Subcomandante Marcos

Rafael Sebastián Guillén Vicente (born June 19, 1957)[1] is a Mexican insurgent, former military leader, and spokesman for the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN) in the ongoing Chiapas conflict.[2] Widely known by his previous nom de guerre as Subcomandante Marcos, he has recently used several other pseudonyms; he referred to himself as Delegate Zero during the 2006 Mexican presidential campaign. In May 2014, he adopted the name of his dead comrade "Teacher Galeano",[3] naming himself Subcomandante Galeano instead.

Subcomandante Marcos | |

|---|---|

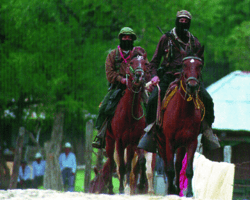

Subcomandante Marcos, smoking a pipe atop a horse in Chiapas, Mexico in 1996. | |

| Born | June 19, 1957 Tampico, Tamaulipas, Mexico |

| Nationality | Mexican |

| Other names |

|

| Education | Instituto Cultural Tampico |

| Alma mater | National Autonomous University of Mexico (MPhil) |

| Occupation | |

| Movement | Neozapatismo |

| Military career | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | |

| Years of service | 1994–2014 |

| Rank | Subcommander |

| Battles/wars | Chiapas conflict • Zapatista uprising |

| Website | Official website |

Born in Tampico, Tamaulipas, Marcos earned a degree in sociology and a master's degree in philosophy from the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM),[4] and taught at the Autonomous Metropolitan University (UAM) for several years during the early 1980s.[1] During this time he became increasingly involved with a guerrilla group known as the National Liberation Forces (FLN), before leaving the university and moving to Chiapas in 1984.[1]

The Ejército Zapatista de Liberación Nacional (EZLN) (Zapatista Army of National Liberation) was founded in the Lacandon Jungle in 1983, initially functioning as a self-defense unit dedicated to protecting Chiapas' Mayan people from evictions and encroachment on their land. While not Mayan himself, Marcos emerged as the group's leader, and when the EZLN – often referred to as Zapatistas – began their rebellion on January 1, 1994, Marcos served as their spokesman.[2]

Known for his trademark ski mask and pipe, and for his charismatic personality, Marcos led the EZLN during the 1994 revolt and the subsequent peace negotiations, during a counter-offensive by the Mexican Army in 1995, and throughout the decades that followed. In 2001, he led a group of Zapatista leaders into Mexico City to meet with President Vicente Fox, attracting widespread public and media attention. In 2006, Marcos made another public tour of Mexico, which was known as The Other Campaign. In May 2014, Marcos stated that the persona of Subcomandante Marcos had been "a hologram" and no longer existed. Many media outlets interpreted the message as Marcos retiring as the Zapatistas' leader and spokesman.[5]

Marcos is also a prolific writer, and hundreds of essays and multiple books are attributed to him. Most of his writings focus on his anti-capitalist ideology and the advocacy for indigenous people's rights, but he has also written poetry and novels.[6]

Early life

Guillén was born on 19 June 1957, in Tampico, Tamaulipas, to Alfonso Guillén and Maria del Socorro Vincente.[7] He was the fourth of eight children.[1] A former elementary school teacher,[4] Alfonso owned a chain of furniture stores, and the family is usually described as middle-class.[8][7] In a 2001 interview with Gabriel García Márquez and Roberto Pombo, Guillén described his upbringing as middle-class, "without financial difficulties", and said his parents fostered a love for language and reading in their children.[9]

Guillén attended high school at the Instituto Cultural Tampico, a Jesuit school in Tampico.[10][11] Later he moved to Mexico City and graduated from the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM), majoring in philosophy. There he became immersed in the school's pervasive Marxist rhetoric of the 1970s and 1980s and won an award for the best dissertation (drawing on the then-recent work of Althusser and Foucault) of his class. He began working as a professor at the Autonomous Metropolitan University (UAM) while finishing his dissertation at UNAM, but left after a couple of years. It is thought that it was at UAM where he got in touch with the Forces of National Liberation, the mother organization of what would later become the EZLN.

