Datu

Datu is a title which denotes the rulers (variously described in historical accounts as chiefs, sovereign princes, and monarchs of numerous indigenous peoples throughout the Philippine archipelago.[1] The title is still used today, especially in Mindanao, Sulu and Palawan, but it was used much more extensively in early Philippine history, particularly in the regions of Central and Southern Luzon, the Visayas and Mindanao.[2][3][4][5][6][7]

| Pre-Colonial History of the Philippines |

|

|---|

| Barangay government |

| Ruling class (Maginoo): Datu (Lakan, Raja, Sultan) |

| Middle class: Timawa, Maharlika |

| Serfs, commoners and slaves (Alipin): Horohan, Alipin Namamahay, Alipin sa gigilid, Bulisik, Bulislis |

| The book of Maragtas |

| States in Luzon |

| Caboloan (Pangasinan) |

| Ma-i |

| Rajahnate of Maynila |

| Namayan |

| Tondo |

| States in the Visayas |

| Kedatuan of Madja-as |

| Kedatuan of Dapitan |

| Kingdom of Mactan |

| Rajahnate of Cebu |

| States in Mindanao |

| Rajahnate of Butuan |

| Sultanate of Sulu |

| Sultanate of Maguindanao |

| Sultanates of Lanao |

| Key figures |

|

| Religion in pre-colonial Philippines |

| History of the Philippines |

| Portal: Philippines |

Overview

In early Philippine history, Datus and a small group of their close relatives formed the "apex stratum" of the traditional three-tier social hierarchy of lowland Philippine societies.[4] Only a member of this birthright aristocracy (called "maginoo", "nobleza", "maharlika", or "timagua" by various early chroniclers) could become a Datu; members of this elite could hope to become a datu by demonstrating prowess in war and/or exceptional leadership.[4][5][3]

In large coastal polities such as those in Maynila, Tondo, Pangasinan, Cebu, Panay, Bohol, Butuan, Cotabato, Lanao, and Sulu,[4] several datus brought their loyalty-groups, referred to as "barangays" or "dulohan", into compact settlements which allowed greater degrees of cooperation and economic specialization. In such cases, datus of these barangays would then select the most senior or most respected among them to serve as what scholars call a "paramount leader, or "paramount datu."[5][3] The titles used by such paramount datu changed from case to case, but some of the most prominent examples were: Sultan in the most Islamized areas of Mindanao; Lakan among the Tagalog people; Thimuay among the Subanen people; Rajah in polities which traded extensively with Indonesia and Malaysia; or simply Datu in some areas of Mindanao and the Visayas.[8]

Proofs of Filipino royalty and nobility (Dugóng Bugháw) can be demonstrated only by clear blood descent from ancient native royal blood,[9][10] and in some cases adoption into a royal family.

Terminology

Datu (Baybayin: ), is the title for chiefs, sovereign princes, and monarchs throughout the Philippine archipelago.[1] The title is still used today, especially in Mindanao, Sulu and Palawan, but it was used much more extensively in early Philippine history, particularly in the regions of Central and Southern Luzon, the Visayas and Mindanao.[2][3][4][5][6] Other titles still used today are Lakan (Luzon), Apo in Central and Northern Luzon,[11] Sultan and Rajah, especially in Mindanao, Sulu and Palawan.[7] Depending upon the prestige of the sovereign royal family, the title of Datu could be equated to Royal Princes, European dukes, marquesses and counts.[12] In large ancient barangays, which had contacts with other southeast Asian cultures through trade, some Datus took the title Rajah or Sultan.[13]

The oldest historical records mentioning the title datu are the 7th century Srivijayan inscriptions such as Telaga Batu to describe lesser kings or vassalized kings.[14] The word datu is a cognate of the Malay terms Dato or Datuk and to the Fijian chiefly title of Ratu.[15]

Indigenous concepts, models and terminology concerning nobility and rulership among the peoples of the Philippine archipelago differed from one culture to the other, but lowland communities typically had a three-tier social structure aristocracy. In many of these societies, the word "Datu" meant the ruler of a particular social group, known as a Barangay, Dulohan, or Kedatuan.

History

In pre-Islamic times, the political leadership office was vested in a Rajaship in Manila and a Datuship elsewhere in the Philippines.[16]

Datu in Moro and Lumad societies in Mindanao

In the later part of the 1500s, the Spaniards took possession of most of Luzon and the Visayas, converting the lowland population to Christianity from their local indigenous religion. But although Spain eventually established footholds in northern and eastern Mindanao and the Zamboanga Peninsula, its armies failed to colonise the rest of Mindanao. This area was populated by Islamised peoples ("Moros" to the Spaniards) and by many non-Muslim indigenous groups now known as Lumad peoples.[17]

The Moro societies of Mindanao and Sulu

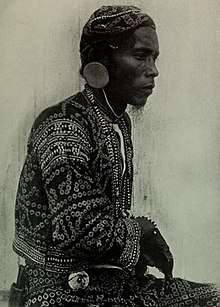

.png)

In the traditional structure of Moro societies, the sultans were the highest authority followed by the datus or rajah, with their rule being sanctioned by the Quran. The titles Datu and Rajah however, predates the coming of Islam. These titles were assimilated into the new structure under Islam. Datus were supported by their tribes. In return for tribute and labor, the datu provided aid in emergencies and advocacy in disputes with other communities and warfare through the Agama and Maratabat laws.

The Lumad societies of Mindanao

At the beginning of the 20th century, the Lumad peoples controlled an area that now covers 17 of Mindanao's 24 provinces—but by the 1980 census they constituted less than 6% of the population of Mindanao and Sulu. Heavy migration to Mindanao of Visayans, who have been settling in the Island for centuries, spurred by government-sponsored resettlement programmes, turned the Lumads into minorities. The Bukidnon province population grew from 63,470 in 1948 to 194,368 in 1960 and 414,762 in 1970, with the proportion of indigenous Bukidnons falling from 64% to 33% to 14%.[17]

There are 18 Lumad ethnolinguistic groups: Ata people, Bagobo, Banwaon, B’laan, Bukidnon, Dibabawon, Higaonon, Mamanwa, Mandaya, Manguwangan, Manobo, Mansaka, Subanon, Tagakaolo, Tasaday, Tboli, Teduray and Ubo.[17]

Lumad datus have involved themselves in protecting their homeland forests from illegal loggers during the past decades. Some have joined the New People's Army (NPA), a communist rebel group in the Country, for the cause of their people.[18] Others have resisted joining the Moro and Communist separatist movements.

A datu is still basic to the smooth functioning of Lumad and Moro societies today. They have continued to act as the community leaders in their respective tribes among a variety of Indigenous peoples in Mindanao. Moros, Lumads and Visayans now share with new settlers a homeland in Mindanao.[19]

Datu in pre-colonial principalities in the Visayas

In more affluent and powerful territorial jurisdictions and principalities in Visayas, e.g., Panay[20][21][22] Cebu and Leyte [23][24](which were never conquered by Spain but were accomplished as vassals by means of pacts, peace treaties, and reciprocal alliances),[25] the "Datu" Class was at the top of a divinely sanctioned and stable social order in a Sakop or Kinadatuan (Kadatuan in ancient Malay; Kedaton in Javanese; and Kedatuan in many parts of modern Southeast Asia), which is elsewhere commonly referred to also as barangay.[26] This social order was divided into three classes. The Kadatuan (members of the Visayan Datu Class) were compared by the Boxer Codex to the titled Lords (Señores de titulo) in Spain.[27] As Agalon or Amo (Lords),[28] the Datus enjoyed an ascribed right to respect, obedience, and support from their "Oripun" (Commoner) or followers belonging to the Third Order. These Datus had acquired rights to the same advantages from their legal "Timawa" or vassals (Second Order), who bind themselves to the Datu as his seafaring warriors. "Timawas" paid no tribute, and rendered no agricultural labor. They had a portion of the Datu's blood in their veins. The above-mentioned Boxer Codex calls these "Timawas": Knights and Hidalgos. The Spanish conquistador, Miguel de Loarca, described them as "free men, neither chiefs nor slaves". In the late 1600s, the Spanish Jesuit priest Fr. Francisco Ignatio Alcina, classified them as the third rank of nobility (nobleza).[29]

