Insular dwarfism

Insular dwarfism, a form of phyletic dwarfism,[1] is the process and condition of large animals evolving or having a reduced body size[lower-alpha 1] when their population's range is limited to a small environment, primarily islands. This natural process is distinct from the intentional creation of dwarf breeds, called dwarfing. This process has occurred many times throughout evolutionary history, with examples including dinosaurs, like Europasaurus, and modern animals such as elephants and their relatives. This process, and other "island genetics" artifacts, can occur not only on islands, but also in other situations where an ecosystem is isolated from external resources and breeding. This can include caves, desert oases, isolated valleys and isolated mountains ("sky islands"). Insular dwarfism is one aspect of the more general "island effect" or "Foster's rule", which posits that when mainland animals colonize islands, small species tend to evolve larger bodies (island gigantism), and large species tend to evolve smaller bodies.

Possible causes

There are several proposed explanations for the mechanism which produces such dwarfism.[3][4]

One is a selective process where only smaller animals trapped on the island survive, as food periodically declines to a borderline level. The smaller animals need fewer resources and smaller territories, and so are more likely to get past the break-point where population decline allows food sources to replenish enough for the survivors to flourish. Smaller size is also advantageous from a reproductive standpoint, as it entails shorter gestation periods and generation times.[3]

In the tropics, small size should make thermoregulation easier.[3]

Among herbivores, large size confers advantages in coping with both competitors and predators, so a reduction or absence of either would facilitate dwarfing; competition appears to be the more important factor.[4]

Among carnivores, the main factor is thought to be the size and availability of prey resources, and competition is believed to be less important.[4] In tiger snakes, insular dwarfism occurs on islands where available prey is restricted to smaller sizes than are normally taken by mainland snakes. Since prey size preference in snakes is generally proportional to body size, small snakes may be better adapted to take small prey.[5]

Dwarfism vs. gigantism

The inverse process, wherein small animals breeding on isolated islands lacking the predators of large land masses may become much larger than normal, is called island gigantism. An excellent example is the dodo, the ancestors of which were normal-sized pigeons. There are also several species of giant rats, one still extant, that coexisted with both Homo floresiensis and the dwarf stegodonts on Flores.

The process of insular dwarfing can occur relatively rapidly by evolutionary standards. This is in contrast to increases in maximum body size, which are much more gradual. When normalized to generation length, the maximum rate of body mass decrease during insular dwarfing was found to be over 30 times greater than the maximum rate of body mass increase for a ten-fold change in mammals.[6] The disparity is thought to reflect the fact that pedomorphism offers a relatively easy route to evolve smaller adult body size; on the other hand, the evolution of larger maximum body size is likely to be interrupted by the emergence of a series of constraints that must be overcome by evolutionary innovations before the process can continue.[6]

Factors influencing the extent of dwarfing

For both herbivores and carnivores, island size, the degree of island isolation and the size of the ancestral continental species appear not to be of major direct importance to the degree of dwarfing.[4] However, when considering only the body masses of recent top herbivores and carnivores, and including data from both continental and island land masses, the body masses of the largest species in a land mass were found to scale to the size of the land mass, with slopes of about 0.5 log(body mass/kg) per log(land area/km2).[7] There were separate regression lines for endothermic top predators, ectothermic top predators, endothermic top herbivores and (on the basis of limited data) ectothermic top herbivores, such that food intake was 7 to 24-fold higher for top herbivores than for top predators, and about the same for endotherms and ectotherms of the same trophic level (this leads to ectotherms being 5 to 16 times heavier than corresponding endotherms).[7]

Examples

Non-avian dinosaurs

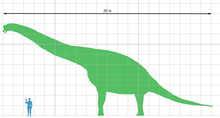

Recognition that insular dwarfism could apply to dinosaurs arose through the work of Ferenc Nopcsa, a Hungarian-born aristocrat, adventurer, scholar, and paleontologist. Nopcsa studied Transylvanian dinosaurs intensively, noticing that they were smaller than their cousins elsewhere in the world. For example, he unearthed six-meter-long sauropods, a group of dinosaurs which elsewhere commonly grew to 30 meters or more. Nopcsa deduced that the area where the remains were found was an island, Hațeg Island (now the Haţeg or Hatzeg basin in Romania) during the Mesozoic era.[8][9] Nopcsa's proposal of dinosaur dwarfism on Hațeg Island is today widely accepted after further research confirmed that the remains found are not from juveniles.[10]

