University of Mississippi

The University of Mississippi (colloquially known as Ole Miss) is a public research university in Oxford, Mississippi. Including the University of Mississippi Medical Center in Jackson, it is the state's largest university by enrollment[5] and promotes itself as the state’s flagship university.[6][7] The university was chartered by the Mississippi Legislature on February 24, 1844, and four years later admitted its first enrollment of 80 students. The university is classified among "R1: Doctoral Universities – Very high research activity".[8][9] According to the National Science Foundation, Ole Miss spent $137 million on research and development in 2018, ranking it 142nd in the nation.[10]

| |

| Motto | Pro scientia et sapientia (Latin) |

|---|---|

Motto in English | For knowledge and wisdom |

| Type | Public Flagship Sea-grant Space-grant |

| Established | 1848 |

Academic affiliations | ORAU APLU SURA |

| Endowment | $736.3 million (2019)[1] |

| Budget | $2.448 billion (2016)[2] |

| Chancellor | Glenn Boyce |

| Vice-Chancellor | Katrina Caldwell |

| Provost | Noel E. Wilkin |

Academic staff | 871 |

| Students | 23,258 (fall 2017)[3] |

| Location | , , United States 34.365°N 89.538°W |

| Campus | Rural (small college town) 2,000+ acres |

| Colors | Cardinal red and Navy blue[4] |

| Nickname | Rebels |

Sporting affiliations | NCAA Division I FBS – SEC |

| Website | www |

| |

Across all its campuses, the university comprises some 23,258 students.[3] In addition to the main campus in Oxford and the medical school in Jackson, the university also has campuses in Tupelo, Booneville, Grenada, and Southaven, as well as an accredited online high school.[11][12] About 55 percent of its undergraduates and 60 percent overall come from Mississippi, and 23 percent are minorities; international students respectively represent 90 different nations.[13] It is one of the 33 colleges and universities participating in the National Sea Grant Program and a participant in the National Space Grant College and Fellowship Program.[14]

Ole Miss was a center of activity during the American civil rights movement when a race riot erupted in 1962 following the attempted admission of James Meredith, an African-American, to the segregated campus.[15] Although the university was integrated that year, the use of Confederate symbols and motifs has remained a controversial aspect of the school's identity and culture.[16][17][18][19][20] In response the university has taken measures to rebrand its image, including effectively banning the display of Confederate flags in Vaught-Hemingway Stadium in 1997, officially abandoning the Colonel Reb mascot in 2003, and removing "Dixie" from the Pride of the South marching band's repertoire in 2016.[21][22][23] In 2018, following a racially charged rant on social media by an alumnus and academic building namesake, former Chancellor Jeffrey Vitter reaffirmed the university's commitment to "honest and open dialogue about its history", and in making its campuses "more welcoming and inclusive".[24]

History

Founding, expansion, and tradition

.jpg)

The Mississippi Legislature chartered the University of Mississippi on February 24, 1844. The university opened its doors to its first class of 80 students four years later in 1848. For 23 years, the university was Mississippi's only public institution of higher learning, and for 110 years it was the state's only comprehensive university.[26] Politician Pryor Lea was a founding trustee.[27]

When the university opened, the campus consisted of six buildings: two dormitories, two faculty houses, a steward's hall, and the Lyceum at the center. Constructed from 1846 to 1848, the Lyceum is the oldest building on campus. Originally, the Lyceum housed all of the classrooms and faculty offices of the university. The building's north and south wings were added in 1903, and the Class of 1927 donated the clock above the eastern portico. The Lyceum is now the home of the university's administration offices. The columned facade of the Lyceum is represented on the official crest of the university, along with the date of establishment.[28]

In 1854, the university established the fourth state-supported, public law school in the United States, and also began offering engineering education.[29]

With the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861, classes were interrupted and almost the entire student body (135 out of 139 students) enlisted in Company A of the 11th Mississippi regiment of the Confederate army.[30] This company, nicknamed the University Greys, suffered a 100% casualty rate in Pickett's Charge.[30]

The Lyceum was used as a hospital during the Civil War for both Union and Confederate soldiers, especially those who were wounded at the battle of Shiloh. Two hundred-fifty soldiers who died in the campus hospital were buried in a cemetery on the grounds of the university.[31][32]

During the post-war period, the university was led by former Confederate general A.P. Stewart, a Rogersville, Tennessee native. He served as Chancellor from 1874 to 1886.[33]

The university became coeducational in 1882 and was the first such institution in the Southeast to hire a female faculty member, Sarah McGehee Isom, doing so in 1885.[34]

The student yearbook was published for the first time in 1897. A contest was held to solicit suggestions for a yearbook title from the student body. Elma Meek, a student, submitted the winning entry of "Ole Miss." Meek's source for the term is unknown; some historians theorize she made a diminutive of "old Mississippi" or derived the term from "ol' missus," an African-American term for a plantation's "old mistress.[35][36][37][38] This sobriquet was not only chosen for the yearbook, but also became the name by which the university was informally known.[39] "Ole Miss" is defined as the school's intangible spirit, which is separate from the tangible aspects of the university.[40][41]

The university began medical education in 1903, when the University of Mississippi School of Medicine was established on the Oxford campus. In that era, the university provided two-year pre-clinical education certificates, and graduates went out of state to complete doctor of medicine degrees. In 1950, the Mississippi Legislature voted to create a four-year medical school. On July 1, 1955, the University Medical Center opened in the capital of Jackson, Mississippi, as a four-year medical school. The University of Mississippi Medical Center, as it is now called, is the health sciences campus of the University of Mississippi. It houses the University of Mississippi School of Medicine along with five other health science schools: nursing, dentistry, health-related professions, graduate studies and pharmacy (The School of Pharmacy is split between the Oxford and University of Mississippi Medical Center campuses).[42]

Several attempts were made via the executive and legislative branches of the Mississippi state government to relocate or otherwise close the University of Mississippi. The Mississippi Legislature between 1900 and 1930 introduced several bills aiming to accomplish this, but no legislation was ever passed by either house. One such bill was introduced in 1912 by Senator William Ellis of Carthage, Mississippi, which would have merged the college with then-Mississippi A&M.[43] However, this measure was soundly defeated, despite the bill only seeking to form an exploratory committee.

