Industrial unionism

Industrial unionism is a labour union organizing method through which all workers in the same industry are organized into the same union—regardless of skill or trade—thus giving workers in one industry, or in all industries, more leverage in bargaining and in strike situations. Advocates of industrial unionism value its contributions to building unity and solidarity, many suggesting the slogans, "an injury to one is an injury to all" and "the longer the picket line, the shorter the strike."

Industrial unionism contrasts with craft unionism, which organizes workers along lines of their specific trades, i.e., workers using the same kind of tools, or doing the same kind of work with approximately the same level of skill,[1] even if this leads to multiple union locals (with different contracts, and different expiration dates) in the same workplace.

Perceived disadvantages of craft unionism

In 1922, Marion Dutton Savage cataloged the disadvantages of craft unionism, as observed by industrial union advocates. These included "distressingly frequent disputes between different craft unions" over jurisdiction; modern industry results in a constant process of phasing out old skills; one trade doing the struck work of another entity is a frequent dilemma; expiration of contracts can be staggered, hindering coordination of strikes.[2] Industrial unionists observe that craft union members are more often required by their contracts to cross the picket lines established by workers in other unions. Likewise, in a strike of (for example) coal miners, unionized railroad workers may be required by their contracts to haul "scab" coal.

Employers find it easier to enforce one bad contract, then use that as a precedent. Employers could also show favoritism to a strategic group of workers. Employers also find it easier to outsource the struck work of a craft union.[2]

A craft union with critical skills may be able to shut down an entire industry. The disadvantage is the harsh feelings of those who may be forced out of work by such an action, yet receive none of the bargained-for benefits.[3]

Arguments for industrial unionism

Savage observed that industrial unionists criticized craft unionism not only for the ineffectiveness in dealing with a single employer, but also against larger corporate conglomerates. A union that challenges such a combination is most effective if its own structure reflects that of the company. Industrial unions likewise do not normally assess prohibitive dues rates common with craft unions, which serve to keep out many workers. Thus, the entire group of workers finds solidarity more elusive.[4]

Spirit and philosophy of industrial unionism

The concept of industrial unionism is important, not only to organized workers but also to the general public, because the philosophy and spirit of this organizing principle go well beyond the mere structure of a union organization.[5] According to Marian Dutton Savage, who wrote about industrial unionism in America in 1922,

It is this difference in spirit and general outlook which is the significant thing about industrial unionism. Including as it does all types of workers, from the common laborer to the most highly skilled craftsman, the industrial union is based on the conception of the solidarity of labor, or at least of that portion of it which is in one particular industry. Instead of emphasizing the divisions among the workers and fostering a narrow interest in the affairs of the craft regardless of those of the industry as a whole, it lays stress on the mutual dependence of the skilled and the unskilled and the necessity of subordinating the interests of a small group to those of the whole body of workers. Not only is loyalty to fellow-workers in the same industry emphasized, but also loyalty to the whole working class in its struggle against the capitalist system.[5]

Savage noted that some industrial unions of the period had "little of this class consciousness, [however] the majority of them are distinctly hoping for the abolition of the capitalist system and the ultimate control of industry by the workers themselves."[5]

The conception of how this was to be brought about, and indeed even the extent to which such ideas were present in an industrial union, was quite variable from one union to another,[6] as well as from one country to another, and from one time to another.

In the United States, the conception of industrial unionism in the 1920s certainly differed from that of the 1930s, for example. The Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) primarily practiced a form of industrial unionism prior to its 1955 merger with the American Federation of Labor (AFL), which was mostly craft unions. Unions in the resulting federation, the AFL-CIO, sometimes have a mixture of tendencies.

The most basic philosophy of the union movement observes that an individual cannot stand alone against the power of the company, for the employment contract confers advantage to the employer. Having come to that understanding, the next question becomes: who is to be included in the union?

- The craft unionist advocates sorting workers into exclusive groups of skilled workers, or workers sharing a particular trade. The organization operates, and the rules are formulated primarily to benefit members of that particular group.

