Anarchism in Germany

German individualist philosopher Max Stirner became an important early influence in anarchism. Afterwards Johann Most became an important anarchist propagandist in both Germany and in the United States. In the late 19th century and early 20th century there appeared individualist anarchists influenced by Stirner such as John Henry Mackay, Adolf Brand and Anselm Ruest (Ernst Samuel) and Mynona (Salomo Friedlaender).

The anarchists Gustav Landauer, Silvio Gesell and Erich Mühsam had important leadership positions within the revolutionary councilist structures during the uprising at the late 1910s known as Bavarian Soviet Republic.[1] During the rise of Nazi Germany, Erich Mühsam was assassinated in a Nazi concentration camp both for his anarchist positions and for his Jewish background.[2] The anarchosyndicalist activist and writer Rudolf Rocker became an influential personality in the establishment of the international federation of anarchosyndicalist organizations called International Workers Association as well as the Free Workers' Union of Germany.

Contemporary German anarchist organizations include the anarchosyndicalist Free Workers' Union and the Federation of German speaking Anarchists (Föderation Deutschsprachiger AnarchistInnen).

Stirner and other pioneers

Anarchist historians often trace the roots of German anarchism back to the 16th century German Peasants' War. On the other hand, both James Joll and George Woodcock hold that this link is exaggerated. Later anarchists have also claimed the liberal thinking of Friedrich Schiller, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, and Heinrich Heine to be the precursors of anarchism.[3]

In the first half of the 19th century, there was no significant anarchist movement in Germany to speak of, but several thinkers influenced by anarchism, particularly by Pierre-Joseph Proudhon. According to Gustav Landauer, the thinking of political satirist Ludwig Börne, though not anarchist, had some parallels to anarchism. Börne once claimed that "freedom arises only out of anarchy—this is our belief, this is the lesson of history." The composer Richard Wagner, though often linked with fascism, sympathized with Mikhail Bakunin. In an article on the March Revolution, which would later be re-printed by the anarchist press, Wagner said that revolution will "destroy the domination of one over many [...] and the power of the Almighty, of law, of property". It was this article that led Max Nettlau to liken Wagner an anarchist during this period.[4]

Several German socialists of this period also exhibited anarchist tendencies. The young Wilhelm Weitling, influenced by both Proudhon and Louis Auguste Blanqui, once wrote that "a perfect society has no government, but only an administration, no laws, but only obligations, no punishment, but means of correction." Moses Hess was also an anarchist until around 1844, disseminating Proudhon's theories in Germany, but would go on to write the anti-anarchist pamphlet Die letzte Philosophie. Karl Grün, well known for his role in the disputes between Marx and Proudhon, held a view Nettlau would liken to communist anarchism while still living in Cologne and then left for Paris, where he became a disciple of Proudhon. Wilhelm Marr, born in Hamburg but primarily active in the Young Germany clubs in Switzerland, edited several antiauthoritarian periodicals. In his book on anarchism Anarchie oder Autorität, he comes to the conclusion that liberty is found only in anarchy.[5]

Edgar Bauer (7 October 1820 – 18 August 1886) was a German political philosopher and a member of the Young Hegelians. According to Lawrence S. Stepelevich, Edgar Bauer was the most anarchistic of the Young Hegelians, and "...it is possible to discern, in the early writings of Edgar Bauer, the theoretical justification of political terrorism."[6] German anarchists such as Max Nettlau and Gustav Landauer credited Edgar Bauer with founding the anarchist tradition in Germany.[7] In 1843 he published a book titled The Conflict of Criticism with Church and State. This caused him to be charged with sedition. He was imprisoned for four years in the fortress at Magdeburg. While he was in prison, his former associates Marx and Engels published a scathing critique of him and his brother Bruno, titled The Holy Family (1844). They resumed the attack in The German Ideology (1846), which was not published at the time.

Max Stirner

Johann Kaspar Schmidt (25 October 1806 – 26 June 1856), better known as Max Stirner (the nom de plume he adopted from a schoolyard nickname he had acquired as a child because of his high brow, in German 'Stirn'), was a German philosopher, who ranks as one of the literary fathers of nihilism, existentialism, post-modernism and anarchism, especially of individualist anarchism. Stirner's main work is The Ego and Its Own, also known as The Ego and His Own (Der Einzige und sein Eigentum in German, which translates literally as The Only One and his Property). This work was first published in 1844 in Leipzig, and has since appeared in numerous editions and translations.

Stirner's philosophy is usually called "egoism". He says that the egoist rejects pursuit of devotion to "a great idea, a good cause, a doctrine, a system, a lofty calling," saying that the egoist has no political calling but rather "lives themselves out" without regard to "how well or ill humanity may fare thereby."[8] Stirner held that the only limitation on the rights of the individual is his power to obtain what he desires.[9] He proposes that most commonly accepted social institutions—including the notion of State, property as a right, natural rights in general, and the very notion of society—were mere spooks in the mind. Stirner wanted to "abolish not only the state but also society as an institution responsible for its members."[10]

Max Stirner's idea of the union of Egoists (German: Verein von Egoisten), was first expounded in The Ego and Its Own. The Union is understood as a non-systematic association, which Stirner proposed in contradistinction to the state.[11] The Union is understood as a relation between egoists which is continually renewed by all parties' support through an act of will.[12] The Union requires that all parties participate out of a conscious egoism. If one party silently finds themselves to be suffering, but puts up and keeps the appearance, the union has degenerated into something else.[12] This union is not seen as an authority above a person's own will. This idea has received interpretations for politics, economic and sex/love.