Marcos was radicalized by the Tlatelolco massacre (2 October 1968) of students and civilians by the Mexican federal government; consequently, he became a militant in the Maoist National Liberation Forces. In 1983, he went to the mountains of Chiapas to convince the poor, indigenous Mayan population to organize and launch a proletarian revolution against the Mexican bourgeoisie and the federal government.[12] After hearing his proposition, the Chiapanecs "just stared at him," and replied that they were not urban workers, and that from their perspective the land was not property, but the heart of the community.[12] In the documentary A Place Called Chiapas (1998), about his early days there, Subcommander Marcos said:

Imagine a person who comes from an urban culture. One of the world's biggest cities, with a university education, accustomed to city life. It's like landing on another planet. The language, the surroundings are new. You're seen as an alien from outer space. Everything tells you: "Leave. This is a mistake. You don't belong in this place"; and it's said in a foreign tongue. But they let you know, the people, the way they act; the weather, the way it rains; the sunshine; the earth, the way it turns to mud; the diseases; the insects; homesickness. You're being told. "You don't belong here." If that's not a nightmare, what is?

There are several rumors that Marcos left Mexico in the mid-1980s to go to Nicaragua to serve with the Sandinistas under the nom de guerre El Mejicano. After leaving Nicaragua in the late 1980s, he returned to Mexico and helped form the EZLN with support from the Sandinistas and the Salvadoran leftist guerrilla group FMLN.[13][14][15] Some believe that this contradicts the view that the first Zapatista organizers were in the jungle by 1983, but it is known that the real founders of the EZLN foco were the brothers Fernando (a.k.a. German) and Cesar (a.k.a. Pedro) Yañez-Muñoz, who were previously part of the FLN guerrillas. Marcos took over the remnants of the FLN after Pedro was killed and German captured.[16][17][18]

Guillén's sister Mercedes Guillén Vicente is the Attorney General of the State of Tamaulipas, and an influential member of the Institutional Revolutionary Party.[19][20][21][4]

Zapatista Crisis

Military site

Once Subcomandante Marcos was identified as Rafael Sebastián Guillén Vicente, on 9 February 1995, President Ernesto Zedillo decided to launch a military offensive to capture or annihilate Marcos and the Zapatistas.[22] Arrest warrants were issued for Marcos,[23] Javier Elorriaga Berdegue, Silvia Fernández Hernández, Jorge Santiago, Fernando Yanez, German Vicente, Jorge Santiago and other Zapatistas. The Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN) was besieged by the Mexican Army in the Lacandon Jungle.

Marcos's resolve was put to the test in his camp in the Lacandon Jungle when the Zapatistas were under military siege by the Mexican Army. His response was immediate, sending Secretary of the Interior Lic. Esteban Moctezuma the following message: "See you in hell." There were conflicting signals in favor of a fast military solution. The facts seemed to confirm Manuel Camacho Solis's 16 June 1994 assertion that the reason he resigned as Chiapas Peace Commissioner was sabotage by Zedillo.

Under the political pressure of a highly radicalized situation, Moctezuma believed a peaceful solution was possible. He championed a negotiated solution to the 1995 Zapatista Crisis, betting on a creative strategy to reestablish Mexican–EZLN dialogue. Taking a strong position against the 9 February actions, Moctezuma submitted his resignation to Zedillo, who refused it and asked Moctezuma to try to restore conditions that would allow for dialogue and negotiation. For these reasons the Mexican army moderated their actions, providing an opportunity that Marcos capitalized upon to escape the military site in the Lacandon Jungle.