- Savage identified a skilled group that may not be craft based, but is nonetheless an elite group among industrial unionists. They are in essence craft groups which have been combined to solve "jurisdictional difficulties". Savage called this group an industrial union tendency rather than an example, made up of the "upper stratum of skilled trades," and describes them as retaining some autonomy within their particular trades.[7]

- The industrial unionist sees advantage in organizing by industry. The local organization is broader and deeper, with less opportunity for employers to turn one group of workers against another. These are the "middle stratum" of workers.[7]

- Industrial unionists motivated by a more global impulse act upon a universal premise, that all workers must support each other no matter their particular industry or locale. These might be unskilled or migratory workers who conceive of their union philosophy as one big union. In 1922 these workers were described as "believing in assault rather than in agreements with employers, and having little faith in political action. [The one big union's] power is spectacular rather than continuous, as its members have little experience in organization."[7]

The differences illustrated by these diverse approaches to organizing touch upon a number of philosophical issues:

- Should all working people be free—and perhaps even obliged—to support each other's struggles?

- What is the purpose of the union itself—is it to get a better deal for a small group of workers today, or to fight for a better environment for all working people in the future? (Or both... ? )

But some philosophical issues transcend the current social order:

- Should the union acknowledge that capital has priority—that is, that employers should be allowed to make all essential decisions about running the business, limiting the union to bargaining over wages, hours, and conditions? Or should the union fight for the principle that working people create wealth, and are therefore entitled to access to that wealth?

- What is the impact of legislation designed specifically to curtail union tactics? Considering that unions have sometimes won rights by defying unjust laws, what should be the attitude of unionists toward that legislation? And finally, how does the interaction between aggressive unionization, and government response, play out?

In short, these are questions of whether workers should organize as a craft, by their industry, or as a class.

The implications of these last conjectures are considerable. When a group of workers becomes conscious of some connection to all other workers, such realization may animate a desire not just for better wages, hours, and working conditions, but rather, to change the system that limits or withholds such benefits. Paul Frederick Brissenden acknowledged as much in his 1919 publication The I.W.W. A Study of American Syndicalism. Brissenden described revolutionary industrial unionism as industrial unionism "animated and guided by the revolutionary (socialist or anarchist) spirit..."[8] Brissenden wrote that both industrial unionism and revolutionary industrial unionism "hark back in their essential principles to [a] dramatic revolutionary period in English unionism..."[8] of roughly the late 1820s, the 1830s and the 1840s. He traced both the industrial and the revolutionary impulses through various union movements ever since.

From the Knights of Labor to the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), with all of the industrial unions and federations in between, the nature of union organization has been in contention for a very long time, and the philosophies of industrial unionism are inter-related. The Western Federation of Miners (WFM) was inspired by the industrial unionism example of the American Railway Union (ARU). Labor Historian Melvyn Dubofsky traces the birth of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) to the industrial unionism of the Western Federation of Miners, and their years under fire during the Colorado Labor Wars.[9] And James P. Cannon has observed that "the CIO became possible only after and because the IWW had championed and popularized the program of industrial unionism in word and deed."[10] As we shall see below, unionism that dares to be powerful invites burgeoning challenges from other powerful interests.

History of industrial unionism

Organizational philosophies for the labor movement grow out of observation and experimentation. Success and failure combine with the aspirations and needs of working people and, in many cases, with the role of government to determine which union concepts will flourish, and which will be abandoned.

Mass organization displaced

The Knights of Labor (KOL) was a mass organization, embracing nearly any worker who wanted to join. An early advocate of producerism, the KOL was so loosely organized that it admitted physicians and employers.[11]

The evolution and competition of labor organizations is quite complex, and there are many factors beyond philosophy or specific organizational structure that determine success or failure. The KOL's policies on a number of issues seemed more progressive than those of the AFL—organizing unskilled workers, educating against discrimination, and a dedication to broad idealism.[12] The KOL subordinated separate craft interests to the welfare of all the workers.[13]

The KOL had an enormous membership compared to the early AFL.[14] The KOL primarily consisted of previously unorganized semi-skilled workmen and machine operators.[15] During 1886 KOL membership grew from 15,000 members to 700,000.[15]

But the AFL seemed more in touch with some of the goals of working people. The KOL began to falter when its leadership appeared to be out of touch with those goals. For example, the AFL supported the eight-hour day. Although the Knights supported the concept in their constitution,[14] they failed to provide a plan for its implementation.[16] Perhaps in part because employers were accepted into the KOL, leadership of the Knights considered a shorter workday impractical. The KOL leadership tried fruitlessly to discourage members from supporting the eight-hour movement that was embraced by the AFL.[17] In its declining years, the remaining KOL membership was primarily rural and middle class.[15]