Stirner claimed that property comes about through might: "Whoever knows how to take, to defend, the thing, to him belongs property." "What I have in my power, that is my own. So long as I assert myself as holder, I am the proprietor of the thing." "I do not step shyly back from your property, but look upon it always as my property, in which I respect nothing. Pray do the like with what you call my property!".[13] His concept of "egoistic property" not only rejects moral restraint on how own obtains and uses things, but includes other people as well.[14]

Although Stirner's philosophy is individualist, it has influenced some libertarian communists and anarcho-communists. "For Ourselves Council for Generalized Self-Management" discusses Stirner and speaks of a "communist egoism," which is said to be a "synthesis of individualism and collectivism," and says that "greed in its fullest sense is the only possible basis of communist society."[15] Forms of libertarian communism such as insurrectionary anarchism are influenced by Stirner.[16][17] Anarcho-communist Emma Goldman was influenced by both Stirner and Peter Kropotkin and blended their philosophies together in her own.[18]

Johann Most

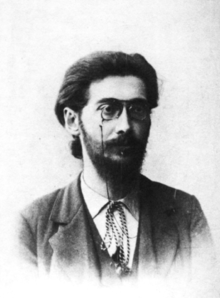

Johann Joseph Most (5 February 1846 in Augsburg, Bavaria – 17 March 1906 in Cincinnati, Ohio) was a German-American politician, newspaper editor, and orator. He is credited with popularizing the concept of "Propaganda of the deed".[19]

As the 1860s drew to a close, Most was won over to the ideas of international socialism, an emerging political movement in Germany and Austria. Most saw in the doctrines of Karl Marx and Ferdinand Lassalle a blueprint for a new egalitarian society and became a fervid supporter of the Social Democracy, as the Marxist movement was known in the day.[20] Most was repeatedly arrested for his attacks on patriotism and conventional religion and ethics, and for his gospel of terrorism, preached in prose and in many songs such as those in his Proletarier-Liederbuch (Proletarian Songbook). Some of his experiences in prison were recounted in the 1876 work, Die Bastille am Plötzensee: Blätter aus meinem Gefängniss-Tagebuch (The Bastille on Plötzensee: Pages from my Prison Diary).

After advocating violent action, including the use of explosive bombs, as a mechanism to bring about revolutionary change, Most was forced into exile by the government. He went to France but was forced to leave at the end of 1878, settling in London. There he founded his own newspaper, Freiheit (Freedom), with the first issue coming off the press dated 4 January 1879.[21] Convinced by his own experience of the futility of parliamentary action, Most began to espouse the doctrine of anarchism, which led to his expulsion from the German Social Democratic Party in 1880.[22] Encouraged by news of labor struggles and industrial disputes in the United States, Most emigrated to the USA upon his release from prison in 1882. He promptly began agitating in his adopted land among other German émigrés. Most resumed the publication of the Freiheit in New York. He was imprisoned in 1886, again in 1887, and in 1902, the last time for two months for publishing after the assassination of President McKinley an editorial in which he argued that it was no crime to kill a ruler. A gifted orator, Most propagated these ideas throughout Marxist and anarchist circles in the United States and attracted many adherents, most notably Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman. Most was in Cincinnati, Ohio to give a speech when he fell ill. Diagnosed with erysipelas, doctors could do little for him, and he died a few days later.

German individualist anarchism

An influential form of individualist anarchism, called "egoism,"[23] or egoist anarchism, was expounded by one of the earliest and best-known proponents of individualist anarchism, the German Max Stirner.[24] Stirner's The Ego and Its Own, published in 1844, is a founding text of the philosophy.[24] According to Stirner, the only limitation on the freedom of the individual is their power to obtain what they desire,[25] without regard for God, state, or morality.[26] To Stirner, rights were spooks in the mind, and he held that society as an abstract whole does not exist but rather "the individuals are its reality".[27] Stirner advocated self-assertion and foresaw unions of egoists, voluntary and non-systematic associations continually renewed by all parties' support through an act of will,[28] which Stirner proposed as a form of organization in place of the state.[11] Egoist anarchists claim that egoism will foster genuine and spontaneous union between individuals.[29] "Egoism" has inspired many interpretations of Stirner's philosophy. It was re-discovered and promoted by German philosophical anarchist and LGBT activist John Henry Mackay.

John Henry Mackay

In Germany the Scottish-born German John Henry Mackay became the most important individualist anarchist propagandist. He fused Stirnerist egoism with the positions of Benjamin Tucker and translated Tucker into German. Two semi-fictional writings of his own Die Anarchisten and Der Freiheitsucher contributed to individualist theory, updating egoist themes with respect to the anarchist movement. His writing were translated into English as well.[30] Mackay is also an important European early activist for LGBT rights.