Faced with this situation, Max Appedole, Guillén's childhood friend and colleague at the Jesuits College Instituto Cultural Tampico, asked for help from Edén Pastora, the legendary Nicaraguan "Commander Zero"; they prepared a report for Under-Secretary of the Interior Luis Maldonado Venegas, Moctezuma, and President Zedillo about Marcos's natural pacifist vocation and the consequences of a military outcome.[24] The document concluded that the complaints of marginalized groups and the radical left in México had been vented through the Zapatistas movement, while Marcos maintained an open negotiating track. If Marcos was to be eliminated, his work at social containment would cease and more-radical groups could take his place. These groups would respond to violence with violence, threatening terrorist bombings, kidnappings and belligerent activities. The country would be in a very dangerous spiral, with discontent in areas other than Chiapas.[25]

Decree for reconciliation and peace

On 10 March 1995 Zedillo and Moctezuma signed the Presidential Decree for the Dialog, the Reconciliation and a Peace with Dignity in Chiapas Law. It was discussed and approved by the Mexican Congress.[26]

Restoration of the peace talks

On the night of 3 April 1995 at 8:55 pm the first meeting between representatives of the EZLN and Zedillo were held. Moctezuma sent Maldonado to deliver a letter to Zapatista representatives in radio communication with Marcos expressing Moctezuma's commitment to a political path to resolve the conflict.[27]

In contrast to many other talks—with broad media exposure, strong security measures, and great ceremony—Maldonado decided on secret talks, alone, without any disruptive security measures. He went to the Lacandon Jungle to meet with Marcos. Secret negotiations took place in Prado Pacayal, Chiapas, witnessed by Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas Batel. Marcos and Maldonado established parameters and a location for the peace dialogue between the parties. After several days of unfruitful negotiations, without reaching any specific agreements, Maldonado proposed an indefinite suspension of hostilities. On his way out, he said, "If you do not accept this, it will be regretted not having made the installation of the formal dialogue in the time established by the Peace Talks Law." Marcos took this as a direct threat, and did not reply.

Marcos gave a statement to the Witness of Honor, Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas Batel:

You have been witness to the fact that we have not threatened or assaulted these people, they have been respected in their person, property, their liberty and life. You have witnessed that the Zapatista Army of National Liberation has a word and has honor; you have also been witness to our willingness to engage in dialog. Thank you for taking the trouble to come all the way down here and have contributed with your effort to a peaceful settlement of the conflict, we hope that you will continue contributing in this effort to avoid war and you and your family, continue accepting to be witnesses of honor in this dialog and negotiation process.

Marcos asked Batel to accompany Moctezuma and Maldonado to Ocosingo to verify their departure in good health. The meeting ended 7 April 1995 at 4:00 am.[28]

Peace

Without much hope of dialogue, Maldonado began his return to Mexico City under hostile conditions. When passing by the Ejido, San Miguel, a Zapatista patrol beckoned them to stop. Maldonado, surprised and not knowing what was happening, was handed a radio. Using it, he and Marcos resumed their dialogue, and made agreements in accordance with the law to start the formal peace talks. Marcos convinced the Zapatista movement to put down their arms and begin talks to reach a peace agreement.[29][30]

Protocol

By 9 April 1995, the basis for the Dialog Protocol and the harmony, peace with justice and dignity agreement negotiation between the Mexican government and the Zapatistas was signed. On 17 April the Mexican government appointed Marco Antonio Bernal as Peace Commissioner in Chiapas.[31] The peace talks began in San Andrés Larráinzar on 22 April, but the Zapatistas rejected the Mexican government's proposal. Peace talks resumed on 7 June 1995. The parties agreed with Alianza Cívica Nacional and the Convención Nacional Democrática to organize a national consultation for peace and democracy. The basis for the dialogue protocol was renegotiated, in La Realidad, Chiapas. On 12 October 1995 peace talks resumed in San Andres Larráinzar.[32]

