McMurdo Station

The McMurdo Station is a United States Antarctic research station on the south tip of Ross Island, which is in the New Zealand–claimed Ross Dependency on the shore of McMurdo Sound in Antarctica. It is operated by the United States through the United States Antarctic Program, a branch of the National Science Foundation. The station is the largest community in Antarctica, capable of supporting up to 1,258 residents,[2] and serves as one of three year-round United States Antarctic science facilities. All personnel and cargo going to or coming from Amundsen–Scott South Pole Station first pass through McMurdo. By road, McMurdo is 3 kilometres (1.9 mi) from New Zealand's smaller Scott Base.

McMurdo Station | |

|---|---|

McMurdo Station from Observation Hill | |

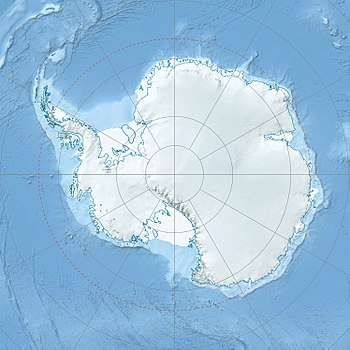

McMurdo Station Location of McMurdo Station in Antarctica | |

| Coordinates: 77°50′47″S 166°40′06″E | |

| Country | |

| Location in Antarctica | Ross Island, Ross Dependency; claimed by New Zealand. |

| Administered by | United States Antarctic Program of the National Science Foundation |

| Established | 16 February 1956 |

| Named for | Archibald McMurdo |

| Elevation | 10 m (30 ft) |

| Population | |

| • Summer | 1,258 |

| • Winter | 250 |

| Time zone | UTC+12 (NZST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+13 (NZDST) |

| Type | All year-round |

| Period | Annual |

| Status | Operational |

| Facilities | More than 85 buildings with facilities that include:[1]

|

| Website | www.nsf.gov |

History

The station takes its name from its geographic location on McMurdo Sound, named after Lieutenant Archibald McMurdo of HMS Terror. Under the command of British explorer James Clark Ross, the Terror first charted the area in 1841. The British explorer Robert Falcon Scott established a base camp close to this spot in 1902 and built a cabin there that was named Discovery Hut. It still stands as a historic monument near the water's edge on Hut Point at McMurdo Station. The volcanic rock of the site is the southernmost bare ground accessible by ship in the world. The United States officially opened its first station at McMurdo on February 16, 1956 as part of Operation Deep Freeze. The base, built by the U.S. Navy Seabees, was initially designated Naval Air Facility McMurdo. On November 28, 1957, Admiral George J. Dufek visited McMurdo with a U.S. congressional delegation for a change-of-command ceremony.[3]

McMurdo Station became the center of scientific and logistical operation during the International Geophysical Year,[3] an international scientific effort that lasted from July 1, 1957, to December 31, 1958. The Antarctic Treaty, subsequently signed by over forty-five governments, regulates intergovernmental relations with respect to Antarctica and governs the conduct of daily life at McMurdo for United States Antarctic Program (USAP) participants. The Antarctic Treaty and related agreements, collectively called the Antarctic Treaty System (ATS), opened for signature on December 1, 1959, and officially entered into force on June 23, 1961.

The first scientific diving protocols were established before 1960 and the first diving operations were documented in November 1961.[4]

