Ring-tailed cat

The ringtail (Bassariscus astutus) is a mammal of the raccoon family native to arid regions of North America. It is widely distributed and well adapted to disturbed areas. It has been legally trapped for its fur. It is listed as Least Concern on the IUCN Red List.[1] It is also known as the ringtail cat, ring-tailed cat, miner's cat or bassarisk, and is sometimes called a cacomistle, though this term seems to be more often used to refer to Bassariscus sumichrasti.

| Ringtail | |

|---|---|

| |

| Ringtail in Phoenix, Arizona | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Family: | Procyonidae |

| Genus: | Bassariscus |

| Species: | B. astutus |

| Binomial name | |

| Bassariscus astutus (Lichtenstein, 1830) | |

| Subspecies | |

| |

| |

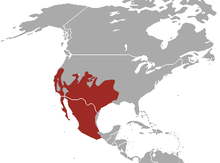

| Ring-tailed cat range | |

Description

The ringtail is buff to dark brown in color with pale underparts. Ringtails have a pointed muzzle with long whiskers resembles that of a fox (its Latin name means ‘clever little fox’) and its body resembles that of a cat. These animals are characterized by a long black and white "ringed" tail with 14–16 stripes,[2] which is the about the same length as its body. The claws are short, straight, and semi-retractable, well-suited for climbing.[3]

Smaller than a house cat, it is one of the smallest extant procyonids (only the smallest in the olingo species group average smaller). Its body alone measures 30–42 cm (12–17 in) and its tail averages 31–44 cm (12–17 in) from its base. It typically weighs around 0.7 to 1.5 kg (1.5 to 3.3 lb).[4] Its dental formula is 3.1.4.23.1.4.2 = 40.[5]

Ringtails are primarily nocturnal, with large eyes and upright ears that make it easier for them to navigate and forage in the dark. An adept climber, it uses its long tail for balance. The rings on its tail can also act as a distraction for predators. The white rings act as a target, so when the tail rather than the body is caught, the ringtail has a greater chance of escaping.[6]

Ringtails have occasionally been hunted for their pelts, but the fur is not especially valuable.

Ecology

In areas with a bountiful source of water, as many as 50 ringtails/sq. mile have been found. Ranging from 50 to 100 acres, the territories of male ringtails occasionally intersect with several females.[7] It has been suggested that ringtails use feces as a way to mark territory. In 2003, a study done in Mexico City found that ringtails tended to defecate in similar areas in a seemingly nonrandom pattern, mimicking that of other carnivores that utilized excretions to mark territories.[8]

Ringtails prefer a solitary existence but may share a den or be found mutually grooming one another. They exhibit limited interaction except during the breeding season, which occurs in the early spring. Ringtails can survive for long periods on water derived from food alone, and have urine which is more concentrated than any other mammal studied, an adaptation that allows for maximum water retention. [9]

Foxes, coyotes, raccoons, bobcats, hawks, and owls will opportunistically prey upon ringtails of all ages, though predominantly on younger, more vulnerable specimens.[4] Also occasional prey to coatis, lynxes, and mountain lions, the ringtail is rather adept at avoiding predators. The ringtail's success in deterring potential predators is largely attributed to its ability to excrete musk when startled or threatened. The main predators of the ringtail are the Great Horned Owl and the Red-tailed Hawk.[7]

Range and habitat

The ringtail is found in the southwestern United States in southern Oregon, California, eastern Kansas, Oklahoma, Arizona, New Mexico, Colorado, southern Nevada, Utah, and Texas. In Mexico it ranges from the northern desert state of Baja California to Oaxaca. Its distribution overlaps that of B. sumichrasti in the Mexican states of Guerrero, Oaxaca and Veracruz.[1] It has been reported to be living in western Louisiana, although no conclusive evidence has been found to support this. The ringtail is the state mammal of Arizona.[10]

It is commonly found in rocky desert habitats, where it nests in the hollows of trees or abandoned wooden structures. The ringtail has been found throughout the Great Basin Desert, which stretches over several states (Nevada, Utah, California, Idaho, and Oregon) as well as the Sonoran Desert in Arizona, and the Chihuahuan Desert in New Mexico, Texas, and northern Mexico. The ringtail also prefers rocky habitats associated with water, such as the riparian canyons, caves, or mine shafts.

The ankle joint is flexible and is able to rotate over 180 degrees, making it an agile climber. Their long tail provides balance for negotiating narrow ledges and limbs, even allowing them to reverse directions by performing a cartwheel. Ringtails also can ascend narrow passages by stemming (pressing all feet on one wall and their back against the other or pressing both right feet on one wall and both left feet on the other), and wider cracks or openings by ricocheting between the walls.[2]

Habits

Much like the common raccoon, the ringtail is nocturnal and solitary. It is also timid towards humans and seen much less frequently than raccoons. Despite its shy disposition and small body size, the ringtail is arguably the most actively carnivorous species of procyonid, as even the closely related cacomistle eats a larger portion of fruits, insects and refuse.

They produce a variety of sounds, including clicks and chatters reminiscent of raccoons. A typical call is a very loud, plaintive bark. As adults, these mammals lead solitary lives, generally coming together only to mate.

