Far Eastern Party

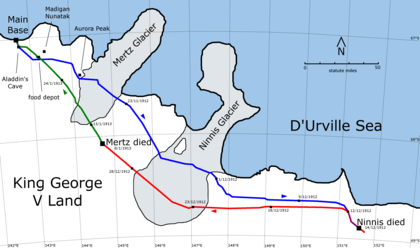

The Far Eastern Party was a sledging component of the 1911–1914 Australasian Antarctic expedition, which investigated the previously unexplored coastal regions of Antarctica west of Cape Adare. Led by Douglas Mawson, the party aimed to explore the area far to the east of their main base in Adélie Land, pushing about 500 miles (800 km) towards Victoria Land. Accompanying Mawson were Belgrave Edward Ninnis, a lieutenant in the Royal Fusiliers, and Swiss ski expert Xavier Mertz; the party used sledge dogs to increase their speed across the ice. Initially they made good progress, crossing two huge glaciers on their route south-east.

On 14 December 1912, with the party more than 311 miles (501 km) from the safety of the main base at Cape Denison, Ninnis and the sledge he was walking beside broke through the snow lid of a crevasse and were lost. Their supplies now severely compromised, Mawson and Mertz turned back west, gradually shooting the remaining sledge dogs for food to supplement their scarce rations. As they crossed the first glacier on their return journey Mertz became sick, making progress difficult. After almost a week of making very little headway Mertz died, leaving Mawson to carry on alone.

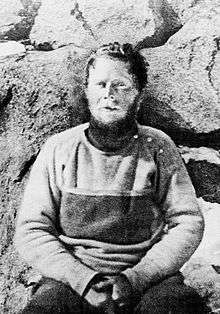

For almost a month he pulled his sledge across the Antarctic, crossing the second glacier, despite an illness that increasingly weakened him. Mawson reached the comparative safety of Aladdin's Cave—a food depot five point five miles (8.9 km) from the main base—on 1 February 1913, only to be trapped there for a week while a blizzard raged outside. As a result, he missed the ship back to Australia; the SY Aurora had sailed on 8 February, just hours before his return to Cape Denison, after waiting for more than three weeks. With a relief party, Mawson remained at Cape Denison until the Aurora returned the following summer in December 1913.

The causes of Mertz's death and Mawson's related illness remain uncertain; a 1969 study suggested hypervitaminosis A, presumably caused by the men eating the livers of their Greenland huskies, which are now known to be unusually high in vitamin A. While this is considered the most likely theory, dissenting opinions suggest prolonged cold exposure or psychological stresses. In 1976 explorer and mountaineer Sir Edmund Hillary described Mawson's month-long journey as "probably the greatest story of lone survival in Polar exploration".[1]

Background

The Australasian Antarctic expedition, commanded by Douglas Mawson, explored part of East Antarctica between 1911 and 1914. The expedition's main base was established in January 1912, at Cape Denison in Commonwealth Bay, Adélie Land.[2] This was much farther west than originally intended; dense pack ice had prevented the expedition ship SY Aurora from landing closer to Cape Adare, the original eastern limit.[3] Only after the Aurora—heading west—had rounded the ice tongue of the Mertz Glacier, was a landing made.[2][nb 1]

Battling katabatic winds that swept down from the Antarctic Plateau, the shore party erected their hut and began preparations for the following summer's sledging expeditions.[2] The men readied clothing, sledges, tents and rations,[nb 2] conducted limited survey parties, and deployed several caches of supplies.[5][6] The most notable of these depots was Aladdin's Cave, excavated from the ice on the slope five and a half miles (9 km) to the south of the main hut.[7]

On 27 October 1912, Mawson outlined the summer sledging program.[8] Of the seven sledging parties that would depart from Cape Denison, three would head east. The Eastern Coastal Party, led by the geologist Cecil Madigan, was charged with exploring beyond the Mertz Glacier tongue;[9] they would initially be supported by the Near Eastern Party led by Frank Leslie Stillwell, which would then turn to mapping the area between Cape Denison and the glacier.[10]