Nuclear power 1962–1972

On March 3, 1962, the U.S. Navy activated the PM-3A nuclear power plant at the station. The unit was prefabricated in modules to facilitate transport and assembly. Engineers designed the components to weigh no more than 30,000 pounds (14,000 kg) each and to measure no more than 8 feet 8 inches (2.64 m) by 8 feet 8 inches (2.64 m) by 30 feet (9.1 m). A single core no larger than an oil drum served as the heart of the nuclear reactor. These size and weight restrictions aimed to allow delivery of the reactor in an LC-130 Hercules aircraft. However, the components were actually delivered by ship.[5] The reactor generated 1.8 MW of electrical power[6] and reportedly replaced the need for 1,500 US gallons (5,700 l) of oil daily.[7] Engineers applied the reactor's power, for instance, in producing steam for the salt-water distillation plant. As a result of continuing safety issues (hairline cracks in the reactor and water leaks),[8][9] the U.S. Army Nuclear Power Program decommissioned the plant in 1972.[9] Conventional diesel generators replaced the nuclear power station, with a number of 500 kilowatts (670 hp) diesel generators in a central powerhouse providing electric power. A conventionally-fueled water-desalination plant provided fresh water.

Contemporary functions

As of 2007, McMurdo Station was Antarctica's largest community and a functional, modern-day science station, including a harbor, three airfields[10] (two seasonal), a heliport and more than 100 buildings, including the Albert P. Crary Science and Engineering Center. The station is also home to the continent's two ATMs, both provided by Wells Fargo Bank. The work done at McMurdo Station primarily focuses on science, but most of the residents (approximately 1,000 in the summer and around 250 in the winter) are not scientists, but station personnel who provide support for operations, logistics, information technology, construction, and maintenance.

Scientists and other personnel at McMurdo are participants in the USAP, which co-ordinates research and operational support in the region. Werner Herzog's 2007 documentary Encounters at the End of the World reports on the life and culture of McMurdo Station from the point-of-view of residents. Anthony Powell's 2013 documentary Antarctica: A Year on Ice provides time-lapse photography of Antarctica intertwined with personal accounts from residents of McMurdo Station and of the adjacent Scott Base over the course of a year.

An annual sealift by cargo ships as part of Operation Deep Freeze delivers 8 million U.S. gallons (6.6 million imperial gallons/42 million liters) of fuel and 11 million pounds (5 million kg) of supplies and equipment for McMurdo residents.[11] The ships, operated by the U.S. Military Sealift Command, are manned by civilian mariners. Cargo may range from mail, construction materials, trucks, tractors, dry and frozen food, to scientific instruments. U.S. Coast Guard icebreakers break a ship channel through ice-clogged McMurdo Sound in order for supply ships to reach Winter Quarters Bay at McMurdo. Additional supplies and personnel are flown in to nearby Williams Field from Christchurch in New Zealand.

Between 1962 and 1963, 28 Arcas sounding rockets were launched from McMurdo Station.[12]

McMurdo Station stands about two miles (3 km) from Scott Base, the New Zealand science station, and all of Ross Island lies within a sector claimed by New Zealand. Criticism has been leveled at the base regarding its construction projects, particularly the McMurdo-(Amundsen-Scott) South Pole highway.[13]

McMurdo Station has attempted to improve environmental management and waste removal in order to adhere to the Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty, signed on October 4, 1991, which entered into force on January 14, 1998. This agreement prevents development and provides for the protection of the Antarctic environment through five specific annexes on marine pollution, fauna and flora, environmental impact assessments, waste management, and protected areas. It prohibits all activities relating to mineral resources except scientific. A new waste-treatment facility was built at McMurdo in 2003. Three Enercon E-33 (330 kW each) wind turbines were deployed in 2009 to power McMurdo and New Zealand's Scott Base, reducing diesel consumption by 11% or 463,000 litres per year.[14][15] McMurdo Station (nicknamed "Mac-Town" by its residents) continues to operate as the hub for American activities on the Antarctic continent.