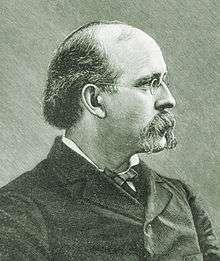

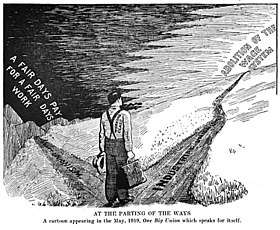

Ascendance of a craft union federation

The American Federation of Labor (AFL) under the leadership of Samuel Gompers focused on "pure and simple" trade unionism. The AFL concerned itself with a "philosophy of pure wage consciousness", according to Selig Perlman,[18] who developed the "business unionism" theory of labor. Perlman saw craft organizing as a means of resisting the encroachment of waves of immigrants. Organization that was based upon craft skills granted control over access to the job.[19] In a sense, craft unions provided a good defense for the privileges of membership, but the offensive power of craft unions to effect change in society at large has been circumscribed by a self-limiting vision. The AFL was businesslike and pragmatic, adopting the motto, "A fair day's wage for a fair day's work."[20]

The early rationale for craft unionism was that solidarity among diverse workers seemed difficult to obtain, while the AFL believed that skilled workers could more easily get improved conditions for themselves.[21] Thus, craft unions have been criticized as a labor elite.

Many Black workers never had the opportunity to learn a skill, and most AFL unions did not organize unskilled workers.[22] Not only did many AFL unions exclude Black workers[23] or relegate them into separate organizations, different groups of Asian immigrants had been excluded for decades. In May 1905 the Asiatic Exclusion League was organized to propagandize against Asian immigration, with many unions participating.

The AFL frequently enforced its agenda upon its member unions with an imposed exclusivity. For example, the United Brewery Workmen (UBW) was affiliated with both the AFL and the Knights of Labor (KOL) from 1893 to 1896. Their purpose in dual affiliation was increasing the breadth of the boycott, which they had found a useful weapon. The AFL threatened to revoke the charter of the national UBW, and they withdrew from the KOL, while urging their individual members to keep their membership in the KOL.[24]

When possible, the AFL forced industrial unions to break up into craft unions, dividing their memberships into exclusive groups with individual contracts. One example was the Amalgamated Association of Street Car Employees (AASCE) in 1912 which, with the aid of Cyrus S. Ching as company negotiator for Boston's public transit system, reached a system-wide agreement for all transit workers. But the AFL and its building trades affiliates were not happy with such an arrangement. Ching, AFL President Samuel Gompers, and International President William D. Mahon of the AASCE, held conferences in which the AASCE ceded jurisdiction over carpenters, painters, electricians, and other skilled trades. The union's membership was divided into 34 distinct labor units, each with a separate agreement.[25]

Having experienced such a breakout into separate labor classifications at Boston transit, Ching opposed such a concept when he became director of industrial relations for the United States Rubber Company. According to economic analyst A. H. Raskin, Ching recognized "that the AFL's commitment to craft delimitation provided poor protection for the welfare of workers in a mass production industry like rubbermaking, which operated along industrial, rather than craft, lines."[25]

Before Herbert Hoover became president, he befriended AFL President Gompers. Hoover, as the former United States Food Administrator, president of the Federated Engineering Societies, and then Secretary of Commerce in the Harding Cabinet in 1921, invited the heads of several "forward-looking" major corporations to meet with him.

[Hoover] asked these men why their companies didn't sit down with Gompers and try to work out an amicable relationship with organized labor. Such a relationship, in Hoover's opinion, would be a bulwark against the spread of radicalism reflected in the rise of the "Wobblies," the Industrial Workers of the World. The Hoover initiative got no encouragement from those at the meeting. The obstacles that Hoover did not comprehend, [Cyrus] Ching recorded in his memoir, were that Gompers had no standing in the affairs of any company except to the extent that AFL unions had organized the workers, and that the federation's focus on craft unionism precluded any effective organization of the mass-production industries by [the AFL's] affiliates.[25]

Industrial unionism as rejection of craft unionism

Six weeks after formation of the Asiatic Exclusion League, the Industrial Workers of the World was formed in Chicago, created as a rejection of the narrow craft unionism philosophy of the AFL. From its inception, the IWW would organize without regard to sex, skills, race, creed, or national origin.[26]

An outgrowth of the struggles of the Western Federation of Miners (WFM), the IWW also adopted the WFM's description of the AFL as the "American Separation of Labor".[27] While the IWW shared the concept of a mass-oriented labor movement—what the IWW would call One Big Union—with the Knights of Labor,[19] the idea of workers having much in common with employers was discarded by the IWW, whose Preamble declares that "the working class and the employing class have nothing in common."[28]

