Substance use disorder

Substance use disorder (SUD) is the persistent use of drugs (including alcohol) despite substantial harm and adverse consequences.[1][2] Substance use disorders are characterized by an array of mental/emotional, physical, and behavioral problems such as chronic guilt; an inability to reduce or stop consuming the substance(s) despite repeated attempts; driving while intoxicated; and physiological withdrawal symptoms.[1] Drug classes that are involved in SUD include: alcohol; caffeine; cannabis; phencyclidine and other hallucinogens, such as arylcyclohexylamines; inhalants; opioids; sedatives, hypnotics, or anxiolytics; stimulants; tobacco; and other or unknown substances.[1][3]

| Substance use disorder | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Drug use disorder |

| |

| Specialty | Psychiatry, clinical psychology |

In the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5th edition (2013), also known as DSM-5, the DSM-IV diagnoses of substance abuse and substance dependence were merged into the category of substance use disorders.[4][5] The severity of substance use disorders can vary widely; in the DSM-5 diagnosis of a SUD, the severity of an individual's SUD is qualified as mild, moderate, or severe on the basis of how many of the 11 diagnostic criteria are met. The International Classification of Diseases 11th revision (ICD-11) divides substance use disorders into two categories: (1) harmful pattern of substance use; and (2) substance dependence.[6]

In 2017 globally 271 million people (5.5% of adults) were estimated to have used one or more illicit drugs.[7] Of these 35 million had a substance use disorder.[7] An additional 237 million men and 46 million women have alcohol use disorder as of 2016.[8] In 2017 substance use disorders from illicit substances directly resulted in 585,000 deaths.[7] Direct deaths from drug use, other than alcohol, have increased over 60 percent from 2000 to 2015.[9] Alcohol use resulted in an additional 3 million deaths in 2016.[8]

Causes

There are many known risk factors associated with an increased chance of developing a substance use disorder. Children born to parents with SUDs have roughly a two-fold increased risk in developing a SUD compared to children born to parents without any SUDs.[10] Taking highly addictive drugs, and those who develop SUDs in their teens are more likely to have continued symptoms into adulthood.[10] Other common risk factors are being male, being under 25, having other mental health problems, and lack of familial support and supervision.[10] Psychological risk factors include high impulsivity, sensation seeking, neuroticism and openness to experience in combination with low conscientiousness.[11][12]

Diagnosis

| Addiction and dependence glossary[13][14][15][16] | |

|---|---|

| |

Individuals whose drug or alcohol use cause significant impairment or distress may have a substance use disorder (SUD).[1] Diagnosis usually involves an in-depth examination, typically by psychiatrist, psychologist, or drug and alcohol counselor.[17] The most commonly used guidelines are published in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5).[17] There are 11 diagnostic criteria which can be broadly categorized into issues arising from substance use related to loss of control, strain to one's interpersonal life, hazardous use, and pharmacologic effects.[1]

DSM-5 guidelines for the diagnosis of a substance use disorder require that the individual have significant impairment or distress from their pattern of drug use, and at least two of the symptoms listed below in a given year.[1]

- Using more of a substance than planned, or using a substance for a longer interval than desired

- Inability to cut down despite desire to do so

- Spending substantial amount of the day obtaining, using, or recovering from substance use

- Cravings or intense urges to use

- Repeated usage causes or contributes to an inability to meet important social, or professional obligations

- Persistent usage despite user's knowledge that it is causing frequent problems at work, school, or home

- Giving up or cutting back on important social, professional, or leisure activities because of use

- Using in physically hazardous situations, or usage causing physical or mental harm

- Persistent use despite the user's awareness that the substance is causing or at least worsening a physical or mental problem

- Tolerance: needing to use increasing amounts of a substance to obtain its desired effects

- Withdrawal: characteristic group of physical effects or symptoms that emerge as amount of substance in the body decreases

There are additional qualifiers and exceptions outlined in the DSM. For instance, if an individual is taking opiates as prescribed, they may experience physiologic effects of tolerance and withdrawal, but this would not cause an individual to meet criteria for a SUD without additional symptoms also being present.[1] A physician trained to evaluate and treat substance use disorders will take these nuances into account during a diagnostic evaluation.