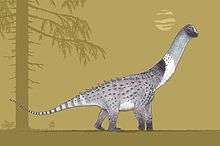

Sauropods

| Example | Species | Range | Time frame | Continental relative |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Ampelosaurus | A. atacis | Ibero-Armorican Island | Late Cretaceous / Maastrichtian |  Nemegtosaurids |

Europasaurus | E. holgeri | Lower Saxony | Late Jurassic / Middle Kimmeridgian |  Brachiosaurs |

Magyarosaurus | M. dacus | Hateg Island | Late Cretaceous / Maastrichtian |  Rapetosaurus |

Lirainosaurus[11] | L. astibiae | Ibero-Armorican Island | Late Cretaceous | |

Paludititan | P. nalatzensis | Hateg Island | Late Cretaceous / Maastrichtian |  Epachthosaurus |

Other

| Example | Species | Range | Time frame | Continental relative |

|---|---|---|---|---|

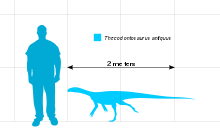

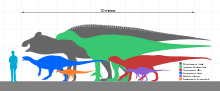

Langenberg Quarry torvosaur (blue) | Unnamed | Lower Saxony | Late Jurassic / Middle Kimmeridgian | Torvosaurus |

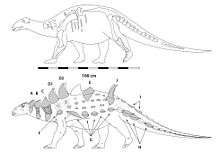

Struthiosaurus[12] | S. austriacus S. transylvanicus S. languedocensis | Ibero-Armorican, Australoalpine, and Hateg islands | Late Cretaceous | Edmontonia |

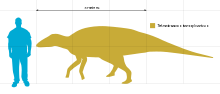

Telmatosaurus | T. transsylvanicus | Hateg Island | Late Cretaceous | Hadrosaurids |

Tethyshadros | T. insularis | Trieste province | Late Cretaceous | |

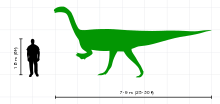

Thecodontosaurus[9] | T. antiquus | Southern England | Late Triassic / Rhaetian |  Plateosaurs |

Zalmoxes[9] (purple) | Z. robustus Z. shqiperorum | Hateg Island | Late Cretaceous |  Tenontosaurus |

In addition, the genus Balaur was initially described as a Velociraptor-sized dromaeosaurid (and in consequence a dubious example of insular dwarfism), but has been since reclassified as a secondarily flightless stem bird, closer to modern birds than Jeholornis (thus actually an example of insular gigantism).

Birds

| Example | Binomial name | Native range | Status | Continental relative | Insular / mainland length or mass ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

.jpg) Hawaiian flightless ibises | Apteribis glenos | Molokai | Extinct (Late Quaternary) |  American ibises | |

| Apteribis brevis | Maui | ||||

| Cozumel curassow[13] | Crax rubra griscomi | Cozumel | Unknown | _-_female.jpg) Great curassow | |

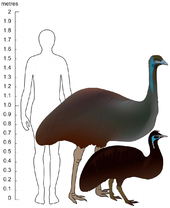

Kangaroo Island emu[14] | Dromaius novaehollandiae baudinianus | Kangaroo Island, South Australia | Extinct (c. AD 1827) |  Emu | |

King Island emu[15] (black) | Dromaius novaehollandiae minor | King Island, Tasmania | Extinct (AD 1822) | LR ≈ 0.48 [lower-alpha 2] | |

_-_Mimidae_-_bird_skin_specimen.jpeg) Cozumel thrasher[13] | Toxostoma gluttatum | Cozumel | Critically endangered |  Other thrashers |

Squamates

| Example | Binomial name | Native range | Status | Continental relative | Insular / mainland length or mass ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Madagascar dwarf chameleon | Brookesia minima | Nosy Be island, Madagascar | Endangered | .png) Madagascar leaf chameleons | |

Nosy Hara chameleon[16] | Brookesia micra | Nosy Hara island, Madagascar | Vulnerable | ||

| Roxby Island tiger snake[5] | Notechis scutatus | Roxby Island, South Australia | Unknown |  Tiger snake | |

| Dwarf Burmese python | Python bivittatus progschai | Java, Bali, Sumbawa and Sulawesi, Indonesia | Unknown | .jpg) Burmese python | LR ≈ 0.44 [lower-alpha 3] |

| Tanahjampea reticulated python[19] | Python reticulatus jampeanus | Tanahjampea, between Sulawesi and Flores | Unknown |  Reticulated python | LR ≈ 0.41, males LR ≈ 0.49, females [lower-alpha 4] |