According to Eugene V. Debs, "seasoned old unionists" recognized in 1905 that working people could not win with the labor movement they had. Among the critiques of the AFL were organized scabbery of one union on another, jurisdictional squabbling, an autocratic leadership,[29] and a relationship between union leaders and millionaires in the National Civic Federation that was altogether too cozy. IWW leaders believed that in the AFL there was too little solidarity, and too little "straight" labor education. These circumstances led to too little appreciation of what could be won, and too little will to win it.[30]

For many, organizing industrially is seen as conferring a more powerful structural base from which to challenge employers. Yet this very power has sometimes prompted governments to act as a counterweight to maintain the existing power relationships in society. There are historical examples.

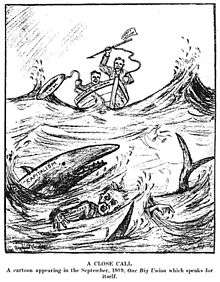

Eugene Debs formed the American Railway Union (ARU) as an industrial organization in response to craft limitations. Railroad engineers and firemen had called a strike, but other employees, particularly conductors who were organized into a different craft, did not join that strike. The conductors piloted scab engineers on the train routes, helping their employers to break the strike.[31] In June 1894, the newly formed, industrially organized ARU voted to join in solidarity with an ongoing strike against the Pullman company. The sympathy strike demonstrated the enormous power of united action, yet resulted in a decisive government response to end the strike and destroy the union.

Within hours of the ARU lending support to the boycott, Pullman traffic ceased to move from Chicago to the West. The boycott then spread to the South and the East.

A statement was issued by the chairman of the General Managers Association, a "half-secret combination of twenty-four railroads centering on Chicago," which acknowledged the power of industrial unionism:

We can handle the railway brotherhoods, but we cannot handle the A.R.U.... We cannot handle Debs. We have got to wipe him out.[32]

The General Managers turned to the federal government, which immediately sent federal troops and United States Marshals to force an end to the strike.

One union leader who closely observed the experiences of the ARU was Big Bill Haywood, who became the powerful secretary treasurer of the Western Federation of Miners (WFM). Haywood had long been a critic of the craft unionism of the AFL, and applied the industrial unionism critique to the railway brotherhoods — closely associated as they were with the AFL — in a strike called by his own miner's union.

The WFM had sought to extend the benefits of union to mill workers who processed the ore dug by miners. Miners and mill workers walked out to support the organizing drive. The 1903-04 Cripple Creek strike was defeated when unionized railroad workers continued to haul ore from the mines to the mills, in spite of strike breakers having been introduced at mine and at mill. "The railroaders form the connecting link in the proposition that is scabby at both ends," Haywood wrote. "This fight, which is entering its third year, could have been won in three weeks if it were not for the fact that the trade unions are lending assistance to the mine operators."[33]

A craft unionist might argue the miners would have been better off sticking to their own business. After all, both the miner's union and the fledgling mill worker's unions had been destroyed. But Haywood took away from this experience the conviction that labor needed more, not less, industrial unionism. The miners had struck in sympathy with the smeltermen, but other unions—notably, craft unions—had not.[34]

Haywood went on to help organize the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), which was itself injured by government action during and after World War I.

In 1912, William E. Bohn was able to predict about the two foremost examples of industrial unionism then extant, "It is possible that neither the Industrial Workers of the World nor the Detroit I. W. W. will ever become numerically important. But the principle of industrial unionism is becoming increasingly a power in the land."[35] While the IWW was debilitated by government repression and a serious 1924 split, and the Detroit IWW simultaneously ceased to exist, the more basic principles of industrial unionism were adopted by the very successful CIO in the 1930s.