To maintain purity of bloodline, Datus marry only among their kind, often seeking high ranking brides in other Barangays, abducting them, or contracting brideprices in gold, slaves and jewelry. Meanwhile, the Datus keep their marriageable daughters secluded for protection and prestige.[30] These well-guarded and protected highborn women were called "Binokot",[31] the Datus of pure descent (four generations) were called "Potli nga Datu" or "Lubus nga Datu",[32] while a woman of noble lineage (especially the elderly) are addressed by the inhabitants of Panay as "Uray" (meaning: pure as gold), e.g., Uray Hilway.[33]

Datu in pre-colonial principalities in the Tagalog region

The different type of culture prevalent in Luzon gave a less stable and more complex social structure to the pre-colonial Tagalog barangays of Manila, Pampanga and Laguna. Enjoying a more extensive commerce than those in Visayas, having the influence of Bornean political contacts, and engaging in farming wet rice for a living, the Tagalogs were described by the Spanish Augustinian Friar Martin de Rada as more traders than warriors.[34]

The more complex social structure of the Tagalogs was less stable during the arrival of the Spaniards because it was still in a process of differentiating. In this society, the term Datu or Lakan, or Apo refers to the chief, but the noble class (to which the Datu belonged, or could come from) was the Maginoo Class. One could be born a Maginoo, but could become a 'Datu by personal achievement.[35]

Datu during the Spanish period

The Datu Class (First Estate) of the four echelons of Filipino Society at the time of contact with the Europeans (as described by Fr. Juan de Plasencia- a pioneer Franciscan missionary in the Philippines), was referred to by the Spaniards as the Principalía. Loarca,[36] and the Canon Lawyer Antonio de Morga, who classified the Society into three estates (ruler, ruled, slave), also affirmed the usage of this term and also spoke about the preeminence of the Principales.[37] All members of this Datu class were Principales,[38] whether they ruled or not.[39] San Buenaventura's 1613 Dictionary of the Tagalog Language defines three terms that clarify the concept of this Principalía:[37]

- Poón or punò (chief, leader) – principal or head of a lineage.

- Ginoó – a noble by lineage and parentage, family and descent.

- Maginoo – principal in lineage or parentage.

The Spanish term seňor (lord) is equated with all these three terms, which are distinguished from the nouveau riche imitators scornfully called Maygintao (man with gold or Hidalgo by gold, and not by lineage).[40]

Upon the Christianization of most parts of the Philippine Archipelago, the Datus retained their right to govern their territory under the Spanish Empire.[41] King Philip II of Spain, in a law signed June 11, 1594,[42] commanded the Spanish colonial officials in the Archipelago that these native royalties and nobilities be given the same respect, and privileges that they had enjoyed before their conversion. Their domains became self-ruled tributary barangays of the Spanish Empire.

The Filipino royals and nobles formed part of the exclusive, and elite ruling class, called the Principalía (Noble Class) of the Philippines. The Principalía was the class that constituted a birthright aristocracy with claims to respect, obedience, and support from those of subordinate status.[40]

With the recognition of the Spanish monarchs came the privilege of being addressed as Don or Doña.[43] – a mark of esteem and distinction in Europe reserved for a person of noble or royal status during the colonial period. Other honors and high regard were also accorded to the Christianized Datus by the Spanish Empire. For example, the Gobernadorcillos (elected leader of the Cabezas de Barangay or the Christianized Datus) and Filipino officials of justice received the greatest consideration from the Spanish Crown officials. The colonial officials were under obligation to show them the honor corresponding to their respective duties. They were allowed to sit in the houses of the Spanish Provincial Governors, and in any other places. They were not left to remain standing. It was not permitted for Spanish Parish Priests to treat these Filipino nobles with less consideration.[44]

The Gobernadorcillos exercised the command of the towns. They were Port Captains in coastal towns.[45] Their office corresponds to that of the alcaldes and municipal judges of the Iberian Peninsula. They performed at once the functions of judges and even of notaries with defined powers.[46] They also had the rights and powers to elect assistants and several lieutenants and alguaciles, proportionate in number to the inhabitants of the town.[46]

By the end of the 16th century, any claim to Filipino royalty, nobility, or hidalguía had disappeared into a homogenized, hispanized and Christianized nobility – the Principalía.[47] This remnant of the pre-colonial royal and noble families continued to rule their traditional domain until the end of the Spanish Regime. However, there were cases when succession in leadership was also done through election of new leaders (Cabezas de Barangay), especially in provinces near the central colonial government in Manila where the ancient ruling families lost their prestige and role. Perhaps proximity to the central power diminished their significance. However, in distant territories, where the central authority had less control and where order could be maintained without using coercive measures, hereditary succession was still enforced until Spain lost the Archipelago to the Americans. These distant territories remained Patriarchal societies, where people retained great respect for the Principalía.[48]

The Principalía was larger and more influential than the pre-conquest indigenous nobility. It helped create and perpetuate an oligarchic system in the Spanish colony for more than three hundred years.[49][50] The Spanish colonial government's prohibition for foreigners to own land in the Philippines contributed to the evolution of this form of oligarchy. In some provinces of the Philippines, many Spaniards and foreign merchants intermarried with the rich and landed Austronesian local nobilities. From these unions, a new cultural group was formed, the Mestizo class.[51] Their descendants emerged later to become an influential part of the government, and the Principalía. .[52]

Political Functions

Anthropologist Laura Lee Junker's[8] comparative analysis of historical accounts from cultures throughout the archipelago, depicts Datus functioning as:

- primary political authorities,

- war leaders,

- legal adjudicators,

- the de facto owners of agricultural products and sea resources within a district,

- the primary supporters of attached craft specialists,

- the overseers of intra-district and external trade, and

- the pivotal centers of regional resource mobilization systems.

Anthropologists like F. Landa Jocano[5] and Laura Lee Junker[8] and historians and historiographers like William Henry Scott[3] make a careful distinction between the nobility and aristocratic nature of the datus vis a vis the exercise of sovereign political authority. Although the Datus and Paramount Datus of early Philippine polities were a "birthright aristocracy" and were widely recognized "aristocratic" or "noble," comparable to the nobles and royals of the Spanish colonizers, the nature of their relationship with the members of their Barangay was less asymmetrical than in a monarchic political systems in other parts of the world.[5][53][54][8] Their control over territory was a function of their leadership of the Barangay and, in some local pre-colonial societies (mostly in Luzon), the concept of ruling was not that of "divine right."[8] Furthermore, their position was dependent on the common consent of the members of the Barangay's aristocratic Maginoo-class.[5] Although the position of Datu could be inherited, the Maginoo could decide to choose someone else to follow within their own class, if that other person proved a more capable war leader or political administrator.[5] Even "Paramount Datus" such as Lakans or Rajahs exercised only a limited degree of influence over the less-senior Datus they led, which did not include claims over the barangays and territories of these less-senior datus.[5] Antonio de Morga, in his work Sucesos de las Islas Filipinas, expounds on the degree to which early Philippine Datus could exercise their authority:

"There were no kings or lords throughout these islands who ruled over them as in the manner of our kingdoms and provinces; but in every island, and in each province of it, many chiefs were recognized by the natives themselves. Some were more powerful than others, and each one had his followers and subjects, by districts and families; and these obeyed and respected the chief. Some chiefs had friendship and communication with others, and at times wars and quarrels... When any of these chiefs was more courageous than others in war and upon other occasions, such a one enjoyed more followers and men; and the others were under his leadership, even if they were chiefs. These latter retained to themselves the lordship and particular government of their own following, which is called barangay among them. They had datos and other special leaders [mandadores] who attended to the interests of the barangay." [55]

Paramount Datus

The term Paramount Datu or Paramount ruler is a term applied by historians to describe the highest ranking political authorities in the largest lowland polities (see: Barangay state) or inter-polity alliance groups in early Philippine history,[56] most notably those in Maynila, Tondo, Confederation of Madja-as in Panay, Pangasinan, Cebu, Bohol, Butuan, Cotabato, and Sulu.[4][3]

Different cultures of the Philippine archipelago referred to the most senior datu or leader of the "Barangay state" or "Bayan"[3] using different titles. In Muslim polities such as Sulu and Cotabato, the Paramount Ruler was called a Sultan.[3] In Tagalog communities, the equivalent title was that of Lakan.[3] In communities which historically had strong political or trade connections with Indianized polities in Indonesia and Malaysia,[57] the Paramount Ruler was called a Rajah.[57][3] Among the Subanon people of the Zamboanga Peninsula, the most senior Thimuay is referred to as the "Thimuay Labi,"[58] or as Sulotan in more Islamized Subanon communities.[59] In some other portions of the Visayas and Mindanao, there was no separate name for the most senior ruler, so the Paramount Ruler was simply called a Datu,[57][3] although one Datu was identifiable as the most senior.[5][60]

Confer also: Non-sovereign monarchy.