Mammals

Pilosans

| Example | Binomial name | Native range | Status | Continental relative |

|---|---|---|---|---|

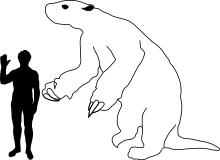

Pygmy three-toed sloth | Bradypus pygmaeus | Isla Escudo de Veraguas, Panama | Critically endangered | .jpg) Brown-throated sloth |

Acratocnus | A. antillensis A. odontrigonus A. ye | Cuba, Hispaniola and Puerto Rico | Extinct (c. 3000 BC) |  Continental ground sloths |

| Imagocnus | I. zazae | Cuba | Extinct (Early Miocene) | |

Megalocnus | M. rodens M. zile | Cuba and Hispaniola | Extinct (c. 2700 BC) | |

Neocnus | Neocnus spp. | Cuba and Hispaniola | Extinct (c. 3000 BC) |

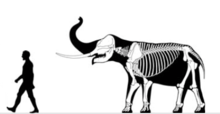

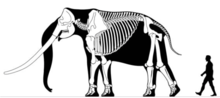

Proboscideans

| Example | Binomial name | Native range | Status | Continental relative |

|---|---|---|---|---|

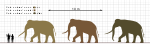

| Sulawesi dwarf elephant | Elephas celebensis | Sulawesi | Extinct (Early Pleistocene) |  Asian elephant |

Cretan dwarf mammoth | Mammuthus creticus | Crete | Extinct | Mammuthus |

Channel Islands mammoth | Mammuthus exilis | Santa Rosae island | Extinct (Late Pleistocene) | Columbian mammoth |

| Sardinian mammoth | Mammuthus lamarmorai | Sardinia | Extinct (Late Pleistocene) |  Steppe mammoth |

| Saint Paul Island woolly mammoth[22][23] | Mammuthus primigenius | Saint Paul Island, Alaska | Extinct (c. 3750 BC) | Woolly mammoth |

Siculo-Maltese elephants | Palaeoloxodon antiquus leonardi P. mnaidriensis P. melitensis P. falconeri | Sicily and Malta | Extinct |  Straight-tusked elephant (left) |

| Cretan elephants | Palaeoloxodon chaniensis P. creutzburgi | Crete | Extinct | |

Cyprus dwarf elephant | Palaeoloxodon cypriotes | Cyprus | Extinct (c. 9000 BC) | |

| Naxos dwarf elephant | Palaeoloxodon sp. | Naxos | Extinct | |

| Rhodes and Tilos dwarf elephant | Palaeoloxodon tiliensis | Rhodes and Tilos | Extinct | |

| Bumiayu dwarf sinomastodont[24] | Sinomastodon bumiajuensis | Bumiayu Island (now part of Java) | Extinct (Early Pleistocene) |  Sinomastodon |

Japanese stegodont[25] | Stegodon aurorae | Japan and Taiwan[26] | Extinct (Early Pleistocene) |  Chinese Stegodon |

| Greater Flores dwarf stegodont[3] | Stegodon florensis | Flores | Extinct (Late Pleistocene) |  Sundaland Stegodon |

| Javan dwarf stegodonts | Stegodon hypsilophus[24] S. semedoensis[27] S. sp.[24] | Java | Extinct (Quaternary) | |

| Mindanao pygmy stegodont[28] | Stegodon mindanensis | Mindanao and Sulawesi | Extinct (Middle Pleistocene) | |

| Sulawesi dwarf stegodont[24] | Stegodon sompoensis | Sulawesi | Extinct | |

| Lesser Flores dwarf stegodont[3] | Stegodon sondaari | Flores | Extinct (Middle Pleistocene) | |

| Sumba dwarf stegodont[29] | Stegodon sumbaensis | Sumba, Indonesia | Extinct (Middle Pleistocene) | |

| Timor dwarf stegodont[24] | Stegodon timorensis | Timor | Extinct | |

| Dwarf stegolophodont[30] | Stegolophodon pseudolatidens | Japan | Extinct (Miocene) | Stegolophodon |

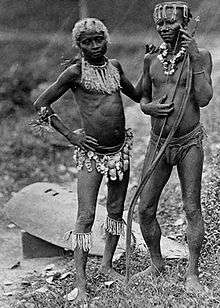

Primates

| Example | Binomial name | Native range | Status | Continental relative |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nosy Hara dwarf lemur[31] | Cheirogaleus sp. | Nosy Hara island off Madagascar | Unknown |  Dwarf lemurs |