McMurdo Station briefly gained global notice when an anti-war protest took place on February 15, 2003. During the rally, about 50 scientists and station personnel gathered to protest the coming invasion of Iraq by the United States. McMurdo Station was the only Antarctic location to hold such a rally.[16]

Scientific diving operations continue with 10,859 dives having been conducted under the ice from 1989 to 2006. A hyperbaric chamber is available for support of polar diving operations.[4]

Climate

With all months having an average temperature below freezing, McMurdo features a polar ice cap climate (Köppen EF). However, in the warmest months (December and January) the monthly average high temperature may occasionally rise above freezing. The place is protected from cold waves from the interior of Antarctica by the Transantarctic Mountains, so temperatures below −40° are rare, compared to more exposed places like Neumayer Station, which usually gets those temperatures a few times every year, often as early as May, and sometimes even as early as April, and very rarely above 0 °C. The highest temperature ever recorded at McMurdo was 10.8°C on December 21, 1987. There is enough snow melt in summer that a limited amount of vegetation can grow, specifically a few species of moss and lichen.

| Climate data for McMurdo Station (extremes 1956–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 10.2 (50.4) |

5.9 (42.6) |

−1.1 (30.0) |

0.0 (32.0) |

−1.3 (29.7) |

3.3 (37.9) |

−4.4 (24.1) |

−2 (28) |

−3.7 (25.3) |

4.5 (40.1) |

10.0 (50.0) |

10.8 (51.4) |

10.8 (51.4) |

| Average high °C (°F) | −0.6 (30.9) |

−7.3 (18.9) |

−16.2 (2.8) |

−17.3 (0.9) |

−21 (−6) |

−20.4 (−4.7) |

−21.7 (−7.1) |

−22.7 (−8.9) |

−20.8 (−5.4) |

−14.3 (6.3) |

−6.5 (20.3) |

−0.4 (31.3) |

−14.2 (6.4) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −2.8 (27.0) |

−8.8 (16.2) |

−17.3 (0.9) |

−20.9 (−5.6) |

−23.3 (−9.9) |

−22.9 (−9.2) |

−25.8 (−14.4) |

−27.4 (−17.3) |

−25.7 (−14.3) |

−19.4 (−2.9) |

−9.7 (14.5) |

−3.5 (25.7) |

−17.3 (0.9) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −4.6 (23.7) |

−11.4 (11.5) |

−21.3 (−6.3) |

−23.4 (−10.1) |

−26.5 (−15.7) |

−26.8 (−16.2) |

−28.4 (−19.1) |

−29.5 (−21.1) |

−27.5 (−17.5) |

−19.8 (−3.6) |

−10.9 (12.4) |

−4.4 (24.1) |

−19.7 (−3.5) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −22.1 (−7.8) |

−25 (−13) |

−43.3 (−45.9) |

−41.9 (−43.4) |

−44.8 (−48.6) |

−43.9 (−47.0) |

−50.6 (−59.1) |

−49.4 (−56.9) |

−45.1 (−49.2) |

−40 (−40) |

−28.5 (−19.3) |

−18 (0) |

−50.6 (−59.1) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 16 (0.6) |

29 (1.1) |

15 (0.6) |

18 (0.7) |

21 (0.8) |

28 (1.1) |

17 (0.7) |

13 (0.5) |

10 (0.4) |

20 (0.8) |

12 (0.5) |

14 (0.6) |

213 (8.4) |

| Average snowfall cm (inches) | 6.6 (2.6) |

22.4 (8.8) |

11.4 (4.5) |

12.7 (5.0) |

17.0 (6.7) |

17.8 (7.0) |

14.0 (5.5) |

6.6 (2.6) |

7.6 (3.0) |

13.5 (5.3) |

8.4 (3.3) |

10.4 (4.1) |

148.4 (58.4) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 2.6 | 4.7 | 3.2 | 4.5 | 5.5 | 5.7 | 4.7 | 4.1 | 3.0 | 3.2 | 2.4 | 2.5 | 46.1 |

| Average snowy days | 12.8 | 17.6 | 17.8 | 16.4 | 16.2 | 15.6 | 15.3 | 14.5 | 13.3 | 14.5 | 13.5 | 13.8 | 181.3 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 66.7 | 65.2 | 66.6 | 66.6 | 64.2 | 62.4 | 60.2 | 63.4 | 55.8 | 61.4 | 64.7 | 67.0 | 63.7 |

| Source 1: Deutscher Wetterdienst (average temperatures)[17] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: NOAA (precipitation, snowy days, and humidity data 1961–1986),[18] Meteo Climat (record highs and lows)[19] | |||||||||||||

