Fort Pickens

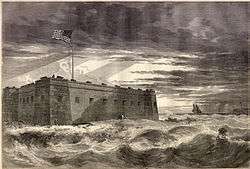

Fort Pickens is a pentagonal historic United States military fort on Santa Rosa Island in the Pensacola, Florida, area. It is named after American Revolutionary War hero Andrew Pickens. The fort was completed in 1834 and was one of the few forts in the South that remained in Union hands throughout the American Civil War. It remained in use until 1947. Fort Pickens is included within the Gulf Islands National Seashore, and as such, is administered by the National Park Service.

Fort Pickens | |

Panorama of Fort Pickens | |

| |

| Nearest city | Pensacola Beach, Florida |

|---|---|

| Area | 850 acres (340 ha) |

| Built | 1834 |

| NRHP reference No. | 72000096[1] |

| Added to NRHP | May 31, 1972 |

Design

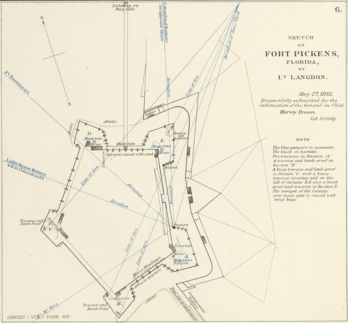

Fort Pickens was part of the Third System of Fortifications, meant to enhance the old earthworks and simple, obsolete designs of the First and Second System of Fortifications. Fort Pickens was of a Pentagonal design, with broader western walls to provide a wide range of fire over the bay.

The fort had a counterscarp to the east side exclusively, to create a defensive moat in the event that a land invasion came from the west. The westernmost Bastions were also equipped with mine chambers, to be detonated in a last-ditch-effort to save the fort from invaders.

History

After the War of 1812, the United States decided to fortify all of its major ports. French engineer Simon Bernard was appointed to design Fort Pickens. Construction lasted from 1829 to 1834, with 21.5 million bricks being used to build it. Much of the construction was done by slaves. Its construction was supervised by Colonel William H. Chase of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. During the American Civil War, he sided with the Confederacy and was appointed to command Florida's troops.

Fort Pickens was the largest of a group of fortifications designed to defend Pensacola Harbor. It supplemented Fort Barrancas, Fort McRee, and the Navy Yard. Located at the western tip of Santa Rosa Island, just offshore from the mainland, Fort Pickens guarded the island and the entrance to the harbor.

1858 fire

On the night of 20 January 1858, the USCS Robert J. Walker was at Pensacola when a major fire broke out at Fort Pickens. The cutter's men and boats, joined by the hydrographic party of the U.S. Coast Survey steamboat USCS Varina, rallied to fight the fire. The next day, the captain of the Robert J. Walker received a communication from Captain John Newton of the Army Corps of Engineers, who commanded the harbor of Pensacola, acknowledging the important service rendered by the Robert J. Walker.

Civil War

By the time of the American Civil War, Fort Pickens had not been occupied since shortly after the Mexican–American War. Despite its dilapidated condition, Lieutenant Adam J. Slemmer, in charge of United States forces at Fort Barrancas, decided Fort Pickens was the most defensible post in the area. He decided to abandon Fort Barrancas when, around midnight of January 8, 1861, his guards repelled a group of local civilians who intended to occupy the fort. Some historians claim that these were the first shots fired in the Civil War.

On January 10, 1861, the day Florida declared its secession from the Union, Slemmer destroyed over 20,000 pounds of gunpowder at Fort McRee. He then spiked the guns at Fort Barrancas, and moved his small force of 51 soldiers and 30 sailors to Fort Pickens. On January 15, 1861 and January 18, 1861, Slemmer refused surrender demands from Colonel William Henry Chase of the Florida militia. Chase had designed and constructed the fort as a captain in the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Slemmer defended the fort against threat of attack until he was reinforced and relieved on April 11, 1861 by Colonel Harvey Brown and the USS Brooklyn.

The Confederates attacked the Fort on October 9, 1861 in the Battle of Santa Rosa Island, with a force of a thousand men. The attack came from the east, after forces landed four miles away. The attack was repelled by artillery and gunfire, and the Confederates retreated with 90 casualties.

Bombardments

After tensions in Pensacola grew, and the Confederates secured posts at Fort McRee and Fort Barrancas, the Federal forces decided to shell the confederate forts. On November 22, two Union warships, the Niagara and the Richmond, sailed into the bay, and the bombardment began. The attack lasted two days, and the results were in the Union's favor. Fort McRee was nearly destroyed, and the town of Warrington and the Navy Yard were destroyed.