Adolf Brand

Adolf Brand (1874–1945) was a German writer, Stirnerist anarchist and pioneering campaigner for the acceptance of male bisexuality and homosexuality. Brand published the world's first ongoing homosexual publication, Der Eigene in 1896.[31] The name was taken from Stirner, who had greatly influenced the young Brand, and refers to Stirner's concept of "self-ownership" of the individual. Der Eigene concentrated on cultural and scholarly material, and may have averaged around 1500 subscribers per issue during its lifetime. Contributors included Erich Mühsam, Kurt Hiller, John Henry Mackay (under the pseudonym Sagitta) and artists Wilhelm von Gloeden, Fidus and Sascha Schneider. Brand contributed many poems and articles himself. Benjamin Tucker followed this journal from the United States.[32]

Anselm Ruest (Ernst Samuel) and Mynona (Salomo Friedlaender)

Der Einzige was the title of a German individualist anarchist magazine. It appeared in 1919, as a weekly, then sporadically until 1925 and was edited by cousins Anselm Ruest (pseud. for Ernst Samuel) and Mynona (pseud. for Salomo Friedlaender). Its title was adopted from the book Der Einzige und sein Eigentum (engl. trans. The Ego and Its Own) by Max Stirner. Another influence was the thought of German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche.[33] The publication was connected to the local expressionist artistic current and the transition from it towards dada.[34]

Anarchism in the German Revolution of 1918–1919 and under Nazism

In the German uprising known as the Bavarian Soviet Republic the anarchists Gustav Landauer, Silvio Gesell and Erich Mühsam had important leadership positions within the revolutionary councilist structures.[1] On 6 April 1919, a Soviet Republic was formally proclaimed. Initially, it was ruled by USPD members such as Ernst Toller, and anarchists like Gustav Landauer, Silvio Gesell and Erich Mühsam.

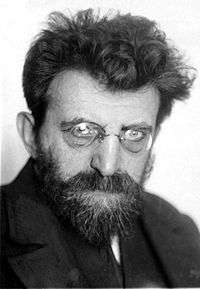

Gustav Landauer

Gustav Landauer (7 April 1870 in Karlsruhe, Baden – 2 May 1919 in Munich, Bavaria) was one of the leading theorists on anarchism in Germany in the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century. He was an advocate of communist anarchism and an avowed pacifist. At the "International Convention of Socialist Workers" of the II. Socialist International in August 1893 in Zurich, Landauer, as a delegate for the Berlin anarchists, stood for an "anarchist socialism". Against an anarchist minority the convention with 411 delegates from 20 countries passed a resolution in favour of participation in elections and political action in parliaments. The anarchists were excluded from the II. Socialist International. From 1909 to 1915 Landauer published the magazine "The Socialist" (Der Sozialist) in Berlin, which was considered to be the mouthpiece of the "Socialist Federation" (Sozialistischer Bund) founded by Landauer in 1908. Among the first members were Erich Mühsam and Martin Buber. When the soviet republic was proclaimed on 7 April 1919 against the elected government of Johannes Hoffmann, Landauer became Commissioner of Enlightenment and Public Instruction. After the City of Munich was reconquered by the German army and Freikorps units, Gustav Landauer was arrested on 1 May 1919 and stoned to death by troopers one day later in Munich's Stadelheim Prison. After the Nazis were elected in Germany in 1933 they destroyed Landauer's grave, which had been erected in 1925, sent his remains to the Jewish congregation of Munich, charging them for the costs. Landauer was later put to rest at the Munich Waldfriedhof (Forest Cemetery)

Landauer supported anarchism already in the 1890s. In those years he was especially enthusiastic about the individualistic approach of Max Stirner. He didn't want to stay behind Stirner's extremely individual approach but wanted to develop a new general public, a unity and community. His "social Anarchism" was a union of individuals on a voluntary basis in small socialist communities which came together freely. Landauer's goal was always emancipation from state, church or other forms of subordination in society. The expression 'Anarchism' stems from the Greek "arche" meaning 'power', 'reign' or 'rule'. Thus 'An-archy' equals 'non-power', 'no-reign' or 'no-rule'. The rejection of the state is common to all Anarchist positions. Some also reject institutions and moral concepts, such as church, matrimony or family; the rejection is, of course, voluntary. Landauer came out against Marxists and Social Democrats, reproaching them for wanting to erect another state executing power. For him Anarchism was a spiritual movement, almost religious. In contrast to other Anarchists he did not reject matrimony; on the contrary, it was a pillar of the community in Landauer's system. True Anarchism results from the "inner segregation" of the individuals. It is exactly this from which one is to be freed. Precondition for autonomy and independence respectively is the "seclusion" which leads to a "Unity with the world". According to Landauer it is necessary to change the nature of man or at least to change his ways, so that finally the inner convictions can appear and be lived. This includes an "Anarchism of deed" that is never strictly theoretical.

Silvio Gesell

.jpg)

Silvio Gesell (17 March 1862 – 11 March 1930) was a German merchant, theoretical economist, social activist, anarchist and founder of Freiwirtschaft. After the bloody end of the Soviet Republic, Gesell was held in detention for several months until being acquitted of treason by a Munich court because of the speech he gave in his own defense. Because of his participation in the Soviet Republic, Switzerland denied him the opportunity to return to his farm in Neuchâtel. Gesell then moved first to Nuthetal, Potsdam-Mittelmark, then back to Oranienburg. After another short stay in Argentina in 1924, he returned to Oranienburg in 1927. Here, he died of pneumonia on 11 March 1930.

