wolf (Canis lupus), although they prefer slightly larger prey. Meanwhile, European pine martens (Martes martes), beech martens (Martes foina), brown bears (Ursus arctos), wild boars (Sus scrofa) and red foxes (Vulpes vulpes) take mostly eggs and chicks but can attack adults if they manage to ambush the often wary birds.[15][16][17][18][19] In Sweden, western capercaillies are the primary prey of the golden eagle (Aquila chrysaetos).[20] Large numbers are taken by northern goshawks (Accipiter gentilis), including adults but usually young ones, and Eurasian eagle-owls (Bubo bubo) will occasionally pick off a capercaillie of any age or size; they normally prefer mammalian foods.[21][22] White-tailed eagles (Haliaeetus albicilla) are more likely to take water birds than upland-type birds but have been recorded preying on capercaillie around the White Sea.[23]

A traditional gamebird, the capercaillie has been widely hunted with guns and dogs throughout its territory in central and northern Europe. This includes trophy hunting and hunting for food. Since hunting has been restricted in many countries, trophy-hunting has become a tourist resource, particularly in Central European countries. In some areas, declines are due to excessive hunting, though this has not generally been a global problem. The bird has not been hunted in Scotland or Germany for over 30 years.[24]

References

- BirdLife International (2016). "Tetrao urogallus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T22679487A85942729. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T22679487A85942729.en. Retrieved 14 March 2019.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- BirdLife International and NatureServe (2014) Bird Species Distribution Maps of the World. 2012. Tetrao urogallus. In: IUCN 2014. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2014.3. http://www.iucnredlist.org. Downloaded on 02 June 2015.

- Lockwood, W.B. (1993). The Oxford Dictionary of British Bird Names. OUP. ISBN 978-0198661962.

- Jobling, James A (2010). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London: Christopher Helm. pp. 383, 397. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4.

- Linnaeus, Carl (1758). Systema naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Tomus I. Editio decima, reformata (in Latin). Holmiae (Stockholm): Laurentii Salvii. p. 159.

F. cera pedibusque flavis, dorso fusco, nucha alba abdomine pallido maculis oblongis fuseis.

- https://www.hbw.com/species/western-capercaillie-tetrao-urogallus

- "Capercaillie (Tetrao urogallus)". ARKive. Archived from the original on 2012-08-23. Retrieved 2012-12-26.

- "Western capercaillie". World Association of Zoos and Aquariums (WAZA). Archived from the original on 2011-01-07. Retrieved 2012-06-21.

- Dunning, John B. Jr., ed. (1992). CRC Handbook of Avian Body Masses. CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-8493-4258-5.

- "Capercaillie". BBC Nature – Wildlife. Archived from the original on 2017-10-21. Retrieved 2012-06-21.

- "Sex-crazed grouse terrorizes Swedish family". The Local. 3 May 2015. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- Suter, Paul. "Capercaillie in Finland". Too Much To See. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- "Capercaillie". Harjureitti. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- MILONOFF, M (December 1992). "The abnormal conduct of capercaillies Tetrao urogallus". Hormones and Behavior. 26 (4): 556–567. doi:10.1016/0018-506X(92)90022-N.

- Odden, J.; Linnell, J.D.; Andersen, R. (2006). "Diet of Eurasian lynx, Lynx lynx, in the boreal forest of southeastern Norway: the relative importance of livestock and hares at low roe deer density". European Journal of Wildlife Research. 52 (4): 237–244. doi:10.1007/s10344-006-0052-4.

- Müller, S. (2006). Diet composition of wolves (Canis lupus) on the Scandinavian peninsula determined by scat analysis (PDF) (Thesis). School of Forest Science and Resource Management, Technical University of München, Germany. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2015-05-01.

- Saniga, M. (2002). "Nest loss and chick mortality in capercaillie (Tetrao urogallus) and hazel grouse (Bonasa bonasia) in West Carpathians". Folia Zoologica-Praha. 51 (3): 205–214.

- Wegge, P.; Kastdalen, L. (January 2007). "Pattern and causes of natural mortality of capercaille, Tetrao urogallus, chicks in a fragmented boreal forest" (PDF). Annales Zoologici Fennici: 141–151. ISSN 0003-455X.

- Smedshaug, C.A.; Selås, V.; Lund, S.E.; Sonerud, G.A. (1999). "The effect of a natural reduction of red fox Vulpes vulpes on small game hunting bags in Norway". Wildlife Biology. 5 (3): 157–166.

- Tjernberg, Martin (1981). "Diet of the Golden Eagle Aquila chrysaetos during the Breeding Season in Sweden". Holarctic Ecology. 4 (1): 12–19. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0587.1981.tb00975.x.

- Kenward, R. (2006). The Goshawk. London: Poyser Monographs, T. & A.D. Poyser / A. & C. Black. ISBN 978-0713665659.

- Voous, K.H. (1988). Owls of the Northern Hemisphere. MIT Press. ISBN 978-0262220354.

- Koryakin, A.S.; Boyko, N.S. (November 2005). The White tailed Sea Eagle Haliaeetus albicilla and the Common Eider Somate ria mollissima in the Gulf of Kandalaksha, White Sea. Proceedings of the Workshop, Kostomuksha. Status of Raptor Populations in Eastern Fennoskandia. Karelia, Russia. pp. 49–55.

- "Capercaillie Life Project". Retrieved 2015-12-25.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tetrao urogallus. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Tetrao urogallus |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Capercally. |

- Capercaillie mating game on the Internet Bird Collection

- Capercaillie at RSPB Birds by Name

- Aigas Field Centre Capercaillie Ecology and breeding programme pages

- Western Capercaillie—pictures in nature photographer Janne Heimonen's photo gallery

- BirdLife species factsheet for Tetrao urogallus

- "Tetrao urogallus". Avibase.

- "Western capercaillie media". Internet Bird Collection.

- Western capercaillie photo gallery at VIREO (Drexel University)

- Interactive range map of Tetrao urogallus at IUCN Red List maps

- Audio recordings of Western capercaillie on Xeno-canto.