In February 1920, 56 members of the legislature arrived on campus and discussed with students and faculty the idea of consolidating MS A&M, MS College of Women and Ole Miss to be in Jackson, rather than appropriate $750,000.00 of funds requested by then-Chancellor Joseph Powers which were needed to repair dilapidated and structurally unsound buildings on the campus, which was discovered following the partial collapse of a dormitory in 1917 and a scathing review of other buildings later that same year by the state architect.[44] These funds, plus an additional $300,000.00 were appropriated to the school, which was used to build 4 male dormitories, a female dormitory and a pharmacy building, which partially resolved a longstanding issue of inadequate dormitory space for students. During the 1930s, Mississippi Governor Theodore G. Bilbo, a populist, tried to move the university to Jackson. Chancellor Alfred Hume gave the state legislators a grand tour of Ole Miss and the surrounding historic city of Oxford, persuading them to keep it in its original setting.

During World War II, UM was one of 131 colleges and universities nationally that took part in the V-12 Navy College Training Program, which offered students a path to a Navy commission.[45]

Integration of 1962 and legacy

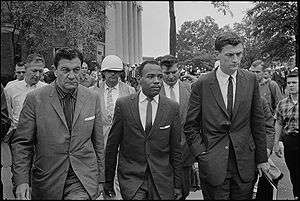

Desegregation came to Ole Miss in the early 1960s with the activities of United States Air Force veteran James Meredith from Kosciusko, Mississippi. Even Meredith's initial efforts required great courage. All involved knew how William David McCain and the white political establishment of Mississippi had recently reacted to similar efforts by Clyde Kennard to enroll at Mississippi Southern College (now the University of Southern Mississippi).[46][47][48][49]

Meredith won a lawsuit that allowed him admission to the University of Mississippi in September 1962. He attempted to enter campus on September 20, September 25, and again on September 26,[50] only to be blocked by Mississippi Governor Ross R. Barnett, who proclaimed "...No school in our state will be integrated while I am your Governor. I shall do everything in my power to prevent integration in our schools."[51]

After the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit held both Barnett and Lieutenant Governor Paul B. Johnson, Jr. in contempt, with fines of more than $10,000 for each day they refused to allow Meredith to enroll,[52] President John F. Kennedy dispatched 127 U.S. Marshals, 316 deputized U.S. Border Patrol agents, and 97 federalized Federal Bureau of Prisons personnel to escort Meredith to the campus on September 30, 1962.[53][54]

Two civilians were killed by gunfire during the riot, French journalist Paul Guihard and Oxford repairman Ray Gunter.[55][56] Eventually, 3,000 United States Army and federalized Mississippi National Guard troops quickly arrived in Oxford that helped quell the riot and brought the situation under control.[57] One-third of the federal officers, 166 men, were injured, as were 40 federal soldiers and National Guardsmen.[58]

After control was re-established by federal-led forces, Meredith was able to enroll and attend his first class on October 1. Following the riot, Army and National Guard troops were stationed in Oxford to prevent future similar violence. While most Ole Miss students did not riot prior to his enrollment in the university, many harassed Meredith during his first two semesters on campus.[59]

According to first-person accounts, students living in Meredith's dorm bounced basketballs on the floor just above his room through all hours of the night. When Meredith walked into the cafeteria for meals, the students eating would all turn their backs. If Meredith sat at a table with other students, all of whom were white, they would immediately move to another table.[59] Many of these events are featured in the 2012 ESPN documentary film Ghosts of Ole Miss.

Historical observations and remembrances

In 2002 the university marked the 40th anniversary of integration with a yearlong series of events titled "Open Doors: Building on 40 Years of Opportunity in Higher Education." These included an oral history of Ole Miss, various symposiums, the April unveiling of a $130,000 memorial, and a reunion of federal marshals who had served at the campus. In September 2003, the university completed the year's events with an international conference on race. By that year, 13% of the student body identified as African American. Meredith's son Joseph graduated as the top doctoral student at the School of Business Administration.[60]

Six years later, in 2008, the site of the riots, known as Lyceum-The Circle Historic District, was designated as a National Historic Landmark.[61] The district includes:

- The Lyceum

- The Circle, including the flagpole

- Croft Institute for International Studies, also known as the "Y" Building

- Brevard Hall, also known as the "Old Chemistry" Building

- Carrier Hall

- Shoemaker Hall

- Ventress Hall

- Bryant Hall

- Peabody Hall

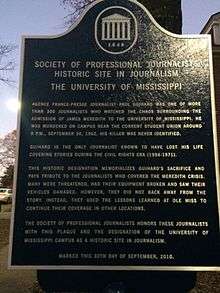

Additionally, on April 14, 2010, the university campus was declared a National Historic Site by the Society of Professional Journalists to honor reporters who covered the 1962 riot, including the late French reporter Paul Guihard, a victim of the riot.[62]

From September 2012 to May 2013, the university marked its 50th anniversary of integration with a program called Opening the Closed Society, referring to Mississippi: The Closed Society, a 1964 book by James W. Silver, a history professor at the university.[63] The events included lectures by figures such as Attorney General Eric H. Holder Jr. and the singer and activist Harry Belafonte, movie screenings, panel discussions, and a "walk of reconciliation and redemption."[64] Myrlie Evers-Williams, widow of Medgar Evers, slain civil rights leader and late president of the state NAACP, closed the observance on May 11, 2013, by delivering the address at the university's 160th commencement.[65][65]

Recent history

The university was chosen to host the first presidential debate of 2008, between Senator John McCain and then-Senator Barack Obama which was held September 26, 2008. This was the first presidential debate to be held in Mississippi.[66][67]

The university adopted a new on-field mascot for athletic events in the fall of 2010.[68] Colonel Reb, retired from the sidelines of sporting events in 2003, was officially replaced by "Rebel", a black bear, and then, in 2018, was replaced by The Landshark.[69] All university sports teams are still officially referred to as the Rebels.[70]

