Anarchist archives

Anarchist archives preserve records from the international anarchist movement in personal and institutional collections around the world.[1] This primary source documentation is made available for researchers to learn directly from movement anarchists, both their ideas and lives.[1]

Anarchism, an anti-authoritarian political philosophy of self-governed societies without unjust hierarchies, has spread chiefly through published propaganda literature: pamphlets, books, and newspapers. As a result, American and European anarchists have a history of collecting the movement's written work and anarchist libraries naturally followed.[2]

Independent collections

.jpg)

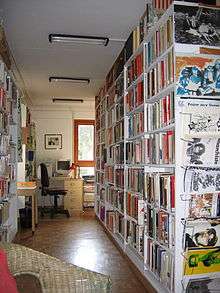

Small, independent archival collections include the Kate Sharpley Library and the Boston Anarchist Archives Project.[3] The Kate Sharpley Library (KSL) is maintained by a group[4] and has a special focus on Spanish anarchist materials, based on donations from those who settled in England after the Spanish Civil War.[5] The Kate Sharpley collection extends to class conflict history, as well. The Alternative Gallery (or A Gallery) in Greece has a wider focus, of which anarchism is one part.[4] Jerry Kaplan's Anarchist Archives Project (AAP) is a 12,000-item archive of global anarchism held privately in Cambridge, Massachusetts and developed from 1982 through at least the late 1990s.[6] It has a special focus on Italian-American anarchism, based on individual donations, and is strongest in late-20th century American and Canadian anarchism.[5] Beyond its anarchist collections, it includes some situationist and council communist items,[4] and has exchanged items with the Kate Sharpley Library, which are each located in a private residence.[5]

These independent archives tend to have a narrower focus than their institutional counterparts, whose other collections are either unrelated or part of larger leftist or labor categories. Smaller collections also benefit from personal connections to the movement, receiving leaflets and other ephemera that institutions can miss.[4]

Institutional collections

Major institutional collections include the University of Michigan's Labadie Collection and the Netherlands' International Institute of Social History (IISG). The Labadie Collection started as an independent archive,[4] and the Dutch IISG is the foremost repository of anarchist documents in the world.[7][8] Other collections in institutions not wholly dedicated to anarchism include the Joseph Ishill collection in Houghton Library at Harvard University. These institutions tend to have larger acquisition budgets than the small, independent collections, as well as more advanced machinery and more accessible space and staffing. Older, rare documents are most likely housed in institutions, who often arrange to receive an activist's personal papers and can afford to maintain them.[4]

Other collections

Other notable anarchist collections include Das Anarchiv (Basel), Anarchistisches Dokumentationszentrum (Wetzlar, Germany), Centro Studi Libertari "Giuseppe Pinelli" (Milan), Centre d'Etudes et de Documentation Librairie (Lyon), Fundación Salvador Seguí (Madrid), and the Centre International de Recherches sur l'Anarchisme (Lausanne, Switzerland, Marseille, France)[5] and Japan.[9]

References

- Kaplan 1997, p. 3.

- Moran 2014.

- Kaplan 1997, pp. 3, 6.

- Kaplan 1997, p. 6.

- Kaplan 1997, p. 8.

- Kaplan 1997, pp. 3, 8.

- Avrich, Paul (1979). "Review of The American as Anarchist: Reflections on Indigenous Radicalism". The American Historical Review. 84 (5): 1467–1468. doi:10.2307/1861661. ISSN 0002-8762. JSTOR 1861661.

- Suriano, Juan (2010). Paradoxes of Utopia: Anarchist Culture and Politics in Buenos Aires, 1890-1910. AK Press. p. 252. ISBN 978-1-84935-044-0.

- "CIRA – Nippon: A short introduction". LibCom. Retrieved April 2, 2019.

Bibliography

- Kaplan, Jerry (Spring 1997). "Preserving Our Past: The Anarchist Collections". Perspectives on Anarchist Theory. 1 (1): 3, 6, 8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Moran, Jessica (2014). "To Spread the Revolution: Anarchist Archives and Libraries". In Morrone, Melissa (ed.). Informed Agitation: Library and Information Skills in Social Justice Movements and Beyond. Sacramento, California: Library Juice Press. pp. 173–184. ISBN 978-1-936117-87-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Everett, Martyn (October 1991). "Notes on Sources: A Preliminary Survey of Material Relating to the History of the Anarchist Movement in Britain". Labour History Review. 56 (2): 41–50. doi:10.3828/lhr.56.2.41. ISSN 0961-5652.

- Goodway, David (2008). "The Kate Sharpley Library". Anarchist Studies. 16 (1): 91–96. ISSN 0967-3393. ProQuest 211031548.

- Hoyt, Andrew (October 2012). "The International Anarchist Archives: A Report on Conditions and a Proposal for Action". Theory in Action. 5 (4): 30–46. doi:10.3798/tia.1937-0237.12031. ISSN 1937-0237 – via Questia.

- Kinna, Ruth, ed. (2012). "Archives, Libraries and Treasure Troves". The Continuum Companion to Anarchism. Continuum Companions. Bloomsbury Academic. pp. 265–374. ISBN 978-1-4411-7212-9.

- Pezzica, Lorenzo (Fall 2003). Translated by Engel-Di Mauro, Salvatore. "Libertarian Archives in South America". Perspectives on Anarchist Theory. 7 (2): 18.

- "Musée: au CIRA, tout sur les anars mais point de foutoir". La Libre Belgique (in French). Agence France-Presse. July 6, 2013. Retrieved March 31, 2019.

- Stowasser, Horst (October 2007). "Die 'Mutter der Archive': 50 Jahre CIRA - Internationales Treffen in Lausanne". Graswurzelrevolution (in German) (322).

- West, Jessamyn (June 2007). "An Interview with Three Members of the Kate Sharpley Library". Serials Review. 33 (2): 129–131. doi:10.1016/j.serrev.2007.02.003. ISSN 0098-7913.

External links

![]()