The final party, led by Mawson, would push rapidly inland to the south of the Coastal Party towards Victoria Land, an area he had explored during Ernest Shackleton's Nimrod Expedition in 1908–1909. He hoped to travel about 500 miles (800 km) east, collecting geological data and specimens, mapping the coast, and claiming territory for the crown.[11]

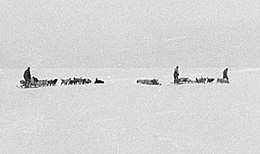

Assisting him on this Far Eastern Party was Belgrave Edward Ninnis, a lieutenant in the Royal Fusiliers, and the Swiss ski expert Xavier Mertz.[11][12] They were in charge of the expedition's Greenland huskies, who would be crucial if the party was to cover the distance at the speed Mawson intended. Ninnis and Mertz had spent the winter preparing the dogs for the journey, sewing harnesses and teaching them to run in teams with the sledges.[nb 3][14][15] Each of the parties was required to return to Cape Denison by 15 January 1913, to allow time for the Aurora to collect them and escape Antarctic waters unencumbered by the winter sea ice.[16]

Journey eastwards

Blizzards prevented the parties from leaving Cape Denison until 10 November 1912, four days after the scheduled start date. In his diary, Mertz recorded the clearing weather as "definitely a good omen".[17] Mawson wrote a short letter to his fiancée, Paquita Delprat: "The weather is fine this morning though the wind still blows. We shall get away in an hour's time. I have two good companions, Dr Mertz and Lieut. Ninnis. It is unlikely that any harm will happen to us, but should I not return to you in Australia, please know that I truly loved you. I must be closing now as the others are waiting."[17]

Allowing Madigan and Stillwell's parties a head-start, Mawson, Ninnis, Mertz and the seventeen dogs left Cape Denison early in the afternoon, reaching Aladdin's Cave four hours later.[18][19] Stopping for the night, they took on extra supplies and rearranged the sledges. The first team of dogs would haul a train of two sledges, which collectively carried half the weight of the party's supplies. The remaining supplies were put on the third sledge, towed by the second dog team.[nb 4][19]

Heading south the following day to avoid crevasses to the east, they travelled about eight miles (13 km) before poor weather forced them to stop and camp. Strong winds confined them to the tent until 13 November, and they were able to travel just a short distance before the weather picked up again. For three more days they remained in their tent, unable even to light the stove.[21] When the weather cleared on 16 November, Madigan and Stillwell's parties joined them.[22] The three parties travelled together for much of the following day, before Mawson's party separated and pushed on ahead in the late afternoon.[23]

Mertz and Ninnis Glaciers

Heading south-east towards the Mertz Glacier, with Mertz skiing ahead and Mawson and Ninnis driving the dogs, the party covered 15 miles (24 km) on 18 November.[24] This was despite encountering sastrugi—ridges in the ice caused by wind—as high as three feet (91 cm), that caused the dogs to slip and the sledges to roll.[25][26] During the day they passed two peaks, which Mawson named Madigan Nunatak and Aurora Peak, after the leader of the Eastern Coastal Party and the expedition's ship.[27] The following day they began the steep descent to the Mertz Glacier. After the sledges several times overtook the dogs, the huskies were allowed to run free down the slope.[28]

Following a particularly steep descent the following day, half of Mawson's team of dogs—reattached to his sledges—were almost lost when they fell into a crevasse. They were hauled out, but Mawson decided to camp when one of the dogs, Ginger Bitch, gave birth to the first in a litter of 14 pups.[nb 5][31]

Over the next several days, the party continued across the glacier. They developed a method of crossing the many crevasses; the forerunner, on skis, would cross the snow covering the hole—the lid—and once across the first of the two dog teams would follow. Only after the first dog team was across would the second follow, "otherwise", wrote Mawson, "the dogs in the rear would make a course direct for wherever the front dogs happened to be, cutting across corners and probably dragging their sledge sideways into a crevasse".[32] But despite their precautions Ninnis fell down and was rescued from three crevasses, once when they found they had pitched their tent on its lip.[33]

