Elisha Kent Kane

Elisha Kent Kane (February 3, 1820 – February 16, 1857) was an American explorer, and a medical officer in the United States Navy during the first half of the 19th century. He was a member of two Arctic expeditions to rescue the explorer Sir John Franklin.

Elisha Kent Kane | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | February 3, 1820 Philadelphia, Pennsylvania |

| Died | February 16, 1857 (aged 37) Havana, Cuba |

| Buried | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch | United States Navy |

| Service years | 1843–1857 |

| Rank | Assistant surgeon |

| Expeditions | |

| Relations |

|

He was present at the discovery of Franklin's first winter camp, but he did not find out what had happened to the fatal expedition.

Early life

Born in Philadelphia, Kane was the son of John Kintzing Kane, a U.S. district judge, and Jane Duval Leiper. His maternal grandfather was Thomas Leiper, American Revolutionary War patriot and a founder of the Philadelphia City Troop.

His brother was attorney, diplomat, abolitionist, and Civil War general, Thomas L. Kane. Kane graduated from the University of Pennsylvania Medical School in 1842.

Career

On September 14, 1843, he became an assistant surgeon in the Navy. He served in the China Commercial Treaty mission under Caleb Cushing, in the Africa Squadron,[1] and in the United States Marine Corps during the Mexican–American War. One battle that Kane fought in was at Nopalucan on January 6, 1848. At Nopalucan, he captured, befriended, and saved the life of Mexican General Antonio Gaona and the general's wounded son.[2]

Kane was appointed senior medical officer of the Grinnell Arctic expedition of 1850–1851 under the command of Edwin de Haven, which searched unsuccessfully for Sir John Franklin's lost expedition.[3] During this expedition, the crew discovered Franklin's first winter camp.

In 1852, Kane met the Fox sisters, famous for their spirit rapping séances, and he became enamored with the middle sister, Margaret. Kane was convinced that the sisters were frauds, and sought to reform Margaret. She would later claim that they were secretly married in 1856—she changed her name to Margaret Fox Kane—and engaged the family in lawsuits over his will. After Kane's death, Margaret converted to the Roman Catholic faith, but would eventually return to spiritualism.[4][1]

Kane then organized and headed the Second Grinnell expedition which sailed from New York on May 31, 1853, and wintered in Rensselaer Bay. Though suffering from scurvy, and at times near death, he pushed on and charted the coasts of Smith Sound and the Kane Basin, penetrating farther north than any other explorer had done up to that time. At Cape Constitution he discovered the ice-free Kennedy Channel, later followed by Isaac Israel Hayes, Charles Francis Hall, Augustus Greely, and Robert E. Peary in turn as they drove toward the North Pole.[5]

Kane finally abandoned the icebound brig Advance on May 20, 1855, and made an 83-day march of indomitable courage to Upernavik. The party, carrying the invalids, lost only one man. Kane and his men were saved by a sailing ship. Kane returned to New York on October 11, 1855, and the following year published his two-volume Arctic Explorations.[5]

Death

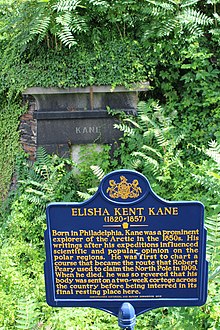

After visiting England to fulfill his promise to deliver his report personally to Lady Jane Franklin, he sailed to Havana in a vain attempt to recover his health, after being advised to do so by his doctor. He died there on February 16, 1857.[5] His body was brought to New Orleans and carried by steamboat and a funeral train to Philadelphia; the train was met at nearly every platform by a memorial delegation, and is said to have been the longest funeral train of the century, surpassed only by that of Abraham Lincoln. After lying in state at Independence Hall, he was transported to Philadelphia's Laurel Hill Cemetery where he was placed in the family vault on the hillside near what is now Kelly Drive.

Legacy

Kane received medals from Congress, the Royal Geographical Society, and the Société de géographie. The Geographical Society of Philadelphia created the Elisha Kent Kane Medal in his honor. He was also elected to the American Antiquarian Society in 1855.[6]

The Anoatok historic manor at Kane, Pennsylvania, was named to allude to his Arctic adventures. The destroyer USS Kane (DD-235) was named for him, as was a later oceanographic research ship, the USNS Kane (T-AGS-27). A lunar crater, Kane, was also named for him. In 1986, the U.S. Postal Service issued a 22 cent postage stamp in his honor, depicting his route to the Arctic.[7]

Publications

- The United States Grinnell Expedition in Search of Sir John Franklin: A personal narrative; Philadelphia: Childs & Peterson, 1856, at the Making of America Project.

- Arctic explorations: The second Grinnell expedition in search of Sir John Franklin, 1853,54,55; Philadelphia: Childs & Peterson, 1857, at the Making of America Project.

References

Footnotes

- "Kane Elisha Kent". Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online. Retrieved January 21, 2012.

- Joe Musso, Kane Knife October 28, 2004

- "The U.S. Grinnell Expedition in Search of Sir John Franklin: a Personal Narrative". World Digital Library. 1854. Retrieved October 2, 2013.

- Doyle 1926: volume 1, 89–94

- Chisholm 1911.

- American Antiquarian Society Members Directory

- Scott catalog # 2220.

Further reading

- The Royal Navy in Polar Exploration from Franklin to Scott, E C Coleman 2006 (Tempus Publishing)

- Corner, George W. Doctor Kane of the Arctic Seas (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1972)

- Edinger, Ray. Love and Ice: The Tragic Obsessions of Dr. Elisha Kent Kane, Arctic Explorer (Savannah, Frederic C. Beil, Publisher. 2015). ISBN 978-1-929490-42-4

- Elder, William, Biography of Elisha Kent Kane (Philadelphia, 1858)

- Fox, Margaret. Love Life of Dr. Kane (New York, 1866)

- Greely, A.W., American Explorers and Travelers (New York, 1894)

- McGoogan, Ken, Race to the Polar Sea: The Heroic Adventures and Romantic Obsessions of Elisha Kent Kane (Toronto, HarperCollins Publishers Ltd, 2008. ISBN 978-0-00-200776-4)

- Mirsky, Jeanette. Elisha Kent Kane and the Seafaring Frontier (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1954)

- Robinson, Michael, The Coldest Crucible: Arctic Exploration and American Culture (Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 2006)

- Sawin, Mark. Raising Kane: Elisha Kent Kane and the Culture of Fame in Antebellum America. Philadelphia: The American Philosophical Society Press, 2009. ISBN 1-60618-983-2

- Sonntag, August (1865). Professor Sonntag's Thrilling Narrative Of The Grinnell Exploring Expedition To The Arctic Ocean In The Years 1853, 1854, and 1855 In Search of Sir John Franklin, Under The Command of Dr. E. K. Kane, U.S.N. Philadelphia: Jas. T. Lloyd & Co. Retrieved August 15, 2009.

- David Chapin, Exploring Other Worlds (University of Massachusetts Press, 2004).

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Elisha Kent Kane. |

- Works by Elisha Kent Kane at Biodiversity Heritage Library

- Works by Elisha Kent Kane at Open Library

- Works by Elisha Kent Kane at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Elisha Kent Kane at Internet Archive

- Works by or about Elisha Kent Kane in libraries (WorldCat catalog)

- The Papers of James Laws at Dartmouth College Library

- The Papers of Margaret Elder Dow at Dartmouth College Library

This article incorporates text from the public domain Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships.