Pskov

Pskov (Russian: Псков, IPA: [pskof] (![]()

Pskov Псков | |

|---|---|

City[1] | |

Aerial view of Pskov near the Kremlin | |

.svg.png) Flag  Coat of arms | |

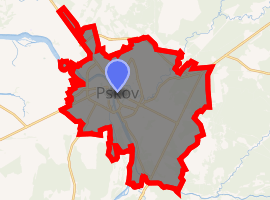

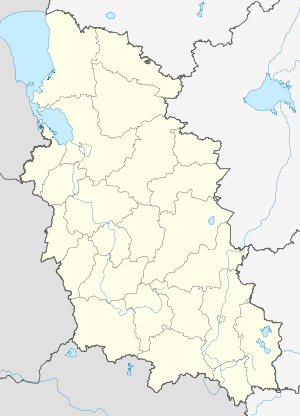

Location of Pskov

| |

Pskov Location of Pskov  Pskov Pskov (Pskov Oblast) | |

| Coordinates: 57°49′N 28°20′E | |

| Country | Russia |

| Federal subject | Pskov Oblast[1] |

| First mentioned | 903 |

| Government | |

| • Body | City Duma |

| • City Head | Ivan Tsetsersky |

| Elevation | 45 m (148 ft) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 203,279 |

| • Estimate (2018)[3] | 210,501 (+3.6%) |

| • Rank | 91st in 2010 |

| • Subordinated to | City of Pskov[1] |

| • Capital of | Pskov Oblast, Pskovsky District |

| • Urban okrug | Pskov Urban Okrug[4] |

| • Capital of | Pskov Urban Okrug[4], Pskovsky Municipal District[4] |

| Time zone | UTC+3 (MSK |

| Postal code(s)[6] | 180xxx |

| Dialing code(s) | +7 8112 |

| OKTMO ID | 58701000001 |

| City Day | July 23 |

| Website | www |

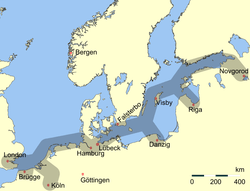

Pskov is one of the oldest cities in Russia. It served as the capital of the Pskov Republic and was a trading post of the Hanseatic League. Later it came under the control of the Grand Duchy of Moscow and the subsequent Russian Empire.

History

Early history

Pskov is one of the oldest cities in Russia. The name of the city, originally Pleskov (historic Russian spelling Плѣсковъ, Plěskov), may be loosely translated as "[the town] of purling waters". It was historically known in English as Plescow.[9] Its earliest mention comes in 903, which records that Igor of Kiev married a local lady, St. Olga. Pskovians sometimes take this year as the city's foundation date, and in 2003 a great jubilee took place to celebrate Pskov's 1,100th anniversary.

The first prince of Pskov was Vladimir the Great's youngest son Sudislav. Once imprisoned by his brother Yaroslav, he was not released until the latter's death several decades later. In the 12th and 13th centuries, the town adhered politically to the Novgorod Republic. In 1241, it was taken by the Teutonic Knights, but Alexander Nevsky recaptured it several months later during a legendary campaign dramatized in Sergei Eisenstein's 1938 movie Alexander Nevsky.

In order to secure their independence from the knights, the Pskovians elected a Lithuanian prince, named Daumantas, a Roman Catholic converted to Orthodox faith and known in Russia as Dovmont, as their military leader and prince in 1266. Having fortified the town, Daumantas routed the Teutonic Knights at Rakvere and overran much of Estonia. His remains and sword are preserved in the local kremlin, and the core of the citadel, erected by him, still bears the name of "Dovmont's town".

Pskov Republic

By the 14th century, the town functioned as the capital of a de facto sovereign republic. Its most powerful force was the merchants who brought the town into the Hanseatic League. Pskov's independence was formally recognized by Novgorod in 1348. Several years later, the veche promulgated a law code (called the Pskov Charter), which was one of the principal sources of the all-Russian law code issued in 1497.