After Mawson slipped into a crevasse, they began to tie themselves to their sledges as a precaution.[34] Ninnis developed photokeratitis (snow-blindness), which Mawson treated with zinc sulfate and cocaine hydrochloride.[35] They were also losing dogs; one broke his leg and was shot, another fell ill, and a third was lost down a crevasse.[36] On 24 November, the party reached the eastern side of the glacier and ascended to the plateau.[37]

On level ground again, they began to make quick progress. They awoke on the morning of 27 November to find another glacier (later known as the Ninnis Glacier) far larger than the first.[38][39] As with the first glacier, they had to unhitch the dogs from the sledges and slowly make the treacherous descent. Once at the bottom of the glacier they spent four days crossing fields of crevasses, battling strong winds and poor light that made navigation difficult.[40]

In the harsh conditions, the dogs began to grow restless; one of them, Shackleton, tore open the men's food bag and devoured a 2.5-pound (1.1 kg) pack of butter, crucial for their nourishment to supplement the hoosh.[41] On 30 November, the party reached the eastern limit of the glacier and began the ascent to the plateau beyond, only to find themselves confronted at the top by sastrugi so sharp-edged the dogs were useless.[42] Worse still, temperatures rose to 1 °C (34 °F), melting the snow and making pulling difficult; the party switched to travelling at night to avoid the worst of the conditions.[43]

From atop the ridge on the eastern side of the Ninnis Glacier, Mawson began to doubt the accuracy of the reports of land to the east by Charles Wilkes during the 1838–1842 United States Exploring Expedition.[43] By Wilkes' reckoning, Mawson recorded in his diary, "We now appear to be off the real continent edge."[44] Concerned about overlap with Madigan's party to the north, he turned his party south. They made good progress initially, but beginning on 6 December a blizzard confined them to their tent for three days.[43] On 9 December, they set off again, but Ninnis was struggling. He had developed neuralgia on the left side of his face and a whitlow on one of his fingers. The latter was making sleep difficult for him, and, on 13 December, Mawson lanced the finger.[45]

Death of Ninnis

On the evening of 13 December Mawson and Mertz rearranged the sledges. The rear-most sledge, which had carried the most weight, was well-worn, and they decided to abandon it. The remaining supplies were re-distributed between the remaining two sledges. Most of the important supplies—the tent and most of the food—were stored on the new rear sledge;[47] if they were to lose a sledge down a crevasse, they reasoned, it would be the front, less-vital sledge.[48] As the rear sledge was heavier, the strongest of remaining dogs were assigned to pull it.[47] At the camp they left a small amount of supplies, including the abandoned sledge and a tent cover, without the floor or poles.[49]

By noon the next day they had covered 311 miles (501 km) from the Cape Denison hut.[30] Mertz was ahead on skis, breaking trail. Mawson sat on the first sledge; Ninnis walked beside the second.[49] In his diary that night, Mertz recounted: "Around 1 pm, I crossed a crevasse, similar to the hundred previous ones we had passed during the last weeks. I cried out "crevasse!", moved at right angle, and went forward. Around five minutes later, I looked behind. Mawson was following, looking at his sledge in front of him. I couldn't see Ninnis, so I stopped to have a better look. Mawson turned round to know the reason I was looking behind me. He immediately jumped out of his sledge, and rushed back. When he nodded his head, I followed him, driving back his sledge."[46]

Ninnis, his sledge and dog team had fallen through a crevasse 11 feet (3.4 m) wide with straight, ice walls.[50] On a ledge deep in the hole, Mawson and Mertz could see the bodies of two dogs—one still alive, but seriously injured—and the remains of Ninnis' sledge. There was no sign of their companion.[51] They measured the distance to the ledge as 150 feet (46 m), too far for their ropes to reach.[52] "Dog ceased to moan shortly", wrote Mawson in his diary that night. "We called and sounded for three hours, then went a few miles to a hill and took position observations. Came back, called & sounded for an hour. Read the burial service."[50]

Return

Along with the heavy-weather tent, most of their own food and all of the dogs' food, they had lost the pickaxe, the shovel, and Mertz's waterproof overpants and helmet. On Mawson's sledge they had their stove, fuel, sleeping bags, and ten days' worth of food.[49][53] Their best immediate hope was to reach the camp of two days earlier where they had left the abandoned sledge and supplies, 15 miles (24 km) west. They reached it in five-and-a-half-hours, where Mertz used the tent cover, with the runners from the abandoned sledge and a ski as poles, to erect a shelter.[54]