Severity

Substance use disorders can range widely in severity, and there are numerous methods to monitor and qualify the severity of an individual's SUD. The DSM-5 includes specifiers for severity of a SUD.[1] Individuals who meet only 2 or 3 criteria are often deemed to have mild SUD.[1] Substance users who meet 4 or 5 criteria may have their SUD described as moderate, and persons meeting 6 or more criteria as severe.[1] In the DSM-5, the term drug addiction is synonymous with severe substance use disorder.[16][18] The quantity of criteria met offer a rough gauge on the severity of illness, but licensed professionals will also take into account a more holistic view when assessing severity which includes specific consequences and behavioral patterns related to an individual's substance use.[1] They will also typically follow frequency of use over time, and assess for substance-specific consequences, such as the occurrence of blackouts, or arrests for driving under the influence of alcohol, when evaluating someone for an alcohol use disorder.[1] There are additional qualifiers for stages of remission that are based on the amount of time an individual with a diagnosis of a SUD has not met any of the 11 criteria except craving.[1] Some medical systems refer to an Addiction Severity Index to assess the severity of problems related to substance use.[19] The index assesses potential problems in seven categories: medical, employment/support, alcohol, other drug use, legal, family/social, and psychiatric.[20]

Screening tools

There are several different screening tools that have been validated for use with adolescents, such as the CRAFFT, and with adults, such as CAGE. Laboratory tests to detect alcohol and other drugs in urine and blood may be useful during the assessment process to confirm a diagnosis, to establish a baseline, and later, to monitor progress.[21] However, since these tests measure recent substance use rather than chronic use or dependence, they are not recommended as screening tools.[21]

Mechanisms

Management

Detoxification

Depending on the severity of use, and the given substance, early treatment of acute withdrawal may include medical detoxification. Of note, acute withdrawal from heavy alcohol use should be done under medical supervision to prevent a potentially deadly withdrawal syndrome known as delirium tremens. See also Alcohol detoxification.

Therapy

Therapists often classify people with chemical dependencies as either interested or not interested in changing. About 11% of Americans with substance use disorder seek treatment, and 40–60% of those people relapse within a year.[22] Treatments usually involve planning for specific ways to avoid the addictive stimulus, and therapeutic interventions intended to help a client learn healthier ways to find satisfaction. Clinical leaders in recent years have attempted to tailor intervention approaches to specific influences that affect addictive behavior, using therapeutic interviews in an effort to discover factors that led a person to embrace unhealthy, addictive sources of pleasure or relief from pain.

| Treatments | ||

|---|---|---|

| Behavioral pattern | Intervention | Goals |

| Low self-esteem, anxiety, verbal hostility | Relationship therapy, client centered approach | Increase self-esteem, reduce hostility and anxiety |

| Defective personal constructs, ignorance of interpersonal means | Cognitive restructuring including directive and group therapies | Insight |

| Focal anxiety such as fear of crowds | Desensitization | Change response to same cue |

| Undesirable behaviors, lacking appropriate behaviors | Aversive conditioning, operant conditioning, counter conditioning | Eliminate or replace behavior |

| Lack of information | Provide information | Have client act on information |

| Difficult social circumstances | Organizational intervention, environmental manipulation, family counseling | Remove cause of social difficulty |

| Poor social performance, rigid interpersonal behavior | Sensitivity training, communication training, group therapy | Increase interpersonal repertoire, desensitization to group functioning |

| Grossly bizarre behavior | Medical referral | Protect from society, prepare for further treatment |

| Adapted from: Essentials of Clinical Dependency Counseling, Aspen Publishers | ||

From the applied behavior analysis literature and the behavioral psychology literature, several evidence-based intervention programs have emerged, such as behavioral marital therapy, community reinforcement approach, cue exposure therapy, and contingency management strategies.[23][24] In addition, the same author suggests that social skills training adjunctive to inpatient treatment of alcohol dependence is probably efficacious.