For Russia, the Pskov Republic was a bridge towards Europe; for Europe, it was a western outpost of Russia. Already in the 13th century German merchants were present in Zapskovye area of Pskov and the Hanseatic League had a trading post in the same area in the first half of 16th century which moved to Zavelichye after a fire in 1562.[10][11] The wars with Livonian Order, Poland-Lithuania and Sweden interrupted the trade but it was maintained until the 17th century, with Swedish merchants gaining the upper hand eventually.[11]

The importance of the city made it the subject of numerous sieges throughout its history. The Pskov Krom (or Kremlin) withstood twenty-six sieges in the 15th century alone. At one point, five stone walls ringed it, making the city practically impregnable. A local school of icon-painting flourished, and the local masons were considered the best in Russia. Many peculiar features of Russian architecture were first introduced in Pskov.

Finally, in 1510, the city fell to Muscovite forces.[12] The deportation of noble families to Moscow under Ivan IV in 1570 is a subject of Rimsky-Korsakov's opera Pskovityanka (1872). As the second largest city of the Grand Duchy of Moscow, Pskov still attracted enemy armies. Most famously, it withstood a prolonged siege by a 50,000-strong Polish army during the final stage of the Livonian War (1581–1582). The king of Poland Stephen Báthory undertook some thirty-one attacks to storm the city, which was defended mainly by civilians. Even after one of the city walls was broken, the Pskovians managed to fill the gap and repel the attack. "It's amazing how the city reminds me of Paris", wrote one of the Frenchmen present at Báthory's siege.

Modern history

Peter the Great's conquest of Estonia and Livonia during the Great Northern War in the early 18th century spelled the end of Pskov's traditional role as a vital border fortress and a key to Russia's interior. As a consequence, the city's importance and well-being declined dramatically, although it served as a seat of separate Pskov Governorate since 1777.

During World War I, Pskov became the center of much activity behind the lines. It was at a railroad siding in Pskov, aboard the imperial train, that Tsar Nicholas II signed the manifesto announcing his abdication in March 1917, and after the Russo-German Brest-Litovsk Peace Conference (December 22, 1917 – March 3, 1918), the Imperial German Army invaded the area. Pskov was also occupied by the Estonian army between 25 May 1919 and 28 August 1919 during the Estonian War of Independence when the White Russian commander Stanisław Bułak-Bałachowicz became the military administrator of Pskov. He personally ceded most of his responsibilities to a democratically elected municipal duma and focused on both cultural and economical recovery of the war-impoverished city. He also put an end to censorship of press and allowed for creation of several socialist associations and newspapers.

Under the Soviet government, large parts of the city were rebuilt, many ancient buildings, particularly churches, were demolished to give space for new constructions. During World War II, the medieval citadel provided little protection against modern artillery of Wehrmacht, and Pskov suffered substantial damage during the German occupation from July 9, 1941 until July 23, 1944. A huge portion of the population died during the war, and Pskov has since struggled to regain its traditional position as a major industrial and cultural center of Western Russia.

Administrative and municipal status

Pskov is the administrative center of the oblast and, within the framework of administrative divisions, it also serves as the administrative center of Pskovsky District, even though it is not a part of it.[1] As an administrative division, it is incorporated separately as the City of Pskov—an administrative unit with the status equal to that of the districts.[1] As a municipal division, the City of Pskov is incorporated as Pskov Urban Okrug.[4]

Landmarks and sights

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|---|---|

The mid-12th-century cathedral of St. John. Dozens of similar quaint little churches are scattered throughout Pskov. | |

| Criteria | Cultural: (ii) |

| Reference | 1523 |

| Inscription | 2019 (43rd session) |

| Area | 29.32 ha (72.5 acres) |

| Buffer zone | 625.6 ha (1,546 acres) |

Pskov still preserves much of its medieval walls, built from the 13th century on. Its medieval citadel is called either the Krom or the Kremlin. Within its walls rises the 256-foot-tall (78 m) Trinity Cathedral, founded in 1138 and rebuilt in the 1690s. The cathedral contains the tombs of saint princes Vsevolod (died in 1138) and Dovmont (died in 1299). Other ancient cathedrals adorn the Mirozhsky Monastery (completed by 1152), famous for its 12th-century frescoes, St. John's (completed by 1243), and the Snetogorsky monastery (built in 1310 and stucco-painted in 1313).