They were faced with two possible routes back to Cape Denison. The first option was to make for the coast, where they could supplement their meagre supplies with seal meat, and hope to meet with Madigan's party; that would considerably lengthen the journey, and the sea ice in summer could not be relied on. Or, pushing slightly to the south of their outward route, they could hope to avoid the worst of the crevasses and aim for speed.[55] Mawson chose the inland route, which meant that in the absence of fresh seal meat they would have to resort to eating their remaining dogs.[56] The first dog—George—was killed the following morning, and of his meat some was fried for the men and the rest fed to the now starving dogs. "On the whole it was voted good" wrote Mawson of the meat, "though it had a strong, musty taste and was so stringy that it could not be properly chewed".[57]

Before setting off again they raised the flag—which they had forgotten to do at their furthest point—and claimed the land for the crown.[56] With the temperature rising, they switched to travelling at night to take advantage of the harder surface the cold provided.[57] With the five remaining dogs, Mawson and Mertz pushed on. Starving, the dogs began to struggle; two more—Johnson and Mary—were shot and divided between men and dogs over the following days.[58] Mawson and Mertz found most of the meat tough, but enjoyed the liver; it, at least, was tender.[53] With the pulling power of the dogs now severely depleted, Mertz stopped making trail and instead helped Mawson to pull the sledge. Despite the challenges, they made good progress; in the first four nights they travelled 60 miles (97 km).[59] As they approached the Ninnis Glacier on 21 December, Haldane—once the largest and strongest of the dogs—was shot.[60][61]

Death of Mertz

Both men were suffering, but Mertz in particular started to feel ill. He complained of stomach pains, and this began to slow them down.[62] Pavlova was killed, leaving only one remaining dog. Mawson decided to lighten their sledge, and much of the equipment—including the camera, photographic films, and all of the scientific equipment save the theodolite—was abandoned.[63] On 29 December, the day they cleared the Ninnis Glacier, the last dog was killed. Mawson recorded: "Had a great breakfast off Ginger's skull—thyroids and brain".[64][65] Two days later Mawson recorded that Mertz was "off colour"; Mertz wrote that he was "really tired [and] shall write no more".[nb 6][66][67]

They made 5 miles (8.0 km) on 31 December, no progress for the following two days, and 5 miles more on 3 January. "[The] cold wind frost-bit Mertz's fingers" recorded Mawson, "and he is generally in a very bad condition. Skin coming off legs, etc—so had to camp though going was good."[67] Not until 6 January did they make any more progress; they went 2 miles (3.2 km) before Mertz collapsed.[68] The following day Mawson placed Mertz onto the sledge in his sleeping bag and continued, but was forced to stop and camp when Mertz's condition again deteriorated. Mawson recorded: "He is very weak, becomes more and more delirious, rarely being able to speak coherently. He will eat or drink nothing. At 8 pm he raves & breaks a tent pole. Continues to rave & call 'Oh Veh, Oh Veh' [O weh!, 'Oh dear!'] for hours. I hold him down, then he becomes more peaceful & I put him quietly in the bag. He dies peacefully at about 2 am on morning of 8th."[69][70]

Strong winds prevented Mawson from continuing for two days. Instead, he prepared for travelling alone, removing the rearmost half from the sledge, and rearranging its cargo. To save having to carry excess kerosene for the stove, he boiled the remainder of the dog meat. Dragging Mertz's body in the sleeping bag from the tent, Mawson constructed a rough cairn from snow blocks to cover it, and used two spare beams from the sledge to form a cross, which he placed on the top. The following day he read the burial service.[71]

Alone

As the weather cleared on 11 January, Mawson continued west, estimating the distance back to Cape Denison at 100 miles (160 km).[69][72] He travelled two miles (3.2 km) before pain in his feet forced him to stop; he found that the soles of his feet had separated as a complete layer. Applying lanolin to his feet and wrapping them in several pairs of socks under his boots, he continued.[73] "My whole body is apparently rotting from lack of nourishment" he recorded, "frost-bitten fingertips festering, mucous membrane of nose gone, saliva glands of mouth refusing duty, skin coming off whole body".[74] Averaging around five miles (8.0 km) a day, he began to cross the Mertz Glacier.