The university's 25th Rhodes Scholar was named in 2008. Since 1998, it has produced two Rhodes Scholars, as well as 10 Goldwater Scholars, seven Truman Scholars, 18 Fulbright Scholars, a Marshall Scholar, three Udall Scholars, two Gates Cambridge Scholars, one Mitchell Scholar, 19 Boren Scholars, one Boren fellow and one German Chancellor Fellowship.[71]

In 2015, "Students Against Social Injustice" (SASI) started a movement to remove Confederate iconography from the campus, such as the Mississippi State Flag (which showed the Confederate flag).[72] The university stopped flying the flag in 2019. In 2018, SASI asked that the Confederate Monument located at The Center be removed from campus.[73] In 2019, during Black History Month, student activists marched twice to support moving the monument. In March 2019, the Faculty Senate, Graduate Student Council, and the Associated Student Body voted to relocate the monument,[74][75] and in June 2020, the university relocated the Confederate Monument to the University Cemetery.[76]

Academics

The student-faculty ratio at University of Mississippi is 19:1, and the school has 47.4 percent of its classes with fewer than 20 students. The most popular majors at University of Mississippi include: Integrated Marketing Communications, Elementary Education and Teaching; Marketing/Marketing Management, General; Accountancy, Finance, General; Pharmacy, Pharmaceutical Sciences, and Administration, Other; Biology, Psychology and Criminal Justice; and Business Administration and Management, General. The average freshman retention rate, an indicator of student success and satisfaction, is 85.3 percent.[77]

Divisions of the university

The degree-granting divisions at the main campus in Oxford are:

- School of Accountancy

- School of Applied Sciences

- School of Business Administration

- School of Education

- School of Engineering

- College of Liberal Arts

- Graduate School

- School of Law

- School of Pharmacy

- School of Journalism and New Media

- General Studies Program

The schools at the University of Mississippi Medical Center campus in Jackson are:

- School of Dentistry

- School of Health Related Professions

- School of Nursing (with a satellite unit at the main campus)

- School of Medicine

- School of Graduate Studies in the Health Sciences

- School of Population Health

University of Mississippi Medical Center surgeons, led by James Hardy, performed the world's first human lung transplant, in 1963, and the world's first animal-to-human heart transplant, in 1964. The heart of a chimpanzee was used for the heart transplant because of Hardy's research on transplantation, consisting of primate studies during the previous nine years.[78][79]

The University of Mississippi Field Station in Abbeville is a natural laboratory used to study, research and teach about sustainable freshwater ecosystems.

Since 1968, the school operates the only legal marijuana farm and production facility in the United States. The National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) contracts to the university the production of cannabis for use in approved research studies on the plant as well as for distribution to the seven surviving medical cannabis patients grandfathered into the Compassionate Investigational New Drug program (established in 1978 and canceled in 1991).[80]

The university houses one of the largest blues music archives in the United States. Some of the contributions to the collection were donated by BB King who donated his personal record collection. The archive includes the first ever commercial blues recording, a song called "Crazy Blues" recorded by Mamie Smith in 1920.[81] The Mamie and Ellis Nassour Arts & Entertainment Collection, highlighted by a wealth of theater and film scripts, photographs and memorabilia, was dedicated in September 2005.

Special programs

Center for Intelligence and Security Studies

The Center for Intelligence and Security Studies (CISS) delivers academic programming to prepare outstanding students for careers in intelligence analysis in both the public and private sectors. In addition, CISS personnel engage in applied research and consortium building with government, private and academic partners. In late 2012, the United States Director of National Intelligence designated CISS as an Intelligence Community Center of Academic Excellence (CAE). CISS is one of only 29 college programs in the United States with this distinction.[82]

Center for Manufacturing Excellence

The Haley Barbour Center for Manufacturing Excellence[83] (CME) was established in June 2008.

Chinese Language Flagship Program

The university offers the Chinese Language Flagship Program (simplified Chinese: 中文旗舰项目; traditional Chinese: 中文旗艦項目; pinyin: Zhōngwén Qíjiàn Xiàngmù), a study program aiming to provide Americans with an advanced knowledge of Chinese.[84]

Croft Institute for International Studies

The Croft Institute for International Studies at the University of Mississippi is a privately funded, select-admissions, undergraduate program for high achieving students who pursue a B.A. degree in international studies. Croft students combine a regional concentration in Europe, East Asia, Latin America, or the Middle East with a thematic concentration in global economics and business, international governance and politics, global health or social and cultural identity.

International Student Organization

The University of Mississippi has several student organizations. One organization is the International Student Organization (ISO), which organizes activities and events for international students. Notable events of the ISO include a cultural night, date auction and international sports tournament.

Lott Leadership Institute

Named in honor of distinguished Ole Miss alumnus, former U.S. Sen. Trent Lott, the Lott Leadership Institute[85] offers a wide range of leadership and outreach programs that work to enrich the lives and enhance the abilities of students and faculty, as well as high school students, students from other colleges and universities, and the community.

Mississippi Excellence in Teaching Program

UM is a collaborator in the Mississippi Excellence in Teaching Program,[86] designed to attract top students to teacher education programs with full scholarships and professional incentives. The goal is to attract the top high school seniors who want to become mathematics and English teachers in Mississippi. Funded by the Robert M. Hearin Support Foundation, the program is designed to create a unique “honors college style” learning experience for high-performing education students and promote collaboration between students and faculty at UM and Mississippi State University.

The World Class Teaching Program

The World Class Teaching Program is a special program at the University of Mississippi School of Education designed to provide support to teachers going through the National Board Certification process.[87]

Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College

The Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College[88] attracts a diverse body of high-performing students to the University of Mississippi and prepares citizen scholars who are fired by the life of the mind, committed to the public good and driven to find solutions. Established in 1997 through a gift from the Jim Barksdale family, the Honors College merges intellectual rigor with community action. It offers an education similar to that at prestigious private liberal arts schools and universities, but at a far lower cost. Small, discussion-based classes, dedicated faculty and a nurturing staff enable honors students to experience intellectual as well as personal growth.