Pskov is exceedingly rich in tiny, squat, picturesque churches, dating mainly from the 15th and the 16th centuries. There are many dozens of them, the most notable being St. Basil's on the Hill (1413), St. Kozma and Demian's near the Bridge (1463), St. George's from the Downhill (1494), Assumption from the Ferryside (1444, 1521), and St. Nicholas' from Usokha (1536). The 17th-century residential architecture is represented by merchant mansions, such as the Salt House, the Pogankin Palace, and the Trubinsky mansion.

Among the sights in the vicinity of Pskov are Izborsk, a seat of Rurik's brother in the 9th century and one of the most formidable fortresses of medieval Russia; the Pskov Monastery of the Caves, the oldest continually functioning monastery in Russia (founded in the mid-15th century) and a magnet for pilgrims from all over the country; the 16th-century Krypetsky Monastery; Yelizarov Convent, which used to be a great cultural and literary center of medieval Russia; and Mikhaylovskoye, a family home of Alexander Pushkin where he wrote some of the best known lines in the Russian language. The national poet of Russia is buried in the ancient cloister at the Holy Mountains nearby. Unfortunately, the area presently has only a minimal tourist infrastructure, and the historic core of Pskov requires serious investments to realize its great tourist potential.

On 7 July 2019, the Churches of the Pskov School of Architecture was inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.[13]

Geography

Climate

The climate of Pskov is humid continental (Köppen climate classification Dfb) with maritime influences due to the city's relative proximity to the Baltic Sea and Gulf of Finland; with relative soft (for Russia) but long winter (usually five months per year) and warm summer. Summer and fall have more precipitation than winter and spring.

| Climate data for Pskov | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 9.8 (49.6) |

11.3 (52.3) |

18.5 (65.3) |

27.6 (81.7) |

32.0 (89.6) |

33.6 (92.5) |

35.0 (95.0) |

35.6 (96.1) |

30.3 (86.5) |

22.6 (72.7) |

14.1 (57.4) |

12.4 (54.3) |

35.6 (96.1) |

| Average high °C (°F) | −2.7 (27.1) |

−2.4 (27.7) |

2.8 (37.0) |

11.3 (52.3) |

17.9 (64.2) |

21.1 (70.0) |

23.6 (74.5) |

21.8 (71.2) |

15.7 (60.3) |

9.2 (48.6) |

2.2 (36.0) |

−1.6 (29.1) |

9.9 (49.8) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −5.1 (22.8) |

−5.7 (21.7) |

−1.1 (30.0) |

6.1 (43.0) |

12.2 (54.0) |

15.8 (60.4) |

18.3 (64.9) |

16.5 (61.7) |

11.1 (52.0) |

5.8 (42.4) |

0.0 (32.0) |

−3.8 (25.2) |

5.8 (42.4) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −7.9 (17.8) |

−9.1 (15.6) |

−4.7 (23.5) |

1.4 (34.5) |

6.6 (43.9) |

10.7 (51.3) |

13.0 (55.4) |

11.5 (52.7) |

7.0 (44.6) |

2.8 (37.0) |

−2.3 (27.9) |

−6.3 (20.7) |

1.9 (35.4) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −40.6 (−41.1) |

−37.6 (−35.7) |

−29.7 (−21.5) |

−20.9 (−5.6) |

−5.1 (22.8) |

−0.1 (31.8) |

2.7 (36.9) |

1.3 (34.3) |

−4.6 (23.7) |

−12.5 (9.5) |

−23.8 (−10.8) |

−40.3 (−40.5) |

−40.6 (−41.1) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 47 (1.9) |

36 (1.4) |

37 (1.5) |

33 (1.3) |

55 (2.2) |

92 (3.6) |

76 (3.0) |

94 (3.7) |

68 (2.7) |

63 (2.5) |

54 (2.1) |

48 (1.9) |

702 (27.6) |

| Average rainy days | 9 | 7 | 9 | 12 | 15 | 18 | 16 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 14 | 10 | 161 |

| Average snowy days | 22 | 20 | 14 | 5 | 1 | 0.03 | 0 | 0 | 0.03 | 3 | 13 | 20 | 98 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 87 | 84 | 80 | 70 | 67 | 72 | 74 | 78 | 83 | 86 | 88 | 89 | 80 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 41 | 71 | 136 | 189 | 279 | 300 | 285 | 233 | 152 | 90 | 34 | 25 | 1,835 |

| Source 1: Pogoda.ru.net[14] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: NOAA (sun 1961–1990)[15] | |||||||||||||