Flores Man[32] | Homo floresiensis | Flores | Extinct (Late Pleistocene) |  Homo erectus |

Callao Man | Homo luzonensis[33][34] | Luzon, Philippines | Extinct (Late Pleistocene) | |

| Modern pygmies of Flores[35] | Homo sapiens | Flores | Extant | .jpg) Homo sapiens |

| Early Palau modern humans (disputed)[36] | Homo sapiens | Palau | Extinct (?) | |

Andamanese[37][38] | Homo sapiens | Andaman Islands | Extant | |

Sardinian macaque[39] | Macaca majori | Sardinia | Extinct (Pleistocene) |  Barbary macaque |

Zanzibar red colobus | Piliocolobus kirkii | Unguja | Endangered | Udzungwa red colobus |

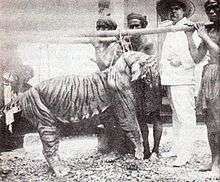

Carnivorans

| Example | Binomial name | Native range | Status | Continental relative | Insular / mainland length or mass ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Japanese wolf | Canis lupus hodophilax | Japan (excluding Hokkaido) | Extinct (AD 1905) |  Gray wolf | |

_Fig._1.png) Sardinian dhole (forward) | Cynotherium sardous | Corsica and Sardinia | Extinct (c. 8300 BC) |  Xenocyon | |

| Trinil dog | Mececyon trinilensis | Java | Extinct (Pleistocene) | ||

| Cozumel Island coati[13] | Nasua narica nelsoni | Cozumel | Critically endangered |  Yucatan white-nosed coati | |

Zanzibar leopard | Panthera pardus pardus | Unguja | Critically endangered or Extinct |  African leopard | |

Bali tiger | Panthera tigris sondaica | Bali | Extinct (c. AD 1940) | _close-up.jpg) Sumatran tiger | |

Javan tiger | Java | Extinct (c. AD 1975) | |||

Cozumel raccoon | Procyon pygmaeus | Cozumel | Critically endangered |  Common raccoon | |

Island fox | Urocyon littoralis | Six of the Channel Islands of California | Near Threatened | .jpg) Gray fox | LR ≈ 0.84 [lower-alpha 5] LR ≈ 0.75 [lower-alpha 6] |

| Cozumel fox | Urocyon sp. | Cozumel | Critically endangered or Extinct |

Non-ruminant ungulates

| Example | Binomial name | Native range | Status | Continental relative |

|---|---|---|---|---|

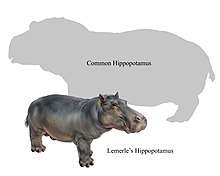

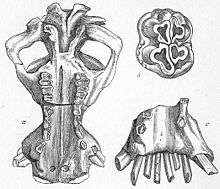

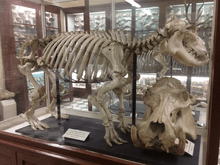

Malagasy dwarf hippopotamuses | Hippopotamus laloumena H. lemerlei H. madagascariensis | Madagascar | Extinct (c. AD 1000) |  Common hippopotamus |

| Bumiayu dwarf hippopotamus[24] | Hexaprotodon simplex | Bumiayu Island (now Java) | Extinct (Early Pleistocene) |  Asian hippopotamuses |

Cretan dwarf hippopotamus | Hippopotamus creutzburgi | Crete | Extinct (Middle Pleistocene) | European hippopotamus |

Maltese dwarf hippopotamus | Hippopotamus melitensis | Malta | Extinct (Pleistocene) | |

Cyprus dwarf hippopotamus | Hippopotamus minor | Cyprus | Extinct (c. 8000 BC) | |

Sicilian dwarf hippopotamus | Hippopotamus pentlandi | Sicily | Extinct (Pleistocene) | |

| Cozumel collared peccary[13] | Pecari tajacu nanus | Cozumel | Unknown |  Collared peccary |

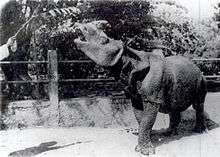

| Philippine rhinoceros[42] | Rhinoceros philippinensis | Luzon | Extinct (Middle Pleistocene) |  Javan rhinoceros |