Nobility

The noble or aristocratic nature of Datus and their relatives is asserted in folk origin myths,[29] was widely acknowledged by foreigners who visited the Philippine archipelago, and is upheld by modern scholarship.[8] Succession to the position of datu was often (although not always) hereditary,[8][5] and Datus derived their mandate to lead from their membership in an aristocratic class.[3] Records of Chinese traders and Spanish colonizers[57] describe Datus or Paramount Datus as sovereign princes and principals. Travellers who came to the Philippine archipelago from kingdoms or empires such as Song and Ming dynasty China, or 16th Century Spain, even initially referred to Datus or Paramount Datus as "kings," even though they later discovered that Datus did not exercise absolute sovereignty over the members of their Barangays.[8][5]

Indigenous conceptions of nobility and aristocracy

Both now and in early Philippine history, Filipino worldview had a conception of the self or individual being deeply and holistically connected to a larger community, expressed in the Language of Filipino psychology as "kapwa." [61] This indigenous conception of self strongly defined the roles and obligations played by individuals within their society.[62]

This differentiation of roles and obligations is also more broadly characteristic of Malayo-Polynesian [8] and Austronesian [63] cultures where, as Mulder[62] explains:

"...Social life is rooted in the immediate experience of a hierarchically ordered social arrangement based on the essential inequality of individuals and their mutual obligations to each other."

This "essential inequality of individuals and their mutual obligations to each other" informed the reciprocal relationships (expressed in the Filipino value of "utang na loob") that defined the three-tiered social structure typical among early Philippine peoples.

These settlements were characterized by a three-tier social structure, which, while slightly different between different cultures and polities, generally included a slave class (alipin/oripun), a class of commoners (timawa), and at the apex, an aristocratic or "noble" class. The noble class was exclusive, and its members were not allowed to marry outside of the aristocracy. Only members of this cognatically defined social class could rise to the position of Datu.

In some cases, such as the more developed Sakop or Kinadatuan in the Visayas (e.g., Panay, Bohol and Cebu), origin myths and other folk narratives firmly placed the datu and the aristocratic class at the top of a divinely sanctioned and stable social order.[64] These folk narratives portrayed the ancestors of Datus and other nobles as being created by an almighty deity, just like other human beings. But the behavior of these creations determined the social position of their descendants.[65]

This conception of social organization even continues to shape Philippine society today despite the introduction of western, externally democratic structures.[62] This has led some sociologists and political scientists to describe the Philippines' political structure as a cacique democracy.

Membership in the aristocratic class

The "authority, power, and influence" of the Datu (Adjali) emanated primarily from his recognized status within the noble class.[5]

Noble birth was not the only factor that determined a datu's political legitimacy, however. Success as a datu was dependent on one's "personal charisma, prowess in war, and wealth."[5]

Hereditary succession

The office of Datu was normally passed on through heredity,[8] and even in cases where it was not passed on through direct descent, only a fellow member of the aristocratic class could ascend to the position.[8] In large settlements (called Bayan among the Tagalogs) in which several datus and their barangays lived in close proximity, Paramount Datus were chosen by datus from amongst themselves in a more democratic way, but even this position as most senior among datus was often passed on through heredity.[5]

Antonio de Morga, in his work Sucesos de las Islas Filipinas, expounded on this succession through heredity, noting:

"These principalities and lordships were inherited in the male line and by succession of father and son and their descendants. If these were lacking, then their brothers and collateral relatives succeeded... When any of these chiefs was more courageous than others in war and upon other occasions, such a one enjoyed more followers and men; and the others were under his leadership, even if they were chiefs. These latter retained to themselves the lordship and particular government of their own following, which is called barangay among them. They had datos and other special leaders [mandadores] who attended to the interests of the barangay."[55]

Material affluence

Since the culture of the Pre-colonial societies in the Visayas, Northern Mindanao, and Luzon were largely influenced by Hindu and Buddhist cultures, the Datus who ruled these Principalities (such as Butuan Calinan, Ranau Gandamatu, Maguindanao Polangi, Cebu, Bohol, Panay, Mindoro and Manila) also share the many customs of royalties and nobles in Southeast Asian territories (with Hindu and Buddhist cultures), especially in the way they used to dress and adorn themselves with gold and silk. The Boxer Codex bears testimony to this fact. The measure of the prince's possession of gold and slaves was proportionate to his greatness and nobility.[66] The first Westerners, who came to the Archipelago, observed that there was hardly any "Indian" who did not possess chains and other articles of gold.[67]

Foreign Recognition of Nobility

The Spanish colonizers who came in the 1500s acknowledged the nobility of the aristocratic class within early Philippine societies.[2] Morga, for example, referred to them as "principalities."[48]

Once the Spanish colonial government had been established, the Spanish continued to recognize the descendants of pre-colonial datus as nobles, assigning them positions such as Cabeza de Barangay.[41] Spanish monarchs recognized their noble nature and origin.[68]

Popular portrayal as "monarchs"

Early misidentifications of pre-colonial polities in Luzon

When travellers – whether traders or colonizers – came to the Philippines from cultures which were under a sovereign monarch, these travellers often initially referred to the rulers of Philippine polities as "monarchs," implying recognition of their powers as sovereigns.[3]

Some early examples were the Song dynasty traders who came to the Philippines and referred to the ruler of Ma-i as a "Huang," meaning "King"[57] – an appellation later adopted by the Ming Dynasty courts when dealing with the Philippine archipelago cultures of their own time, such as Botuan and Luzon.[57]

Later, the Spanish expeditions of Magellan (in the 1520s) and Legaspi (in the 1570s) initially referred to Paramount Datus (Lakans, Rajahs, Sultans, etc.) as "Kings," although the Spanish stopped using this term when the Spanish under the command of Martin de Goiti first forayed out towards the polities in Bulacan and Pampanga in late 1571[69] and realized that these Kapampanan Datus had a choice not to obey the wishes of the Paramount Datus of Tondo (Lakandula) and Maynila (Rajahs Matanda and Sulayman), leading Lakandula and Sulayman to explain that there was "no single king over these lands",[69][3] and that the influence of Tondo and Maynila over the Kapampangan polities did not include either territorial claim or absolute command.[3]

Junker and Scott note that this misconception was natural, because both the Chinese and the Spanish came from cultures which had autocratic and imperial political structures. It was a function of language, since their respective sinocentrc and hispanocentric vocabularies were organized around worldviews which asserted the divine right of monarchs. As a result, they tended to project their beliefs into the peoples they encountered during trade and conquest.[8][3][70]

The concept of a sovereign monarchy was not unknown among the various early polities of the Philippine archipelago, since many of these settlements had rich maritime cultures and traditions, and travelled widely as sailors and traders. The Tagalogs, for example had the word "Hari" to describe a Monarch. As noted by Fray San Buenaventura (1613, as cited by Junker, 1990 and Scott, 1994), however, the Tagalogs only applied Hari (King) to foreign monarchs, such as those of the Javanese Madjapahit kingdoms, rather than to their own leaders. "Datu", "Rajah," "Lakan," etc., were distinct unique words to describe the powers and privilege of indigenous or local rulers and paramount rulers.[3]

Reappropriation of "royalty" in popular literature

Although early Philippine Datus, Lakans, Rajahs, Sultans, etc., were not sovereign in the political or military sense, they later came to be referred to as such due to the introduction of European literature during the Spanish colonial period.[71]

Because of the cultural and political discontinuities that came with colonization, playwrights of Spanish-era Philippine literature such as comedias and zarsuelas did not have precise terminologies to describe former Philippine rulership structures, and began appropriating European concepts, such as "king" or "queen" to describe them.[71] Because most Filipinos, even during precolonial times, related with political power structures as outsiders,[62] this new interpretation of "royalty" was accepted in the broadest sense, and the distinction between monarchy as a political structure vis a vis membership in a hereditary noble line or dynasty, was lost.[71]

This much-broader popular conception of monarchy, built on Filipino experiences of "great men" being socially separate from ordinary people[62] rather than the hierarchical technicalities of monarchies in the political sense, persists today. Common Filipino experience does not usually draw distinctions between aristocracy and nobility vis a vis sovereignty and monarchy. Datus, Lakans, Rajahs, Sultans, etc., are thus referred to as Kings or Monarchs in this non-technical sense, particularly in 20th century Philippine textbooks.[8]

The technical distinction between these concepts have only recently been highlighted again, by ethnohistorians, hisotoriographers and anthropologists belonging to the critical scholarship tradition,[8] since their concern is to capture indigenous meanings in the most accurate way possible.