Communications

For a time, McMurdo had Antarctica's only television station, AFAN-TV, running vintage programs provided by the military. The station's equipment was susceptible to "electronic burping" from the diesel generators that provide electricity in the outpost. The station was profiled in a 1974 article in TV Guide magazine. Now, McMurdo receives three channels of the US Military's American Forces Network, the Australia Network, and New Zealand news broadcasts. Television broadcasts are received by satellite at Black Island, and transmitted 25 miles (40 km) by digital microwave to McMurdo. Also, for a time McMurdo also played host to one of the only two shortwave broadcast stations in Antarctica. The station—AFAN McMurdo—transmitted with a power of 1 kilowatt on the shortwave frequency of 6,012 kHz and became a target for shortwave radio listening hobbyists around the world because of its rarity. The station continued broadcasting on shortwave into the 1980s when it dropped shortwave while continuing FM transmission.[20]

McMurdo Station receives both Internet and voice communications by satellite communications via the Optus D1 satellite and relayed to Sydney, Australia.[21][22] A satellite dish at Black Island provides 20 Mbit/s Internet connectivity and voice communications. Voice communications are tied into the United States Antarctic Program headquarters in Centennial, Colorado, providing inbound and outbound calls to McMurdo from the US. Voice communications within station are conducted via VHF radio.

Transportation

Surface

McMurdo has the world's most southerly harbor. A multitude of on- and off-road vehicles transport people and cargo around the station area, including Ivan the Terra Bus. There is a road from McMurdo to the New Zealand Scott Base and South Pole, the South Pole Traverse.

Air

McMurdo is serviced seasonally by three airports:

- Phoenix Airfield (ICAO: NZFX), a compacted snow runway which replaced Pegasus Field (ICAO: NZPG) in 2017

- Sea Ice Runway (ICAO: NZIR), an annual runway constructed on the sea ice nearest McMurdo Station

- Williams Field (ICAO: NZWD), a permanent snow runway

Historic sites

The Richard E. Byrd Historic Monument was erected at McMurdo in 1965. It comprises a bronze bust on black marble, 150 cm × 60 cm (5 ft × 2 ft) square, on a wooden platform, bearing inscriptions describing the polar exploration achievements of Richard E. Byrd. It has been designated a Historic Site or Monument (HSM 54), following a proposal by the United States to the Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meeting.[23]

The bronze Nuclear Power Plant Plaque is about 45 cm × 60 cm (18 in × 24 in) in size, and is secured to a large vertical rock halfway up the west side of Observation Hill, at the former site of the PM-3A nuclear power reactor at McMurdo Station. The inscription details the achievements of Antarctica's first nuclear power plant. It has been designated a Historic Site or Monument (HSM 85), following a proposal by the United States to the Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meeting.[23]

Points of interest

Facilities at the station include:

- Albert P. Crary Science and Engineering Center (CSEC)

- Chapel of the Snows Interdenominational Chapel

- Observation Hill

- Discovery Hut, built during Scott's 1901–1903 expedition

- Williams Field airport

- Memorial plaque to three airmen killed in 1946 while surveying the territory

- Ross Island Disc Golf Course[24]

See also

- Air New Zealand Flight 901

- Amundsen–Scott South Pole Station

- ANDRILL

- List of Antarctic field camps

- The Antarctic Sun

- Byrd Station

- Castle Rock

- Chapel of the Snows

- Crime in Antarctica

- Ellsworth Station

- Erebus crystal

- First women to fly to Antarctica

- Hallett Station

- List of Antarctic expeditions

- Little America V

- Marble Point

- McMurdo Sound

- Mount Erebus

- Palmer Station

- Plateau Station

- List of Antarctic research stations

- Ross Ice Shelf

- Scott Base

- Siple Station

- Williams Field

Notes

- "McMurdo Station". Giosciences: Polar Programs. National Science Foundation. Retrieved July 11, 2016.