On 17 January, he broke through the lid of a crevasse, but the rope around his waist held him to the sledge and halted his fall.[75] "I had time to say to myself "So this is the end" [Mawson recorded], expecting every moment the sledge to crash on my head and both of us to go to the bottom unseen below. Then I thought of the food left uneaten in the sledge—and, as the sledge stopped without coming down, I thought of Providence again giving me a chance. The chance looked very small as the rope had sawed into the overhanging lid, my finger ends all damaged, myself weak ... With the feeling that Providence was helping me I made a great struggle, half getting out, then slipping back again several times, but at last just did it. Then I felt grateful to Providence ... who has so many times already helped me."[76][77]

To save himself from future crevasses, Mawson constructed a rope ladder, which he carried over his shoulder and was attached to the sledge. It paid off almost immediately, and twice in the following days it allowed him to climb from crevasses.[78] Once out of the Mertz Glacier his mileage increased, and on 28 January, Madigan Nunatak came into view. The following day, after travelling five miles (8.0 km), a cairn covered with black cloth appeared about 300 yards (270 m) to his right. In it he found food and a note from Archibald Lang McLean, who along with Frank Hurley and Alfred Hodgeman had been sent out by Aurora's captain, John King Davis, to search for the Far Eastern Party.[79][80]

From the note, Mawson learned he was 21 miles (34 km) south-east of Aladdin's Cave, and near two further food depots. The note also reported on the other parties of the expedition—all had returned to the hut safely—and on Roald Amundsen's attainment of the South Pole in December 1911.[79] The cairn had been left there just six hours before, when the three men had returned to the hut.[81] Struggling on his injured feet and lacking crampons—he had thrown his away after he crossed the Mertz Glacier—Mawson took three days to reach Aladdin's Cave.[79][82]

Although supplies had been left in Aladdin's Cave—including fresh fruit—there were not the spare crampons he had expected. Without them he could not hope to descend the steep ice slope to the hut, and so he began to fashion his own, collecting nails from every available source and hammering them into wood from spare packing cases.[83][84] Even when completed, a blizzard confined him to the cave, and only on 8 February was he able to begin the descent. Nearing the hut, he was spotted by three men working outside, who rushed up the hill to meet him.[85]

Aftermath

The Aurora arrived at Cape Denison on 13 January 1913. When Mawson's party failed to return, Davis sailed her east along the coast as far as the Mertz Glacier tongue, searching for the party. Finding no sign and reaching the end of the navigable ice-free water, they returned to Cape Denison. The oncoming winter concerned Davis, and on 8 February—just hours before Mawson's return to the hut—the ship departed Commonwealth Bay, leaving six men behind as a relief party. Upon Mawson's return, the Aurora was recalled by wireless radio, but powerful katabatic winds sweeping down from the plateau prevented the ship's boat from reaching the shore to collect the men.[86]

The Aurora returned to Cape Denison the following summer, in mid-December, to take the men home.[87] The delay may have saved Mawson's life; he later told Phillip Law, then-director of Australian National Antarctic Research Expeditions, that he did not believe he could have survived the sea journey so soon after his ordeal.[88]

The cause of Mawson and Mertz's illnesses remains in part a mystery. At the time, McLean—the expedition's chief surgeon and one of the men who had remained at Cape Denison—attributed their sickness to colitis; Mawson wrote in The Home of the Blizzard, his official account of the expedition, that Mertz died of fever and appendicitis.[89][90] A 1969 study by Sir John Cleland and R. V. Southcott of the University of Adelaide concluded that the symptoms Mawson described—hair, skin and weight loss, depression, dysentery and persistent skin infections—indicated the men had suffered hypervitaminosis A, an excessive intake of vitamin A. This is found in unusually high quantities in the livers of Greenland Huskies, of which both Mertz and Mawson consumed large amounts.[90]