Companies prefer to be organized by craft unions

Many companies prefer no union whatsoever. However, when given the choice of an industrial union or a craft union, companies appear to prefer organization by craft unions. As an example, after the American Railway Union was destroyed, Eugene Debs, who had read Marx while serving his sentence, turned to politics, seeking solutions to the problems of working people through socialism.[36] Some railroad workers in Indiana, Kansas, and Illinois who had been a part of Debs' ARU in 1894 resented the fact that Debs turned to socialism for,

...[Debs] had left them without a fighting industrial union and forced them to enter the scab craft movements after he changed the ARU to a political movement...[37]

There was an effort to establish a new industrial union to take the place of the railroad brotherhoods. The United Brotherhood of Railway Employees (UBRE) was formed, with George Estes as president. Estes came from a faction of the Order of Railroad Telegraphers. The UBRE came to public notice when it conducted a moderately successful strike in Manitoba in 1902.[38]

Like the General Managers Association of Chicago, the Southern Pacific Railroad (SPR) acknowledged the danger in allowing railway workers to form an industrial union. The SPR hired the Pinkerton Agency to infiltrate and destroy the UBRE. One of the Pinkerton labor spy tactics was persuading workers to quit the industrial union and instead join a craft union.[39] The defeat of the UBRE ended the last major attempt to organize North American railway workers into an industrial union.[38]

Scranton Declaration and isolation of industrial unions

In 1904 the largest industrial union organization, the Western Federation of Miners, was under significant pressure from employer association attacks and the use of military force in Colorado. The WFM's labor federation, the American Labor Union had not gained significant membership. The AFL was the largest organized labor federation, and the UBRE felt isolated. When they applied to the AFL for a charter, the Scranton Declaration of 1901 was the AFL's guiding principle.[40]

Gompers had promised that each trade and craft would have its own union. The Scranton Declaration acknowledged that one affiliate, the United Mine Workers was formed as an industrial union, but that other skilled trades—carpenters, machinists, etc.—were organized as powerful craft unions. These craft unions refused to allow any encroachment upon their "turf" by the heretical industrial unionists. This concept came to be known as voluntarism. The federation turned the UBRE down in accord with the voluntarism principle. The Scranton Declaration acknowledging voluntarism was adhered to, even though the craft-based railroad brotherhoods had not yet joined the AFL.[41] The AFL was holding the door open for craft unions that might join, and slamming it in the face of the industrial unions who wanted to join. The following year the two thousand member UBRE joined the organizing convention of the IWW.

Craft union federation adopting an industrial union concept

The craft-based AFL had been slow to organize industrial workers, and the federation remained steadfastly committed to craft unionism. This changed in the mid-1930s when, after passage of the National Labor Relations Act, workers began to clamor for union membership. In competition with the CIO movement, the AFL established Federal Labor Unions (FLUs), which were local industrial unions affiliated directly with the AFL,[42] a concept initially envisioned in the 1886 AFL Constitution. FLUs were conceived as temporary unions, many of which were organized on an industrial basis. In keeping with the craft concept, FLUs were designed primarily for organizing purposes, with the membership destined to be distributed among the AFL's craft unions after the majority of workers in an industry were organized.

Radicalism in the union movement

Eugene Debs' early experience with labor actions convinced him to move from craft unionism to militant industrial unionism. During his six months in prison after the American Railway Union was crushed, he became acquainted with socialist principles.[43]

Ed Boyce of the Western Federation of Miners also embraced industrial unionism, believing, as did Debs, that it had more potential than craft unionism. They likewise recognized that industrial unionism alone could not bring into existence the new society that they envisioned.[43] They, along with the WFM's Bill Haywood and others, were instrumental in launching the Western Labor Union, which soon became the American Labor Union, which in 1905 led the way to the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). Boyce proclaimed that labor must "abolish the wage system which is more destructive of human rights and liberty than any other slave system devised",[44] and the IWW later echoed his words in its Preamble. "The working class and the employing class have nothing in common," the Preamble proclaimed. "There can be no peace so long as hunger and want are found among millions of working people and the few, who make up the employing class, have all the good things of life. Between these two classes a struggle must go on..."[45]

Thus, industrial unionism, guided as it was by socialist promptings, has sometimes been considered a more radical—or even revolutionary—form of unionism (see below.)

The CIO and to a lesser extent, the AFL (which was already more conservative) purged themselves of radical members and officers in the years before they merged, as part of what came to be known as the (second) red scare. Some entire unions, perceived by the labor federation leadership as incapable of being reformed, were expelled or replaced.

Revolutionary industrial unionism

Tied closely to the concept of organizing not as a craft, or even as a group of workers with industrial ties, but rather, as a class, is the idea that all of the business world and government, and even the preponderance of the powerful industrial governments of the world, tend to unite to preserve the status quo of the economic system. This encompasses not only the various political systems and the vital question of property rights, but also the relationships between working people and their employers.