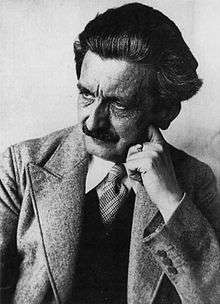

Erich Mühsam

Erich Mühsam (6 April 1878 – 10 July 1934) was a German-Jewish anarchist essayist, poet and playwright. He emerged at the end of World War I as one of the leading agitators for a federated Bavarian Soviet Republic. Also a cabaret performer, he achieved international prominence during the years of the Weimar Republic for works which, before Hitler came to power in 1933, condemned Nazism and satirized the future dictator. Mühsam died in the Oranienburg concentration camp in 1934.

Mühsam moved to Berlin in 1900, where he soon became involved in a group called Neue Gemeinschaft (New Society) under the direction of Julius and Heinrich Hart which combined socialist philosophy with theology and communal living in the hopes of becoming "a forerunner of a socially united great working commune of humanity." Within this group, Mühsam became acquainted with Gustav Landauer who encouraged his artistic growth and compelled the young Mühsam to develop his own activism based on a combination of communist and anarchist political philosophy that Landauer introduced to him. Desiring more political involvement, in 1904, Mühsam withdrew from Neue Gemeinschaft and relocated temporarily to an artists commune in Ascona, Switzerland where vegetarianism was mixed with communism and socialism. In 1911, Mühsam founded the newspaper, Kain (Cain), as a forum for communist-anarchist ideologies, stating that it would "be a personal organ for whatever the editor, as a poet, as a citizen of the world, and as a fellow man had on his mind." Mühsam used Kain to ridicule the German state and what he perceived as excesses and abuses of authority, standing out in favour of abolishing capital punishment, and opposing the government's attempt at censoring theatre, and offering prophetic and perceptive analysis of international affairs. For the duration of World War I, publication was suspended to avoid government-imposed censorship often enforced against private newspapers that disagreed with the imperial government and the war.

In 1926, Mühsam founded a new journal which he called Fanal (The Torch), in which he openly and precariously criticized the communists and the far Right-wing conservative elements within the Weimar Republic. During these years, his writings and speeches took on a violent, revolutionary tone, and his active attempts to organize a united front to oppose the radical Right provoked intense hatred from conservatives and nationalists within the Republic. Mühsam specifically targeted his writings to satirize the growing phenomenon of Nazism, which later raised the ire of Adolf Hitler and Joseph Goebbels. Die Affenschande (1923), a short story, ridiculed the racial doctrines of the Nazi party, while the poem Republikanische Nationalhymne (1924) attacked the German judiciary for its disproportionate punishment of leftists while barely punishing the right wing participants in the Putsch.

Mühsam was arrested on charges unknown in the early morning hours of 28 February 1933, within a few hours after the Reichstag fire in Berlin. Joseph Goebbels, the Nazi propaganda minister, labelled him as one of "those Jewish subversives." It is alleged that Mühsam was planning to flee to Switzerland within the next day. Over the next seventeen months, he would be imprisoned in the concentration camps at Sonnenburg, Brandenburg and finally, Oranienburg. On 2 February 1934, Mühsam was transferred to the concentration camp at Oranienburg. The beatings and torture continued, until finally on the night of 9 July 1934, Mühsam was tortured and murdered by the guards, his battered corpse found hanging in a latrine the next morning.[2] An official Nazi report dated 11 July stated that Erich Mühsam committed suicide, hanging himself while in "protective custody" at Oranienburg. However, a report from Prague on 20 July 1934 in The New York Times stated otherwise

- "His widow declared this evening that, when she was first allowed to visit her husband after his arrest, his face was so swollen by beating that she could not recognise him. He was assigned to the task of cleaning toilets and staircases and Storm Troopers amused themselves by spitting in his face, she added. On 8 July, last, she saw him for the last time alive. Despite the tortures he had undergone for fifteen months, she declared, he was cheerful, and she knew at once when his "suicide" was reported to her three days later that it was untrue. When she told the police that they had "murdered" him, she asserted they shrugged their shoulders and laughed. A post mortem examination was refused, according to Frau Mühsam, but Storm Troopers, incensed with their new commanders, showed her the body which bore unmistakable signs of strangulation, with the back of the skull shattered as if Herr Mühsam had been dragged across the parade ground."[35]

Rudolf Rocker, German anarchosyndicalism and World War II

Rudolf Rocker returned to Germany in November 1918 upon an invitation from Fritz Kater to join him in Berlin to re-build the Free Association of German Trade Unions (FVdG). The FVdG was a radical labor federation that quit the SPD in 1908 and became increasingly syndicalist and anarchist. During World War I, it had been unable to continue its activities for fear of government repression, but remained in existence as an underground organization.[36] Rocker was opposed to the FVdG's alliance with the communists during and immediately after the November Revolution, as he rejected Marxism, especially the concept of the dictatorship of the proletariat. Soon after arriving in Germany, however, he once again became seriously ill. He started giving public speeches in March 1919, including one at a congress of munitions workers in Erfurt, where he urged them to stop producing war material. During this period the FVdG grew rapidly and the coalition with the communists soon began to crumble. Eventually all syndicalist members of the Communist Party were expelled. From 27 to 30 December 1919, the twelfth national congress of the FVdG was held in Berlin. The organization decided to become the Free Workers' Union of Germany (FAUD) under a new platform, which had been written by Rocker: the Prinzipienerklärung des Syndikalismus (Declaration of Syndicalist Principles). It rejected political parties and the dictatorship of the proletariat as bourgeois concepts. The program only recognized de-centralized, purely economic organizations. Although public ownership of land, means of production, and raw materials was advocated, nationalization and the idea of a communist state were rejected. Rocker decried nationalism as the religion of the modern state and opposed violence, championing instead direct action and the education of the workers.[37]