While hypervitaminosis A is the generally accepted medical diagnosis for Mertz's death and Mawson's illness, the theory has its detractors.[91] Law believed it was "completely unproven ... The symptoms that were described are exactly the ones you get from cold exposure. You don't have to predicate a theory of this sort to explain the soles coming off your feet."[92] A 2005 article in The Medical Journal of Australia by Denise Carrington-Smith suggested it may have been "the psychological stresses related to the death of a close friend and the deaths of the dogs he had cared for", and a switch from a predominately vegetarian diet that killed Mertz, not hypervitaminosis A.[93]

Suggestions of cannibalism—that Mawson may have eaten Mertz after his death—surfaced during Mawson's lecture tour of the United States following the expedition. Several reports in American newspapers quoted Mawson as saying he considered eating Mertz, but these claims were denied by Mawson, who labelled them "outrageous" and an "invention".[94] Mawson's biographers believe the suggestion of cannibalism is probably wrong; Beau Riffenburgh notes that Mawson nursed Mertz for days, even at the possible risk to his own life. Moreover, he notes, Mawson had no way of knowing why Mertz died; eating his flesh could possibly have been very dangerous.[95] These sentiments are echoed by Philip Ayres, who also notes that with Mertz's death Mawson had sufficient rations without having to resort to cannibalism.[96] Law, who knew Mawson well, believed "He was a man of very solid, conservative morals. It would have been impossible for him to have considered it."[97]

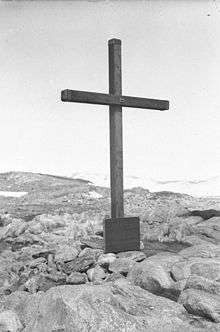

In November 1913, shortly before the Aurora arrived to return them to Australia, the men remaining at Cape Denison erected a memorial cross for Mertz and Ninnis on Azimuth Hill to the north-west of the main hut.[98] The cross, constructed from pieces of a broken radio mast, was accompanied by a plaque cut from wood from Mertz's bunk.[99] The cross still stands, although the crossbar has required reattaching several times, and the plaque was replaced with a replica in 1986. The two glaciers the Far Eastern Party crossed—previously unnamed—were named by Mawson for Mertz and Ninnis.[100][101] At a celebration in the centre of Adelaide on his return from Antarctica, Mawson praised his dead companions: "The survivors might have an opportunity of doing something more, but these men had done their all".[102]

Mawson's return was celebrated at the Adelaide Town Hall, in an event attended by the governor-general, Lord Denman. A typical speaker stated that "Mawson has returned from a journey that was absolutely unparalleled in the history of exploration—one of the greatest illustrations of how the sternest affairs of Nature were overcome by the superb courage, power and resolve of man".[103] Including the Far Eastern Party, sledging parties from the Cape Denison base covered over 2,600 miles (4,200 km) of previously unexplored land; the expedition's Western Base Party on the Shackleton Ice Shelf, under Frank Wild, covered a further 800 miles (1,300 km).[104]

The expedition was the first to use wireless radio in the Antarctic—transmitting back to Australia via a relay station established on Macquarie Island—and made several important scientific discoveries.[105] First published in 1915, Mawson's account of the expedition, The Home of the Blizzard, devotes two chapters to the Far Eastern Party;[106] one contemporary reviewer commented that "undoubtedly to the general public the interest of the book centres in [this] moving account".[107]

A later analysis by J. Gordon Hayes, while commending most of the expedition, was critical of Mawson's decision not to use skis, but Fred Jacka, writing in the Australian Dictionary of Biography, suggests that "for Mawson and Ninnis, who were manoeuvring heavy sledges, this would have been difficult much of the time".[105] In his 1976 foreword to Lennard Bickel's book on the Australasian Antarctic Expedition, explorer and mountaineer Sir Edmund Hillary described Mawson's journey as "probably the greatest story of lone survival in Polar exploration".[1]

See also

References

Notes

- For simplicity, this article refers to the Mertz and Ninnis Glaciers by the names given to them following the expedition. During the expedition itself they remained unnamed.

