Kara-Khanid Khanate

The Kara-Khanid Khanate (Persian: قراخانیان, romanized: Qarākhāniyān), also known as the Karakhanids, Qarakhanids, Ilek Khanids[5] or the Afrasiabids (Persian: آل افراسیاب, romanized: Āl-i Afrāsiyāb, lit. 'House of Afrasiab'), was a Turkic khanate that ruled Central Asia in the 9th through the early 13th century. The dynastic names of Karakhanids and Ilek Khanids refer to royal titles with Kara Kağan being the most important Turkic title up till the end of the dynasty.[6]

Kara-Khanid Khanate | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 840–1212 | |||||||||||||||

Kara Khanid Khanate, c. 1000. | |||||||||||||||

| Capital | |||||||||||||||

| Common languages |

| ||||||||||||||

| Religion | |||||||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||||||

| Khagan, Khan | |||||||||||||||

• 840–893 (first) | Bilge Kul Qadir Khan | ||||||||||||||

• 1204–1212 (last) | Uthman Ulugh-Sultan | ||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||

• Established | 840 | ||||||||||||||

• Disestablished | 1212 | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Today part of | China Kazakhstan Kyrgyzstan Tajikistan Uzbekistan | ||||||||||||||

Part of a series on the |

||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History of Central Asia | ||||||||||||||||||

.jpg) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Ancient | ||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

| Middle Ages | ||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

| Colonization period | ||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

| Great game period | ||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

| Topics | ||||||||||||||||||

The Khanate conquered Transoxania in Central Asia and ruled it between 999–1211.[7][8] Their arrival in Transoxania signaled a definitive shift from Iranian to Turkic predominance in Central Asia,[9] yet the Kara-khanids gradually assimilated the Perso-Arab Muslim culture, while retaining some of their native Turkic culture.[1]

The capitals of the Kara-Khanid Khanate included Kashgar, Balasagun, Uzgen and Samarkand. In the 1040s, the Khanate split into the Eastern and Western Khanates. In the late 11th century, they came under the suzerainty of the Seljuks, followed by the Kara-Khitans in the mid-12th century. The Eastern Khanate was ended by the Kara-Khitans in 1211. The Western Khanate was extinguished by the Khwarazmian dynasty in 1213.

The history of the Kara-Khanid Khanate is reconstructed from fragmentary and often contradictory written sources, as well as studies on their coinage.[10]

Names

The term Karakhanid was derived from Qara Khan or Qara Khaqan (Persian: قراخان, romanized: Qarākhān), the foremost title of the rulers of the dynasty.[11] The word "Kara" means "black" and also "courageous" from Old Turkic (𐰴𐰺𐰀) and khan means ruler. The term was devised by European Orientalists in the 19th century to describe both the dynasty and the Turks ruled by it.[9]

- Arabic Muslim sources called this dynasty al-Khaqaniya ("That of the Khaqans") or al Muluk al-Khaniyya al-Atrak (The Khanal kings of the Turks).

- Persian sources often used the term Al-i Afrasiyab (Persian: آل افراسیاب, romanized: Āl-i Afrāsiyāb, lit. 'House of Afrisyab') based on a supposed link to the legendary though actually unrelated King Afrasiab of pre-Islamic Transoxania.[9] Mahmud al-Kashgari refers to him as Alp Er Tunga.[12]

- They are also referred to as Ilek Khanids or Ilak Khanids (Persian: ایلک خانیان, romanized: Ilak-Khānīyān) in Persian.[1]

- Chinese sources refer to this dynasty as Kalahan (Chinese: 喀喇汗) or Heihan (Chinese: 黑汗, literally "Black Khan") or Dashi (Chinese: 大食, a term for Arabs that extends to Muslims in general).[13][14]

History

Origin

The Kara-Khanid Khanate originated from a confederation formed some time in the 9th century by Karluks, Yagmas, Chigils, and other peoples living in Zhetysu, Western Tian Shan (modern Kyrgyzstan), and Western Xinjiang around Kashgar.[9] According to the 10th century Arab historian Al-Masudi, the khagans may be descendants of the Ashina.[15] They claimed the title khagan, which indicates that they may have been descended from the Ashina.[16]