Bovids

| Example | Binomial name | Native range | Status | Continental relative |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sicilian bison[25] | Bison priscus siciliae | Sicily | Extinct (Late Pleistocene) |  Steppe bison |

| Sicilian aurochs[43] | Bos primigenius siciliae[25] | Sicily | Extinct (Late Pleistocene) |  Eurasian aurochs |

| Cebu tamaraw | Bubalus cebuensis | Cebu, Philippines | Extinct | _(cropped).jpg) Wild water buffalo |

Lowland anoa | Bubalus depressicornis | Sulawesi and Buton, Indonesia | Endangered | |

Tamaraw | Bubalus mindorensis | Mindoro, Philippines | Critically endangered | |

Mountain anoa | Bubalus quarlesi | Sulawesi and Buton, Indonesia | Endangered | |

Balearic Islands cave goat | Myotragus balearicus | Majorca and Menorca | Extinct (after 3000 BC) | Gallogoral |

| Nesogoral[44] | Nesogoral spp. | Sardinia | Extinct | |

| Dahlak Kebir gazelle[45] | Nanger soemmerringi ssp. | Dahlak Kebir island, Eritrea | Vulnerable | _Gazella_soemmerringi_(white_background).png) Soemmerring's gazelle |

Cervids and relatives

| Example | Binomial name | Native range | Status | Continental relative |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Cretan dwarf megacerines[lower-alpha 7] | Candiacervus spp. | Crete | Extinct (Pleistocene) | Praemegaceros verticornis[9] |

Sardinian megacerine[9] (second from left) | Praemegaceros cazioti | Sardinia | Extinct (c. 5500 BC) | |

| Ryukyu dwarf deer[48] | Cervus astylodon | Ryukyu Islands | Extinct | _Manchurian_sika_white_background.png) Sika deer (?) Cervus praenipponicus (?) |

| Jersey red deer population[49] | Cervus elaphus jerseyensis | Jersey | Extinct (Pleistocene) |  Red deer |

Corsican red deer | Cervus elaphus corsicanus | Corsica and Sardinia | Near Threatened | |

| Pleistocene Sicilian deer[25] | Cervus siciliae | Sicily | Extinct (Late Pleistocene) | |

Hoplitomeryx[lower-alpha 8] | Hoplitomeryx spp. | Gargano Island | Extinct (Early Pliocene) | .jpg) Pecorans |

| Sicilian megacerine[25] | Megaloceros carburangelensis | Sicily | Extinct (Late Pleistocene) |  Irish elk |

Florida Key deer | Odocoileus virginianus clavium | Florida Keys | Endangered |  Virginia deer |

Svalbard reindeer | Rangifer tarandus platyrhynchus | Svalbard | Unknown |  Reindeer |

Philippine deer | Rusa marianna | Philippines | Vulnerable | _(7109798353).jpg) Sambar deer |

Plants

| Possible example | Binomial name | Native range | Status | Continental relative |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Insular elephant cacti[50][51] | Pachycereus pringlei | Remote islands in the Sea of Cortez (e.g. Santa Cruz, San Pedro Mártir) | Not evaluated | Mainland elephant cacti |

See also

| Wikinews has related news: |

- Island gigantism

- Foster's rule

- Dwarfing

- Franz Nopcsa

- Island tameness

- Pleistocene extinctions

Notes

- An example of noninsular phyletic dwarfism is the evolution of the dwarfed marmosets and tamarins among New World monkeys, culminating in the appearance of the smallest example, Cebuella pygmaea.[2]

- Based on the heights in Fig. 1 of Heupink et al., 2011[15]

- Based on maximum lengths of 2.5 m for the dwarf form[17] and 5.74 m for the mainland form[18]

- Based on maximum Tanahjampea python total lengths (TL) of 2.10 m for males and 3.35 m for females[19] and maximum southern Sumatra python snout to vent lengths (SVL) of 4.5 m for males and 6.1 m for females[20] with SVLs corrected to TLs by multiplying by a factor of 1.127, derived from the average relative tail length (0.113) of African and Indian rock pythons[21]

- For nearby mainland gray foxes[40]

- For mainland gray foxes in general[41]

- Like Hoplitomeryx, Candiacervus appears to be an unusual case in that members of this genus evolved into insular species of a wide range of sizes, not only dwarf forms but also some that might be considered giants.[46][47]

- Hoplitomeryx is evidently quite an unusual case, because members of this genus apparently evolved into both dwarf and giant insular forms on the same island(s).[46]

References

- Prothero, D. R.; Sereno, P. C. (Winter 1982). "Allometry and Paleoecology of Medial Miocene Dwarf Rhinoceroses from the Texas Gulf Coastal Plain". Paleobiology. 8 (1): 16–30. doi:10.1017/S0094837300004322. JSTOR 2400564.