Still this assessment of the nature of pre-colonial polities has to be viewed in the context of plurality of pre-colonial social structures existng in the Archipelago. It is obvious that those which existed in Luzon, vary from those that existed in the Visayas and Mindanao.

Also, the views of the various authors have to be assessed taking into consideration the background of social constructs, from which they assess the local pre-colonial polities. The historical, politico-cultural and chronological distance of these authors from actual events in the lives of the Filipino pre-colonials has to be taken into consideration. The view of an author living in the 20th century democratic country has a lot of difference from those who came from monarchic societies, who had actual contact with the pre-colonials, and who tried to qualify and approximate the conventions used in local hierarchical structures using the constructs of their time and context, in order to understand their actual experience of contact with what existed in the archipelago during the 16th Century.

Honorary datus

The title of "Honorary Datu" has also been conferred to certain foreigners and non-tribe members by the heads of local tribes and Principalities of ancient origin. During the colonial period, some of these titles carried with them immense legal privileges. For example, on January 22, 1878, Sultan Jamalul A'Lam of Sulu appointed the Baron de Overbeck (an Austrian who was then the Austro-Hungarian Empire's Consul-General in Hong Kong) as Datu Bendahara and as Rajah of Sandakan, with the fullest power of life and death over all the inhabitants.[72] On the other hand, in the Philippines, the Spaniards did not practice the granting of honorary titles. Instead, they created nobiliary titles over conquered territories in the Archipelago, in order to reward high Spanish colonial officials. These nobiiary titles are still used in Spain until now by the descendants of the original holders, e.g., Count of Jolo.[73][74][75] At present, arrangements such as this can no longer carry similar legal bearing under the Philippine laws.

The various tribes and claimants to the royal titles of certain indigenous peoples in the Philippines have their own particular or personal customs in conferring local honorary titles, which correspond to the specific and traditional social structures of some indigenous peoples in the Country.[76][77]

(N.B. In unhispanized, unchristianized and unislamized parts of the Philippines, there exist other structures of society, which do not have hierarchical classes.)[21][78]

Present day datus

The present day claimants of the title and rank of datu are of three types. The two types are mostly found in Mindanao, and the third type are those that live in the predominatly Catholic mainstream Filipino society. They are:

- The datus of the Muslim and Lumad indigenous tribal minorities, e.g., the datus of the Cuyunon Tribe of Palawan. Their rights are protected by a special law in the country, known as "The Indigenous Peoples Rights Act of 1997".[79]

- The datus and Sultan's of historical and influential pre-colonial polities that were not totally subjected to Spanish rule, e.g., Sultanate of Jolo, Sultanate of Maguindnao, who still claim at least the titles of their ancestors.

- The descendants of the Principalía, whose status and prerogatives as nobles were recognized and confirmed by the Spanish Empire.

Heirs to the rank of datu in the Catholic parts of the Philippines

In the mainstream Philippine society that is overwhelmingly Catholic, the descendants of the Principalía are the rightful claimants of the ancient sovereign royal and noble ranks of the pre-conquest kingdoms, principalities, and barangays of their ancestors. These descendants of the ancient ruling class are now among the landed aristocracy, intellectual elite, merchants, and politicians in the contemporary Filipino society. These people have had ancestors holding the titles of "Don" or "Doña" (which have also been used by Spanish royalties and nobilities) during the Spanish colonial period, as a compromise by the Spanish Crown to their previous indigenous titles.[43][80]

Philippine Constitution and the Law on Indigenous Minorities

Article VI, Section 31 of the 1987 Constitution explicitly forbids the creation, granting, and use of new royal or noble titles.[81] Titles of "Honorary Datu" conferred by various ethnic groups to certain foreigners and non-tribe members by local chieftains are only forms of local award or appreciation for some goods or services done to a local tribe or to the person of the chieftain, and are not legally binding. Any contrary claim is otherwise unconstitutional under Philippine law.

However, through the Indigenous Peoples' Rights Act of 1997, the Republic also protects the peculiar situation of tribal minorities and their traditional indigenous social structures. This special law allows members of indigenous minority tribes to be conferred with traditional leadership titles, including the title Datu, in a manner specified under the Law's Implementing rules and guidelines (Administrative Order No. 1, Series of 1998, of the National Commission on Indigenous Peoples specifically under Rule IV, Part I, Section 2, a-c), which read:

- a) Right to Confer Leadership Titles. The ICCs/IPs concerned, in accordance with their customary laws and practices, shall have the sole right to vest titles of leadership such as, but not limited to, Bae, Datu, Baylan, Timuay, Likid and such other titles to their members.

- b) Recognition of Leadership Titles. To forestall undue conferment of leadership titles and misrepresentations, the ICCs/IPs concerned, may, at their option, submit a list of their recognized traditional socio-political leaders with their corresponding titles to the NCIP. The NCIP through its field offices, shall conduct a field validation of said list and shall maintain a national directory thereof.

- c) Issuance of Certificates of Tribal Membership. Only the recognized registered leaders are authorized to issue certificates of tribal membership to their members. Such certificates shall be confirmed by the NCIP based on its census and records and shall have effect only for the purpose for which it was issued.

Pre-colonial Polities and Fons honorum

The fons honorum (source of honour) in the modern Philippine state is the sovereign Filipino people, who are equal in dignity under a democratic form of government.[81] The Philippine government grants state honours and decorations, and through the system of awards and decorations of its Armed Forces of the Philippines and the Philippine National Police. These honours do not grant or create titles of royalty or nobility, in accordance with the Constitution.

Deducing from the theory of Jean Bodin (1530–1596), a French jurist and political philosopher, it could be said that ancient Filipino royalties, who never relinquished their sovereign rights by voluntary means (according to opinions of some historians), of whom the sovereign powers over their territories (de facto sovereignty) passed on to the Spanish jura regalia through some disputed means, retain their "fons honorum" as part of their de jure sovereignty. Therefore, as long as the blood is alive in the veins of these royal houses, de jure sovereignty is alive as well—which means they can still bestow titles of nobility. However, the practical implications of this claim is unclear, e.g., in the case of usurpation of titles by other members of the bloodline.[82]

Heads of Dynasties (even the deposed ones) belong to one of the three kinds of sovereignty that has been existing in human society. The other two are: Heads of States (of all forms of government, e. g., monarchy, republican, communist, etc.), and Traditional Heads of the Church (both Roman Catholic and Orthodox). The authority that emanates from this last type is transmitted through an authentic Apostolic Succession, i.e., direct lineage of ordination and succession of Office from the Apostles (from St. Peter, in case of the Supreme Pontiff of the Roman Catholic Church – the Pope).[84][85]

These sovereign authorities exercise the following sovereign rights and powers: Ius Imperii (the right to command and rule a territory or a juridical entity); Ius Gladii (the right to impose obedience through command and also control armies); Ius Majestatis (the right to be honored and respected according to one's title); and Ius Honorum (the right to award titles, merits and rights). Considering the theory of Jean Bodin, that "Sovereignty is one and indivisible, it cannot be delegated, sovereignty us irrevocable, sovereignty is perpetual, sovereignty is a supreme power", one can argue about the rights of deposed dynasties, also as fons honorum. It can be said that their Ius Honorum depends on their rights as a family, and does not depend on the authority of the "de facto" government of a State. This is their de jure right. Even though it is not a de facto right, it is still a right.

But again, in case of conflict of norms on fons honorum in actual situations, the legislations of the de facto sovereign authority have precedence. All others are abrogated, unless otherwise recognized under the terms of such de facto authority.[86]

This is the view to reconsider when we study sovereignty based on the political impact of the 1987 Constitution of the Republic of the Philippines to the some polities that have been existing since the pre-colonial period, e.g., Sultanate of Sulu, Sultanate of Maguindanao.[87]

See also

- Barangay

- Barangay state

- Confederation of Madya-as

- Confederation of Sultanates in Lanao

- Datuk (Minangkabau)

- Hinduism in the Philippines

- History of the Philippines (before 1521)

- Rajahnate of Maynila

- Namayan

- Tondo (historical polity)

- Malay styles and titles

- Rajahnate of Butuan

- Rajahnate of Cebu

- Recorded list of Datus in the Philippines

- Sultanate of Lanao

- Sultanate of Maguindanao

- Sultanate of Sulu

- Taytay, Palawan

- Non-sovereign monarchy

- Federal monarchy

- Principalía

- Maginoo

- Philippine shamans

- Lakan

- Timawa

- Maharlika

References

- For more information about the social system of the Indigenous Philippine society before the Spanish colonization see Barangay in Enciclopedia Universal Ilustrada Europea-Americana, Madrid: Espasa-Calpe, S. A., 1991, Vol. VII, p.624: Los nobles de un barangay eran los más ricos ó los más fuertes, formándose por este sistema los dattos ó maguinoos, principes á quienes heredaban los hijos mayores, las hijas á falta de éstos, ó los parientes más próximos si no tenían descendencia directa; pero siempre teniendo en cuenta las condiciones de fuerza ó de dinero.