The Other Agenda

The difficulties encountered during the peace talks between the government and the Zapatistas were due mostly to the initiatives promoted by the Attorney General of Mexico (PGR). On 23 October 1995, in order to derail the peace talks, the PGR arrested and sent Fernando Yañez Muñoz to prison. This violated the governing peace talks law, which guaranteed free passage to all Zapatistas during the negotiations and suspended outstanding arrest warrants against them. On 26 October, the Zapatista National Liberation Army denied any association with Muñoz and announced a Red Alert, while Marcos returned to the mountains. That same day, the PGR dropped all charges against the alleged Comandante German. The COCOPA (Comisión de Concordia y Pacificación, Commission of Concord and Pacification) agreed with the determination. On 27 October, Muñoz was freed from the Reclusorio Preventivo Oriente.[33] He said, "I was arrested for political reasons and I guess I am set free for political reasons. My arrest was with the objective purpose of sabotaging the peace talks."[34] On 29 October 1995 the Zapatistas lifted the Red Alert and negotiations resumed.

Executive decision

Finding a non-military, peaceful solution to the 1995 Zapatista Crisis was politically and honorably correct, saving many lives in México. After a rocky start because of conflicting intelligence, Moctezuma was able to give Zedillo proper information. Zedillo avoided bloodshed by changing course, reversing the 9 February 1995 decision that had brought him heavy political criticism.

Release of the prisoners

On appeal, the Court dismissed the previous sentences given on 2 May 1996 for the crime of terrorism to the alleged Zapatistas Javier Elorriaga and Sebastian Etzin Gomez, of 13 and 6 years of imprisonment, respectively. They were released on 6 June 1996.[35] The EZLN then suspended their troops' alert status.

Political and philosophical writings

Marcos has written more than 200 essays and stories, and has published 21 books documenting his political and philosophical views. The essays and stories are compiled in the books. Marcos tends to prefer indirect expression, and his writings are often fables, although some are more earthy and direct. In a January 2003 letter to Euskadi Ta Askatasuna (the Basque ETA separatist group), titled "I Shit on All the Revolutionary Vanguards of This Planet", Marcos says: "We teach [children of the EZLN] that there are as many words as colors and that there are so many thoughts because within them is the world where words are born...And we teach them to speak with the truth, that is to say, to speak with their hearts."[36]

La Historia de los Colores (The Story of Colors) is a story written for children and is one of Marcos' most-read books. Based on a Mayan creation myth, it teaches tolerance and respect for diversity.[37] The book's English translation was to be published with support from the U.S. National Endowment for the Arts, but in 1999 the grant was abruptly canceled after questions from a reporter to the Endowment's chairman William J. Ivey.[38][39] The Lannan Foundation provided support after the NEA withdrew.[40]

Marcos' political philosophy is often characterized as Marxist and his writings, which concentrates on strong criticism of people by both business and the State, underlines some of the commonalities the Zapatista ideology shares with Libertarian socialism and Anarchism.

The elliptical, ironic, and romantic style of Marcos' writings may be a way of keeping a distance from the painful circumstances that he reports on and protests. His literary output has a purpose, as suggested in a 2002 book titled, Our Word is Our Weapon, a compilation of his articles, poems, speeches, and letters.[41][42] In 2005, he wrote the novel The Uncomfortable Dead with the whodunit writer Paco Ignacio Taibo II.

Fourth World War

Subcomandante Marcos has also written an essay in which he claims that neoliberalism and globalization constitute the "Fourth World War".[43] He termed the Cold War the "Third World War".[43] In this piece, Marcos compares and contrasts the Third World War (the Cold War) with the Fourth World War, which he says is the new type of war that we find ourselves in now: "If the Third World War saw the confrontation of capitalism and socialism on various terrains and with varying degrees of intensity, the fourth will be played out between large financial centers, on a global scale, and at a tremendous and constant intensity."[43] He goes on to claim that economic globalization has created devastation through financial policies:[43]

Toward the end of the Cold War, capitalism created a military horror: the neutron bomb, a weapon that destroys life while leaving buildings intact. During the Fourth World War, however, a new wonder has been discovered: the financial bomb. Unlike those dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, this new bomb not only destroys the polis (here, the nation), imposing death, terror, and misery on those who live there, but also transforms its target into just another piece in the puzzle of economic globalization.