- Perelman, P.; et al. (2011). "A Molecular Phylogeny of Living Primates". PLOS Genetics. 7 (3): 1–17. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1001342. PMC 3060065. PMID 21436896.

- Van Den Bergh, G. D.; Rokhus Due Awe; Morwood, M. J.; Sutikna, T.; Jatmiko; Wahyu Saptomo, E. (May 2008). "The youngest Stegodon remains in Southeast Asia from the Late Pleistocene archaeological site Liang Bua, Flores, Indonesia". Quaternary International. 182 (1): 16–48. Bibcode:2008QuInt.182...16V. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2007.02.001.

- Raia, P.; Meiri, S. (August 2006). "The island rule in large mammals: paleontology meets ecology". Evolution. 60 (8): 1731–1742. doi:10.1111/j.0014-3820.2006.tb00516.x.

- Keogh, J. S.; Scott, I. A. W.; Hayes, C. (January 2005). "Rapid and repeated origin of insular gigantism and dwarfism in Australian tiger snakes". Evolution. 59 (1): 226–233. doi:10.1111/j.0014-3820.2005.tb00909.x.

- Evans, A. R.; et al. (2012-01-30). "The maximum rate of mammal evolution". PNAS. 109 (11): 4187–4190. Bibcode:2012PNAS..109.4187E. doi:10.1073/pnas.1120774109. PMC 3306709. PMID 22308461. Retrieved 2011-02-11.

- Burness, G. P.; Diamond, J.; Flannery, T. (2001-12-04). "Dinosaurs, dragons, and dwarfs: The evolution of maximal body size". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 98 (25): 14518–14523. Bibcode:2001PNAS...9814518B. doi:10.1073/pnas.251548698. ISSN 0027-8424. JSTOR 3057309. PMC 64714. PMID 11724953.

- "Dwarf dinosaur island really did exist, scientists claim". Telegraph Media Group. 2010-02-22. Retrieved 2010-02-26.

- Benton, M. J.; Csiki, Z.; Grigorescu, D.; Redelstorff, R.; Sander, P. M.; Stein, K.; Weishampel, D. B. (2010-01-28). "Dinosaurs and the island rule: The dwarfed dinosaurs from Haţeg Island" (PDF). Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 293 (3–4): 438–454. Bibcode:2010PPP...293..438B. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2010.01.026. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-10. Retrieved 2017-07-30.

- Dyke, G. (2011-09-20). "The Dinosaur Baron of Transylvania". Scientific American. 305 (4): 80–83. Bibcode:2011SciAm.305c..80D. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican1011-80. PMID 22106812.

- Company, J. (2010). "Bone histology of the titanosaur Lirainosaurus astibiae (Dinosauria: Sauropoda) from the Latest Cretaceous of Spain". Naturwissenschaften. 98 (1): 67–78. doi:10.1007/s00114-010-0742-3.

- Carpenter, K. (2001) The Armored Dinosaurs. Indiana University Press, 526 pages.

- Cuarón, A. D.; Martínez-Morales, M. A.; McFadden, K. W.; Valenzuela, D.; Gompper, M. E. (2004). "The status of dwarf carnivores on Cozumel Island, Mexico". Biodiversity and Conservation. 13 (2): 317–331. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.511.2040. doi:10.1023/b:bioc.0000006501.80472.cc.

- Parker S (1984) The extinct Kangaroo Island Emu, a hitherto-unrecognised species. Bulletin of the British Ornithologists' Club 104: 19–22.

- Heupink, T. H.; Huynen, L.; Lambert, D. M. (2011). "Ancient DNA Suggests Dwarf and 'Giant' Emu Are Conspecific". PLoS ONE. 6 (4): e18728. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...618728H. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0018728. PMC 3073985. PMID 21494561.

- Glaw, F.; Köhler, J.; Townsend, T. M.; Vences, M. (2012-02-14). "Rivaling the World's Smallest Reptiles: Discovery of Miniaturized and Microendemic New Species of Leaf Chameleons (Brookesia) from Northern Madagascar". PLoS ONE. 7 (2): e31314. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...731314G. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0031314. PMC 3279364. PMID 22348069.

- de Lang R, Vogel G (2005). The Snakes of Sulawesi: A Field Guide to the Land Snakes of Sulawesi with Identification Keys. Frankfurt Contributions to Natural History Band 25, Edition Chimaira 2005. ISBN 3-930612-85-2. pp. 23-27, 198-201.