- "4.0 Antarctica - Past and Present". National Science Foundation.

- "US Antarctic Base Has Busy Day". Spartanburg Herald-Journal. November 29, 1957. Retrieved July 7, 2010.

- Pollock, Neal W. (2007). "Scientific diving in Antarctica: history and current practice". Diving and Hyperbaric Medicine. 37: 204–11. Retrieved June 8, 2013.

- Rejcek, Peter (June 25, 2010). "Powerful reminder: Plaque dedicated to former McMurdo nuclear plant marks significant moment in Antarctic history". The Antarctic Sun. Retrieved June 16, 2012.

- Priestly, Rebecca (January 7, 2012). "The wind turbines of Scott Base". The New Zealand Listener. Retrieved June 16, 2012.

- Clarke, Peter McFerrin (1966). On the ice. Burdette.

- "Nuclear Science Abstracts". August 1967.

- "Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists". Educational Foundation for Nuclear Science. October 1978.

- Miguel Llanos (January 25, 2007). "Reflections from time on 'the Ice'". NBC News. Retrieved January 11, 2008.

- Modern Marvels: Sub-Zero. The History Channel.

- "McMurdo Station". Astronautix.com. Archived from the original on October 6, 2012. Retrieved August 13, 2012.

- Moss, Stephen (January 24, 2003). "No, not a ski resort – it's the south pole". The Guardian. London. Retrieved May 12, 2010.

- "Ross Island Wind Energy". Antarcticanz.govt.nz. Retrieved September 28, 2015.

- "New Zealand Wind Energy Association". Windenergy.org.nz. Archived from the original on November 17, 2013. Retrieved November 6, 2013.

- "Protest photos". PunchDown. Archived from the original on October 25, 2010. Retrieved August 29, 2010.

- "Klimatafel von McMurdo (USA) / Antarktis" (PDF). Baseline climate means (1961–1990) from stations all over the world (in German). Deutscher Wetterdienst. Retrieved April 6, 2017.

- "McMurdo Sound Climate Normals 1961−1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved February 19, 2014.

- "Station McMurdo" (in French). Meteo Climat. Retrieved April 6, 2017.

- Berg, Jerome S. Broadcasting on the Short Waves, 1945 to Today. p. 213 – via Google Books.

- "Optus D1 satellite to provide critical link to Antarctica and to help monitor our changing Earth. " (September 20, 2007). Retrieved 2013-08-06

- Wolejsza, C.; Whiteley, D.; Paciaroni, J. (2010). “McMurdo Communications Architecture for Polar Environmental Satellite Data Retrieval.” Retrieved 2013-08-06

- "List of Historic Sites and Monuments approved by the ATCM (2012)" (PDF). Antarctic Treaty Secretariat. 2012. Retrieved January 3, 2014.

- "Ross Island DGC". DGCourseReview. Retrieved September 3, 2013.

References

- Clarke, Peter: On the Ice. Rand McNally & Company, 1966

- "Facts About the United States Antarctic Research Program". Division of Polar Programs, National Science Foundation; July 1982.

- United States Antarctic Research Program Calendar 1983

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to McMurdo Station. |

- "McMurdo Station". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey.

- National Science Foundation page about McMurdo Station

- Virtual Tour – McMurdo Station Antarctica

- Life and work at McMurdo Station – from USA Today

- Information (including flight records) about NASA's balloon launches at Williams Field

- Big Dead Place (life, culture, and satire of Antarctic residency)

- Usap McMurdo Station webcam

- High resolution GigaPan picture of McMurdo station

- Antarctica's Library at McMurdo Station

.svg.png)