Gallery

A Russian coin commemorating Pskov's 1,100th anniversary

A Russian coin commemorating Pskov's 1,100th anniversary

Economy

- JSC "AVAR" (AvtoElectroArmatura). Electric equipment production for cars, lorries buses and tractors (relays, switches, fuses, electronic articles)

- Pskov is served by Pskov Airport which was also used for military aviation.

Notable people

- Valery Alekseyev (born 1979), professional association football player

- Alexander Bastrykin (born 1953), Head of The Investigative Committee of Russia

- Nina Cheremisina (born 1946), former rower

- Valentin Chernykh (1935–2012), screenwriter

- Semyon Dimanstein 1886-1938, Soviet state activist, killed in Stalin's purges, a representative of the Soviet Jews

- Mariya Fadeyeva (born 1958), former rower

- Sergei Fedorov (born 1969), hockey player

- Oxana Fedorova (born 1977), Miss Russia 2001, Miss Universe 2002

- Mikhail Golitsyn (1639–1687), statesman, governor of Pskov

- Veniamin Kaverin (1902–1989), writer

- Yakov Knyazhnin (1740–1791), foremost tragic author

- Vasily Kuptsov (1899–1935), painter

- Oleg Lavrentiev (1926–2011), Soviet, Russian and Ukrainian physicist

- Kronid Lyubarsky (1934–1996), journalist, dissident, human rights activist

- Sergey Matveyev (born 1972), former Olympic rower

- Boris Meissner (1915–2003), German lawyer and social scientist

- Mikhail Minin (1922–2008), First soldier to hoist the Soviet flag atop the Reichstag building during the Battle of Berlin

- Igor Nedorezov (born 1981), professional footballer

- Elena Neklyudova (born 1973), singer-songwriter

- Alexander Nikolaev (born 1990), sprint canoer

- Afanasy Ordin-Nashchokin (1605–1680), one of the most important Russian statesmen of the 17th century

- Yulia Peresild (born 1984), stage and film actress

- Valery Prokopenko (1941–2010), honored citizen of the city, honored rowing coach of the USSR and Russian Federation

- Georg von Rauch (1904–1991) historian specializing in Russia and the Baltic states

- Svetlana Semyonova (born 1958), former rower

- Konstantin Shabanov (born 1989), track and field athlete

- Nikolai Skrydlov (1844–1918), admiral in the Imperial Russian Navy

- Vladimir Smirnov (born 1957), prominent Russian businessman

- Aleksei Snigiryov (born 1968), professional footballer

- Galina Sovetnikova (born 1955), former rower

- Marina Studneva (born 1959), former rower

- Ruslan Surodin (born 1982), professional footballer

- Grigory Teplov (1717–1779), academic administrator

- Valeri Tsvetkov (born 1977), professional footballer

- Nikita Vasilyev (born 1992), professional football player

- Sergei Vinogradov (born 1981), professional football player

- Aleksander von der Bellen (1859-1924), politician, provincial commissar of Pskov

- Maxim Vorobiev (1787–1855), landscape painter

- Ferdinand von Wrangel (1797–1870), explorer and seaman

- Vsevolod of Pskov, Novgorodian prince, canonized by the Russian Orthodox Church as Vsevolod-Gavriil

Twin towns – sister cities

References

Notes

- Law #833-oz

- Russian Federal State Statistics Service (2011). "Всероссийская перепись населения 2010 года. Том 1" [2010 All-Russian Population Census, vol. 1]. Всероссийская перепись населения 2010 года [2010 All-Russia Population Census] (in Russian). Federal State Statistics Service.