- Por otra parte, mientras en las Indias la cultura precolombiana había alcanzado un alto nivel, en Filipinas la civilización isleña continuaba manifestándose en sus estados más primitivos. Sin embargo, esas sociedades primitivas, independientes totalmente las unas de las otras, estaban en cierta manera estructuradas y se apreciaba en ellas una organización jerárquica embrionaria y local, pero era digna de ser atendida. Precisamente en esa organización local es, como siempre, de donde nace la nobleza. El indio aborigen, jefe de tribu, es reconocido como noble y las pruebas irrefutables de su nobleza se encuentran principalmente en las Hojas de Servicios de los militares de origen filipino que abrazaron la carrera de las Armas, cuando para hacerlo necesariamente era preciso demostrar el origen nobiliario del individuo. (On the other hand, while in the Indies pre-Columbian culture had reached a high level, in the Philippines the island civilization continued to manifest itself in its most primitive states. However, these primitive societies, totally independent of each other, were in some way structured and had an embryonic and local hierarchical organization in them, but it was worthy of being attended to. Precisely in that local organization is, as always, where the nobility is born. The Aboriginal Indian, chief of tribe, is recognized as noble and the irrefutable proofs of his nobility are found mainly in the Service Records of militarymen of the Filipino origin who embraced military career, when in order to do so it was necessary to prove the noble lineage of the individual.) de Caidenas y Vicent, Vicente, Las Pruebas de Nobleza y Genealogia en Filipinas y Los Archivios en Donde se Pueden Encontrar Antecedentes de Ellas in Heraldica, Genealogia y Nobleza en los Editoriales de Hidalguia, (1953–1993: 40 años de un pensamiento). Madrid: 1993, HIDALGUIA, p. 232.

- Scott, William Henry (1994). Barangay: Sixteenth Century Philippine Culture and Society. Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press. ISBN 971-550-135-4.

- Junker, Laura Lee (1998). "Integrating History and Archaeology in the Study of Contact Period Philippine Chiefdoms". International Journal of Historical Archaeology. 2 (4): 291–320. doi:10.1023/A:1022611908759.

- Jocano, F. Landa (2001). Filipino Prehistory: Rediscovering Precolonial Heritage. Quezon City: Punlad Research House, Inc. ISBN 971-622-006-5.

- “También fundó convento el Padre Fray Martin de Rada en Araut- que ahora se llama el convento de Dumangas- con la advocación de nuestro Padre San Agustín...Está fundado este pueblo casi a los fines del río de Halaur, que naciendo en unos altos montes en el centro de esta isla (Panay)...Es el pueblo muy hermoso, ameno y muy lleno de palmares de cocos. Antiguamente era el emporio y corte de la más lucida nobleza de toda aquella isla...Hay en dicho pueblo algunos buenos cristianos...Las visitas que tiene son ocho: tres en el monte, dos en el río y tres en el mar...Las que están al mar son: Santa Ana de Anilao, San Juan Evangelista de Bobog, y otra visita más en el monte, entitulada Santa Rosa de Hapitan.” Gaspar de San Agustin, O.S.A., Conquistas de las Islas Filipinas (1565–1615), Manuel Merino, O.S.A., ed., Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Cientificas: Madrid 1975, pp. 374–375.

- In Mindanao, there have been several Sultanates. The Sultanate of Maguindanao, Sultanate of Sulu, and Confederation of Sultanates in Lanao are among those more known in history. Cf. "Archived copy". Archived from the original on March 25, 2012. Retrieved February 13, 2012.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Junker, Laura Lee (1990). "The Organization of IntraRegional and LongDistance Trade in PreHispanic Philippine Complex Societies". Asian Perspectives. 29 (2): 167–209.

- Cf. Vicente de Cadenas y Vicent, "Las Pruebas de Nobleza y Genealogia en Filipinas y Los Archivios en Donde se Pueden Encontrar Antecedentes de Ellas" in "Heraldica, Genealogia y Nobleza en los Editoriales de «Hidalguia»", Madrid: 1993, Graficas Ariás Montano, S.A.-MONTOLES, pp. 232–235.

- By the end of the 16th century, any claim to Filipino royalty, nobility, or hidalguía had disappeared into a homogenized, hispanized, and Christianized nobility – the Principalía. Cf. William Henry Scott, Cracks in the Parchment Curtain, Quezon City: 1998, pp. 117–118. Cf. Also this article's section on Datu during the Spanish Regime and also the section on Prohibition of New Royal and Noble Titles in the Philippine Constitution.

- The Olongapo Story, July 28, 1953 – Bamboo Breeze – Vol.6, No.3

- "There were no kings or lords throughout these islands who ruled over them as in the manner of our kingdoms and provinces; but in every island, and in each province of it, many chiefs were recognized by the natives themselves. Some were more powerful than others, and each one had his followers and subjects, by districts and families; and these obeyed and respected the chief. Some chiefs had friendship and communication with others, and at times wars and quarrels. These principalities and lordships were inherited in the male line and by succession of father and son and their descendants. If these were lacking, then their brothers and collateral relatives succeeded... When any of these chiefs was more courageous than others in war and upon other occasions, such a one enjoyed more followers and men; and the others were under his leadership, even if they were chiefs. These latter retained to themselves the lordship and particular government of their own following, which is called barangay among them. They had datos and other special leaders [mandadores] who attended to the interests of the barangay." Antonio de Morga, The Project Gutenberg EBook of History of the Philippine Islands, Vols. 1 and 2, Chapter VIII.

- Examples of Datus who took the title Rajah were Rajah Soliman, Rajah Matanda, and Rajah Humabon. Cf. Landa Jocano, Filipino Prehistory, Manila: 2001, p.160.

- Casparis, J.G., (1956), Prasasti Indonesia II: Selected Inscriptions from the 7th to the 9th Century A.D., Dinas Purbakala Republik Indonesia, Bandung: Masa Baru.

- "Austronesian Comparative Dictionary: Datu". Retrieved June 15, 2020.

- Tan, Samuel K. (2008). A History of the Philippines. UP Press. pp. 36–37. ISBN 978-971-542-568-1.

- Mindanao Land of Promise (archived from the original Archived October 28, 2008, at the Wayback Machine on October 28, 2008)

- "Lumad chieftain abandons rebel movement in Agusan". Manila Bulletin. April 22, 2009.

- Chieftains

- Historians classify four types of unhispanized societies in the Philippines, some of which still survive in remote and isolated parts of the Country:

- Classless societies

- Warrior societies, characterized by a distinct warrior class, in which membership is won by personal achievement, entails privilege, duty, and prescribed norms of conduct, and is requisite for community leadership

- Petty plutocracies dominated socially and politically by a recognized class of rich men who attain membership through birthright, property, and by performing specified ceremonies. They are "petty" because their authority is localized, being extended by neither absentee landlordism nor territorial subjugation

- Principalities: Scott's book mostly mentions examples in Mindanao, however, this form of society was predominant on the plains of the Visayan Islands and Luzon, during the pre-conquest era. Cf. William Henry Scott, Cracks in the Parchment Curtain, Quezon City: 1998, p. 139.

- Cf. William Henry Scott, Cracks in the Parchment Curtain, Quezon City: 1998, pp. 127–147.

- During the early part of the Spanish colonization of the Philippines the Spanish Augustinian Friar, Gaspar de San Agustín, O.S.A., describes Iloilo and Panay as one of the most populated islands in the archipelago and the most fertile of all the islands of the Philippines. He also talks about Iloilo, particularly the ancient settlement of Halaur, as site of a progressive trading post and a court of illustrious nobilities. The friar says: Es la isla de Panay muy parecida a la de Sicilia, así por su forma triangular come por su fertilidad y abundancia de bastimentos... Es la isla más poblada, después de Manila y Mindanao, y una de las mayores, por bojear más de cien leguas. En fertilidad y abundancia es en todas la primera... El otro corre al oeste con el nombre de Alaguer [Halaur], desembocando en el mar a dos leguas de distancia de Dumangas...Es el pueblo muy hermoso, ameno y muy lleno de palmares de cocos. Antiguamente era el emporio y corte de la más lucida nobleza de toda aquella isla...Mamuel Merino, O.S.A., ed., Conquistas de las Islas Filipinas (1565–1615), Madrid: Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Cientificas, 1975, pp. 374–376.