SECU: SEC Academic Initiative

The University of Mississippi is a member of the SEC Academic Consortium. Now renamed the SECU, the initiative was a collaborative endeavor designed to promote research, scholarship and achievement among the member universities in the Southeastern Conference. The SECU formed to serve as a means to bolster collaborative academic endeavors of Southeastern Conference universities. Its goals include highlighting the endeavors and achievements of SEC faculty, students and its universities and advancing the academic reputation of SEC universities.[89][90]

In 2013, the University of Mississippi participated in the SEC Symposium in Atlanta, Georgia which was organized and led by the University of Georgia and the UGA Bioenergy Systems Research Institute. The topic of the symposium was titled "Impact of the Southeast in the World's Renewable Energy Future."[91]

Writing Center

The university offers students assistance with writing through the Department of Writing and Rhetoric. The department's writing center functions out of Lamar Hall, and the center employs undergraduate students who are certified through the College Reading & Learning Association as tutors and consultants.

Rankings and accolades

| University rankings | |

|---|---|

| National | |

| ARWU[92] | 182–192 |

| Forbes[93] | 401 |

| THE/WSJ[94] | 311 |

| U.S. News & World Report[95] | 162 |

| Washington Monthly[96] | 273 |

| Global | |

| ARWU[97] | 801–900 |

| QS[98] | 801–1000 |

| U.S. News & World Report[99] | 364 |

For the last 10 years, the Chronicle of Higher Education named the University of Mississippi as one of the "Great Colleges to Work For", putting the institution in elite company. The 2018 results, released in the Chronicle's annual report on "The Academic Workplace", Ole Miss was among 84 institutions honored from the 253 colleges and universities surveyed.[100] In 2018, the Ole Miss campus was ranked the second safest in the SEC and one of the safest in nation.[101] U.S. News & World Report ranks the Professional MBA program at the UM School of Business Administration in the top 50 among American public universities, and the online MBA program ranks in the top 25.[102][103] All three degree programs at the University of Mississippi's Patterson School of Accountancy are among the top 10 in the 2018 annual national rankings of accounting programs published by the journal Public Accounting Report. The undergraduate and doctoral programs are No. 7, while the master's program is No. 9. The undergraduate and doctoral programs lead the Southeastern Conference in the rankings, and the master's program is second in the SEC. One or more Ole Miss programs have led the SEC in each of the past eight years.[104]

The Army ROTC program received one of eight prestigious MacArthur Awards in February 2012. Presented by the U.S. Army Cadet Command and the Gen. Douglas MacArthur Foundation, the award recognizes the ideals of "duty, honor and country" as advocated by MacArthur. For its life-changing work in 12 Delta communities, the UM School of Pharmacy won the American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy's 2011–12 Lawrence C. Weaver Transformative Community Service Award. AACP presents the award annually to one pharmacy school that not only shows a major commitment to addressing unmet community needs through education, practice and research but also serves as an example of social responsiveness for others. Ole Miss continues to be the premiere destination for college tailgating as the Grove claimed second place in Southern Living's "South's Best Tailgate" contest in 2012. The William Winter Institute for Racial Reconciliation at the University of Mississippi was honored by the International Association of Official Human Rights Agencies with its 2012 International Award. This accolade from the nonprofit organization devoted to promoting civil and human rights around the world was presented in New Orleans.[105]

Campus

The University of Mississippi's main campus is in Oxford. There are also regional campuses in Booneville, DeSoto, Grenada, and Tupelo.

The University of Mississippi in Oxford is the original campus, beginning with only one square-mile of land.[106] The main campus today contains around 1,200 acres of land (1.875 square-miles). Also, the University of Mississippi owns a golf course and airport in Oxford.[106] The golf course and airport are also considered part of the University of Mississippi, Oxford campus.

The buildings on the main University of Mississippi campus come from the Georgian age of architecture; however, some of the newer buildings today have a more contemporary architecture.[106] The first building built on the Oxford campus is the Lyceum, and is the only original building remaining.[106] The construction of the Lyceum began in 1846 and was completed in 1848.[106] The Lyceum served as a hospital to soldiers in the Civil War.[107] Also on the campus, the Croft Institute for International Studies and Barnard Observatory were used for soldiers during the civil war.[107] The Oxford campus of the University of Mississippi contains a lot of history with the Civil War. The campus was used as a hospital, but also after soldiers died, the campus served as a morgue. Where Farley Hall is now, the prior building was referred to as the "Dead House" where the bodies of deceased soldiers were stored.[108]

Architect Frank P. Gates designed 18 buildings on campus in 1929-1930, mostly in the Georgian Revival architectural style, including (Old) University High School, Barr Hall, Bondurant Hall, Farley Hall (also known as Lamar Hall), Faulkner Hall, Hill Hall, Howry Hall, Isom Hall, Longstreet Hall, Martindale Hall, Vardaman Hall, the Cafeteria/Union Building, and the Wesley Knight Field House.[109][110]

Today on the University of Mississippi campus, most of the buildings have been completely renovated or newly constructed. There are currently at least 15 residential buildings on the Oxford campus, with more being built.[106] The Oxford campus is also home to eleven sorority houses and fourteen fraternity houses.[106] The chancellor of The University of Mississippi also lives on the edge of campus.[106]

The University of Mississippi campus in Oxford is known for the beauty of the campus. The campus has been recognized multiple years, but most recently, in 2016, USA Today recognized Ole Miss as the "Most Beautiful Campus".[111] The campus grounds are kept up through the University of Mississippi's personal landscape service.[111]

The University of Mississippi's satellite campuses are much smaller than the Oxford campus. The satellite campus in Tupelo started running in a larger space in 1972,[112] the DeSoto campus opened in 1996,[113] and the Grenada campus has been operated on the Holmes Community College campus since 2008.[114] The University of Mississippi campus and satellite campuses continue to grow. There will continue to be progress in construction to accommodate for the large growth in student population.

Athletics

The University of Mississippi participates in the National Collegiate Athletic Association, Southeastern Conference, Division I.

