Bohemian Massif

The Bohemian Massif (Czech: Česká vysočina or Český masiv, German: Böhmische Masse or Böhmisches Massiv) is in the geology of Central Europe a large massif stretching over central Czech Republic, eastern Germany, southern Poland and northern Austria. It is surrounded by four ranges: the Ore Mountains (Krušné hory, or Erzgebirge) in the northwest, the Sudetes (for example Krkonoše, Hrubý Jeseník) in the northeast, the Bohemian-Moravian Highlands (Českomoravská vrchovina) in the southeast, and the Bohemian Forest (Šumava) in the southwest.[1] The massif encompasses a number of mittelgebirges and consists of crystalline rocks, which are older than the Permian (more than 300 million years old) and therefore deformed during the Variscan Orogeny.

Parts of the Sudetes, Krkonoše in particular, stand out from the ordinary mittelgebirge pattern by having up to four distinct levels of altitudinal zonation, glacial cirques, small periglacial landforms and an elevation significantly above the timber line.[2]

Geography

The landscapes in the Bohemian Massif are mostly dominated by rolling hills. North of the river Danube the topography is characterized by gentle valleys and broad, flat ridges and hilltops. The highest peaks on the Czech-Austrian borderline are the Plöckenstein (Plechý, 1,378 m) and Sternstein (1,125 m). The bedrock of acid gneiss and granite is weathered to brown soil (cambisols). In flat areas and valleys the groundwater had more influence on soil formation; in such places gley soils may be found too.

As in the other Variscan mittelgebirges of Central Europe, the valleys are more irregular and less pronounced as in the relatively young fold and thrust belt of the Alps. The plateaus are orographically more similar in morphology. Water gaps in the Bohemian Massif are the Wachau, the Strudengau and the valley of the Danube from Vilshofen over Passau and the Schlögener Schlinge till Aschach.

Geographical divisions

The Bohemian Massif in its broader sense can be subdivided as follows:

- Northern mountains (Ore Mountains and Sudetes, from west to east)

- Ore Mountains

- Elbe Sandstone Mountains

- Upper Lusatia (including the Lusatian Highlands and Lusatian Mountains)

- Giant Mountains

- High Ash Mountains

- Southwestern mountains (the Bohemian Forest in its wider sense)

- South and southeastern foothills:

- Gratzen Mountains

- Austrian Gneiss and Granite Highland, the high and deeply incised truncated highlands of the Austrian Mühlviertel and Waldviertel including the Weinsberg Forest and Bohemian Forest in other areas.

- Bohemian-Moravian Highlands between Budweis and Brünn

- Smaller strips are also found south of the Danube:

- Dunkelsteinerwald and Hiesberg in the Wachau

- Neustadtler Platte in the Strudengau

- Kürnberg Forest near Linz

- Sauwald between Eferding and Passau

- Neuburg Forest in Bavaria's countryside around Passau

Geology

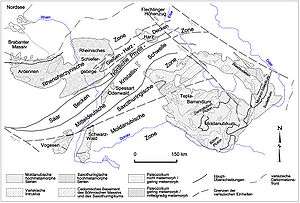

Tectonic subdivision

The internal tectonic structure of the Bohemian Massif was formed during the Variscan Orogeny. The Variscan Orogeny was a phase of mountain building and accretion of terranes that resulted from the closing of the Rheic Ocean when the two paleocontinents Gondwana (in the south) and Laurussia (in the north) collided. Most of the Bohemian Massif is often supposed to belong to a terrane called Cadomia or Armorica,[3] which also included the terranes of the Armorican Massif in western France. This supposedly formed a microcontinent that became sandwiched between the large continental masses north and south. The result of the Variscan Orogeny was that almost all continental mass became united in a supercontinent called Pangaea. From the Permian period onward the Variscan mountain belt eroded and became partly covered by younger sediments, with the exception of Variscan massifs like the Bohemian Massif.