Marcos explains the effect of the financial bombs as, "destroying the material bases of their [nation-state's] sovereignty and, in producing their qualitative depopulation, excluding all those deemed unsuitable to the new economy (for example, indigenous peoples)".[43] Marcos also believes that neoliberalism and globalization result in a loss of unique culture for societies as a result of the homogenizing effect of neo-liberal globalization:[43]

All cultures forged by nations – the noble indigenous past of America, the brilliant civilization of Europe, the wise history of Asian nations, and the ancestral wealth of Africa and Oceania – are corroded by the American way of life. In this way, neoliberalism imposes the destruction of nations and groups of nations in order to reconstruct them according to a single model. This is a planetary war, of the worst and cruelest kind, waged against humanity.

It is in this context which Subcomandante Marcos believes that the EZLN and other indigenous movements across the world are fighting back. He sees the EZLN as one of many "pockets of resistance".[43]

It is not only in the mountains of southeastern Mexico that neoliberalism is being resisted. In other regions of Mexico, in Latin America, in the United States and in Canada, in the Europe of the Maastricht Treaty, in Africa, in Asia, and in Oceania, pockets of resistance are multiplying. Each has its own history, its specificities, its similarities, its demands, its struggles, its successes. If humanity wants to survive and improve, its only hope resides in these pockets made up of the excluded, the left-for-dead, the 'disposable'.

Marcos' views on other Latin American leaders, particularly ones on the left, are complex. He has expressed deep admiration for former Cuban president Fidel Castro and Argentine revolutionary Che Guevara, and given his approval to Bolivian president Evo Morales, but has expressed mixed feelings for Hugo Chavez of Venezuela, whom he views as too militant, but still responsible for vast revolutionary changes in Venezuela. On the other hand, he has labeled Brazil's former president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva and Nicaragua's current president Daniel Ortega, whom he once served under while a member of the Sandinistas, as traitors who have betrayed their original ideals.[44][45]

Popularity

Marcos is often credited with putting the impoverished state of Mexico's indigenous population in the spotlight, both locally and internationally.[6] On his 3,000-kilometre (1,900 mi) trek to the capital during the Other Campaign in 2006, Marcos was welcomed by "huge adoring crowds, chanting and whistling".[6] There were "Marcos handcrafted dolls, and his ski mask-clad face adorns T-shirts, posters and badges."[6]

Relationship with Inter Milan

Apart from cheering for local Liga MX side Chiapas F.C., which relocated to Querétaro in 2013, Subcomandante Marcos and the EZLN also support the Italian Serie A club Inter Milan.[46] The contact between EZLN and Inter, one of Italy's biggest and most famous clubs, began in 2004 when an EZLN commander contacted a delegate from Inter Campus, the club's charity organization which has funded sports, water, and health projects in Chiapas.

In 2005, Inter's president Massimo Moratti received an invitation from Subcomandante Marcos to have Inter play a football game against a team of Zapatistas with Diego Maradona as referee. Subcomandante Marcos asked Inter to bring the match ball because the Zapatistas' ones were punctured.[47] Although the proposed spectacle never came to fruition, there has been continuing contact between Inter and the Zapatistas. Former captain Javier Zanetti has expressed sympathy for the Zapatista cause.[48]

See also

Notes and references

- Nick Henck (18 June 2007). Subcommander Marcos: The Man and the Mask. Duke University Press. pp. 11–. ISBN 978-0-8223-8972-9. Archived from the original on 21 April 2017.

- Pasztor, S. B. (2004). Marcos, Subcomandante. In D. Coerver, S. Pasztor & R. Buffington, Mexico: An encyclopedia of contemporary culture and history. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO

- C.V, DEMOS, Desarrollo de Medios, S. A. de (25 May 2014). "La Jornada: El asesinato de José Luis Solís López, Galeano". Jornada.com.mx. Retrieved 16 February 2019.

- Roderic Ai Camp (1 October 2011). Mexican Political Biographies, 1935-2009: Fourth Edition. University of Texas Press. pp. 445–. ISBN 978-0-292-72634-5.