Medication

Medication-assisted treatment (MAT) refers to the combination of behavioral interventions and medications to treat substance use disorders.[25] Certain medications can be useful in treating severe substance use disorders. In the United States five medications are approved to treat alcohol and opioid use disorders.[26] There are no approved medications for cocaine, methamphetamine, or other substance use disorders as of 2002.[26]

Medications, such as methadone and disulfiram, can be used as part of broader treatment plans to help a patient function comfortably without illicit opioids or alcohol.[27] Medications can be used in treatment to lessen withdrawal symptoms. Evidence has demonstrated the efficacy of MAT at reducing illicit drug use and overdose deaths, improving retention in treatment, and reducing HIV transmission.[28][29][30]

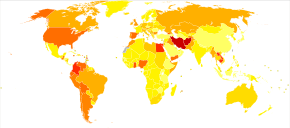

Epidemiology

Rates of substance use disorders vary by nation and by substance, but the overall prevalence is high.[31] On a global level, men are affected at a much higher rate than women.[31] Younger individuals are also more likely to be affected than older adults.[31]

United States

In 2017, roughly 7% of Americans aged 12 or older had a SUD in the past year.[32] Rates of alcohol use disorder in the past year were just over 5%. Approximately 3% of people aged 12 or older had an illicit drug use disorder.[32] The highest rates of illicit drug use disorder were among those aged 18 to 25 years old, at roughly 7%.[32][31]

There were over 72,000 deaths from drug overdose in the United States in 2017,[33] which is a threefold increase from 2002.[33] However the CDC calculates alcohol overdose deaths separately; thus, this 72,000 number does not include the 2,366 alcohol overdose deaths in 2017.[34] Overdose fatalities from synthetic opioids, which typically involve fentanyl, have risen sharply in the past several years to contribute to nearly 30,000 deaths per year.[33] Death rates from synthetic opioids like fentanyl have increased 22-fold in the period from 2002 to 2017.[33] Heroin and other natural and semi-synthetic opioids combined to contribute to roughly 31,000 overdose fatalities.[33] Cocaine contributed to roughly 15,000 overdose deaths, while methamphetamine and benzodiazepines each contributed to roughly 11,000 deaths.[33] Of note, the mortality from each individual drug listed above cannot be summed because many of these deaths involved combinations of drugs, such as overdosing on a combination of cocaine and an opioid.[33]

Deaths from alcohol consumption account for the loss of over 88,000 lives per year.[35] Tobacco remains the leading cause of preventable death, responsible for greater than 480,000 deaths in the United States each year.[36] These harms are significant financially with total costs of more than $420 billion annually and more than $120 billion in healthcare.[37]

Canada

According to Statistics Canada (2018), approximately one in five Canadians aged 15 years and older experience a substance use disorder in their lifetime.[38] In Ontario specifically, the disease burden of mental illness and addiction is 1.5 times higher than all cancers together and over 7 times that of all infectious diseases.[39] Across the country, the ethnic group that is statistically the most impacted by substance use disorders compared to the general population are the Indigenous peoples of Canada. In a 2019 Canadian study, it was found that Indigenous participants experienced greater substance-related problems than non-Indigenous participants.[40]

Statistics Canada's Canadian Community Health Survey (2012) shows that alcohol was the most common substance for which Canadians met the criteria for abuse or dependence.[38] Surveys on Indigenous people in British Columbia show that around 75% of residents on reserve feel alcohol use is a problem in their community and 25% report they have a problem with alcohol use themselves. However, only 66% of First Nations adults living on reserve drink alcohol compared to 76% of the general population.[41] Further, in an Ontario study on mental health and substance use among Indigenous people, 19% reported the use of cocaine and opiates, higher than the 13% of Canadians in the general population that reported using opioids.[42][43]