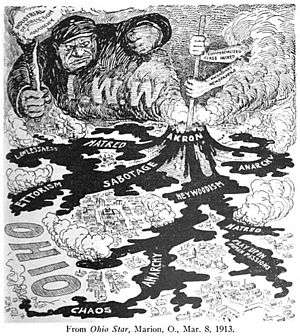

Such tendencies appeared to be in play in 1917, the year of the Russian Revolution. Fred Thompson has written, "Capitalists believed revolution imminent, feared it, legislated against it and bought books on how to keep workers happy."[46] Such instincts also played a role when the governments of fourteen industrialized nations intervened in the civil war that followed the Russian Revolution. Likewise, when the Industrial Workers of the World became the target of government intervention during the period from 1917 to 1921, the governments of the United States, Australia[47] and Canada acted simultaneously.

In the United States, IWW executive board officer Frank Little was lynched from a railroad trestle.[48] Seventeen Wobblies in Tulsa were beaten by a mob and driven out of town.[48] In the third quarter of 1917, the New York Times ran sixty articles attacking the IWW.[48] The Justice Department launched raids on IWW headquarters across the country.[48] The New-York Tribune suggested that the IWW was a German front, responsible for acts of sabotage throughout the nation.[48]

Writing in 1919, Paul Brissenden quoted an IWW publication in Sydney, Australia:

All the machinery of the capitalist state has been turned against us. Our hall has been raided periodically as a matter of principle, our literature, our papers, pictures, and press have all been confiscated; our members and speakers have been arrested and charged with almost every crime on the calendar; the authorities are making unscrupulous, bitter and frantic attempts to stifle the propaganda of the I.W.W.[49]

Brissenden also recorded that

...several laws have been enacted which have been more or less directly aimed at the Industrial Workers of the World. Australia led off with the "Unlawful Associations Act" passed by the House of Representatives of the Commonwealth in December, 1916. (Reported in the New York Times, December 20, 1916, p. s, col. 2. Cf. infra, p. 341.) Within three months of the passage of the Australian Act, the American States of Minnesota and Idaho passed laws "defining criminal syndicalism and prohibiting the advocacy thereof." In February, 1918, the Montana legislature met in extraordinary session and enacted a similar statute.

At Sacramento, on January 16, 1919, according to daily press reports, all of the 46 defendants in the California I.W.W. conspiracy case tried there in the Federal District Court were found guilty of conspiring to violate the Constitution of the United States and the Espionage Act and with attempting to obstruct the war activities of the Government. All of the defendants were members—or alleged members—of the I.W.W. and the case is similar to the one tried in Chicago in 1918. On January 17 Judge Rudkin is reported to have sentenced 43 of the defendants to prison terms of from one to ten years (New York Times, January 17 and 18, 1919).[50]

In essence, the lesson learned is that governments will use legislative and judicial means to thwart attempts to change the economic system, even when conducted by non-violent means. Therefore, in order to significantly improve the status of working people who sell their labor—according to this belief—no less than organizing as an entire class of workers can accomplish and sustain the necessary change.

While Brissenden notes that IWW coal miners in Australia successfully used direct action to free imprisoned strike leaders and to win other demands, Wobbly opposition to conscription during World War I "became so obnoxious" to the Australian government that laws were passed which "practically made it a criminal offense to be a member of the I.W.W."[51]

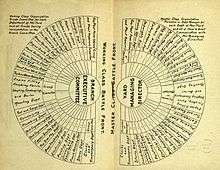

From its first convention in Chicago in 1905, the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) clearly stated its philosophy and its goals: rather than accommodating capitalism, the IWW sought to overthrow it. The IWW organized more broadly than did the CIO or the Knights of Labor. The IWW sought to unite the entire working class into One Big Union which would struggle for improved working conditions and wages in the short term, while working to ultimately overthrow capitalism through a general strike, after which the members of the union would manage production.

One Big Union

Historically, industrial unionism has frequently been associated with the concept of One Big Union (OBU). On July 12, 1919, The New England Worker published "The Principle of Industrial Union":

The principle on which industrial unionism takes its stand is the recognition of the never ending struggle between the employers of labor and the working class. [The industrial union] must educate its members to a complete understanding of the principles and causes underlying every struggle between the two opposing classes. This self-imposed drill, discipline and training will be the methods of the O. B. U.[52]

In short the Industrial Union, is bent upon forming one grand united working class organization and doing away with all the divisions that weaken the solidarity of the workers to better their conditions.[52]

Revolutionary Industrial Unionism, that is the proposition that all wage workers come together in organization according to industry; the groupings of the workers in each of the big divisions of industry as a whole into local, national, and international industrial unions; all to be interlocked, dovetailed, welded into One Big Union for all wage workers; a big union bent on aggressively forging ahead and compelling shorter hours, more wages and better conditions in and out of the work shop... until the working class is able to take possession and control of the machinery, premises, and materials of production right from the capitalists' hands...[52]

Political parties and industrial unionism

Some political parties also promote industrial unionism, such as the Socialist Labor Party of America, whose early leader Daniel De Leon formulated a form of industrial unionism as the mechanism of government in the SLP's vision of a socialist society, and the British Labour Party which has relations with affiliated trade unions.