- The men's sledging rations consisted mainly of pemmican and plasmon biscuits, which could be ground, mixed with water and boiled to make a stew or soup known as hoosh. Added to the rations were basics such as butter, chocolate and tea; the daily ration was set at around 34 ounces (960 g) per man.[4]

- There was division as to which method of securing the dogs to the sledge was best; Mawson favoured the Yukon method, whereby the dogs were arranged in pairs, attached to a single line, with a man pulling in front, while Ninnis and Mertz preferred the Eskimo method, where the dogs were arranged in a fan-shape. Ninnis recorded that Mawson was concerned that in crevassed country the Eskimo method would mean "the whole show—sledges, dogs and men—would be more likely to go down [into a crevasse] together, whereas by the [Yukon] method only the man would go, and could be hoicked out again." While Ninnis continued to express his reservations about the Yukon method—chiefly that the lines easily became tangled and the long line put the farthest dogs out of range of the whip—by late October Mawson had settled on the technique, and Ninnis and Mertz devoted their time to accustoming the dogs.[13]

- Mawson calculated the weight of the supplies (including sledges) at 1,723 pounds (782 kg), of which food (for humans and dogs) and fuel made up 1,260 pounds (570 kg).[20]

- Mawson's diary on 21 November records "Dogs fed with Jappy [one of the other dogs, killed the previous day] and pups".[29] Mawson biographer Philip J. Ayres suggests the sledge dogs' consumption of the pups was "normal in these conditions".[30]

- Mertz's last entry in his diary was on 1 January, a week before his death. After he died, Mawson tore the remaining blank pages from the diary to save weight.[66]

Footnotes

- Edmund Hillary (1976) in Bickel (2000), p. x.

- Ayres (1999), p. 63.

- Bickel (2000), p. 43.

- Riffenburgh (2009), pp. 88–89.

- Ayres (1999), p. 67.

- Riffenburgh (2009), p. 87.

- Riffenburgh (2009), p. 90.

- Riffenburgh (2009), p. 98.

- Mawson (1996), p. 135.

- Riffenburgh (2009), p. 99.

- Bickel (2000), pp. 78–79.

- Riffenburgh (2009), p. 42.

- Riffenburgh (2009), p. 107.

- Bickel (2000), p. 67.

- Bickel (2000), p. 77.

- Bickel (2000), p. 81.

- Ayres (1999), p. 70.

- Bickel (2000), pp. 86–87.

- Riffenburgh (2009), p. 103.

- Bickel (2000), p. 87.

- Bickel (2000), pp. 90–91.

- Riffenburgh (2009), p. 105.

- Bickel (2000), p. 92.

- Riffenburgh (2009), pp. 106–107.

- Bickel (2000), p. 96.

- Mawson (1988), p. 132.

- Riffenburgh (2009), p. 106.

- Riffenburgh (2009), p. 108.

- Mawson (1988), p. 134.

- Ayres (1999), p. 72.

- Bickel (2000), pp. 99–100.

- Riffenburgh (2009), pp. 109–110.

- Riffenburgh (2009), pp. 108–109.

- Bickel (2000), p. 102.

- Mawson (1996), p. 146.

- Bickel (2000), p. 101.

- Mawson (1996), p. 151.

- Bickel (2000), p. 105.

- Riffenburgh (2009), p. 110.

- Riffenburgh (2009), pp. 110–111.

- Bickel (2000), p. 106.

- Bickel (2000), p. 107.

- Riffenburgh (2009), p. 112.

- Mawson (1988), p. 140.

- Bickel (2000), pp. 109–112.

- "Mawson's fatal journey". Mawson's Huts Foundation. Australian Antarctic Division. Retrieved 30 March 2012.

- Bickel (2000), p. 113.

- Riffenburgh (2009), p. 115.

- Hall and Scanlan (2000), p. 126.

- Mawson (1988), p. 148.

- Bickel (2000), p. 119.

- Ayres (1999), p. 73.

- Bickel (2000), p. 121.

- Ayres (1999), p. 74.

- Ayres (1999), pp. 74–75.

- Ayres (1999), p. 75.

- Riffenburgh (2009), p. 121.

- Riffenburgh (2009), p. 148.

- Bickel (2000), p. 147.

- Mawson (1988), p. 152.

- Riffenburgh (2009), pp. 123–124.

- Bickel (2000), p. 153.