- Barker, D.G.; Barten, S.L.; Ehrsam, J.P.; Daddono, L. (2012). "The Corrected Lengths of Two Well-known Giant Pythons and the Establishment of a New Maximum Length Record for Burmese Pythons, Python bivittatus" (PDF). Bulletin of the Chicago Herpetological Society. 47 (1): 1–6. Retrieved 2020-03-02.

- Auliya, M.; Mausfeld, P.; Schmitz, A.; Böhme, W. (2002-04-09). "Review of the reticulated python (Python reticulatus Schneider, 1801) with the description of new subspecies from Indonesia". Naturwissenschaften. 89 (5): 201–213. Bibcode:2002NW.....89..201A. doi:10.1007/s00114-002-0320-4. PMID 12135085.

- Shine, R.; Harlow, P.S.; Keogh, J.S.; Boeadi, N.I. (1998). "The influence of sex and body size on food habits of a giant tropical snake, Python reticulatus ". Functional Ecology. 12 (2): 248–258. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2435.1998.00179.x.

- Sheehy, C.M.; Albert, J.S.; Lillywhite, H.B.; Van Damme, R. (2016). "The evolution of tail length in snakes associated with different gravitational environments". Functional Ecology. 30 (2): 244–254. doi:10.1111/1365-2435.12472.; see Table S1

- Schirber, Michael. Surviving Extinction: Where Woolly Mammoths Endured. Live Science. Imaginova Corporation. Retrieved 2007-07-20.

- The mammoths of Wrangel Island, north of Siberia, are no longer considered dwarfs. See: Tikhonov, Alexei; Larry Agenbroad; Sergey Vartanyan (2003). Comparative analysis of the mammoth populations on Wrangel Island and the Channel Islands. DEINSEA 9: 415–420. ISSN 0923-9308

- Aziz, F.; van den Bergh, G. D. (September 25, 1995). "A dwarf Stegodon from Sambungmacan (Central Java, Indonesia)". Proc. Kon. Ned. Akad. V. Wetensch. 98 (3): 229–241. Retrieved 2017-07-31.

- Sondaar, P. Y.; A.A.E. van der Geer (2005). "Evolution and Extinction of Plio-Pleistocene Island Ungulates". International Journal of the French Quaternary Association. 2: 241–256. Retrieved 2017-07-31.

- http://www.rhinoresourcecenter.com/pdf_files/129/1291330178.pdf

- Siswanto, S., & Noerwidi, S. (2014). PROBOSCIDEA FOSSIL FROM SEMEDO SITE: Its Correlation With Biostratigraphy and Human Arrival in Java. Berkala Arkeologi, 34(2).

- Zaim, Y. (20 August 2010). "Geological Evidence for the Earliest Appearance of Hominins in Indonesia". In Fleagle, J. G; Shea, J. J.; Grine, F. E.; Baden, A. L.; Leakey, R. E. (eds.). Out of Africa I: The First Hominin Colonization of Eurasia. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 106. ISBN 978-90-481-9036-2. OCLC 668096676.

- http://ro.uow.edu.au/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3055&context=smhpapers

- Saegusa, H. (2008). "Dwarf Stegolophodon from the Miocene of Japan: Passengers on sinking boats". Quaternary International. 182 (1): 49–62. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2007.08.001.

- "New group of dwarf lemurs may be world's rarest primate".

- Scientist to study Hobbit morphing, abc.net.au

- Wade, L. (2019-04-10). "New species of ancient human unearthed in the Philippines". Science. 364. doi:10.1126/science.aax6501.

- Détroit, F.; Mijares, A. S.; Corny, J.; Daver, G.; Zanolli, C.; Dizon, E.; Robles, E.; Grün, R.; Piper, P. J. (2019). "A new species of Homo from the Late Pleistocene of the Philippines". Nature. 568 (7751): 181–186. Bibcode:2019Natur.568..181D. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1067-9. PMID 30971845.

- Tucci, S.; et al. (2018-08-03). "Evolutionary history and adaptation of a human pygmy population of Flores Island, Indonesia". Science. 361 (6401): 511–516. Bibcode:2018Sci...361..511T. doi:10.1126/science.aar8486. PMC 6709593. PMID 30072539.

- "Ancient Small People on Palau Not Dwarfs, Study Says". National Geographic News. August 27, 2008.

- Gibbons, A. (2018). "Island living can shrink humans". Science. doi:10.1126/science.aau9750.