A second bombardment, meant to finish off the Confederates, was initiated on New Year's Day 1862. Fort McRee was almost destroyed, and any buildings near Fort Barrancas were burned.

Confederate Battery at Warrington opposite Fort Pickens

Confederate Battery at Warrington opposite Fort Pickens_(14760322774).jpg) J.D. Edwards photograph of Confederates occupying batteries outside Fort Pickens

J.D. Edwards photograph of Confederates occupying batteries outside Fort Pickens_(14759494611).jpg) J.D. Edwards photograph of Confederates occupying batteries outside Fort Pickens

J.D. Edwards photograph of Confederates occupying batteries outside Fort Pickens_(14782666493).jpg) J.D. Edwards photograph of Confederates occupying batteries outside Fort Pickens

J.D. Edwards photograph of Confederates occupying batteries outside Fort Pickens_(14762809165).jpg) J.D. Edwards photograph of rebels near lighthouse at Pensacola

J.D. Edwards photograph of rebels near lighthouse at Pensacola Confederate camp, Warrington Navy Yard, Pensacola, Florida, 1861 Company B of the 9th Mississippi Infantry Regiment

Confederate camp, Warrington Navy Yard, Pensacola, Florida, 1861 Company B of the 9th Mississippi Infantry Regiment

Confederate Surrender

Running low on supplies, and with dwindling morale, the Confederates began to doubt their chances of success in the Battle of Pensacola. Eventually, the Battle of Mobile Bay drew the last of the southern forces westward to Alabama to defend against Admiral Farragut's invasion forces. On May 10, 1862, the last Confederates at Pensacola surrendered to Fort Pickens.

Despite repeated Confederate threats, Fort Pickens was one of only four Southern forts to remain in Union hands throughout the war, the others being Fort Taylor at Key West, Florida, Fort Jefferson at Garden Key, Florida in the Dry Tortugas, and Fort Monroe in Virginia.

Indian wars

Captives from Indian Wars in the West were transported to the East Coast to be held as prisoners. From October 1886 to May 1887, Geronimo, a noted Apache war chief, was imprisoned in Fort Pickens, along with several of his warriors. Their families were held at Fort Marion in St. Augustine.[2]

Endicott era

During the late 1890s and early 20th century, the Army had new gun batteries constructed at Fort Pickens. These batteries were part of a program initiated by the Endicott Board, a group headed by a mid-1880s Secretary of War, William C. Endicott. Instead of many guns concentrated in a traditional thick-walled masonry structure, the Endicott batteries are spread out over a wide area, concealed behind concrete parapets flush with the surrounding terrain. The use of the accurate, long-range weapons eliminated the need for the concentration of guns that was common in the Third System fortifications. Battery Pensacola was constructed within the walls of Fort Pickens, while other similar concrete batteries were constructed to the east and west as separate facilities. The ruins of these later facilities are also included in the Gulf Islands National Seashore complex. As at many posts, obsolete weapons were repurposed during World War I; Battery Cooper's 6-inch M1905 guns on disappearing carriages were removed in 1917, but a piece located at West Point was moved to Battery Cooper in 1976.

Little consideration was given to the preservation of the old fort during the construction of Endicott Batteries. The parapet on The south wall of the fort was demolished, along with the officers' quarters beneath. The barbette on the southeast wall was also removed, along with the casemate arches of the southernmost bastion. These changes were made to allow the firing arc of Battery Pensacola's 12-inch Guns to clear with having to raise the battery.

| Battery Name | Constructed | Armament | Carriage Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| Battery Pensacola | 1899 | x2 12" | Disappearing |

| Battery Trueman | 1905 | x2 3" | Barbette |

| Battery Payne | 1904 | x2 3" | Barbette |

| Battery Cullum | 1898 | x2 10" | Disappearing |

| Battery Sevier | 1898 | x2 10" | Disappearing |

| Battery Cooper | 1904 | x2 6" | Disappearing |

| Battery Van Swearingen | 1898 | x2 4.7" | Barbette |

On June 20, 1899, a fire in Fort Pickens' Bastion D reached the bastion's magazine, which contained 8,000 pounds (3,600 kg) of powder. The resulting explosion killed one soldier and obliterated Bastion D. The force of the explosion was so great that bricks from Bastion D's walls landed across the bay at Fort Barrancas, more than 1.5 miles (2.4 km) away.[3] The damage was relatively confined to Bastion D, but the foundation were torn away along with sections of the walls to allow for easier access to the batteries. This proved easier than trying to fit the any mechanical equipment for Battery Pensacola through the Sally Port.