- Althaus, Dudley (27 May 2014). "Mexican Rebel Leader Subcomandante Marcos Retires, Changes Name". Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 3 October 2016.

- BBC Profile: The Zapatistas' mysterious leader Archived 18 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine by Nathalie Malinarich, 11 March 2001

- Lee Stacy (1 October 2002). Mexico and the United States. Marshall Cavendish. pp. 386–. ISBN 978-0-7614-7402-9.

- "Subcomandante Marcos: The Punch Card and the Hourglass. New Left Review 9, May-June 2001". Archived from the original on 18 May 2016.

- The Punch Card and the Hourglass Archived 27 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine by García Márquez and Roberto Pombo, New Left Review, May – June 2001, Issue 9

- Gabriel García Márquez y Roberto Pombo (25 March 2001). "Habla Marcos". Cambio (Ciudad de México). Archived from the original on 22 May 2006. A discussion of Marcos's background and views. Marcos says his parents were both schoolteachers and mentions early influences of Cervantes and García Lorca.

- Gabriel García Márquez and Subcomandante Marcos (2 July 2001). "A Zapatista Reading List". The Nation. An abbreviated version of the Cambio article, in English.

- Farewell to the End of History: Organization and Vision in Anti-Corporate Movements Archived 28 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine by Naomi Klein, The Socialist Register, 2002, London: Merlin Press, 1–14

- "WAIS - World Affairs Report - Bishop Samuel Ruiz". Archived from the original on 17 October 2013.

- "High hopes, baffling uncertainty: Mexico nears the millennium : Mexico History". Mexconnect.com.

- "Mexico Unmasks Guerrilla Commander Subcomandante Marcos Really Is Well-Educated Son Of Furniture-Store Owner". Archived from the original on 24 May 2013.

- Henck, Nick (18 June 2007). Subcommander Marcos: The Man and the Mask. Duke University Press. ISBN 9780822389729. Retrieved 16 February 2019 – via Google Books.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 28 January 2016. Retrieved 22 January 2016.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Jornada, La. "Rinde Marcos homenaje público a los fundadores del Ejército Zapatista - La Jornada". Archived from the original on 27 January 2016.

- Alex Khasnabish (2003). "Subcomandante Insurgente Marcos". MCRI Globalization and Autonomy. Archived from the original on 30 May 2012.

- Hector Carreon (8 March 2001). "Aztlan Joins Zapatistas on March into Tenochtitlan". La Voz de Aztlan. Archived from the original on 6 May 2006.

- El EZLN (2001). "La Revolución Chiapanequa". Zapata-Chiapas. Archived from the original on 16 June 2002.

- "Memoria Política de México". Archived from the original on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 14 December 2015.

- tvinsomne (23 September 2009). "PGR ordena la captura y devela la identidad del Subcomandante Marcos (9 de febrero 1995)". YouTube. Retrieved 16 February 2019.

- "Tampico la conexion zapatista". Archived from the original on 3 November 2013.

- "Marcos, en la mira de Zedillo - Proceso". 5 August 2002. Archived from the original on 17 October 2013.

- "Client Validation". Archived from the original on 2 November 2013.

- Salas, Javier Rosiles. "MORENO VALLE-TV AZTECA: EL TÁNDEM POBLANO". Archived from the original on 24 July 2016.

- Carolia, Ana. "Sobre mis pasos de Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas Solórzano". Archived from the original on 2 November 2013. Retrieved 14 December 2015.

- México, El Universal, Compañia Periodística Nacional. "El Universal - Opinion - Renuncia en Gobernación". Archived from the original on 2 November 2013.

- "LUIS MALDONADO VENEGAS Y SU PARTICIPACIÓN EN EL PROCESO DE PACIFICACIÓN EN CHIAPAS". 31 January 2011. Archived from the original on 6 November 2013.

- "Los caminos de Chiapas: agosto 2006". Archived from the original on 6 November 2013.