- Mondal, M.; Casals, F.; Xu, T.; Dall'Olio, G. M.; Pybus, M.; Netea, M. G.; Comas, D.; Laayouni, H.; Li, Q.; Majumder, P. P.; Bertranpetit, J. (2016). "Genomic analysis of Andamanese provides insights into ancient human migration into Asia and adaptation" (PDF). Nature Genetics. 48 (9): 1066–1070. doi:10.1038/ng.3621. hdl:10230/34401. PMID 27455350.

- Rook, L. (2008-12-31). "The first workshop on European fossil primate record (Siena and Grosseto, September 11-13, 2008) with an update on Italian studies in Paleoprimatology" (PDF). Atti Muss. Stor. Nat. Maremma (22): 129–143.

- Parfit, M.; Groo, M. (22 April 2020). "The uplifting tale of these tiny island foxes, nearly wiped out by disaster". NationalGeographic.com. National Geographic. Retrieved 2020-04-23.

- Moore, C.M.; Collins, P.W. (1995). "Mammalian Species – Urocyon littoralis" (PDF). 489: 1–7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 January 2012. Retrieved 16 September 2011. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Renema, Willem (2007). Biogeography, Time and Place: Distributions, Barriers and Islands. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 334. ISBN 978-1-4020-6374-9. OCLC 228153573.

- van Vuure, Cis (2005). Retracing the Aurochs: History, Morphology and Ecology of an Extinct Wild Ox. Coronet Books Incorporated. ISBN 978-954-642-235-4. OCLC 472741798.

- van der Geer, A.; Lyras, G; de Vos, J.; Dermitzakis, M. (14 February 2011). "Sardinia and Corsica". Evolution of Island Mammals: Adaptation and Extinction of Placental Mammals on Islands. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-4443-9128-2. OCLC 894698082.

- Chiozzi, G.; Bardelli, G.; Ricci, M.; De Marchi, G.; Cardini, A. (2014). "Just another island dwarf? Phenotypic distinctiveness in the poorly known Soemmerring's Gazelle, Nanger soemmerringii (Cetartiodactyla: Bovidae), of Dahlak Kebir Island". Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 111 (3): 603–620. doi:10.1111/bij.12239.

- Mazza, P.P.A.; Rossi, M.A.; Agostini, S. (2015). "Hoplitomerycidae (Late Miocene, Italy), an Example of Giantism in Insular Ruminants". Journal of Mammalian Evolution. 22: 271–277. doi:10.1007/s10914-014-9277-2.

- van der Geer, A.A.E. (2018). "Uniformity in variety: Antler morphology and evolution in a predator-free environment". Palaeontologia Electronica (21.1.9A): 1–31. doi:10.26879/834.

- Kaifu, Y.; Fujita, M.; Yoneda, M.; Yamasaki, S. (15 February 2015). "Pleistocene Seafaring and Colonization of the Ryukyu Islands, Southwestern Japan". In Kaifu, Y.; Izuho, M.; Goebel, T.; Sato, H.; Ono, A. (eds.). Emergence and Diversity of Modern Human Behavior in Paleolithic Asia. Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 978-1-62349-277-9. OCLC 985023261.

- Lister, A. M. (1989-11-30). "Rapid dwarfing of red deer on Jersey in the Last Interglacial". Nature. 342 (6249): 539–542. Bibcode:1989Natur.342..539L. doi:10.1038/342539a0. PMID 2685610.

- Wilder, B.T.; Felger, R.S. (30 September 2010). "Dwarf Giants, Guano, and Isolation: Vegetation and Floristic Diversity of San Pedro Mártir Island, Gulf of California, Mexico" (PDF). Proceedings of the San Diego Society of Natural History. 42: 1–24, see pp. 9–13. Retrieved 2020-01-05.

(p. 12) The dwarfing of the San Pedro Mártir plants seems to be due to a selection for shorter individuals to survive fierce tropical storms, possible root competition in such a dense forest, and the undefined effect of high levels of nitrogen and phosphorus from the abundant guano that might stunt growth. Genetic studies have not been undertaken...

- Burns, K.C. (May 2019). Evolution in Isolation: The Search for an Island Syndrome in Plants. Cambridge University Press. pp. 174–177. doi:10.1017/9781108379953. ISBN 978-1108379953. OCLC 1108160200.

(pp. 174-175) ... the extent to which its dwarfed stature is genetically determined, and an explanation for why insular dwarfism might be selectively advantageous, awaits additional study.