Varsity athletic teams at the University of Mississippi are offered for women in the sports of basketball, cross country, golf, rifle (this sport is sponsored by the Great America Rifle Conference, a special conference within the NCAA), soccer, softball, tennis, track & field, and volleyball. Men's varsity teams are offered in baseball, basketball, cross country, football, golf, tennis, and track & field.[115]

The University of Mississippi athletic teams have collected numerous championships including:

- Tennis - Five overall SEC championships (1996, 1997, 2004, 2005, 2009) and one NCAA Singles Champion, Devin Britton.

- Track & Field - Brittney Reese won the NCAA indoor and outdoor long jump title in 2008, and went on to the 2008 Beijing Olympic Games. Barnabas Kirui won the 2006 SEC Cross Country Championship and won four SEC titles in the 5000 and 10,000 meter races, and two 3000 meter steeplechase championships. Antwon Hicks won the NCAA Indoor Championship in 60-meter hurdles twice (2000, 2001).

- Baseball - SEC overall championship 2009.[116]

- Football - Six SEC championships (1947, 1954, 1955, 1960, 1962, 1963), 1960 National Champion.[117]

Famous football alumni Archie and Eli Manning are honored on the University of Mississippi campus with speed limits set to 18 and 10 MPH: their jersey numbers, respectively.[118][119]

Ross Bjork is one of the university's past athletics directors.[120]

Student life

There are hundreds of students organizations, including 25 religious organizations.[121]

Student media

- The Daily Mississippian (DM) is the student-published newspaper of the university, established in 1911. Although it is on the Ole Miss campus, it is operated largely as an independent newspaper run by students. The DM is the only college newspaper in the state published five times a week. The staff consists of approximately 15 editors, about 25 writers and photographers, and a five-person student sales staff. Daily circulation is 12,000. The award-winning publication celebrated its 100th anniversary in 2011–12.

- TheDMonline.com is the online version of The Daily Mississippian and also includes original content that supplements the print publication - photo galleries, videos, breaking news and student blogs. Page views average up to 360,000 a month.

- The Ole Miss student yearbook is a 368-page full-color book produced by students. It has won many awards, including a Gold Crown.[122]

- WUMS-FM 92.1 Rebel Radio, is a FCC commercially licensed radio station. It is one of only a few student-run, commercially licensed radio stations in the nation, with a signal stretching about 60 miles across North Mississippi. Its format features Top 40, alternative and college rock, news and talk shows.

- NewsWatch is a student-produced, live newscast, and the only local newscast in Lafayette County. Broadcast through the Metrocast cable company, it is live at 5 p.m. Monday-Friday, and livestreamed on newswatcholemiss.com.

These publications and broadcasts are part of the S. Gale Denley Student Media Center at Ole Miss.

Student housing

Approximately 5,300 students live on campus in 13 residence halls, two residential colleges and two apartment complexes.[123] All freshmen (students with less than 30 credit hours) are required to live in campus housing their first year unless they meet certain commuter guidelines.[124] The Department of Student Housing is an auxiliary, meaning it is self-supporting and does not receive appropriations from state funds. All rent received from students pays for housing functions such as utilities, staff salaries, furniture, supplies, repairs, renovations and new buildings.[125] Most of the residence staff members are students, including day-to-day management, conduct board members and maintenance personnel.[126] Upon acceptance to the University of Mississippi, a housing application is submitted with an application fee.[126] The cost of on-campus housing ranges from approximately $4,000 to more than $8,000 (the highest price being that of the newly renovated Village apartments) per academic or calendar year, depending on the occupancy and room type.[126] Students (with more than 30 credit hours) can live off campus in unaffiliated housing.[126]

| Residence hall | Year built / renovation | Type |

|---|---|---|

| Brown | Built 1961 / renovated NA | Traditional |

| Burns | Built 2011 / renovated NA | Contemporary |

| Crosby | Built 1971 / renovated NA | Traditional |

| Campus Walk | Built 2001 / renovated NA | Apartment |

| Deaton | Built 1952 / renovated 2001 | Traditional |

| Hefley | Built 1959 / renovated 2001 | Traditional |

| Kincannon | Closed fall 2016 | Traditional |

| Luckyday Residential College | Built 2010 / renovated NA | Contemporary |

| Martin | Built 1969 / renovated NA | Traditional |

| Minor | Built 2011 / renovated NA | Contemporary |

| Northgate | Built 1950s / renovated unknown | Apartment |

| Pittman | Built 2011 / renovated NA | Contemporary |

| Residential Hall 1 | Built 2015 / renovated NA | Contemporary |

| Residential Hall 2 | Built 2016 / renovated NA | Contemporary |

| Residential Hall 3 | Built 2016 / renovated NA | Contemporary |

| Residential College South | Built 2009 / renovated NA | Contemporary |

| Stewart | Built 1963 / renovated NA | Traditional |

| Stockard | Built 1969 / renovated NA | Traditional |

Graduate students, undergraduate students aged 25 or older, students who are married, and students with families may live in the Village Apartments. The complex consists of six two story buildings, and is adjacent to the University of Mississippi Law School. Undergraduates over 25, married students, and graduate students may live in the one-bedroom apartments. Graduate students and students over 25 may live in studio style apartments. Students with children may live in the two-bedroom apartments.[127] Children living in the Village Apartments are zoned to the Oxford School District.[128] Residents are zoned to Bramlett Elementary School (PreK-1), Oxford Elementary School (2-3), Della Davidson Elementary School (4-5), Oxford Middle School (6-8), and Oxford High School (9-12).[129]

Greek life

Despite the relatively small number of Greek-letter organizations on campus, a third of all undergraduates participate in Greek life at Ole Miss. The tradition of Greek life on the Oxford campus is a deep-seated one. In fact, the first fraternity founded in the South was the Rainbow Fraternity, founded at Ole Miss in 1848. The fraternity merged with Delta Tau Delta in 1886.[130] Delta Kappa Epsilon followed shortly after at Ole Miss in 1850, as the first to have a house on campus in Mississippi. Delta Gamma Women's Fraternity was founded in 1873 at the Lewis School for Girls in nearby Oxford. All Greek life at Ole Miss was suspended from 1912 to 1926 due to statewide anti-fraternity legislation.[131]

Today, sorority chapters are very large, with some boasting over 400 active members. Recruitment is fiercely competitive and potential sorority members are encouraged to secure personal recommendations from Ole Miss sorority alumnae to increase the chances of receiving an invitation to join one of the eleven NPC sororities on campus. Fraternity recruitment is also fierce, with only 14 active IFC chapters on campus.

