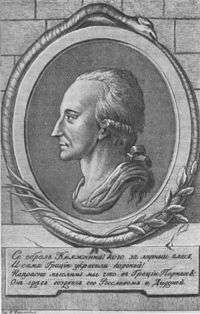

Yakov Knyazhnin

Yakov Borisovich Knyazhnin (Russian: Я́ков Бори́сович Княжни́н, November 3, 1742 or 1740, Pskov – January 1, 1791, St Petersburg) was Russia's foremost tragic author during the reign of Catherine the Great. Knyazhnin's contemporaries hailed him as the true successor to his father-in-law Alexander Sumarokov, but posterity, in the words of Vladimir Nabokov, tended to view his tragedies and comedies as "awkwardly imitated from more or less worthless French models".[1]

Biography

Knyazhnin was born into the family of the vice-governor of Pskov. From 1750 he studied in the gymnasium at the Academy in St Petersburg. In 1755 he was a cadet of the Justice Board; and in 1757 translator at the Construction Office. In 1762 he was in military service as a secretary of Kirill Razumovsky.

In 1770, he married Ekaterina Aleksandrovna Sumarokov. The couple had one of the most important literary salons in Russia.[2]

In 1773 he was sentenced to death for spending 6,000 roubles of fiscal money, however the sentence was reduced: he was deprived of the rank of officer and his nobility. In 1777 he obtained the forgiveness of the Empress Catherine II, and received back his nobility and officer rank. He was employed by Ivan Betskoy as his secretary. Soon he left into the resignation. He taught Russian Literature at the Military School. He was a member of Russian Academy from 1783.

The son of Knyazhnin in a biographic essay about this father wrote that he died of "catarrhal fever". This seems to be more accurate than another version, propagated by Pushkin, which claims that Knyazhnin died from torture at the hands of the secret police.

Legacy

Knyazhnin's contemporary success rested largely on his witty comedies The Braggart (1786) and The Cranks (1790). The latter revolves around the theme of favouritism, of the unexpectedly quick rise in rank, which was topical in Catherine's reign, and considered risqué.[3]

He also wrote six comic operas operas and eight tragedies, which, as D.S. Mirsky put it, "breathe an almost revolutionary spirit of political freethinking".[4] Almost everything he wrote was immediately published by the decree of Catherine the Great. Most of his plays and operas were staged at the Hermitage Theatre in St Petersburg.

Among his other works are poems and translations including works by Voltaire and Corneille. Writing his plays and opera librettos, Knyaznin often borrowed some ideas from Voltaire, Metastasio, Molière and Carlo Goldoni developing them and putting in different context. He imitated these models so extensively that Alexander Pushkin later referred to him as "Knyazhnin the Borrower" (or "derivative Knyazhnin" — «переимчивый Княжнин», see details).

Knyazhnin's last tragedy, Vadim of Novgorod (1789), was inspired by Catherine II's treatment of Vadim's revolt against Rurik in her own play From Ryurik's Life. Disputing with her, Knyazhnin depicted Vadim as a champion of Novgorod's ancient liberties who has to stab himself in the face of triumphant authoritorianism. When the play was posthumously published in 1793, the Empress had it banned as a "literary revolt". Against the background of the French Revolution, it was decided wise to burn all the copies. Vadim of Novgorod was never staged and was not reprinted in Russia until 1914.

Dramatic works

- Dido (Дидона – Didona), a tragedy 1769. Text. Comments.

- Olga (Ольга), a tragedy 1776–1778. Text. Comments.

- Rosslav (Росслав), a tragedy in 5 acts, publ. 1784 St Petersburg Text. Comments.

- Vadim the Bold or Vadim of Novgorod (Вадим Новгородский – Vadim Novgorogsky), a tragedy 1788 or 1789, publ. 1793. Text. Comments.

- The Braggart (Хвастун – Khvastun), a comedy 1784–1785 publ. 1786. Text. Comments.

- The Cranks (Чудаки – Chudaki), a comedy c1790, publ. 1793. Text. Comments.

- Misfortune from a Carriage (Несчастие от кареты – Neschactye ot karety) opera with music by Vasily Pashkevich, premiere: November 7, 1779, Hermitage Theatre. St Petersburg Text. Comments.

- The Miser (Скупой – Skupoy) opera with music by Vasily Pashkevich, c 1782. Fragments Comments.

- The Sbiten Vendor (Сбитенщик – Sbitenshchik) opera with music by Antoine Bullant also known as Anton Bullandt or Jean Bullant 1783. Fragments Comments.

- Orpheus (Орфей – Orfey) opera-melodrama with music by Giuseppe Torelli, premiere April 30, 1763, later with music by Yevstigney Fomin, premiere: February 5, 1795. Text. Comments.

Quotations

Волшебный край! там в стары годы, |

Enchanted land! There like a lampion |

| —Alexander Pushkin, Eugene Onegin, (Chapter I, XVIII) |

—Translated by Charles H. Johnston |

Bibliography

- Knyazhnin, Y. Sbitenscik. Il venditore di sbiten. Testo originale russo a fronte, a c. di Nicoletta Cabassi e Kumusch Imanalieva. Mantova: Universitas Studiorum, 2013, ISBN 978-88-97683-21-6

- Fomin, Yevstigney Ipat'yevich by Richard Taruskin, in 'The New Grove Dictionary of Opera', ed. Stanley Sadie (London, 1992) ISBN 0-333-73432-7

References

- Eugene Onegin: A Novel in Verse: Commentary. Princeton University Press, 1991. ISBN 0-691-01904-5. Page 82.

- Ledkovskai︠a︡-Astman, Marina; Rosenthal, Charlotte; Zirin, Mary Fleming (1994). Dictionary of Russian Women Writers. pp. 298–99. ISBN 0313262659.

- Robert Leach, Victor Borovsky. A History of Russian Theatre. Cambridge University Press, 1999. ISBN 0-521-43220-0. Page 70.

- D.S. Mirsky. A History of Russian Literature. Northwestern University Press, 1999. ISBN 0-8101-1679-0. Page 54.

External links

| Wikisource has the text of a 1920 Encyclopedia Americana article about Yakov Knyazhnin. |

- (in Russian) Biography

- (in Russian) Political prisoners

- (in Russian) Russian library online

- (in Russian) Selected works

- (in Russian) Life and work