- Admservice. "Cronologia del Conflicto EZLN". Archived from the original on 28 November 2012.

- "alzamiento y lucha Zapatista Pag. 7". Ensayoes.com.

- "LIBERADO SUPUESTO LÍDER GUERRILLERO EN MÉXICO - Archivo Digital de Noticias de Colombia y el Mundo desde 1.990". Archived from the original on 4 November 2013.

- «La Jornada: 16 meses despues» Archived 5 November 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- Zapatista National Liberation Army (9 January 2003). "To Euskadi Ta Askatasuna". Flag. Archived from the original on 13 June 2006.

- Patrick Markee (16 May 1999). "Hue and Cry". New York Times. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016.

- Bobby Byrd (2003). "The Story Behind The Story of Colors". Cinco Puntos Press. Archived from the original on 6 September 2015.

- Julia Preston (10 March 1999). "U.S. Cancels Grant for Children's Book Written by Mexican Guerrilla". New York Times. This article was retitled "N.E.A. Couldn't Tell a Mexican Rebel's Book by Its Cover" in late editions.

- Irvin Molotsky (11 March 1999). "Foundation Will Bankroll Rebel Chief's Book N.E.A. Dropped". New York Times.

- Alma Guillermoprieto (2 March 1995). "The Shadow War". New York Review of Books. This book review recounts problems faced by residents of Chiapas.

- Paul Berman (18 October 2001). "Landscape Architect". New York Review of Books.

- The Fourth World War Has Begun by Subcomandante Marcos, trans. Nathalie de Broglio, Neplantla: Views from South, Duke University Press: 2001, Vol. 2 Issue 3: 559–572

- Agencias. ""Subcomandante Marcos" dice que Chávez tiene "improntas de caudillo"". Archived from the original on 13 October 2013.

- Tuckman, Jo (12 May 2007). "Man in the mask returns to change world with new coalition and his own sexy novel". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 21 September 2016.

- "Spegnere il fuoco con la benzina". 12 January 2013. Archived from the original on 3 October 2016.

- "Repubblica.it » sport/calcio » Il subcomandante Marcos sfida l'Inter "Davanti alla porta non avrei pietà"". Archived from the original on 8 September 2012.

- "Zapatista rebels woo Inter Milan". BBC News. 11 May 2005. Archived from the original on 14 December 2013.

Further reading

Books (in English) specifically on Marcos

- Nick Henck, Subcommander Marcos: the Man and the Mask (Durham, NC, 2007)

- Daniela Di Piramo, Political Leadership in Zapatista Mexico: Marcos, Celebrity, and Charismatic Authority (Boulder, CO, 2010)

- Nick Henck, Insurgent Marcos: The Political-Philosophical Formation of the Zapatista Subcommander (Raleigh, NC, 2016)

- Fernando Meisenhalter, A Biography of the Subcomandante Marcos: Rebel Leader of the Zapatistas in Mexico (Kindle, 2017)

- Nick Henck, Subcomandante Marcos: Global Rebel Icon (Montreal, 2019)

Edited Collections (in English) of Marcos’ Writings

- Autonomedia, ¡Zapatistas! Documents of the New Mexican Revolution (New York, 1994)

- Clarke, Ben and Ross, Clifton, Voices of Fire: Communiqués and Interviews from the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (San Francisco, 2000)

- Ross, John and Bardacke, Frank (eds.), Shadows of a Tender Fury: The Communiqués of Subcomandante Marcos and the EZLN (New York, 1995)

- Ruggiero, Greg and Stewart Shahulka (eds.), Zapatista Encuentro: Documents from the 1996 Encounter for Humanity and Against Neoliberalism (New York, 1998)

- Subcomandante Marcos, The Story of Colors / La Historia de los Colores (El Paso, 1999)

- Subcomandante Marcos, Our Word is Our Weapon. Juana Ponce de León (ed.), (New York, 2001)

- Subcomandante Marcos, Questions and Swords (El Paso, 2001)

- Subcomandante Marcos, Zapatista Stories. Transl. by Dinah Livingstone (London, 2001)