Industrial unionism outside the United States

Australia

Verity Burgmann asserts in Revolutionary industrial unionism that the IWW in Australia provided an alternate form of labour organising, to be contrasted with the Laborism of the Australian Labor Party and the Bolshevik Communism of the Communist Party of Australia. Revolutionary industrial unionism, for Burgmann, was much like revolutionary syndicalism, but focused much more strongly on the centralised, industrial, nature of unionism. Burgmann saw Australian syndicalism, particularly anarcho-syndicalism, as focused on mythic small shop organisation. For Burgmann the IWW's vision was always a totalising vision of a revolutionary society: the Industrial Commonwealth.[53]

The IWW's politics in 2007 mirror Burgmann's analysis: the IWW does not proclaim Syndicalism, or Anarchism (despite the large number of anarcho-syndicalist members) but instead advocates Revolutionary Industrial Unionism.

United Kingdom

Marion Dutton Savage associates the spirit of industrial unionism with "the aspiration of workers for the control of industry" inspired by Robert Owen in 1833-34. The Grand National Consolidated Trades Union (GCTU) recruited skilled and unskilled workers from many industries, with membership growing to half a million within a few weeks. Frantic opposition forced the GCTU to collapse after a few months, but the ideals of the movement lingered for a time. After Chartism failed, British unions began to organize only skilled workers, and began to limit their goals in tacit support of the existing organization of industry.[54]

A new union movement that was "distinctly class conscious and vaguely Socialistic" began to organize unskilled workers in 1889.[55]

Industrial unionism thence proceeded primarily by combining craft unions into industrial formations, rather than through the birth of new industrial organizations. Industrial organizations prior to 1922 included the National Transport Workers' Federation, the National Union of Railwaymen, and the Miners' Federation of Great Britain.[56]

In 1910 Tom Mann went to France and became acquainted with syndicalism. He returned to Britain and helped to organize the Workers' International Industrial Union, which was similar to the IWW from North America.[57]

Korea

The theory and practice of industrial unionism is not confined to the western, English speaking world. The Korean Confederation of Trade Unions (KCTU) is committed to reorganizing their current union structure along the lines of industrial unionism.[58]

South Africa

The Congress of South African Trade Unions (COSATU) is also organized along the lines of industrial unionism.[59]

See also

- Labor federation competition in the U.S.

Notes

- Savage 1922, p. 3.

- Savage 1922, pp. 19–21.

- Savage 1922, p. 21.

- Savage 1922, pp. 21–22.

- Savage 1922, p. 4.

- Savage 1922, pp. 4–5.

- Savage 1922, pp. 22–24.

- Brissenden 1919, p. 27.

- Dubofsky 1987, pp. 20, 33.

- Cannon 1955.

- Cahn 1972, p. 137. The question of admitting physicians is disputed—for example, "no... doctor... could be admitted", Rayback 1966, p. 145.

- Cahn 1972, pp. 137, 160.

- Savage 1922, p. 15.

- Rayback 1966, p. 145.

- Savage 1922, p. 16.

- Grob 1961, p. 74.

- Cahn 1972, pp. 139–140.

- Cahn 1972, p. 137.

- Fusfeld 1985, pp. 6–7.

- Cahn 1972, pp. 137, 139.

- Savage 1922, p. 19.

- Cahn 1972, p. 231.

- Cahn 1972, p. 160.

- Thompson & Murfin 1976, p. 8.

- Raskin 1989.

- Solidarity Forever—An oral history of the IWW, Stewart Bird, Dan Georgakas, Deborah Shaffer, 1985, page 140.

- Cahn 1972, p. 201.

- Constitution and By-Laws of the Industrial Workers of the World, Preamble, 1905, http://www.workerseducation.org/crutch/constitution/1905const.html Retrieved April 19, 2007.