- Riffenburgh (2009), p. 125.

- Mawson (1988), p. 155.

- Riffenburgh (2009), p. 127.

- Ayres (1999), p. 76.

- Mawson (1988), p. 156.

- Ayres (1999), pp. 76–77.

- Mawson (1988), p. 158.

- Ayres (1999), p. 77.

- Riffenburgh (2009), pp. 131–133.

- Ayres (1999), p. 79.

- Riffenburgh (2009), p. 135.

- Mawson (1988), p. 159.

- Bickel (2000), pp. 198–199.

- Mawson (1988), pp. 161–162.

- Ayres (1999), pp. 79–80.

- Riffenburgh (2009), p. 139.

- Ayres (1999), p. 81.

- Bickel (2000), p. 215.

- Riffenburgh (2009), p. 142.

- Riffenburgh (2009), p. 143.

- Bickel (2000), pp. 229–230.

- Riffenburgh (2009), p. 144.

- Ayres (1999), p. 82.

- Ayres (1999), pp. 86–87.

- Bickel (2000), p. 257.

- Riffenburgh (2009), p. 154.

- Bickel (2000), p. 259.

- Riffenburgh (2009), p. 136.

- Riffenburgh (2009), p. 137.

- Ayres (1999), pp. 80–81.

- Carrington-Smith (2005), p. 641.

- Riffenburgh (2009), pp. 131–132.

- Riffenburgh (2009), pp. 132–133.

- Ayres (1999), pp. 78–79.

- Ayres (1999), p. 78.

- "Mawson's fatal journey: Last gasp". Mawson's Huts Foundation. Australian Antarctic Division. Retrieved 30 March 2012.

- Bickel (2000), p. 254.

- "Mertz Glacier". Australian Antarctic Data Centre. Australian Antarctic Division. Retrieved 7 July 2011.

- "Ninnis Glacier". Australian Antarctic Data Centre. Australian Antarctic Division. Retrieved 7 July 2011.

- "Dr. Mawson's Reply", The Advertiser, National Library of Australia: 16, 4 March 1914

- Riffenburgh (2009), pp. 177–178.

- Ayres (1999), pp. 95–96.

- Jacka, Fred (1986). "Mawson, Sir Douglas (1882–1958)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Australian National University. Retrieved 7 July 2011.

- Mawson (1915), pp. 214–273.

- Mill (1915), p. 424.

Bibliography

- Ayres, Philip J. (1999), Mawson: a life, Carlton South, Victoria: Miegunyah Press at Melbourne University Press, ISBN 9780522848113

- Bickel, Lennard (2000) [1977], Mawson's Will: The Greatest Polar Survival Story Ever Written, Hanover, New Hampshire: Steerforth Press, ISBN 9781586420000

- Carrington-Smith, Denise (5–19 December 2005), "Mawson and Mertz: a re-evaluation of their ill-fated mapping journey during the 1911–1914 Australasian Antarctic Expedition", The Medical Journal of Australia, 183 (11/12): 638–641, PMID 16336159

- Hall, Lincoln; Scanlan, Barbara (research) (2000), Douglas Mawson: The Life of an Explorer, Sydney: New Holland, ISBN 9781864366709

- Mawson, Douglas (1915), The Home of the Blizzard: the story of the Australasian Antarctic Expedition, 1911–1914, London: William Heinemann

- Mawson, Douglas (1996) [1915], The Home of the Blizzard: the story of the Australasian Antarctic Expedition, 1911–1914, Kent Town, South Australia: Wakefield Press, ISBN 9781862543775

- Mawson, Douglas (1988), Jacka, Fred; Jacka, Eleanor (eds.), Mawson's Antarctic diaries, North Sydney: Allen & Unwin, ISBN 9780043202098

- Mill, Hugh Robert (May 1915), "The Australian Antarctic Expedition" (PDF), The Geographical Journal, 45 (5): 419–426, doi:10.2307/1779731

- Riffenburgh, Beau (2009) [2008], Racing with death: Douglas Mawson—Antarctic Explorer, London, New York and Berlin: Bloomsbury Publishing, ISBN 9780747596714

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to the Far Eastern Party. |