Early history

The Karluks were a nomadic people from the western Altai Mountains who moved to Zhetysu. In 742, the Karluks were part of an alliance led by the Basmyl and Uyghurs that rebelled against the Göktürks.[17] In the realignment of power that followed, the Karluks were elevated from a tribe led by an el teber to one led by a yabghu, which was one of the highest Turkic dignitaries and also implies membership in the Ashina clan in whom the "heaven-mandated" right to rule resided. The Karluks and Uyghurs later allied themselves against the Basmyl, and within two years they toppled the Basmyl khagan. The Uyghur yabghu became khagan and the Karluk leader yabghu. This arrangement lasted less than a year. Hostilities between the Uyghur and Karluk forced the Karluk to migrate westward into the western Turgesh lands.[18]

By 766 the Karluks had forced the submission of the Turgesh and they established their capital at Suyab on the Chu River. The Karluk confederation by now included the Chigil and Tukshi tribes who may have been Türgesh tribes incorporated into the Karluk union. By the mid-9th century, the Karluk confederation had gained control of the sacred lands of the Western Türks after the destruction of the Uyghur Khaganate by the Old Kirghiz Control of sacred lands, together with their affiliation with the Ashina clan, allowed the Khaganate to be passed on to the Karluks along with domination of the steppes after the previous Khagan was killed in a revolt.[19]

During the 9th century southern Central Asia was under the rule of the Samanids, while the Central Asian steppe was dominated by Turkic nomads such as the Pechenegs, the Oghuz Turks, and the Karluks. The domain of the Karluks reached as far north as the Irtysh and the Kimek confederation, with encampments extending to the Chi and Ili rivers, where the Chigil and Tukshi tribes lived, and east to the Ferghana valley and beyond. The area to the south and east of the Karluks was inhabited by the Yagma.[20] The Karluk center in the 9th and 10th centuries appears to have been at Balasagun on the Chu River. In the late 9th century the Samanids marched into the steppes and captured Taraz, one of the headquarters of the Karluk khagan, and a large church was transformed into a mosque.

Formation of the Kara-Khanid Khanate

During the 9th century, the Karluk confederation (including the Türgesh descended Chigil and Tukshi tribes) and the Yaghma, possible descendants of the Toquz Oghuz, joined force and formed the first Karluk-Karakhanid khaganate. The Chigils appear to have formed the nucleus of the Karakhanid army. The date of its foundation and the name of its first khan is uncertain, but according to one reconstruction, the first Karakhanid ruler was Bilge Kul Qadir Khan.[21] The rulers of the Karakhanids were likely to be from the Chigil and Yaghma tribes – the Eastern Khagan bore the title Arslan Qara Khaqan (Arslan "lion" was the totem of the Chigil) and the Western Khagan the title Bughra Qara Khaqan (Bughra "male camel" was the totem of the Yaghma). The names of animals were a regular element in the Turkic titles of the Karakhanids: thus Aslan (lion), Bughra (camel), Toghan (falcon), Böri (wolf), and Toghrul or Toghrïl (a bird of prey).[10] Under the Khagans were four rulers with the titles Arslan Ilig, Bughra Ilig, Arslan Tegin and Bughra Tegin.[21] The titles of the members of the dynasty changed with their changing position, normally upwards, in the dynastic hierarchy.

In the mid-10th century the Kara-Khanids converted to Islam and adopted Muslim names and honorifics, but retained Turkic regnal titles such as Khan, Khagan, Ilek (Ilig) and Tegin.[10][22] Later they adopted Arab titles sultan and sultān al-salātīn (sultan of sultans). According to the Ottoman historian known as Munajjim-bashi, a Karakhanid prince named Sultan Satuq Bughra Khan was the first of the khans to convert. After conversion, he obtained a fatwa which permitted him in effect to kill his presumably still pagan father, after which he conquered Kashgar (of the old Shule Kingdom).[23] Later in 960, according to Muslim historians Ibn Miskawaih and Ibn al-Athir, there was a mass conversion of the Turks (reportedly "200,000 tents of the Turks"), circumstantial evidence suggests these were the Karakhanids.[23]

Conquest of Transoxiana

The grandson of Satuk Bughra Khan, Hasan b. Sulayman (or Harun) (title: Bughra Khan) attacked the Samanids in the late 10th century. Between 990–992, Hasan took Isfijab, Ferghana, Ilaq, Samarkand, and the Samanid capital Bukhara.[24] However, Hasan Bughra Khan died in 992 due to an illness,[24] and the Samanids returned to Bukhara.