- Brissenden 1919, p. 87.

- Thompson & Murfin 1976, p. 5.

- Brissenden 1919, p. 86.

- Rayback 1966, p. 201.

- Carlson 1983, p. 80.

- Carlson 1983, p. 79.

- Bohn 1912.

- Cahn 1972, p. 177.

- Thompson & Murfin 1976, p. 6, quoting Pinkerton in Daily People, November 4, 1906.

- Tuck 1983.

- Friedman 1907, p. 189.

- Thompson & Murfin 1976, p. 7.

- Thompson & Murfin 1976, pp. 7–8.

- Cahn 1972, pp. 253–254.

- Dubofsky 2000, p. 36.

- Dubofsky 2000, p. 40.

- Preamble to the Constitution, Industrial Workers of the World, 1905, http://www.workerseducation.org/crutch/constitution/1905const.html retrieved March 12, 2011

- Thompson & Murfin 1976, p. 127.

- The Autobiography of Big Bill Haywood, 1929, pp. 297 ppbk.

- Starr 1997, p. 48.

- Brissenden 1919, p. 340, quoting a March 17, 1917 Solidarity reprint of Direct Action (Sydney).

- Brissenden 1919, p. 280.

- Brissenden 1919, pp. 341–342.

- Daniel Bloomfield, Selected Articles on Modern Industrial Movements, H.W. Wilson Co., 1919, pages 39–40.

- Burgmann 1995.

- Savage 1922, p. 6.

- Savage 1922, pp. 6–7.

- Savage 1922, pp. 7–8.

- Savage 1922, pp. 13–14.

- This is KCTU, Building Industrial Unionism http://kctu.org/2003/html/sub_01.php

- About Cosatu, One industry, one union - one country, one federation "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2007-12-12. Retrieved 2007-11-30.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

References

- Bohn, William E. (1912). "The Industrial Workers of the World". The Survey: Social, Charitable, Civic: A Journal of Constructive Philanthropy. New York: The Charity Organization Society. 28: 220–225. Retrieved April 24, 2016.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Brissenden, Paul Frederick (1919). The I.W.W.: A Study of American Syndicalism. New York: Columbia University. Retrieved April 23, 2016.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Burgmann, Verity (1995). Revolutionary Industrial Unionism: The Industrial Workers of the World in Australia. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-47123-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cahn, William (1972). A Pictorial History of American Labor: The Contributions of the Working Man and Woman to America's Growth, from Colonial Times to Present. New York: Crown Publishers. ISBN 978-0-517-50040-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cannon, James P. (1955). "The I.W.W." (PDF). Fourth International. New York: Fourth International Publishing Association. 16 (3): 75–86. Retrieved April 26, 2016.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Carlson, Peter (1983). Roughneck: The Life and Times of Big Bill Haywood. New York: W. W. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-01621-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dubofsky, Melvyn (1987). 'Big Bill' Haywood.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- — (2000). McCartin, Joseph A. (ed.). We Shall Be All: A History of the Industrial Workers of the World. The Working Class in American History (abridged ed.). Urbana: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-06905-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Friedman, Morris (1907). The Pinkerton Labor Spy. New York: Wilshire Book Co. Retrieved April 23, 2016.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fusfeld, Daniel R. (1985). The Rise and Repression of Radical Labor. Chicago: Charles H. Kerr Publishing Company.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Grob, Gerald N. (1961). Workers and Utopia: A Study of Ideological Conflict in the American Labor Movement, 1865–1900. Northwestern University Studies in History. 2. Evanston, Illinois: Northwestern University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Raskin, A. H. (1989). "Cyrus S. Ching: Pioneer in Industrial Peacemaking" (PDF). Monthly Labor Review. Washington: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. 112 (8): 22–35. Retrieved April 23, 2016.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rayback, Joseph G. (1966). A History of American Labor. New York: Free Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Savage, Marion Dutton (1922). Industrial Unionism in America. New York: The Ronald Press Company. Retrieved April 23, 2016.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Starr, Kevin (1997) [1996]. Endangered Dreams: The Great Depression in California. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-511802-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Thompson, Fred W.; Murfin, Patrick (1976). The I.W.W.: Its First Seventy Years, 1905–1975. Chicago: Industrial Workers of the World.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Tuck, J. Hugh (1983). "The United Brotherhood of Railway Employees in Western Canada, 1898–1905". Labour / Le Travail. 11: 63–88. JSTOR 25140201.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)