Metkefamide

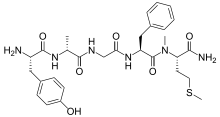

Metkefamide (INN; LY-127,623), or metkephamid acetate (USAN), but most frequently referred to simply as metkephamid, is a synthetic opioid pentapeptide and derivative of [Met]enkephalin with the amino acid sequence Tyr-D-Ala-Gly-Phe-(N-Me)-Met-NH2.[4] It behaves as a potent agonist of the δ- and μ-opioid receptors with roughly equipotent affinity,[5][6] and also has similarly high affinity as well as subtype-selectivity for the κ3-opioid receptor.[7][8]

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| ATC code |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 30-35%[1] |

| Protein binding | 44-49%[2] |

| Metabolism | Hepatic[1] |

| Elimination half-life | ~60 minutes[3] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number |

|

| PubChem CID | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C29H40N6O6S |

| Molar mass | 600.74 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

Despite its peptidic nature, upon systemic administration, metkefamide rapidly penetrates the blood-brain-barrier and disperses into the central nervous system where it produces potent, centrally-mediated analgesic effects,[9] of which have been shown to be dependent on activity at both the μ- and δ-opioid receptors.[6][10] In addition, on account of modifications to the N- and C-terminals, metkefamide is highly stable against proteolytic degradation relative to many other opioid peptides.[3][11] As an example, while its parent peptide, [Met]enkephalin, has an in vivo half-life of merely seconds, metkefamide has a half-life of nearly 60 minutes, and upon intramuscular administration, has been shown to provide pain relief that lasts for hours.[3]

Likely on account of its δ-opioid activity, clinical trials have found metkefamide to possess less of a tendency for producing many of the undesirable side effects usually associated with conventional opioids such as respiratory depression, tolerance, and physical dependence.[6][12] However, it has been shown to cause some additional side effects that are considered unusual for standard opioid analgesics like sensations of heaviness in the extremities and nasal congestion—though these were not considered to be particularly distressing[9]—and it has also been shown to raise the seizure threshold in animals.[13] In any case, clinical development was not further pursued after phase I clinical studies and metkefamide never reached the pharmaceutical market.[14][15][16]

See also

References

- J S Davies; Royal Soc of Chem (8 November 2000). Amino Acids, Peptides and Proteins. Royal Society of Chemistry. p. 258. ISBN 978-0-85404-227-2. Retrieved 27 April 2012.

- Oliver Kayser; Heribert Warzecha (13 June 2012). Pharmaceutical Biotechnology: Drug Discovery and Clinical Applications. John Wiley & Sons. p. 346. ISBN 978-3-527-32994-6. Retrieved 27 April 2012.

- Vincent H. L. Lee (1991). Peptide and Protein Drug Delivery. CRC Press. p. 90. ISBN 978-0-8247-7896-5. Retrieved 27 April 2012.

- Ian Morton; Judith M. Hall (1999). Concise Dictionary of Pharmacological Agents: Properties and Synonyms. Springer. p. 180. ISBN 978-0-7514-0499-9. Retrieved 27 April 2012.

- Burkhardt C, Frederickson RC, Pasternak GW (1982). "Metkephamid (Tyr-D-ala-Gly-Phe-N(Me)Met-NH2), a potent opioid peptide: receptor binding and analgesic properties". Peptides. 3 (5): 869–71. doi:10.1016/0196-9781(82)90029-8. PMID 6294639.

- Frederickson RC, Smithwick EL, Shuman R, Bemis KG (February 1981). "Metkephamid, a systemically active analog of methionine enkephalin with potent opioid alpha-receptor activity". Science. 211 (4482): 603–5. doi:10.1126/science.6256856. PMID 6256856.

- Linda M. Pullan; Jitendra Patel (1996). Neurotherapeutics: Emerging Strategies. Humana Press. p. 172. ISBN 978-0-89603-306-1. Retrieved 27 April 2012.

- Clark JA, Liu L, Price M, Hersh B, Edelson M, Pasternak GW (November 1989). "Kappa opiate receptor multiplicity: evidence for two U50,488-sensitive kappa 1 subtypes and a novel kappa 3 subtype". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 251 (2): 461–8. PMID 2553920.

- Calimlim JF, Wardell WM, Sriwatanakul K, Lasagna L, Cox C (June 1982). "Analgesic efficacy of parenteral metkephamid acetate in treatment of postoperative pain". Lancet. 1 (8286): 1374–5. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(82)92497-7. PMID 6123675.

- Hynes MD, Frederickson RC (1982). "Cross-tolerance studies distinguish morphine- and metkephamid-induced analgesia". Life Sciences. 31 (12–13): 1201–4. doi:10.1016/0024-3205(82)90342-3. PMID 6292609.

- Edith Mathiowitz; Donald E. Chickering; Claus-Michael Lehr (13 July 1999). Bioadhesive Drug Delivery Systems: Fundamentals, Novel Approaches, and Development. CRC Press. p. 323. ISBN 978-0-8247-1995-1. Retrieved 27 April 2012.

- Stanley Stein (31 August 1990). Fundamentals of Protein Biotechnology. CRC Press. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-8247-8346-4. Retrieved 27 April 2012.

- Tortella FC, Robles LE, Holaday JW, Cowan A (1983). "A selective role for delta-receptors in the regulation of opioid-induced changes in seizure threshold". Life Sciences. 33 Suppl 1: 603–6. doi:10.1016/0024-3205(83)90575-1. PMID 6319916.

- Denis M. Bailey (1 August 1987). Annual Reports in Medicinal Chemistry. Academic Press. p. 58. ISBN 978-0-12-040522-0. Retrieved 27 April 2012.

- MaryLouise Embrey; Christine R. Hartel (1 August 1999). Drug Abuse and Drug Abuse Research (1991): The Third Triennial Report to Congress from the Secretary, Department of Health and Human Services. DIANE Publishing. p. 51. ISBN 978-0-7881-8196-2. Retrieved 27 April 2012.

- Dictionary of Pharmacological Agents Volume 2. CRC Press. 1996-11-21. p. 1343. ISBN 978-0-412-46630-4. Retrieved 26 April 2012.