- Subcomandante Marcos, Ya Basta! Ten Years of the Zapatista Uprising. Žiga Vodovnik (ed.), (Oakland, CA, 2004)

- Subcomandante Marcos, Conversations with Durito: Stories of the Zapatistas and Neoliberalism (New York, 2005)

- Subcomandante Marcos, Chiapas: Resistance and Rebellion (Coimbatore, India, 2005)

- Subcomandante Marcos, The Other Campaign (San Francisco, 2006)

- Subcomandante Marcos, The Speed of Dreams (San Francisco, 2007)

- Subcomandante Marcos, Critical Thought in the Face of the Capitalist Hydra (Durham, NC, 2016)

- Subcomandante Marcos, Professionals of Hope: The Selected Writings of Subcomandante Marcos (Brooklyn, NY, 2017)

- Subcomandante Marcos, The Zapatistas’ Dignified Rage: Final Public Speeches of Subcommander Marcos. Nick Henck (ed.) and Henry Gales (trans.), (Chico, CA, 2018)

Miscellaneous Books

- Anurudda Pradeep (2006). Zapatista.

- Nick Henck (2007). Subcommander Marcos: the man and the mask. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Mihalis Mentinis (2006). ZAPATISTAS: The Chiapas Revolt and What It Means for Radical Politics. London: Pluto Press.

- John Ross (1995). Rebellion from the Roots: Indian Uprising in Chiapas. Monroe, ME: Common Courage Press.

- George Allen Collier and Elizabeth Lowery Quaratiello (1995). Basta! Land and the Zapatista Rebellion in Chiapas. Oakland, CA: Food First Books.

- Bertrand de la Grange and Maité Rico (1997). Marcos: La Genial Impostura. Madrid: Alfaguara, Santillana Ediciones Generales.

- Yvon Le Bot (1997). Le Rêve Zapatiste. Paris, Éditions du Seuil.

- Maria del Carmen Legorreta Díaz (1998). Religión, Política y Guerrilla en Las Cañadas de la Selva Lacandona. Mexico City: Editorial Cal y Arena.

- John Womack Jr. (1999). Rebellion in Chiapas: An Historical Reader. New York: The New Press.

- Manuel Vázquez Montalbán (1999). Marcos: el Señor de los Espejos. Madrid: Aguilar.

- Ignacio Ramonet (2001). Marcos. La dignité rebelle. Paris: Galilée. Subtitled Conversations avec le Sous-commandant Marcos.

- Manuel Vázquez Montalbán (2001). Marcos Herr der Spiegel. Berlin: Verlag Klaus Wagenbach. German translation of Marcos: el Señor de los Espejos.

- Alma Guillermoprieto (2001). Looking for History: Dispatches from Latin America. New York: Knopf Publishing Group.

- Manuel Vázquez Montalbán (2003). Marcos, le Maître des Miroirs. Montréal: Éditions Mille et Une Nuits. French translation of Marcos: el Señor de los Espejos.

- Gloria Muñoz Ramírez (2008). The Fire and the Word: A History of the Zapatista Movement. City Lights Publishers. ISBN 978-0-87286-488-7.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Subcomandante Marcos |

- EZLN and Subcomandante Marcos official web page

- Profile: The Zapatistas' mysterious leader, BBC News

- Subcomandante Marcos tribute web page

- Works by or about Subcomandante Marcos in libraries (WorldCat catalog)

- A Place Called Chiapas - a 1998 Documentary by Nettie Wild about the Zapatista movement.

- Narco News: Subcomandante Marcos Pays Homage to Che Guevara and Praises Cuba 11 October 2006.

- Writings of Subcomandante Marcos

- Revolution Rocks: Thoughts of Mexico's First Postmodern Guerrilla Commander by The New York Times

- The Death Train of the WTO: The Slaves of Money and Our Rebellion by Subcomandante Marcos

- From Che to Marcos by Jeffrey W. Rubin, Dissent Magazine, Summer 2002