Inactive chapters:

|

Inactive chapters:

|

|

Associated Student Body

The Associated Student Body (ASB) is the Ole Miss student government organization. Students are elected to the ASB Senate in the spring semester, with leftover seats voted on in the fall by open-seat elections. Senators can represent RSOs (Registered-Student Organizations) such as the Greek councils and sports clubs, or they can run to represent their academic school (i.e., College of Liberal Arts or School of Engineering).[133] The ASB officers are also elected in the spring semester, following two weeks of campaigning.[134] Following the elections, newly sworn-in ASB officers release applications, conduct interviews, and eventually choose their cabinet members for the coming school year.[134] The student body, excluding the Medical Center, includes 18,121 undergraduates, 2,089 graduate students, 357 law students and 323 students in the Doctor of Pharmacy program. African-Americans comprise 12.8 percent of the student body.[135]

Notable alumni

- Notable people

.jpg)

.jpg)

_(Miss_America%2C_'58-'59%2C)_(Photo_at_WLBT)..png)

See also

- Mississippi Teacher Corps – based at the university

- Insight Park

Further reading

- Mangan, Katherine (June 25, 2015). "Removing Confederate Symbols Is a Step, but Changing a Campus Culture Can Take Years". Chronicle of Higher Education.

- Nick, Bryant (Autumn 2006). "Black Man Who Was Crazy Enough to Apply to Ole Miss". Journal of Blacks in Higher Education. 53. pp. 60–71.

References

- As of June 30, 2019. "U.S. and Canadian 2019 NTSE Participating Institutions Listed by Fiscal Year 2019 Endowment Market Value, and Percentage Change in Market Value from FY18 to FY19 (Revised)". National Association of College and University Business Officers and TIAA. Retrieved April 18, 2020.

- "About UM: Facts - University of Mississippi". The University of Mississippi Facts & Statistics.

- Ole Miss News. "UM Welcomes New and Returning Students for Fall Semester".

- "Licensing FAQ's". Department of Licensing – University of Mississippi. Archived from the original on July 6, 2016. Retrieved July 11, 2016.

- Box 1848, The University of Mississippi P. O.; University; Usa915-7211, Ms 38677. "fall-2017-2018-enrollment". Office of Institutional Research, Effectiveness, and Planning. Retrieved May 21, 2019.

- "Tuition and Fees at Flagship Universities over Time - Trends in Higher Education - The College Board". trends.collegeboard.org. Retrieved May 21, 2019.

- "About UM: University of Mississippi". olemiss.edu. Retrieved May 21, 2019.

- "Carnegie Classifications Institution Lookup". carnegieclassifications.iu.edu. Center for Postsecondary Education. Retrieved July 25, 2020.

- "In new sorting of colleges, Dartmouth falls out of an exclusive group". Washington Post. February 4, 2016. Retrieved June 9, 2018.

- "Table 20. Higher education R&D expenditures, ranked by FY 2018 R&D expenditures: FYs 2009–18". ncsesdata.nsf.gov. National Science Foundation. Retrieved July 25, 2020.

- "The University of Mississippi Regional Campuses". www.outreach.olemiss.edu. Retrieved June 27, 2018.

- "The University of Mississippi Division of Outreach and Continuing Education - UM High School". www.outreach.olemiss.edu. Archived from the original on April 18, 2019. Retrieved April 24, 2019.

- "The University of Mississippi Facts and Statistics". University of Mississippi. January 15, 2016.

- "National Space Grant College and Fellowship Program". NASA. July 28, 2015. Retrieved June 9, 2018.

- "Integrating Ole Miss: A Transformative, Deadly Riot". NPR.org. Retrieved July 9, 2018.

- "Ole Miss Edges Out of Its Confederate Shadow, Gingerly". Retrieved July 9, 2018.

- "'Ole Miss' Debates Campus Traditions With Confederate Roots". NPR.org. Retrieved July 9, 2018.

- "The Confederacy still haunts the campus of Ole Miss". NBC News. Retrieved July 9, 2018.

- "Ole Miss to change building name, add plaques to give Confederate context". WREG.com. August 16, 2017. Retrieved July 9, 2018.

- "ESPN.com - Page2 - Mississippi's mascot mess". a.espncdn.com. Retrieved July 9, 2018.

- "CNN - Flag ban tugs on Ole Miss traditions - October 25, 1997". www.cnn.com. Retrieved July 9, 2018.

- Brown, Robbie. "Ole Miss Shelves Mascot Fraught With Baggage". Retrieved July 9, 2018.

- "Ole Miss is Without a Mascot". Archived from the original on July 9, 2018. Retrieved July 9, 2018.

- Ryback, Timothy W. (September 19, 2017). "What Ole Miss Can Teach Universities About Grappling With Their Pasts". The Atlantic. Retrieved June 12, 2018.

- Steube, Christina (October 31, 2014). "Some Older Areas of Campus Have a Spooky Past". The University of Mississippi.

- "The University of Mississippi - History". Olemiss.edu. Archived from the original on April 4, 2013. Retrieved December 14, 2012.

- "National Register of Historic Places Inventory/Nomination: Lea Springs". National Park Service. Retrieved June 14, 2018. With accompanying pictures

- "Virtual Tours - The University of Mississippi". Olemiss.edu. October 1, 2006. Retrieved December 14, 2012.

- "School of Engineering • About Us". Engineering.olemiss.edu. Archived from the original on January 25, 2013. Retrieved December 14, 2012.

- "Civil War Casualties". Archived from the original on April 10, 2016. Retrieved April 30, 2016.

- "Confederate Cemetery - About - Google". Maps.google.com. Retrieved December 14, 2012.

- "The Center for Civil War Research". Retrieved May 29, 2015.

- "2010 Chancellor's Inauguration - The University of Mississippi". Olemiss.edu. Archived from the original on December 2, 2012. Retrieved December 14, 2012.