- The encomienda of 1604 shows that many coastal barangays in Panay, Leyte , Bohol and Cebu were flourishing trading centers. Some of these barangays had large populations. In Panay, some barangays had 20,000 inhabitants; in Leyte (Baybay) 15,000 inhabitants; and in Cebu, 3,500 residents. There were smaller barangays with fewer people. But these were generally inland communities; or if they were coastal, they were not located in areas good for business pursuits. Cf. F. Landa Jocano, Filipino Prehistory: Rediscovering Precolonial Heritage (1998), pp. 157–158, 164

- Leyte and Cebu, Pampanga, Pangasinan, Pasig, Laguna, and Cagayan River were flourishing trading centers. Some of these barangays had large populations. In Panay, some barangays had 20,000 inhabitants; in Leyte (Baybay), 15,000 inhabitants; in Cebu, 3,500 residents; in Vitis (Pampanga), 7,000 inhabitants; Pangsinan, 4,000 residents. There were smaller barangays with fewer people. But these were generally inland communities; or if they were coastal, they were not located in areas good for business pursuits. Cf. F. Landa Jocano, Filipino Prehistory: Rediscovering Precolonial Heritage (1998), pp. 157–158, 164

- Cf. William Henry Scott, Cracks in the Parchment Curtain, Quezon City: 1998, p. 4. Also cf. Antonio Morga, Sucessos de las Islas Filipinas, 2nd ed., Paris: 1890, p. xxxiii.

- The word "sakop" means "jurisdiction", and "Kinadatuan" refers to the realm of the Datu – his principality.

- William Henry Scott, Cracks in the Parchment Curtain, Quezon City: 1998, pp. 102 and 112

- In Panay, even at present, the landed descendants of the Principales are still referred to as Agalon or Amo by their tenants. However, the tenants are no longer called Oripon (in Karay-a, i.e., the Ilonggo sub-dialect) or Olipun (in Sinâ, i.e., Ilonggo spoken in the lowlands and cities). Instead, the tenants are now commonly referred to as Tinawo (subjects)

- William Henry Scott, Cracks in the Parchment Curtain, Quezon City: 1998, pp. 112- 118.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on August 21, 2010. Retrieved July 22, 2011.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) Seclusion and Veiling of Women: A Historical and Cultural Approach

- Cf. Emma Helen Blair and James Alexander Robertson, The Philippine Islands (1493–1898), Cleveland: The A.H. Clark Company, 1903, Vol. XXIX, pp. 290–291.

- William Henry Scott, Cracks in the Parchment Curtain, Quezon City: 1998, p. 113.

- Cf. Emma Helen Blair and James Alexander Robertson, The Philippine Islands (1493–1898), Cleveland: The A.H. Clark Company, 1903, Vol. XXIX, p. 292.

- Cf. William Henry Scott, Cracks in the Parchment Curtain, Quezon City: 1998, pp. 124–125.

- Cf. William Henry Scott, Cracks in the Parchment Curtain, Quezon City: 1998, p. 125.

- Cf. Emma Helen Blair and James Alexander Robertson, The Philippine Islands (1493–1898), Cleveland: The A.H. Clark Company, 1903, Vol. V, p. 155.

- Cf. William Henry Scott, Cracks in the Parchment Curtain, Quezon City: 1998, p. 99.

- Tous les descendants de ces chefs étaient regardés comme nobles et exempts des corvées et autres services auxquels étaient assujettis les roturiers que l on appelait "timaguas". Les femmes étaient nobles comme les hommes.J. Mallat, Les Philippines, histoire, geographie, moeurs, agriculture, industrie et commerce des Colonies espagnoles dans l'oceanie, Paris: 1846, p. 53.

- The Real Academia Espaňola defines Principal as a "person or thing that holds first place in value or importance, and is given precedence and preference before others". This Spanish term best describes the Datu class of the society in the Archipelago, which the Europeans came in contact with. Cf. William Henry Scott, Cracks in the Parchment Curtain, Quezon City: 1998, p. 99.

- Cf. William Henry Scott, Cracks in the Parchment Curtain, Quezon City: 1998, p. 100.

- L'institution des chefs de barangay a été empruntée aux Indiens chez qui on l a trouvée établie lors de la conquête des Philippines; ils formaient, à cette époque une espèce de noblesse héréditaire. L'hérédité leur a été conservée aujourd hui: quand une de ces places devient vacante, la nomination du successeur est faite par le surintendant des finances dans les pueblos qui environnent la capitale, et, dans les provinces éloignées, par l alcalde, sur la proposition du gobernadorcillo et la présentation des autres membres du barangay; il en est de même pour les nouvelles créations que nécessite de temps à autre l augmentation de la population. Le cabeza, sa femme et l aîné de ses enfants sont exempts du tributo; après trois ans de service bien fait, on leur accorde le titre de "don" et celui de "pasado"; et ils demeurent exempts de tout service personnel; ils peuvent être élus gobernadorcillos. Les votes sont pris au scrutin secret et la moindre infraction aux règlements entraîne la nullité de l'élection. (The institution of the Chefs de Barangay was borrowed from the Indians with whom it was found established during the conquest of the Philippines; At that time they formed a kind of hereditary nobility. Heredity has been preserved to them to-day; when one of these places becomes vacant, the appointment of the successor is made by the superintendent of finance in the pueblos which surround the capital, and in the distant provinces by the alcalde, The proposal of the gobernadorcillo and the presentation of the other members of the barangay; It is the same for the new creations that the population needs from time to time. The cabeza, his wife and the eldest of his children are exempt from tributo. After three years of good service, they are granted the title of "don" and that of "pasado"; and they remain free from any personal service; they can be elected gobernadorcillos. Votes are taken by secret ballot and the slightest violation of the regulations results in the nullity of the election.) MALLAT de BASSILAU, Jean (1846). Les Philippines: Histoire, géographie, moeurs. Agriculture, industrie et commerce des Colonies espagnoles dans l'Océanie (2 vols) (in French). Paris: Arthus Bertrand Éd. ISBN 978-1143901140. OCLC 23424678, p. 356..

- “It is not right that the Indian chiefs of Filipinas be in a worse condition after conversion; rather they should have such treatment that would gain their affection and keep them loyal, so that with the spiritual blessings that God has communicated to them by calling them to His true knowledge, the temporal blessings may be added and they may live contentedly and comfortably. Therefore, we order the governors of those islands to show them good treatment and entrust them, in our name, with the government of the Indians, of whom they were formerly lords. In all else the governors shall see that the chiefs are benefited justly, and the Indians shall pay them something as a recognition, as they did during the period of their paganism, provided it be without prejudice to the tributes that are to be paid us, or prejudicial to that which pertains to their encomenderos.” Felipe II, Ley de Junio 11, 1594 in Recapilación de leyes, lib. vi, tit. VII, ley xvi. Also cf. Emma Helen Blair and James Alexander Robertson, The Philippine Islands (1493–1898), Cleveland: The A.H. Clark Company, 1903, Vol. XVI, pp. 155–156.The original text in Spanish (Recapilación de leyes) says: No es justo, que los Indios Principales de Filipinas sean de peor condición, después de haberse convertido, ántes de les debe hacer tratamiento, que los aficione, y mantenga en felicidad, para que con los bienes espirituales, que Dios les ha comunicado llamándolos a su verdadero conocimiento, se junten los temporales, y vivan con gusto y conveniencia. Por lo qua mandamos a los Gobernadores de aquellas Islas, que les hagan buen tratamiento, y encomienden en nuestro nombre el gobierno de los Indios, de que eran Señores, y en todo lo demás procuren, que justamente se aprovechen haciéndoles los Indios algún reconocimiento en la forma que corría el tiempo de su Gentilidad, con que esto sin perjuicio de los tributos, que á Nos han de pagar, ni de lo que á sus Encomenderos. Juan de Ariztia, ed., Recapilación de leyes, Madrid (1723), lib. vi, tit. VII, ley xvi. This reference can be found at the library of the Estudio Teologico Agustiniano de Valladolid in Spain.