Hasan's cousin Ali b. Musa (title: Kara Khan or Arslan Khan) resumed the campaign against the Samanids, and by 999 Ali's son Nasr had taken Chach, Samarkand, and Bukhara.[10] The Samanid domains were divided between the Ghaznavids, who gained Khorasan and Afghanistan, and the Karakhanids, who received Transoxiana. The Oxus River thus became the boundary between the two rival empires.

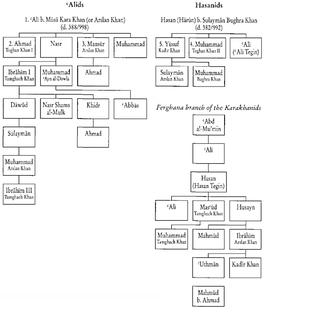

The Karakhanid state was divided into appanages, (Ülüş system) as was common of Turkic and Mongol nomads. The Karakhanid appanages were associated with four principal urban centers, Balasagun (then the capital of the Karakhanid state) in Zhetysu, Kashgar in Xinjiang, Uzgen in Fergana, and Samarkand in Transoxiana. The dynasty's original domains of Zhetysu and Kasgar and their khans retained an implicit seniority over those who ruled in Transoxiana and Fergana.[9] The four sons of Ali (Ahmad, Nasr, Mansur, Muhammad) each held their own independent appanage within the Karakhanid state. Nasr, the conqueror of Transoxiana, held the large central area of Transoxiana (Samarkand and Bukhara), Fergana (Uzgen) and other areas, although after his death his appanage was further divided. Ahmad held Zhetysu and Chach and became the head of the dynasty after the death of Ali. The brothers Ahmad and Nasr conducted different policies towards the Ghaznavids in the south – while Ahmad tried to form alliance with Mahmud of Ghazna, Nasr attempted to expand unsuccessfully into the territory of the Ghaznavids.[10]

Ahmad was succeeded by Mansur, and after the death of Mansur, the Hasan Bughra Khan branch of the Karakhanids became dominant. Hasan's sons Muhammad Toghan Khan II, and Yusuf Kadir Khan who held Kashgar, became in turn the head of the Karakhanid dynasty. The two families, i.e. the descendants of Ali Arslan Khan and Hasan Bughra Khan, would eventually split the Karakhanid Khanate in two.

In 1017–1018, the Karakhanids repelled an attack by a large mass of nomadic Turkic tribes in what was described in Muslim sources as a great victory.[25]

Conquest of western Tarim Basin

The Islamic conquest of the Buddhist cities east of Kashgar began when the Karakhanid Sultan Satuq Bughra Khan converted to Islam in 934 and then captured Kashgar. He and his son directed endeavors to proselytize Islam among the Turks and engage in military conquests.[26] In the mid-10th century, Satuq's son Musa began to put pressure on Khotan, and a long period of war between Kashgar and the Kingdom of Khotan ensued.[27] Satok Bughra Khan's nephew or grandson Ali Arslan was said to have been killed by Buddhists during the war;[28] during the reign of Ahmad b. Ali, the Karakhanids also engaged in wars against non-Muslims to the east and northeast.[29]

Muslim accounts tell the tale of the four imams from Mada'in city (possibly now in Iraq) who travelled to help Yusuf Qadir Khan, the Qarakhanid leader, in his conquest of Khotan, Yarkend, and Kashgar. The "infidels" were said to have been driven towards Khotan, however the four Imams were killed.[30] In 1006, Yusuf Qadir Khan of Kashgar conquered the Kingdom of Khotan, ending Khotan's existence as an independent state.[31]