On Gustav Landauer's death during the Munich Soviet Republic uprising, Rocker took over the work of editing the German publications of Kropotkin's writings. In 1920, the social democratic Defense Minister Gustav Noske started the suppression of the revolutionary left, which led to the imprisonment of Rocker and Fritz Kater. During their mutual detainment, Rocker convinced Kater, who had still held some social democratic ideals, completely of anarchism.[38]

In the following years, Rocker became one of the most regular writers in the FAUD organ Der Syndikalist. In 1920, the FAUD hosted an international syndicalist conference, which ultimately led to the founding of the International Workers Association (IWA) in December 1922. Augustin Souchy, Alexander Schapiro, and Rocker became the organization's secretaries and Rocker wrote its platform. In 1921, he wrote the pamphlet Der Bankrott des russischen Staatskommunismus (The Bankruptcy of Russian State Communism) attacking the Soviet Union. He denounced what he considered a massive oppression of individual freedoms and the suppression of anarchists starting with a purge on 12 April 1918. He supported instead the workers who took part in the Kronstadt uprising and the peasant movement led by the anarchist Nestor Makhno, whom he would meet in Berlin in 1923. In 1924, Rocker published a biography of Johann Most called Das Leben eines Rebellen (The Life of a Rebel). There are great similarities between the men's vitas. It was Rocker who convinced the anarchist historian Max Nettlau to start publication of his anthology Geschichte der Anarchie (History of Anarchy) in 1925.[39]

During the mid-1920s, the decline of Germany's syndicalist movement started. The FAUD had reached its peak of around 150,000 members in 1921, but then started losing members to both the Communist and the Social Democratic Party. Rocker attributed this loss of membership to the mentality of German workers accustomed to military discipline, accusing the communists of using similar tactics to the Nazis and thus attracting such workers. At first only planning a short book on nationalism, he started work on Nationalism and Culture, which would be published in 1937 and become one of Rocker's best-known works, around 1925. 1925 also saw Rocker visit North America on a lecture tour with a total of 162 appearances. He was encouraged by the anarcho-syndicalist movement he found in the US and Canada.[40]

Returning to Germany in May 1926, he became increasingly worried about the rise of nationalism and fascism. He wrote to Nettlau in 1927: "Every nationalism begins with a Mazzini, but in its shadow there lurks a Mussolini". In 1929, Rocker was a co-founder of the Gilde freiheitlicher Bücherfreunde (Guild of Libertarian Bibliophiles), a publishing house which would release works by Alexander Berkman, William Godwin, Erich Mühsam, and John Henry Mackay. In the same year he went on a lecture tour in Scandinavia and was impressed by the anarcho-syndicalists there. Upon return, he wondered whether Germans were even capable of anarchist thought. In the 1930 elections, the Nazi Party received 18.3% of all votes, a total of 6 million. Rocker was worried: "Once the Nazis get to power, we'll all go the way of Landauer and Eisner" (who were killed by reactionaries in the course of the Munich Soviet Republic uprising).[41]

After the Reichstag fire on 27 February, Rocker and Witkop decided to leave Germany. As they left they received news of Erich Mühsam's arrest. After his death in July 1934, Rocker would write a pamphlet called Der Leidensweg Erich Mühsams (The Life and Suffering of Erich Mühsam) about the anarchist's fate. Rocker reached Basel, Switzerland on 8 March by the last train to cross the border without being searched. Two weeks later, Rocker and his wife joined Emma Goldman in St. Tropez, France. There he wrote Der Weg ins Dritte Reich (The Path to the Third Reich) about the events in Germany, but it would only be published in Spanish.[42]

In May, Rocker and Witkop moved back to London. There Rocker was welcomed by many of the Jewish anarchists he had lived and fought alongside for many years. He held lectures all over the city. In July, he attended an extraordinary IWA meeting in Paris, which decided to smuggle its organ Die Internationale into Nazi Germany.[43] In 1937, Nationalism and Culture, which he had started work on around 1925, was finally published with the help of anarchists from Chicago Rocker had met in 1933. A Spanish edition was released in three volumes in Barcelona, the stronghold of the Spanish anarchists. It would be his best-known work.[44] In 1938, Rocker published a history of anarchist thought, which he traced all the way back to ancient times, under the name Anarcho-Syndicalism. A modified version of the essay would be published in the Philosophical Library series European Ideologies under the name Anarchism and Anarcho-Syndicalism in 1949.[45]

Post-war and contemporary times

After World War II, an appeal in the Fraye Arbeter Shtime detailing the plight of German anarchists and called for Americans to support them. By February 1946, the sending of aid parcels to anarchists in Germany was a large-scale operation. In 1947, Rocker published Zur Betrachting der Lage in Deutschland (Regarding the Portrayal of the Situation in Germany) about the impossibility of another anarchist movement in Germany. It became the first post-World War II anarchist writing to be distributed in Germany. Rocker thought young Germans were all either totally cynical or inclined to fascism and awaited a new generation to grow up before anarchism could bloom once again in the country. Nevertheless, the Federation of Libertarian Socialists (FFS) was founded in 1947 by former FAUD members. Rocker wrote for its organ, Die Freie Gesellschaft, which survived until 1953.[46] In 1949, Rocker published another well-known work. On 10 September 1958, Rocker died in the Mohegan Colony.