- Cf. Emma Helen Blair and James Alexander Robertson, The Philippine Islands (1493–1898), Cleveland: The A.H. Clark Company, 1903, Vol. XL, p. 218.

- Emma Helen Blair and James Alexander Robertson, The Philippine Islands (1493–1898), Cleveland: The A.H. Clark Company, 1903, Vol. XXVII, pp. 296–297.

- Gobernadorcillo in Encyclopedia Universal Ilustrada Europeo-Américana, Madrid: Espasa-Calpe, S.A.,1991, Vol. XLVII, p. 410

- Cf. Emma Helen Blair and James Alexander Robertson, The Philippine Islands (1493–1898), Cleveland: The A.H. Clark Company, 1903, Vol. XVII, p. 329.

- William Henry Scott, Cracks in the Parchment Curtain, Quezon City: 1998, pp. 117–118.

- Esta institucion (Cabecería de Barangay), mucho más antigua que la sujecion de las islas al Gobierno, ha merecido siempre las mayores atencion. En un principio eran las cabecerías hereditarias, y constituian la verdadera hidalguía del país; mas del dia, si bien en algunas provincias todavía se tramiten por sucesion hereditaria, las hay tambien eleccion, particularmente en las provincias más inmediatas á Manila, en donde han perdido su prestigio y son una verdadera carga. En las provincias distantes todavía se hacen respetar, y allí es precisamente en donde la autoridad tiene ménos que hacer, y el órden se conserva sin necesidad de medidas coercitivas; porque todavía existe en ellas el gobierno patriarcal, por el gran respeto que la plebe conserva aún á lo que llaman aquí principalía. (This institution (Cabecería de Barangay), much older than the subjection of the islands to the Government, has always deserved the greatest attention. In the beginning were the hereditary headings, and constituted the true hidalguía of the country; But in the provinces, although they are still processed by hereditary succession, there are also elections, particularly in the provinces closest to Manila, where they have lost their prestige and are a real burden. In the distant provinces they are still respected, and that is precisely where authority has less to do, and the order is preserved without the need for coercive measures; Because the patriarchal government still exists in them, because of the great respect which the plebs still hold to what they call here "principal") FERRANDO, Fr Juan & FONSECA OSA, Fr Joaquin (1870–1872). Historia de los PP. Dominicos en las Islas Filipinas y en las Misiones del Japon, China, Tung-kin y Formosa (Vol. 1 of 6 vols) (in Spanish). Madrid: Imprenta y esteriotipia de M Rivadeneyra. OCLC 9362749.

- Cf. footnote n.3.

- Cf. Emma Helen Blair and James Alexander Robertson, The Philippine Islands (1493–1898), Cleveland: The A.H. Clark Company, 1903, Vol. XVII, p. 331; Ibid., Vol. XL, p. 218.

- Cf. also Encomienda; Hacienda.

- Cf. The Impact of Spanish Rule in the Philippines in www.seasite.niu.edu."Archived copy". Archived from the original on October 1, 2007. Retrieved October 1, 2007.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- McCoy, Alfred W. (1983) An Anarchy of Families: State and Family in the Philippines.

- Anderson,Benedict. (1983) Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism.

- Morga, Antonio de (1609). Succesos de las Islas Filipinas.

- "Pre-colonial Manila". Malacañang Presidential Museum and Library. Malacañang Presidential Museum and Library Araw ng Maynila Briefers. Presidential Communications Development and Strategic Planning Office. June 23, 2015. Archived from the original on March 9, 2016. Retrieved April 27, 2017.

- Scott, William Henry (1984). Prehispanic Source Materials for the Study of Philippine History. Quezon City: New Day Publishers. ISBN 978-9711002268.

- Imbing, Thimuay Mangura Vicente L.; Viernes-Enriquez, Joy (1990). "A Legend of the Subanen "Buklog"". Asian Folklore Studies. 49 (1): 109–123. doi:10.2307/1177951. JSTOR 1177951.

- Buendia, Rizal; Mendoza, Lorelei; Guiam, Rufa; Sambeli, Luisa (2006). Mapping and Analysis of Indigenous Governance Practices in the Philippines and Proposal for Establishing an Indicative Framework for Indigenous People's Governance: Towards a Broader and Inclusive Process of Governance in the Philippines (PDF). Bangkok: United Nations Development Programme.

- Scott, William Henry (1992). Looking for the Prehispanic Filipino and Other Essays in the Philippine History. Quezon City: New Day Publishers. ISBN 971-10-0524-7.

- de Guia, Katrin (2005). Kapwa: The Self in the Other: Worldviews and Lifestyles of Filipino Culture-Bearers. Pasig City: Anvil Publishing, Inc. p. 378. ISBN 971271490X.

- Mulder, Niels (2013). "Filipino Identity: The Haunting Question". Journal of Current Southeast Asian Affairs, 32, 1, 55–80. 32 (1): 66–80. doi:10.1177/186810341303200103. ISSN 1868-1034.

For most Southeast Asians, social life is rooted in the immediate experience of a hierarchically ordered social arrangement based on the essential inequality of individuals and their mutual obligations to each other. This tangible world blends into the surrounding (not morally obliging) space of nature and wider society that appears as the property of others – be they religious figures, politicians, officials, landlords and/or economic powerholders. Whereas this area may be seen as a “public in itself”, it is not experienced as “of the public” or “for itself”. It is the vast territory where “men of prowess” (Wolters 1999: 18–19) compete for power, the highly admired social good (King 2008: 177). Accordingly, society is reduced to an aggregate of person-to-person bonds that are supposedly in good order if everybody lives up to his or her ethics of place.

- Benitez-Johannot, Purissima, ed. (September 16, 2011). Paths Of Origins: The Austronesian Heritage In The Collections Of The National Museum Of The Philippines, The Museum Nasional Of Indonesia, And The Netherlands Rijksmuseum Voor Volkenkunde. Makati City, Philippines: Artpostasia Pte Ltd. ISBN 9789719429203.

- SCOTT, William Henry (1982). Cracks in the Parchment Curtain, and Other Essays in Philippine History. Quezon City: New Day Publishers. ISBN 978-9711000004. OCLC 925966, p. 4.

- Demetrio, Francisco R.; Cordero-Fernando, Gilda; Nakpil-Zialcita, Roberto B.; Feleo, Fernando (1991). The Soul Book: Introduction to Philippine Pagan Religion. GCF Books, Quezon City. ASIN B007FR4S8G.

- Cf. Report of the Franciscan Fray Letona to Fray Diego Zapata, high Official of the Franciscan Order and of the Inquisition in Emma Helen Blair and James Alexander Robertson, The Philippine Islands (1493–1898), Cleveland: The A.H. Clark Company, 1903, Vol. XXIX, p. 281.

- Cf. Emma Helen Blair and James Alexander Robertson, The Philippine Islands (1493–1898), Cleveland: The A.H. Clark Company, 1905, Vol. XXXVI, p. 201.

- En el Título VII, del Libro VI, de la Recopilación de las leyes de los reynos de Las Indias, dedicado a los caciques, podemos encontrar tres leyes muy interesantes en tanto en cuanto determinaron el papel que los caciques iban a desempeñar en el nuevo ordenamiento social indiano. Con ellas, la Corona reconocía oficialmente los derechos de origen prehispánico de estos principales. Concretamente, nos estamos refiriendo a las Leyes 1, 2, dedicadas al espacio americano . Y a la Ley 16, instituida por Felipe II el 11 de junio de 1594 -a similitud de las anteriores-, con la finalidad de que los indios principales de las islas Filipinas fuesen bien tratados y se les encargase alguna tarea de gobierno. Igualmente, esta disposición hacía extensible a los caciques filipinos toda la doctrina vigente en relación con los caciques indianos...Los principales pasaron así a formar parte del sistema político-administrativo indiano, sirviendo de nexo de unión entre las autoridades españolas y la población indígena. Para una mejor administración de la precitada población, se crearon los «pueblos de indios» -donde se redujo a la anteriormente dispersa población aborigen- (In Title VII, Book VI, of the Compilation of the laws of the kingdoms of the Indies, dedicated to the caciques, we can find three very interesting laws insofar as they determined the role that the caciques were going to play in the new order Social background. With them, the Crown officially recognized the rights of pre-Hispanic origin of these principals. Specifically, we are referring to Laws 1, 2, dedicated to American space. And to Law 16, instituted by Philip II on June 11, 1594 – the similarity of the previous ones – in order that the principal Indians of the Philippine Islands be treated well and be entrusted with some task of government. Likewise, this provision extended to the Filipino caciques all the doctrine in force in relation to the Indian chieftains ... The principal thus became part of the Indian political-administrative system, serving as a link between the Spanish authorities and the indigenous population . For a better administration of the aforementioned population, the "pueblos de indios" – where it was reduced to the previously dispersed Aboriginal population -) Luque Talaván, Miguel, ed. (2002). Análisis Histórico-Jurídico de la Nobleza Indiana de Origen Prehispánico (Conferencia en la Escuela "Marqués de Aviles" de Genealogía, Heráldica y Nobiliaria de la "Asociación de Diplomados en Genealogía, Heráldica y Nobiliaria") (pdf) (in Spanish), p. 22.