Australia

Historical and ongoing colonial practices continue to impact the health of Indigenous Australians, with Indigenous populations being more susceptible to substance use and related harms.[44] For example, alcohol and tobacco are the predominant substances used in Australia.[45] Although tobacco smoking is declining in Australia, it remains disproportionately high in Indigenous Australians with 45% aged 18 and over being smokers, compared to 16% among non-Indigenous Australians in 2014–2015.[46] As for alcohol, while proportionately more Indigenous people refrain from drinking than non-Indigenous people, Indigenous people who do consume alcohol are more likely to do so at high-risk levels.[47] About 19% of Indigenous Australians qualified for risky alcohol consumption (defined as 11 or more standard drinks at least once a month), which is 2.8 times the rate that their non-Indigenous counterparts consumed the same level of alcohol.[46]

However, while alcohol and tobacco usage are declining, use of other substances, such as cannabis and opiates, is increasing in Australia.[44] Cannabis is the most widely used illicit drug in Australia, with cannabis usage being 1.9 times higher than non-Indigenous Australians.[46] Prescription opioids have seen the greatest increase in usage in Australia, although use is still lower that in the US.[48] In 2016, Indigenous persons were 2.3 times more likely to misuse pharmaceutical drugs than non-Indigenous people.[46]

References

- Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association. 2013. ISBN 978-0-89042-554-1. OCLC 830807378.

- "NAMI Comments on the APA's Draft Revision of the DSM-V Substance Use Disorders" (PDF). National Alliance on Mental Illness. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 January 2015. Retrieved 2 November 2013.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (June 2016). Substance Use Disorders. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US).

- Guha M (11 March 2014). "Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5 (5th edition)". Reference Reviews. 28 (3). doi:10.1108/RR-10-2013-0256. ISSN 0950-4125.

- Hasin DS, O'Brien CP, Auriacombe M, Borges G, Bucholz K, Budney A, et al. (August 2013). "DSM-5 criteria for substance use disorders: recommendations and rationale". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 170 (8): 834–51. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.12060782. PMC 3767415. PMID 23903334.

- World Health Organization, ICD-11 for Mortality and Morbidity Statistics (ICD-11 MMS), 2018 version for preparing implementation, rev. April 2019

- "World Drug Report 2019: 35 million people worldwide suffer from drug use disorders while only 1 in 7 people receive treatment". www.unodc.org. Retrieved 25 November 2019.

- Global status report on alcohol and health 2018 (PDF). WHO. 2018. p. xvi. Retrieved 3 May 2020.

- "Prelaunch". www.unodc.org. Retrieved 14 December 2018.

- Ferri, Fred (2019). Ferri's Clinical Advisor. Elsevier.

- Belcher AM, Volkow ND, Moeller FG, Ferré S (April 2014). "Personality traits and vulnerability or resilience to substance use disorders". Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 18 (4): 211–7. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2014.01.010. PMC 3972619. PMID 24612993.

- Fehrman E, Egan V, Gorban AN, Levesley J, Mirkes EM, Muhammad AK (2019). Personality Traits and Drug Consumption. A Story Told by Data. Springer, Cham. arXiv:2001.06520. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-10442-9. ISBN 978-3-030-10441-2.

- Nestler EJ (December 2013). "Cellular basis of memory for addiction". Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience. 15 (4): 431–443. PMC 3898681. PMID 24459410.

Despite the importance of numerous psychosocial factors, at its core, drug addiction involves a biological process: the ability of repeated exposure to a drug of abuse to induce changes in a vulnerable brain that drive the compulsive seeking and taking of drugs, and loss of control over drug use, that define a state of addiction. ... A large body of literature has demonstrated that such ΔFosB induction in D1-type [nucleus accumbens] neurons increases an animal's sensitivity to drug as well as natural rewards and promotes drug self-administration, presumably through a process of positive reinforcement ... Another ΔFosB target is cFos: as ΔFosB accumulates with repeated drug exposure it represses c-Fos and contributes to the molecular switch whereby ΔFosB is selectively induced in the chronic drug-treated state.41 ... Moreover, there is increasing evidence that, despite a range of genetic risks for addiction across the population, exposure to sufficiently high doses of a drug for long periods of time can transform someone who has relatively lower genetic loading into an addict.