Graswurzelrevolution (German for "grassroots revolution") is an anarcho-pacifist magazine founded in 1972 by Wolfgang Hertle in West Germany. It focuses on social equality, anti-militarism and ecology. The magazine is considered the most influential and long-lived anarchist publication of the German post-war period. The zero issue of graswurzelrevolution (GWR) [Grass Roots Revolution] was published in the summer of 1972 in Augsburg, Bavaria. The "monthly magazine for a non-violent, anarchist society" was inspired by "Peace News" (published since 1936 by War Resisters International (WRI) in London), the German-speaking "Direkte Aktion" ("newspaper for anarchism and non-violence"; published from 1965 to 1966 by Wolfgang Zucht and other non-violent activists in Hanover) and the French-speaking "Anarchisme et Nonviolence" (published in Switzerland and France from 1964 to 1973).[47]

The Free Workers' Union (German: Freie Arbeiterinnen- und Arbeiter-Union[48] or Freie ArbeiterInnen-Union; abbreviated FAU) is a small anarcho-syndicalist union in Germany. It is the German section of the International Workers Association (IWA), to which the larger and better known Confederación Nacional del Trabajo in Spain also belongs. Because of their membership in the IWA the name is also often abbreviated as FAU-IAA or FAU/IAA.[49] he FAU sees itself in the tradition of the Free Workers' Union of Germany (German: Freie Arbeiter Union Deutschlands; FAUD), the largest anarcho-syndicalist union in Germany until it disbanded in 1933 in order to avoid repression by the nascent National Socialist regime, and to illegally organize resistance against it. The FAU was then founded in 1977 and has grown consistently all through the 1990s. Now, the FAU consists of just under 40 groups, organized locally and by branch of trade. Because it rejects hierarchical organizations and political representation and believes in the concept of federalism, most of the decisions are made by the local unions. The federalist organization exists in order to coordinate strikes, campaigns and actions and for communication purposes. There are 800–1000 members organized in the various local unions. The FAU publishes the bimonthly anarcho-syndicalist newspaper Direkte Aktion as well as pamphlets on current and historical topics. Because it supports the classical concept of the abolition of the wage system, the FAU is observed by the Bundesamt für Verfassungsschutz (Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution).

The Federation of German speaking Anarchists (Föderation Deutschsprachiger AnarchistInnen) is a synthesist anarchist federation of German speaking countries which is affiliated with the International of Anarchist Federations.[50]

References

- "The Munich Soviet (or "Council Republic") of 1919 exhibited certain features of the TAZ, even though – like most revolutions – its stated goals were not exactly "temporary." Gustav Landauer's participation as Minister of Culture along with Silvio Gesell as Minister of Economics and other anti-authoritarian and extreme libertarian socialists such as the poet/playwrights Erich Mªhsam and Ernst Toller, and Ret Marut (the novelist B. Traven), gave the Soviet a distinct anarchist flavor." Hakim Bey. "T.A.Z.: The Temporary Autonomous Zone, Ontological Anarchy, Poetic Terrorism"

- Mühsam, Erich (2001). David A. Shepherd (ed.). Thunderation!/Alle Wetter!: Folk Play With Song and Dance/Volksstuck Mit Gesang Und Tanz. Bucknell University Press. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-8387-5416-0.

- Carlson 1972, pg. 13.

- Carlson 1972, pg. 13–17

- Carlson 1972, pg. 22–30.

- Stepelevich, Lawrence S. (1983). The Young Hegelians: An Anthology. Cambridge

- Cp. Nettlau, M., Der Vorfrühling der Anarchie. Berlin, 1925, p. 178. Landauer, G., "Zur Geschichte des Wortes Anarchie." In: Der Sozialist, 1 June 1909.

- Moggach, Douglas. The New Hegelians. Cambridge University Press, 2006 p. 183

- The Encyclopedia Americana: A Library of Universal Knowledge. Encyclopedia Corporation. p. 176

- Heider, Ulrike. Anarchism: Left, Right and Green, San Francisco: City Lights Books, 1994, pp. 95–96

- Thomas, Paul (1985). Karl Marx and the Anarchists. London: Routledge/Kegan Paul. pp. 142. ISBN 0-7102-0685-2.

- Nyberg, Svein Olav, "The union of egoists" (PDF), Non Serviam, Oslo, Norway: Svein Olav Nyberg, 1: 13–14, OCLC 47758413, archived from the original (PDF) on 12 October 2012, retrieved 1 September 2012

- Stirner, Max. The Ego and Its Own, p. 248

- Moggach, Douglas. The New Hegelians. Cambridge University Press, 2006 p. 194

- For Ourselves, "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 28 December 2008. Retrieved 17 November 2008.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) The Right to Be Greedy: Theses On The Practical Necessity Of Demanding Everything, 1974.