- "26. Численность постоянного населения Российской Федерации по муниципальным образованиям на 1 января 2018 года". Federal State Statistics Service. Retrieved January 23, 2019.

- Law #419-oz.

- "Об исчислении времени". Официальный интернет-портал правовой информации (in Russian). June 3, 2011. Retrieved January 19, 2019.

- Почта России. Информационно-вычислительный центр ОАСУ РПО. (Russian Post). Поиск объектов почтовой связи (Postal Objects Search) (in Russian)

- Russian Federal State Statistics Service (May 21, 2004). "Численность населения России, субъектов Российской Федерации в составе федеральных округов, районов, городских поселений, сельских населённых пунктов – районных центров и сельских населённых пунктов с населением 3 тысячи и более человек" [Population of Russia, Its Federal Districts, Federal Subjects, Districts, Urban Localities, Rural Localities—Administrative Centers, and Rural Localities with Population of Over 3,000] (XLS). Всероссийская перепись населения 2002 года [All-Russia Population Census of 2002] (in Russian).

- "Всесоюзная перепись населения 1989 г. Численность наличного населения союзных и автономных республик, автономных областей и округов, краёв, областей, районов, городских поселений и сёл-райцентров" [All Union Population Census of 1989: Present Population of Union and Autonomous Republics, Autonomous Oblasts and Okrugs, Krais, Oblasts, Districts, Urban Settlements, and Villages Serving as District Administrative Centers]. Всесоюзная перепись населения 1989 года [All-Union Population Census of 1989] (in Russian). Институт демографии Национального исследовательского университета: Высшая школа экономики [Institute of Demography at the National Research University: Higher School of Economics]. 1989 – via Demoscope Weekly.

- Bacon, George A (1889). The Academy: A Journal of Secondary Education, Volume 4. p. 403.

- Dollinger, Philippe (1999). The German Hansa. Psychology Press. p. 105. ISBN 9780415190732.

- Аракчеев владимир Анатольевич, Псков и Ганза в эпоху средневековья, ООО «Дизайн экспресс», 2012 (in Russian)

- Maclean, Fitzroy (March 18, 1979). Pskov: A Journey Into Russia's Past, The New York Times

- "Six cultural sites added to UNESCO's World Heritage List". UNESCO. July 7, 2019.

- "Pogoda.ru.net" (in Russian). Retrieved December 5, 2019.

- "Pskov Climate Normals 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved December 5, 2019.

- "Общая информация". pskovgorod.ru (in Russian). Pskov. Retrieved February 1, 2020.

Sources

- Псковское областное Собрание депутатов. Закон №833-оз от 5 февраля 2009 г. «Об административно-территориальном устройстве Псковской области». Вступил в силу со дня официального опубликования. Опубликован: "Псковская правда", №20, 10 февраля 2009 г. (Pskov Oblast Council of Deputies. Law #833-oz of February 5, 2009 On the Administrative-Territorial Structure of Pskov Oblast. Effective as of the official publication date.).

- Псковское областное Собрание депутатов. Закон №419-оз от 28 февраля 2005 г. «О границах и статусе действующих на территории области муниципальных образований». Вступил в силу со дня официального опубликования. Опубликован: "Псковская правда", №41–43, 4 марта 2005 г. (Pskov Oblast Council of Deputies. Law #419-ы. of February 28, 2005 On the Borders and Status of the Municipal Formations Existing on the Oblast Territory. Effective as of the official publication date.).

Bibliography

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Pskov. |

- Official website (in Russian)

- Nortfort.ru. Pskov fortress

- The Pskov Power. Archive of the Pskov area of regional studies

- Annette M. B. Meakin (1906). "Pskoff". Russia, Travels and Studies. London: Hurst and Blackett. OCLC 3664651. OL 24181315M.

- "Pskov". The Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). New York: Encyclopædia Britannica. 1910. OCLC 14782424.

- The murder of the Jews of Pskov during World War II, at Yad Vashem website

- Savignac, David (trans). The Pskov 3rd Chronicle.

- Pskov, Russia at JewishGen