- Malenka RC, Nestler EJ, Hyman SE (2009). "Chapter 15: Reinforcement and Addictive Disorders". In Sydor A, Brown RY (eds.). Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. pp. 364–375. ISBN 9780071481274.

- "Glossary of Terms". Mount Sinai School of Medicine. Department of Neuroscience. Retrieved 9 February 2015.

- Volkow ND, Koob GF, McLellan AT (January 2016). "Neurobiologic Advances from the Brain Disease Model of Addiction". New England Journal of Medicine. 374 (4): 363–371. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1511480. PMC 6135257. PMID 26816013.

Substance-use disorder: A diagnostic term in the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) referring to recurrent use of alcohol or other drugs that causes clinically and functionally significant impairment, such as health problems, disability, and failure to meet major responsibilities at work, school, or home. Depending on the level of severity, this disorder is classified as mild, moderate, or severe.

Addiction: A term used to indicate the most severe, chronic stage of substance-use disorder, in which there is a substantial loss of self-control, as indicated by compulsive drug taking despite the desire to stop taking the drug. In the DSM-5, the term addiction is synonymous with the classification of severe substance-use disorder. - "Drug addiction (substance use disorder) – Symptoms and causes". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 7 December 2018.

- "Facing Addiction in America: The Surgeon General's Report on Alcohol, Drugs, and Health" (PDF). Office of the Surgeon General. US Department of Health and Human Services. November 2016. pp. 35–37, 45, 63, 155, 317, 338. Retrieved 28 January 2017.

- Butler SF, Budman SH, Goldman RJ, Newman FL, Beckley KE, Trottier D. Initial Validation of a Computer-Administered Addiction Severity Index: The ASI-MV Psychology of Addictive Behaviors 2001 March

- "DARA Thailand". Retrieved 4 June 2017.

- Treatment, Center for Substance Abuse (1997). Chapter 2—Screening for Substance Use Disorders. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US).

- McLellan AT, Lewis DC, O'Brien CP, Kleber HD (October 2000). "Drug dependence, a chronic medical illness: implications for treatment, insurance, and outcomes evaluation". JAMA. 284 (13): 1689–95. doi:10.1001/jama.284.13.1689. PMID 11015800.

- O'Donohue W, Ferguson KE (2006). "Evidence-Based Practice in Psychology and Behavior Analysis". The Behavior Analyst Today. 7 (3): 335–350. doi:10.1037/h0100155. Retrieved 24 March 2008.

- Chambless DL, et al. (1998). "An update on empirically validated therapies" (PDF). Clinical Psychology. American Psychological Association. 49: 5–14. Retrieved 24 March 2008.

- Bonhomme J, Shim RS, Gooden R, Tyus D, Rust G (July 2012). "Opioid addiction and abuse in primary care practice: a comparison of methadone and buprenorphine as treatment options". Journal of the National Medical Association. 104 (7–8): 342–50. doi:10.1016/s0027-9684(15)30175-9. PMC 4039205. PMID 23092049.

- American Psychiatric Association. (2002). American Psychiatric Association practice guidelines for the treatment of psychiatric disorders. The Association. ISBN 0-89042-320-2. OCLC 48656105.

- Massachusetts. Center for Health Information and Analysis, issuing body. Access to substance use disorder treatment in Massachusetts. OCLC 911187572.

- Holt, Dr. Harry (15 July 2019). "Stigma Associated with Opioid Use Disorder and Medication Assisted Treatment". doi:10.31124/advance.8866331. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Schwartz RP, Gryczynski J, O'Grady KE, Sharfstein JM, Warren G, Olsen Y, et al. (May 2013). "Opioid agonist treatments and heroin overdose deaths in Baltimore, Maryland, 1995-2009". American Journal of Public Health. 103 (5): 917–22. doi:10.2105/ajph.2012.301049. PMC 3670653. PMID 23488511.

- Administration (US), Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services; General (US), Office of the Surgeon (November 2016). EARLY INTERVENTION, TREATMENT, AND MANAGEMENT OF SUBSTANCE USE DISORDERS. US Department of Health and Human Services.