- "[[Alfredo M. Bonanno]]. The Theory of the Individual: Stirner's Savage Thought". Archived from the original on 15 March 2012. Retrieved 3 October 2011.

- Wolfi Landstreicher. "Egoism vs. Modernity: Welsh's Dialectical Stirner"

- Emma Goldman, Anarchism and Other Essays, p. 50.

- "The Anarchist Encyclopedia: A Gallery of Saints & Sinners" Recollection Used Books Archived 11 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine 23 August 2010

- Trautmann, The Voice of Terror, pp. 18–19.

- Kunina and Pospelova with Kalennikova (eds.), Marx Engels Collected Works, vol. 45, pg. 508, footnote 466.

- Natalia Kalennikova, "Johann Joseph Most," in Marx Engels Collected Works, vol. 45, pg. 545.

- Goodway, David. Anarchist Seeds Beneath the Snow. Liverpool University Press, 2006, p. 99.

- Leopold, David (4 August 2006). "Max Stirner". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- The Encyclopedia Americana: A Library of Universal Knowledge. Encyclopedia Corporation. p. 176.

- Miller, David. "Anarchism." 1987. The Blackwell Encyclopaedia of Political Thought. Blackwell Publishing. p. 11.

- "What my might reaches is my property; and let me claim as property everything I feel myself strong enough to attain, and let me extend my actual property as fas as I entitle, that is, empower myself to take..." In Ossar, Michael. 1980. Anarchism in the Dramas of Ernst Toller. SUNY Press. p. 27.

- Nyberg, Svein Olav. "max stirner". Non Serviam. Retrieved 4 December 2008.

- Carlson, Andrew (1972). "Philosophical Egoism: German Antecedents". Anarchism in Germany. Metuchen: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 0-8108-0484-0. Retrieved 4 December 2008.

- "New England Anarchism in Germany" by Thomas A. Riley Archived 8 March 2012 at WebCite

- Karl Heinrich Ulrichs had begun a journal called Prometheus in 1870, but only one issue was published. Kennedy, Hubert, Karl Heinrich Ulrichs: First Theorist of Homosexuality, In: 'Science and Homosexualities', ed. Vernon Rosario (pp. 26–45). New York: Routledge, 1997.

- "Among the egoist papers that Tucker followed were the German Der Eigene, edited by Adolf Brand... "Benjamin Tucker and Liberty: A Bibliographical Essay" by Wendy McElroy

- Constantin Parvulescu. "Der Einzige" and the making of the radical Left in the early post-World War I Germany. University of Minnesota. 2006]

- "...the dadaist objections to Hiller's activism werethemselves present in expressionism as demonstrated by the seminal roles played by the philosophies of Otto Gross and Salomo Friedlaender". Seth Taylor. Left-wing Nietzscheans: the politics of German expressionism, 1910–1920. Walter De Gruyter Inc. 1990

- The New York Times, 20 July 1934, quoted in "Erich Mühsam (1868–1934)" in MAN! A Journal of the Anarchist Ideal and Movement. Vol. 2, No. 8 (August 1934).

-

- Vallance, Margaret (July 1973). "Rudolf Rocker – a biographical sketch". Journal of Contemporary History. London/Beverly Hills: Sage Publications. 8 (3): 75–95. doi:10.1177/002200947300800304. ISSN 0022-0094. OCLC 49976309.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) Vallance 1973, pp. 77–78

- Vallance 1973, pp. 80–81

- Vallance 1973, p. 80

- Vallance 1973, pp. 81–85 and Rübner 2007

- Vallance 1973, pp. 86–88

- Vallance 1973, pp. 82–83, 88–89

- Vallance 1973, pp. 90–91

- Vallance 1973, p. 91

- Rothfels 1951, p. 839

- Vallance 1973, p. 93

- Vallance 1973, pp. 94–95

- On the history of GWR and other libertarian periodicals in Germany cf. Bernd Drücke: Zwischen Schreibtisch und Straßenschlacht? Anarchismus und libertäre Presse in Ost- und Westdeutschland, doctoral thesis, Verlag Klemm & Oelschläger, Ulm 1998, p. 165 ff. ISBN 3-932577-05-1

- Arbeiterinnen is the female version of the male Arbeiter, both mean workers in English

- The International Workers Association is called Internationale Arbeiter-Assoziation in German, hence the abbreviation IAA

- Föderation Deutschsprachiger AnarchistInnen

Bibliography

- Bartsch, Günter (1972). Anarchismus in Deutschland: 1945–1965 (in German). Hanover: Fackelträger-Verlag. ISBN 3-7716-1331-0.

- Bartsch, Günter (1973). Anarchismus in Deutschland: 1965–1973 (in German). Hanover: Fackelträger-Verlag. ISBN 3-7716-1351-5.

- Bartsch, Günter (1978). "Entwicklung und Organisationen des deutschen Anarchismus von 1945 bis zur Gegenwart: Ein Überblick". In Funke, Manfred (ed.). Extremismus im demokratischen Rechtsstaat: ausgewählte Texte und Materialien zur aktuellen Diskussion. Schriftenreihe der Bundeszentrale für Politische Bildung. 122. London: Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung. pp. 147–163. ISBN 3-921352-23-1.

- Bock, Hans-Manfred (1993) [1967]. Syndikalismus und Linkskommunismus von 1918 bis 1923: Ein Beitrag zur Sozial- und Ideengeschichte der frühen Weimarer Republik (in German). Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft. ISBN 3-534-12005-1.