Post WW I

GPF Battery

As with many other forts, Panama mounts were planned for in the interwar era, beginning in 1937. Four 155mm GPF guns were placed around Battery Cooper, two forward, and one to each side, in 1942. The guns used a concrete ring for positioning and aiming, which still remain today. The guns, however, have been long since removed. The 155 battery used Cooper's magazines, communications, and other support facilities.

Battery Langdon

Battery Langdon was constructed in 1923, with 12-inch guns meant to complement those already in place at Battery Pensacola. The guns were originally exposed to fire, but the ammunition and command center was stored inside of a reinforced embankment between the guns. The guns were later casemated in 1943.

World War II

Fort Pickens was of interest in World War II to the U.S. Navy, and it was decided that the defenses of the fort needed to be strengthened. A specific threat was German U-Boats, which were already operating in the Gulf of Mexico.

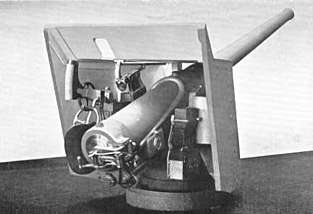

Battery 234

One addition to Fort Pickens's defense was Battery 234, which was meant to function alongside Battery 233 across the bay on Perdido Key. Many of these batteries were built across the nation, all with the same design, to replace the role of light artillery formerly held by the 3-Inch M1903 guns. Both batteries were designed to equip 6-Inch M1905 Guns in Cast-Steel casemates. The command center is buried underneath an artificial hill to protect from air attacks. The guns were never fitted, but were donated in 1976 by the Smithsonian.

Battery Langdon (1943)

To protect from the threat of German dive bombers, Battery Langdon was casemated in 1943. The 12-inch barbette guns that were in place were kept, but 17 feet of concrete was added to create a bomb proof bunker. The bunker was then covered in sand and dirt to create an artificial hill around the battery, for additional protection.

Nearby fortifications

Fort McRee was built on Perdido Key across Pensacola Pass from Fort Pickens. Abandoned by Union forces and taken over by Florida and Alabama militia in January 1861, it was badly damaged by Union bombardment during the American Civil War later that year. Abandoned by Confederate forces, Fort McRee remained in ruins for the next three decades. Although improved in the late 19th century during the run-up to the Spanish–American War, the fort was struck by a hurricane on September 26–27, 1906 that destroyed most of the newer structures erected since 1898. After the hurricane, only a minimal caretaker staff was based there to ensure security of the site. Due to its site being accessible only by foot or boat, Fort McRee was left to the elements. Storms and erosion have battered the site; today, nothing more than a few scattered foundations remain.

Fort Barrancas, which was built around previously constructed 17th- and 18th-century Spanish forts, as well as Fort Barrancas' associated Advanced Redoubt approximately a mile (1.6 km) to the northwest of Fort Barrancas, are located across Pensacola Bay on the grounds of what is now Naval Air Station Pensacola. When Union forces abandoned Fort McRee in 1861, they also abandoned Fort Barrancas, pulling back to Fort Pickens. This fort was also occupied by Florida and Alabama militia forces, who were subsequently integrated into the Confederate forces. In May 1862, after hearing that the Union Army had taken New Orleans, Confederate troops abandoned Pensacola and Fort Barrancas. The fort reverted to Union control.

References

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- "Gulf Islands National Seashore - The Apache (U.S. National Park Service)", nps.gov, retrieved 2009-05-24

- "Fort Pickens photos", University of South Florida

Bradford, introduction by James C. (2010). The big book of Civil War sites : from Fort Sumter to Appomattox, a visitor's guide to the history, personalities, and places of America's battlefields. Guilford, Conn.: Globe Pequot Press. ISBN 9780762766321. OCLC 841515030.

Further reading

- Lewis, Emanuel Raymond (1979). Seacoast Fortifications of the United States. Annapolis: Leeward Publications. ISBN 978-0-929521-11-4.

- Weaver II, John R. (2018). A Legacy in Brick and Stone: American Coastal Defense Forts of the Third System, 1816-1867, 2nd Ed. McLean, VA: Redoubt Press. ISBN 978-1-7323916-1-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Fort Pickens. |