- "Sarah Isom Center for Women". Olemiss.edu. Archived from the original on August 18, 2011. Retrieved December 14, 2012.

- Cabaniss, J. A. (1949). The University of Mississippi; Its first hundred years. University & College Press Of Mississippi. ISBN 978-0-87805-000-0.p. 129

- https://www.chronicle.com/interactives/11082019-OleMiss?cid=at&source=ams&sourceId=5058459

- Eagles, Charles (2009). The Price of Defiance: James Meredith and the Integration of Ole Miss. The University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-3273-8.p. 17

- Sansing, David (1999). The University of Mississippi: A Sesquicentennial History. University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 978-1-57806-091-7. p. 168

- The Ole Miss Student Yearbook Archived October 1, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- Everett, Frank E. (1962). Frank E. Everett Collection (MUM00123). The Department of Archives and Special Collections, J.D. Williams Library, The University of Mississippi.

- "OLE MISS Official Athletic Site - Traditions". Olemisssports.Com. Archived from the original on June 30, 2016. Retrieved December 14, 2012.

- "Overview - University of Mississippi Medical Center". Umc.edu. November 3, 2011. Archived from the original on February 22, 2012. Retrieved December 14, 2012.

- David Sansing, The History of the University of Mississippi: A Sesquicentennial History, Ch. 8

- David Sansing, The History of the University of Mississippi: A Sesquicentennial History, Ch. *

- "U.S. Naval Administration in World War II". HyperWar Foundation. 2011. Retrieved September 29, 2011.

- The Funding of Scientific Racism: Wickliffe Draper and the Pioneer Fund by William H. Tucker, University of Illinois Press (May 30, 2007), pp 165-66.

- Hague, Euan; Beirich, Heidi; Sebesta, Edward H., eds. (2008). Neo-Confederacy: A Critical Introduction. University of Texas Press. pp. 284–285. ISBN 978-0-2927-7921-1.

- "Sons of Confederate Veterans in its own Civil War | Southern Poverty Law Center". Splcenter.org. Retrieved December 14, 2012.

- Medgar Evers by Jennie Brown, Holloway House Publishing, 1994, pp. 128-132.

- Archived November 12, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- "Ross Barnett, Segregationist, Dies; Governor of Mississippi in 1960's". The New York Times. November 7, 1987. Retrieved May 27, 2010.

- "U.S. Marshals Mark 50th Anniversary of the Integration of 'Ole Miss'". Archived from the original on May 23, 2020. Retrieved April 24, 2020.

- Archived July 6, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- Doyle, William (2001). An American Insurrection. New York, NY: Doubleday. p. 215. ISBN 978-0385499699.

- Riches, William T. Martin. The Civil Rights Movement: Struggle and Resistance. Palgrave Macmillan, 2004.

- "Riots over desegregation of Ole Miss". History. February 9, 2010.

- "The States: Though the Heavens Fall". TIME. October 12, 1962. Retrieved October 3, 2007.

- The band played Dixie: Race and the liberal conscience at Ole Miss, Nadine Cohodas, (1997), New York, Free Press

- Shelia Hardwell Byrd (September 21, 2002). "Meredith ready to move on". Associated Press, at Athens Banner-Herald (OnlineAthens). Archived from the original on October 16, 2007. Retrieved October 2, 2007.

- Gene Ford and Susan Cianci Salvatore (January 23, 2007). National Historic Landmark Nomination: Lyceum (PDF). National Park Service. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 26, 2009.

- Jerry Mitchell (April 14, 2010). "Ole Miss declared National Historic Site". The Clarion-Ledger. Archived from the original on January 19, 2013. Retrieved April 14, 2010.

- Robertson, Campbell (September 30, 2012). "University of Mississippi Commemorates Integration". The New York Times.

- Calendar Set for 50 Years of Integration at Ole Miss. News.olemiss.edu (September 25, 2012). Retrieved on August 17, 2013.

- Mitchell, Jerry (May 11, 2013). "Ole Miss honors Evers-Williams". Clarion Ledger. Retrieved May 29, 2013.

- "University lands first of 3 debates", The Clarion-Ledger, Accessed November 20, 2007

- "2008 Presidential Debate - The University of Mississippi - Official Home Page". Archived from the original on December 5, 2008. Retrieved May 29, 2015.

- "Mascot Selection Committee » Rebel Black Bear Selected As New On-Field Mascot for Ole Miss Rebels". Mascot.olemiss.edu. October 14, 2010. Archived from the original on September 4, 2015. Retrieved December 14, 2012.

- "Ole Miss unveils its Landshark mascot, a melding of Rebels history and Hollywood design". The Clarion Ledger.

- "Ole Miss News". News.olemiss.edu. Retrieved December 14, 2012.

- "History | University of Mississippi". www.olemiss.edu. Retrieved November 27, 2018.

- McLaughlin, Eliott C. "Ole Miss removes state flag from campus". CNN. Retrieved May 10, 2019.

- "Students Against Social Injustice protests confederate statues". The Daily Mississippian. November 29, 2018. Retrieved May 10, 2019.

- "Sparks breaks silence, questions about the statue remain - The Daily Mississippian | The Daily Mississippian". thedmonline.com. Retrieved May 10, 2019.

- "Unanimous: ASB Senate votes to move the monument - The Daily Mississippian | The Daily Mississippian". thedmonline.com. Retrieved May 10, 2019.

- "Mississippi Public Universities - BOARD OF TRUSTEES APPROVES UNIVERSITY OF MISSISSIPPI'S REQUEST TO RELOCATE CONFEDERATE MONUMENT". www.mississippi.edu. Archived from the original on July 16, 2020. Retrieved July 20, 2020.

- "The University of Mississippi 2015–2016 Fact Book" (PDF). January 15, 2016.

- "History of Lung Transplantation". Emory University. April 12, 2005. Archived from the original on October 2, 2009. Retrieved September 8, 2009.

- Surgery: First Heart Transplant. Time Magazine. January 31, 1964

- Government runs nation's only legal pot garden. CNN. May 18, 2009

- Internet site shines light on archival blues recordings. Billboard Magazine. June 9, 2001

- "Home". Retrieved May 29, 2015.