Ringtails have been reported to exhibit fecal marking behavior as a form of intraspecific communication to define territory boundaries or attract potential mates.[11]

Diet

Small vertebrates such as passerine birds, rats, mice, squirrels, rabbits, snakes, lizards, frogs, and toads are the most important foods during winters.[4] However, the ringtail is omnivorous, as are all procyonids. Berries and insects are important in the diet year-round, and become the primary part of the diet in spring and summer, along with other fruit.[12]

As an omnivore the ringtail enjoys a variety of foods in its diet, the majority of which is made up of animal matter. Insects and small mammals such as rabbits, mice, rats and ground squirrels are some examples of the ringtail's carnivorous tendencies. Occasionally the ringtail will also eat fish, lizards, birds, snakes and carrion. The ringtail also enjoys juniper, hack and black berries, persimmon, prickly pear, and fruit in general. They have even been observed partaking from hummingbird feeders, sweet nectar or sweetened water.[7] In one study the scat of ringtails located on the island of San Jose were analyzed. The results showed that the ringtail tended to prey on whatever was most abundant during each respective season. During the spring time the ringtail's diet consisted largely of insects, showing up in about 50% of the analyzed feces. Small rodents, snakes and some species of lizard were also present. Plant matter also presented in large amounts, around 59% of the collected feces contained some type of plant. The fruits Phaulothamnus, Lycium and Solanum were the most common. Characterized by their large amount of seeds, and ironwood leaves, these fleshy fruits were an obvious favorite of the ringtail.[13]

Reproduction

Ringtails mate in the spring. The gestation period is 45–50 days, during which the male will procure food for the female. There will be 2–4 cubs in a litter. The cubs open their eyes after a month, and will hunt for themselves after four months. They reach sexual maturity at ten months. The ringtail's lifespan in the wild is about seven years.

Domestication

The ringtail is said to be easily tamed, and can make an affectionate pet, and effective mouser. Miners and settlers once kept pet ringtails to keep their cabins free of vermin; hence, the common name of "miner's cat" (though in fact the ring-tail is no more a cat than it is civet).[14] The ringtails would move into the miners' and settlers' encampments and become accepted by humans in much the same way that some early domestic cats were theorized to have done. At least one biologist in Oregon has joked that the ringtail is one of two species – the domestic cat and the ringtail – that thus "domesticated humans" due to that pattern of behavior.

Often a hole was cut in a small box and placed near a heat source (perhaps a stove) as a dark, warm place for the animal to sleep during the day, coming out after dark to rid the cabin of mice.

References

- Reid, F.; Schipper, J. & Timm, R. (2016). "Bassariscus astutus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T41680A45215881.

- Lu, Julie. "The Biogeography of Ringtailed Cats". San Francisco University. Archived from the original on August 10, 2010. Retrieved December 25, 2010.

- Poglayen-Neuwall, Ivo; Toweill, Dale E. (1988). "Bassariscus astutus" (PDF). Mammalian Species (327): 1–8. doi:10.2307/3504321. JSTOR 3504321.

- Hunter, Luke (2011) Carnivores of the World, Princeton University Press, ISBN 9780691152288

- Stangl, Frederick B.; Henry- Langston, Sarah; Lamar, Nicholas; Kasper, Stephen (2014). "Sexual Dimorphism in the Ringtail (Bassariscus astutus) from Texas". Natural Science Research Laboratory. 328.

- Bibliography Gilbert, Bil. "Ringtails." Smithsonian 2000(5): 65-70. ProQuest. Web. 2 Apr. 2015 .

- Gilbert, Bil. "Ringtails." Smithsonian 08 2000: 65-70. ProQuest. Web. 2 Apr. 2015 .

- Barja I, List R. 2006. Faecal marking behaviour in ringtails (Bassariscus astutus) during the non-breeding period: Spatial characteristics of latrines and single faeces. Chemoecology. 16: 219–222.

- Schoenherr, Allen A. 1992. A Natural History of California. University of California Press. p. 386

- State mammal, Arizona State Library, Archives, & Public Records, retrieved May 24, 2019

- Barja, Isabel; List, Rurik (December 1, 2006). "Faecal marking behaviour in ringtails (Bassariscus astutus) during the non-breeding period: spatial characteristics of latrines and single faeces". Chemoecology. 16 (4): 219–222. doi:10.1007/s00049-006-0352-x. ISSN 0937-7409.

- Ringtail (Bassariscus astutus). Nsrl.ttu.edu. Retrieved on April 17, 2013.

- Rodríguez-Estrella, Ricardo, Angel Rodríguez Moreno, and Karina G. Tam. "Spring Diet of the Endemic Ring-tailed Cat (Bassariscus astutus insulicola) Population on an Island in the Gulf of California, Mexico." Journal of Arid Environments. 2nd ed. Vol. 44. N.p.: n.p., n.d. 241-46. Print.

- Ringtails in Redwood Park

Further reading

- Nowak, Ronald M. (2005). Walker's Carnivores of the World. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-8032-7

External links

| Wikispecies has information related to Bassariscus astutus |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bassariscus astutus. |

- Bassariscus astutus – Animal Diversity Web

- Smithsonian Institution – North American Mammals: Bassariscus astutus