The conquest of the western Tarim Basin which includes Khotan and Kashgar is significant in the eventual Turkification and Islamification of the Tarim Basin, and modern Uyghurs identify with the Karakhanids even though the name Uyghur was taken from the Manichaean Uyghur Khaganate and the Buddhist state of Qocho.[32][33]

Division of the Kara-Khanid Khanate

Early in the 11th century the unity of the Karakhanid dynasty was fractured by frequent internal warfare that eventually resulted in the formation of two independent Karakhanid states. A son of Hasan Bughra Khan, Ali Tegin, seized control of Bukhara and other towns. He expanded his territory further after the death of Mansur. The son of Nasr, Böritigin, later waged war against the sons of Ali Tegin, and won control of large part of Transoxania, and made Samarkand the capital. In 1041, another son of Nasr b. Ali, Muhammad 'Ayn ad-Dawlah (reigned 1041–52) took over the administration of the western branch of the family that eventually led to a formal separation of the Khara-Khanid Khanate. Ibrahim Tamghach Khan was considered by Muslim historians as a great ruler, and he brought some stability to Western Karakhanids by limiting the appanage system that caused much of the internal strife in the Kara-Khanid Khanate.[10]

The Hasan family remained in control of the Eastern Khanate. The Eastern Khanate had its capital at Balasaghun and later Kashgar. The Fergana-Zhetysu areas became the border between the two states and were frequently contested. When the two states were formed, Fergana fell into realm of the Eastern Khanate, but was later captured by Ibrahim and became part of Western Khanate.

Seljuk suzerainty

In 1040, the Seljuk Turks defeated the Ghaznavids at the Battle of Dandanaqan and entered Iran. Conflict with the Karakhanids broke out, but the Karakhanids were able to withstand attacks by the Seljuks initially, even briefly taking control of Seljuk towns in Greater Khorasan. The Karakhanids, however, developed serious conflicts with the religious classes (the ulama), and the ulama of Transoxiana then requested the intervention of the Seljuks. In 1089, during the reign of Ibrahim's grandson Ahmad b. Khidr, the Seljuks entered and took control of Samarkand, together with the domains belonging to the Western Khanate. The Western Karakhanids Khanate became a vassal of the Seljuks for half a century, and the rulers of the Western Khanate were largely whomever the Seljuks chose to place on the throne. Ahmad b. Khidr was returned to power by the Seljuks, but in 1095, the ulama accused Ahmad of heresy and managed to secure his execution.[10]

The Karakhanids of Kashgar also declared their submission following a Seljuk campaign into Talas and Zhetysu, but the Eastern Khanate was a Seljuk vassal for only a short time. At the beginning of the 12th century they invaded Transoxiana and briefly occupied the Seljuk town of Termez.[10]

Qara Khitai Invasion

The Qara Khitai host which invaded Central Asia was composed of remnants from the defunct Liao dynasty which was annihilated by the Jurchens in 1125. The Khitan noble Yelü Dashi recruited warriors from various tribes and formed a horde that moved westward to rebuild the Khitan nation. Yelu occupied Balasagun on the Chu River, then defeated the Western Karakhanids in Khujand in 1137.[34] In 1141 Qara Khitai became the dominant force in the region after they dealt a devastating blow to the Seljuk Sultan Ahmad Sanjar at the Battle of Qatwan near Samarkand.[9] Several military commanders of Karakhanid lineages such as the father of Osman of Khwarazm fled from Karakhanid lands in the wake of the Qara Khitai invasion.