- "CME - The Haley Barbour Center for Manufacturing Excellence - About CME". cme.olemiss.edu. Archived from the original on November 20, 2017. Retrieved November 27, 2018.

- "Introduction." Chinese Language Flagship Program, University of Mississippi. Retrieved on May 3, 2012.

- "About the Institute - Trent Lott Leadership Institute". Trent Lott Leadership Institute. Retrieved November 27, 2018.

- "Mississippi Excellence in Teaching Program". Mississippi Excellence in Teaching Program. Retrieved November 27, 2018.

- "School of Education: Special Programs - University of Mississippi". education.olemiss.edu.

- "About the College – Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College". www.honors.olemiss.edu. Retrieved November 27, 2018.

- "SECU". SEC. Retrieved February 13, 2013.

- "SECU: The Academic Initiative of the SEC". SEC Digital Network. Archived from the original on July 21, 2012. Retrieved February 13, 2013.

- "SEC Symposium to address role of Southeast in renewable energy". University of Georgia. Retrieved February 13, 2013.

- "Academic Ranking of World Universities 2020: National/Regional Rank". Shanghai Ranking Consultancy. Retrieved August 15, 2020.

- "America's Top Colleges 2019". Forbes. Retrieved August 15, 2019.

- "U.S. College Rankings 2020". Wall Street Journal/Times Higher Education. Retrieved September 26, 2019.

- "Best Colleges 2020: National University Rankings". U.S. News & World Report. Retrieved September 8, 2019.

- "2019 National University Rankings". Washington Monthly. Retrieved August 20, 2019.

- "Academic Ranking of World Universities 2020". Shanghai Ranking Consultancy. 2020. Retrieved August 15, 2020.

- "QS World University Rankings® 2021". Quacquarelli Symonds Limited. 2020. Retrieved June 10, 2020.

- "Best Global Universities Rankings: 2020". U.S. News & World Report LP. Retrieved October 22, 2019.

- "UM Again Named Among 'Great Colleges to Work For' - Ole Miss News". Ole Miss News. July 16, 2018. Retrieved November 27, 2018.

- "Robust Approach to Campus Safety Places UM in National Rankings - Ole Miss News". Ole Miss News. March 12, 2018. Retrieved November 27, 2018.

- "Bloomberg BusinessWeek Ranks Ole Miss MBA Program in Top 50 - Ole Miss News". Ole Miss News. November 14, 2018. Retrieved November 27, 2018.

- "Ole Miss Online MBA Program Ranks in U.S. News Top 25 - Ole Miss News". Ole Miss News. January 9, 2018. Retrieved November 27, 2018.

- "Accountancy Programs Maintain Top 10 Standing - Ole Miss News". Ole Miss News. October 1, 2018. Retrieved November 27, 2018.

- Winter Institute Receives International Award for Globally Promoting Civil, Human Rights. News.olemiss.edu (September 18, 2012). Retrieved on August 17, 2013.

- "Interfraternity Council - IFC Chapters". catalog.olemiss.edu. Retrieved May 10, 2017.

- "Haunted History". news.olemiss.edu. Retrieved May 10, 2017.

- "Rediscover the Battle of Shiloh". www.thelocalvoice.net. Retrieved May 10, 2017.

- "Frank Gates Dies Here; Rites Today". The Clarion Ledger. Jackson, Mississippi. January 3, 1975. p. 7. Retrieved November 7, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Gates, Frank P., Co. (b.1895 - d.1975)". Mississippi Department of Archives and History. Retrieved November 7, 2017.

- "Landscape Services | University of Mississippi". www.olemiss.edu. Retrieved May 10, 2017.

- "The University of Mississippi – Tupelo". www.outreach.olemiss.edu. Archived from the original on February 7, 2007. Retrieved May 10, 2017.

- "The University of Mississippi – DeSoto". www.outreach.olemiss.edu. Archived from the original on July 9, 2010. Retrieved May 10, 2017.

- "The University of Mississippi – Grenada". www.outreach.olemiss.edu. Archived from the original on August 17, 2011. Retrieved May 10, 2017.

- "Ole Miss Sports website".

- "Ole Miss Athletics website".

- "NCAA Football Championship History".

- Garner, Dwight (October 14, 2011). "Faulkner and Football in Oxford, Miss". The New York Times.

- "maps location".

- "Bjork Press Conference" March 22, 2012". Archived from the original on October 16, 2012.

- "Office of Leadership & Advocacy". dos.orgsync.com. Retrieved November 27, 2018.

- The Ole Miss Archived August 3, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- "Buildings - Student Housing". Student Housing. Retrieved November 27, 2018.

- Student Housing – The University of Mississippi Archived October 1, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- Student Housing – The University of Mississippi Archived December 8, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- Student Housing and Residence Life – The University of Mississippi Archived October 1, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- "Village." University of Mississippi. Retrieved on February 2, 2012.

- "Campus Map." University of Mississippi. Retrieved on February 2, 2012.

- "Our Schools Archived 2012-02-21 at the Wayback Machine." Oxford School District. Retrieved on February 2, 2012.

- "TWO SECRET SOCIETIES UNITED. - DELTA TAU DELTA AND THE RAINBOW SOCIETY JOIN HANDS. - View Article - NYTimes.com" (PDF). March 28, 1885. Retrieved April 30, 2016.

- "Mississippi History Now - Lee Maurice Russell: Fortieth Governor of Mississippi: 1920-1924". Retrieved May 29, 2015.

- "UM chapter of Kappa Alpha Theta to close this semester - The Daily Mississippian - The Daily Mississippian". thedmonline.com.

- "Associated Student Body". Associated Student Body. Retrieved October 3, 2019.

- "Code and Constitution". Associated Student Body.

- https://irep.olemiss.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/98/2018/02/Mini-Fact-Book-in-Excel_2017-2018.pdf

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to University of Mississippi. |

| Wikisource has the text of a 1905 New International Encyclopedia article about University of Mississippi. |

- Official website

- Ole Miss Athletics website