The basement rocks and terranes of the Bohemian Massif are tectonically part of three main structural zones, which differ in metamorphic degrees, lithologies and tectonic styles. This tectonic subdivision was formed during the Variscan Orogeny.[4]

- The Saxothuringian Zone forms the northern parts of the massif. The northernmost part of the Saxothuringian Zone is the Mid-German Crystalline High, which is but rarely exposed in the Bohemian Massif. The northern boundary of this zone is assumed to be the Rheic suture which separates the former continental masses of Gondwana and Laurussia.[5]

- The Moldanubian Zone forms the central parts of the massif and has generally a higher grade than the Saxothuringian Zone. It includes the Teplá-Barrandian Terrane, which is assumed to have been a small microcontinent.

- The southeast of the massif forms a third unit, the Moravo-Silesian Zone. This zone includes the Brunovistulian Block, an allochthonous unit thrusted over the Moravo-Silesian crystalline rocks. Contradictionary to most parts of the Bohemian Massif, the Brunovistulian was originally part of or close to the southern part of Laurussia.[6]

Resources

Unlike other Variscan massifs in Central Europe the Bohemian Massif is not very rich in ores. The Harz Mountains further north in Germany, which are geologically part of the Rhenohercynian Zone, have more ore deposits. On the other hand, the Bohemian massif has many quarries where granite, granodiorite and diorite are won for use as decorative building stone.

References

- http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/71591/Bohemian-Massif

- Migoń, Piort (2008). "High-mountain elements in the geomorphology of the Sudetes, Bohemian Massif, and their significance". Geographia Polonica. 81 (1): 101–116.

- Linnemann et al. (2008b)

- A subdivision into Saxothuringian and Moldanubian zones was first introduced by Kossmat (1927). The usual subdivision described here can for example be found in Linnemann et al. (2008a)

- Linnemann et al. (2007)

- Finger et al. (2000) linked the Brunovistulian terrane with "Avalonia" (i.e. the southern part of Laurussia)

Further reading

- Finger, F.; Hanžl, P., Pin, C.; von Quadt, A. & Steyrer, H.P.; 2000: The Brunovistulian: Avalonian Precambrian sequence at the eastern Bohemian Massif: speculations on palinsplastic reconstruction, in: Franke, W.; Haak, V.; Oncken, O. & Tanner, D. (eds.): Orogenic Processes: Quantification and Modelling in the Variscan Belt, Geological Society of London Special Publication 179, pp 103–113.

- Kossmat, F.; 1927: Gliederung des varistischen Gebirgsbaues, Abhandlungen des Sächsischen Geologischen Landesamtes 1, pp. 1–39.

- Linnemann, U.; Romer, R.L.; Pin, C.; Aleksandrowski, P.; Buła, Z.; Geisler, T.; Kachlik, V.; Krzemińska, E.; Mazur, S.;Motuza, G.; Murphy, J.B.; Nance, R.D.; Pisarevsky, S.A.; Schulz, B.; Ulrich, J.; Wiszniewska, J.; Żaba, J. & Zeh, A.; 2008a: Chapter 2: Precambrian, in: McCann, T. (ed.): The Geology of Central Europe, The Geological Society, ISBN 1-86239-246-3.

- Linnemann, U.; D'Lemos, R.; Dorst, K.; Jeffries, T.; Gerdes, A.; Romer, R.L.; Samson, S.D. & Strachan, R.A.; 2008b: Chapter 3: Cadomian tectonics, in: McCann, T. (ed.): The Geology of Central Europe, The Geological Society, ISBN 1-86239-246-3.

- Linnemann, U.; Gerdes, A.; Drost, K. & Buschmann, B.; 2007: The Continuum between Cadomian orogenesis and opening of the Rheic Ocean: Constraints from LA-ICP-MS U-Pb Zircon dating and analysis of plate tectonic setting (Saxo-Thuringian Zone, northeastern Bohemian Massif, Germany, in: Linnemann, U.; Nance, R.D.; Kraft, P. & Zulauf, G. (eds.): The evolution of the Rheic Ocean, from Avalonian-Cadomian Active Margin to Alleghenian-Variscan Collision, Geological Society of America Special Paper 423, pp 61–96.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bohemian Massif. |