Despite losing to the Qara Khitai, the Karakhanid dynasty remained in power as their vassals. The Qara Khitai themselves stayed at Zhetysu near Balasagun, and allowed some of the Karakhanids to continue to rule as their tax collectors in Samarkand and Kashgar. Under the Qara Khitai the Karakhanids functioned as administrators for sedentary Muslim populations. While the Qara Khitai were Buddhists ruling over a largely Muslim population, they were considered fair-minded rulers whose reign was marked by religious tolerance.[9] Islamic religious life continued uninterrupted and Islamic authority persevered under the Qara Khitai. Kashgar became a Nestorian metropolitan see and Christian gravestones in the Chu River Valley appeared beginning in this period.[34] However, Kuchlug, a Naiman who usurped the throne of the Qara Khitai Dynasty, instituted anti-Islamic policies on the local populations under his rule.[35]

Downfall

The decline of the Seljuks following their defeat by the Qara Khitans allowed the Khwarazmian dynasty, then a vassal of the Qara Khitai, to expand into former Seljuk territory. In 1207, the citizens of Bukhara revolted against the sadrs (leaders of the religious classes), which the Khwarezm-Shah 'Ala' ad-Din Muhammad used as a pretext to conquer Bukhara. Muhammad then formed an alliance with the Western Karakhanid ruler Uthman (who later married Muhammad's daughter) against the Qara Khitai. In 1210, the Khwarezm-Shah took Samarkand after the Qara Khitai retreated to deal with the rebellion from the Naiman Kuchlug, who had seized the Qara Khitans' treasury at Uzgen.[10] The Khwarezm-Shah then defeated the Qara Khitai near Talas. Muhammad and Kuchlug had, apparently, agreed to divide up the Qara Khitan's empire.[36] In 1212, the population of Samarkand staged a revolt against the Khwarezmians, a revolt which Uthman supported, and massacred them. The Khwarezm-Shah returned, recaptured Samarkand and executed Uthman. He demanded the submission of all leading Karakhanids, and finally extinguished the Western Karakhanid state.

In 1204, a rebellion of the Eastern Kara-Khanid in Kashgar was suppressed by the Kara-Khitai who took the prince Yusuf hostage to Balasagun.[37] The prince was later released but he was killed in Kashgar by rebels in 1211, effectively ending the Eastern Kara-Khanid.[37] In 1214, the rebels in Kashgar surrendered to Kuchlug, who had usruped the Kara-Khitai throne.[37] In 1218, Kuchlug was killed by the Mongol army. Some of the Kara-Khitai's eastern vassels including Eastern Kara-Khanids then joined the Mongol forces that conquered the Khwarezmian Empire.[38]

Culture

The takeover by the Karakhanids did not change the essentially Iranian character of Central Asia, though it set into motion a demographic and ethnolinguistic shift. During the Karakhanid era, the local population began using Turkic in speech – initially the shift was linguistic with the local people adopting the Turkic language.[39] While Central Asia became Turkicized over the centuries, culturally the Turks came close to being Persianized or, in certain respects, Arabicized.[9] Nevertheless, the official or court language used in Kashgar and other Karakhanid centers, referred to as "Khaqani" (royal), remained Turkic. The language was partly based on dialects spoken by the Turkic tribes that made up the Karakhanids and possessed qualities of linear descent from Kök and Karluk Turkic. The Turkic script was also used for all documents and correspondence of the khaqans, according to Dīwānu l-Luġat al-Turk.[40]

The Dīwānu l-Luġat al-Turk (Dictionary of Languages of the Turks) was written by a prominent Karakhanid historian, Mahmud al-Kashgari, who may have lived for some time in Kashgar at the Karakhanid court. He wrote this first comprehensive dictionary of Turkic languages in Arabic for the Caliphs of Baghdad in 1072–76. Another famous Karakhanid writer was Yusuf Balasaghuni, who wrote Kutadgu Bilig (The Wisdom of Felicity), the only known literary work written in Turkic from the Karakhanid period.[40] Kutadgu Bilig is a form of advice literature known as mirrors for princes.[41] The Turkic identity is evident in both of these pieces of work, but they also showed the influences of Persian and Islamic culture.[42] However, the court culture of the Karakhanids remained almost entirely Persian.[42] The two last western khaqans also wrote poetry in Persian.[1]