- Bock, Hans-Manfred (1973). "Bibliographischer Versuch zur Geschichte des Anarchismus und Anarcho-Syndikalismus in Deutschland". In Funke, Manfred (ed.). Über Karl Korsch. Jahrbuch der Arbeiterbewegung (in German). 1. Frankfurt am Main: Fischer-Taschenbuch-Verlag. pp. 294–334. ISBN 3-436-01793-0.

- Bock, Hans-Manfred (1976). Geschichte des "linken Radikalismus" in Deutschland: ein Versuch (in German). Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp. ISBN 3-518-00645-2.

- Botz, Gerhard; Brandstetter, Gerfried; Pollak, Michael (1977). Im Schatten der Arbeiterbewegung: zur Geschichte des Anarchismus in Österreich und Deutschland (in German). Vienna: Europaverlag. ISBN 3-203-50628-9.

- Carlson, Andrew R. (1972). Anarchism in Germany: the early movement. Metuchen, NJ: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 0-8108-0484-0.

- Carlson, Andrew (1982). "Anarchism and individual terror in the German Empire, 1870–90". In Mommsen, Wolfgang J (ed.). Social protest, violence and terror in nineteenth- and twentieth-century Europe. London: Macmillan. pp. 175–200. ISBN 0-312-73471-9.

- Cohn, Jesse (2009). "Anarchism, Germany". In Ness, Immanuel (ed.). The International Encyclopedia of Revolution and Protest. Malden, Ma: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4051-8464-9.

- Degen, Hans Jürgen (2002). Anarchismus in Deutschland 1945–1960: die Föderation Freiheitlicher Sozialisten (in German). Ulm: Klemm und Oelschläger. ISBN 3-932577-37-X.

- Drücke, Bernd (1998). Zwischen Schreibtisch und Straßenschlacht? Anarchismus und libertäre Presse in Ost- und Westdeutschland (in German). Ulm: Klemm & Oelschläger. ISBN 3-932577-05-1.

- Fähnders, Walter (1987). Anarchismus und Literatur: Ein vergessenes Kapitel deutscher Literaturgeschichte zwischen 1890 und 1910 (in German). Stuttgart: Metzler. ISBN 3-476-00622-0.

- Gabriel, Elun (2003). Anarchism and the political culture of imperial Germany, 1870–1914 (PhD thesis). University of California, Davis. OCLC 53980701.

- Gabriel, Elun (2010). "The Left Liberal Critique of Anarchism in Imperial Germany". German Studies Review. Tempe: Arizona State University. 33 (2): 331–350. ISSN 0149-7952.

- Gabriel, Elun (2011). "Anarchism's Appeal to German Workers, 1878–1914". Journal for the Study of Radicalism. East Lansing: Michigan State University Press. 5 (1): 33–65. doi:10.1353/jsr.2011.0000. ISSN 1930-1189.

- Graf, Andreas G. (2001). Anarchisten gegen Hitler : Anarchisten, Anarcho-Syndikalisten, Rätekommunisten in Widerstand und Exil (in German). Berlin: Lukas-Verlag.

- Jenrich, Holger (1988). Anarchistische Presse in Deutschland 1945 – 1985 (in German). Grafenau-Döffingen: Trotzdem-Verlag. ISBN 3-922209-75-0.

- Kley, Martin Michael (2008). All work and no play?: Labor, literature, and industrial modernity on the Weimar left (PhD thesis). University of Texas, Austin. OCLC 243797442.

- Linse, Ulrich (1969a). Organisierter Anarchismus im Deutschen Kaiserreich von 1871 (in German). Berlin: Duncker Humblot.

- Linse, Ulrich (1969b). "Der deutsche Anarchismus 1870–1918". Geschichte in Wissenschaft und Unterricht (in German). Stuttgart: Friedrich Verlag (20): 513–519. ISSN 0016-9056. OCLC 473322316.

- Linse, Ulrich (1989). "Die "Schwarzen Scharen": Eine antifaschistische Kampforganisation deutscher Anarchisten". Archiv für die Geschichte des Widerstandes und der Arbeit (in German). Fernwald: Germinal Verlag. 12: 47–67. ISBN 978-3-88663-412-5.

- Neubert, Ehrhart (1998). Geschichte der Opposition in der DDR: 1949–1989 (in German). Berlin: Links-Verlag. ISBN 3-86153-163-1.

- Riley, Thomas A. (1945). "New England Anarchism in Germany". New England Quarterly. Cambridge, Ma: MIT Press. 18 (1): 25–38. doi:10.2307/361389. ISSN 0028-4866. JSTOR 361389. S2CID 147274338.

- Schmück, Jochen (1992). "Der deutschsprachige Anarchismus und seine Presse". Archiv für die Geschichte des Widerstandes und der Arbeit (in German). Fernwald: Germinal Verlag. 12: 177–190. ISBN 978-3-88663-412-5.

- Vogel, Angela (1977). Der deutsche Anarcho-Syndikalismus: Genese und Theorie einer vergessenen Bewegung (in German). Berlin: Karin Kramer Verlag. ISBN 3-87956-070-6.

- Woodcock, George (1962). Anarchism: a history of libertarian ideas and movements. New York: New American Library.