- Blair, Emma Helen; Robertson, James Alexander, eds. (1903). Relation of the Conquest of the Island of Luzon. The Philippine Islands, 1493–1898. 3. Ohio, Cleveland: Arthur H. Clark Company. p. 145.

- Junker, Laura Lee (1999). Raiding, Trading, and Feasting: The Political Economy of Philippine Chiefdoms. University of Hawaii Press. p. 77. ISBN 978-0-8248-2035-0.

- Rafael, Vicente L. (2005) The Promise of the Foreign: Nationalism and the Technics of Translation in the Spanish Philippines.

- Commission from Sultan of Sulu appointing Baron de Overbeck (an Austrian who was then the Austro-Hungarian Empire's Consul-General in Hong Kong) Dato Bendahara and Rajah of Sandakan. Dated January 22, 1878, The National Archives (United Kingdom).

- Conde de Jolo, List of Spanish Nobility.

- Visconde de Mindanao, List of Spanish Nobility.

- Marques de Camarines, List of Spanish Nobility.

- Sultanate of Sulu

- Welcome to the official website of the Royal House of Sulu

- Historians classify four types of unhispanized societies in the Philippines, some of which still survive in remote and isolated parts of the Country: 1.) Classless societies; 2.) Warrior societies, characterized by a distinct warrior class, in which membership is won by personal achievement, entails privilege, duty and prescribed norms of conduct, and is requisite for community leadership; 3.) Petty Plutocracies, which are dominated socially and politically by a recognized class of rich men who attain membership through birthright, property and the performance of specified ceremonies. They are "petty" because their authority is localized, being extended by neither absentee landlordism nor territorial subjugation; and 4.) Principalities. Although in his book, Scot mentioned mostly examples found in Mindanao, however, this form of society was predominant on ths plains of Visayan Islands, as well as in Luzon, during the pre-conquest era. Cf. William Henry Scott, Cracks in the Parchment Curtain, Quezon City: 1998, p. 139.

- "The Indigenous Peoples Rights Act of 1997." Sec. 2. Declaration of State Policies.- The State shall recognize and promote all the rights of Indigenous Cultural Communities/Indigenous Peoples (ICCs/IPs) hereunder enumerated within the framework of the Constitution: a) The State shall recognize and promote the rights of ICCs/IPs within the framework of national unity and development; b)The State shall protect the rights of ICCs/IPs to their ancestral domains to ensure their economic, social and cultural well being and shall recognize the applicability of customary laws governing property rights or relations in determining the ownership and extent of ancestral domain; c) The State shall recognize, respect and protect the rights of ICCs/IPs to preserve and develop their cultures, traditions and institutions. It shall consider these rights in the formulation of national laws and policies; d) The State shall guarantee that members of the ICCs/IPs regardless of sex, shall equally enjoy the full measure of human rights and freedoms without distinctions or discrimination; e) The State shall take measures, with the participation of the ICCs/IPs concerned, to protect their rights and guarantee respect for their cultural integrity, and to ensure that members of the ICCs/IPs benefit on an equal footing from the rights and opportunities which national laws and regulations grant to other members of the population and f) The State recognizes its obligations to respond to the strong expression of the ICCs/IPs for cultural integrity by assuring maximum ICC/IP participation in the direction of education, health, as well as other services of ICCs/IPs, in order to render such services more responsive to the needs and desires of these communities. Towards these ends, the State shall institute and establish the necessary mechanisms to enforce and guarantee the realization of these rights, taking into consideration their customs, traditions, values, beliefs, their rights to their ancestral domains.......(http://www.chanrobles.com/republicactno8371.htm,

- Cf. Barangay in Enciclopedia Universal Ilustrada Europea-Americana, Madrid: Espasa-Calpe, S. A., 1991, Vol. VII, p.624. The article says: Los nobles de un barangay eran los más ricos ó los más fuertes, formándose por este sistema los dattos ó maguinoos, principes á quienes heredaban los hijos mayores, las hijas á falta de éstos, ó los parientes más próximos si no tenían descendencia directa; pero siempre teniendo en cuenta las condiciones de fuerza ó de dinero...Los vassalos plebeyos tenían que remar en los barcos del maguinoo, cultivar sus campos y pelear en la guerra. Los siervos, que formaban el término medio entre los esclavos y los hombres libres, podían tener propriedad individual, mujer, campos, casa y esclavos; pero los tagalos debían pagar una cantidad en polvo de oro equivalente á una parte de sus cosechas, los de los barangayes bisayas estaban obligados á trabajar en las tieras del señor cinco días al mes, pagarle un tributo anual en arroz y hacerle un presente en las fiestas. Durante la dominación española, el cacique, jefe de un barangay, ejercía funciones judiciales y administrativas. A los tres años tenía el tratamiento de don y se reconocía capacidad para ser gobernadorcillo, con facultades para nombrarse un auxiliar llamado primogenito, siendo hereditario el cargo de jefe. It should also be noted that the more popular and official term used to refer to the leaders of the district or to the cacique during the Spanish period was Cabeza de Barangay.

- Philippine Constitution – Preamble

- “There are not a few judgments, civil and criminal, albeit some very recent, all of which to accept traditional principles re-enunciated not long since. The issue is that of innate nobility—jure sanguinis—that looks into the prerogatives known as jus majestatis and jus honorum, and argues that the holder of such prerogatives is a subject of international law with the logical consequences of that situation. That is to say, a deposed sovereign may legitimately confer titles of nobility, with or without predicates, and the honorifics that pertain to his heraldic patrimony as head of his dynasty. The qualities that render a deposed Sovereign a subject of international law are undeniable, and in fact constitute an absolute personal right the subject may never divest himself of, and that needs no ratification or recognition from any other authority. A reigning Sovereign or Head of State may use the term recognition\ to demonstrate the existence of such a right, but the term is a mere declaration and not a constitutive act”. A notable example of this principle is that of the People's Republic of China, which for a considerable time was not recognized and therefore not admitted to the United Nations, but nonetheless continued to exercise its functions as a sovereign state through both its internal and external organs. “The prerogatives we are examining may be denied and a sovereign state within the limits of its own sphere of influence may prevent the exercise by a deposed Sovereign of his rights in the same way as it may paralyze the use of any right not provided in its own legislation. However such negating action does not go to the existence of such a right and bears only on its exercise. To sum up, therefore, the Italian judiciary, in those cases submitted to its jurisdiction, has confirmed the prerogatives jure sanguinis of a dethroned Sovereign without any vitiation of its effects, whereby in consequence it has explicitly recognized the right to confer titles of nobility and other honorifics relative to his dynastic heraldic patrimony. In particular it has defined the above-mentioned honorifics, among which are those non-national Orders mentioned in Article 7 of the (Italian) Law of the 3rd. March 1951, which prohibits private persons from conferring honors. As to titles of nobility, while their bestowal is legitimate, it must be observed that they receive no protection whatsoever from Italian law, which no longer recognizes statutory nobility, in accordance with the principles enshrined in the Constitution of the Republic. Thus, the concept of the usurpation of a nobiliary title falls outside of Italian legislation.” Cf. Professor Emilio Furno (Advocate in the Italian Supreme Court of Appeal), The Legitimacy of Non-National Orders in Rivista Penale, No.1, January 1961, pp. 46–70.

- Annuario Pontificio 2012 (Libreria Editrice Vaticana 2012 ISBN 978-88-209-8722-0), p. 12.

- Cf. Vatican Council II, Dogmatic Constitution on the Church Lumen gentium, n. 8.

- Also cf. Professor Emilio Furno (Advocate in the Italian Supreme Court of Appeal), The Legitimacy of Non-National Orders in Rivista Penale, No.1, January 1961, pp. 46–70.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on November 5, 2013. Retrieved November 5, 2013.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)