- Galanter M, Kleber HD, Brady KT (17 December 2014). The American Psychiatric Publishing Textbook of Substance Abuse Treatment. doi:10.1176/appi.books.9781615370030. ISBN 978-1-58562-472-0.

- "Reports and Detailed Tables From the 2017 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) | CBHSQ". www.samhsa.gov. 11 September 2018. Retrieved 6 December 2018.

- Abuse, National Institute on Drug (9 August 2018). "Overdose Death Rates". www.drugabuse.gov. Retrieved 6 December 2018.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. Substance-induced cause, 2017, percent total, with standard error from the Underlying Cause of Death 1999-2018 CDC WONDER Online Database. Accessed at http://wonder.cdc.gov/ucd-icd10.html on 18 March 2020 at 18:06 UTC.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2013). "Alcohol and Public Health: Alcohol-Related Disease Impact (ARDI)". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Retrieved 6 December 2018.

- "Smoking and Tobacco Use; Fact Sheet; Fast Facts". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 9 May 2018. Retrieved 6 December 2018.

- Sacks JJ, Gonzales KR, Bouchery EE, Tomedi LE, Brewer RD (November 2015). "2010 National and State Costs of Excessive Alcohol Consumption". American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 49 (5): e73–e79. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2015.05.031. PMID 26477807.

- Canada, Health (5 September 2018). "Strengthening Canada's Approach to Substance Use Issues". gcnws. Retrieved 1 November 2019.

- "Opening Eyes, Opening Minds: The Ontario Burden of Mental Illness and Addictions Report". Public Health Ontario. Retrieved 1 November 2019.

- Bingham B, Moniruzzaman A, Patterson M, Distasio J, Sareen J, O'Neil J, Somers JM (April 2019). "Indigenous and non-Indigenous people experiencing homelessness and mental illness in two Canadian cities: A retrospective analysis and implications for culturally informed action". BMJ Open. 9 (4): e024748. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2018-024748. PMC 6500294. PMID 30962229.

- "Aboriginal Mental Health: The statistical reality | Here to Help". www.heretohelp.bc.ca. Retrieved 1 November 2019.

- "Prescription Opioids (Canadian Drug Summary) | Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction". www.ccsa.ca. Retrieved 1 November 2019.

- Firestone M, Smylie J, Maracle S, McKnight C, Spiller M, O'Campo P (June 2015). "Mental health and substance use in an urban First Nations population in Hamilton, Ontario". Canadian Journal of Public Health. 106 (6): e375-81. doi:10.17269/CJPH.106.4923. JSTOR 90005913. PMC 6972211. PMID 26680428.

- Berry SL, Crowe TP (January 2009). "A review of engagement of Indigenous Australians within mental health and substance abuse services". Australian e-Journal for the Advancement of Mental Health. 8 (1): 16–27. doi:10.5172/jamh.8.1.16. ISSN 1446-7984.

- Haber PS, Day CA (2014). "Overview of substance use and treatment from Australia". Substance Abuse. 35 (3): 304–8. doi:10.1080/08897077.2014.924466. PMID 24853496.

- "Alcohol, tobacco & other drugs in Australia, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people". Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Retrieved 24 November 2019.

- Sanson-Fisher RW, Campbell EM, Perkins JJ, Blunden SV, Davis BB (May 2006). "Indigenous health research: a critical review of outputs over time". Medical Journal of Australia. 184 (10): 502–505. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.2006.tb00343.x. ISSN 0025-729X.

- Leong M, Murnion B, Haber PS (October 2009). "Examination of opioid prescribing in Australia from 1992 to 2007". Internal Medicine Journal. 39 (10): 676–81. doi:10.1111/j.1445-5994.2009.01982.x. PMID 19460051.

Further reading

- Skinner WW, O'Grady CP, Bartha C, Parker C (2010). Concurrent substance use and mental health disorders : an information guide (PDF). Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH). ISBN 978-1-77052-604-4.

- Best Practices: Concurrent Mental Health and Substance Use Disorders (PDF). ISBN 0-662-31388-7.