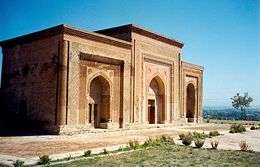

Islam and its civilization flourished under the Karakhanids. The earliest example of madrasas in Central Asia was founded in Samarkand by Ibrahim Tamghach Khan. Ibrahim also founded a hospital to care for the sick as well as providing shelter for the poor.[10] His son Nasr Shams al-Mulk built ribats for the caravanserais on the route between Bukhara and Samarkand, as well as a palace near Bukhara. Some of the buildings constructed by the Karakhanids still survive today, including the Kalyan minaret built by Mohammad Aslan Khan beside the main mosque in Bukhara, and three mausolea in Uzgend. The early Karakhanid rulers, as nomads, lived not in the city but in an army encampment outside the capital, and while by the time of Ibrahim the Karakhanids still maintained a nomadic tradition, their extensive religious and civil constructions showed that they had assimilated the culture and traditions of the settled population of Transoxiana.[10]

Genetics

A genetic study published in Nature in May 2018 examined the remains of three Khara-Khanid individuals.[43] They were found to be carrying the maternal haplogroups G2a2, A and J1c.[44] The Kara-Khanid were found be have more East Asian ancestry than the preceding Goktürks.[45]

Legacy

Kara-Khanid is arguably the most enduring cultural heritage among coexisting cultures in Central Asia from the 9th to the 13th centuries. The Karluk-Uyghur dialect spoken by the nomadic tribes and turkified sedentary populations under Kara-Khanid rule formed two major branches of the Turkic language family, the Chagatay and the Kypchak. The Kara-Khanid cultural model that combined nomadic Turkic culture with Islamic, sedentary institutions spread east into former Kara-Khoja and Tangut territories and west and south into the subcontinent, Khorasan (Turkmenistan, Afghanistan, and Northern Iran), Golden Horde territories (Tataristan), and Turkey. The Chagatay, Timurid, and Uzbek states and societies inherited most of the cultures of the Kara-Khanids and the Khwarezmians without much interruption.

Kara-Khanid dynasty

| History of the Turkic peoples pre-14th century |

|---|

History of the Turkic peoples |

| Tiele people |

| Göktürks |

|

| Khazar Khaganate 618–1048 |

| Xueyantuo 628–646 |

| Kangar union 659–750 |

| Turk Shahi 665-850 |

| Türgesh Khaganate 699–766 |

| Kimek confederation 743–1035 |

| Uyghur Khaganate 744–840 |

| Oghuz Yabgu State 750–1055 |

| Karluk Yabgu State 756–940 |

| Kara-Khanid Khanate 840–1212 |

| Ganzhou Uyghur Kingdom 848–1036 |

| Qocho 856–1335 |

| Pecheneg Khanates 860–1091 |

| Ghaznavid Empire 963–1186 |

| Seljuk Empire 1037–1194 |

| Cumania 1067–1239 |

| Khwarazmian Empire 1077–1231 |

| Kerait Khanate 11th century–13th century |

| Delhi Sultanate 1206–1526 |

| Qarlughid Kingdom 1224–1266 |

| Golden Horde 1240s–1502 |

| Mamluk Sultanate (Cairo) 1250–1517 |

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Xinjiang |

|

|

Medieval and early modern period |

- Bilge Kul Qadir Khan (840–893)

- Bazir Arslan Khan (893–920)

- Oghulcak Khan (893–940)

- Satuk Bughra Khan 920–955, in 932 adopted Islam,[46] in 940 took power over Karluks

- Musa Bughra Khan 955–958

- Suleyman Arslan Khan 958–970

- Ali Arslan Khan 970–998, Great Qaghan

- Ahmad Arslan Qara Khan 998–1017, son of Ali Arslan

- Mansur Arslan Khan 1017–1024, son of Ali Arslan

- Muhammad Toghan Khan 1024–1026, son of Hasan b. Sulayman

- Yusuf Qadir Khan 1026–1032, son of Hasan b. Sulayman

- Ali Tigin Bughra Khan (1020–1034), Great Qaghan in Samarkand, son of Hasan b. Sulayman

- Ebu Shuca Sulayman 1034–1042

Western Karakhanids

- Muhammad Arslan Qara Khan c. 1042–c. 1052

- Tamghach Khan Ibrahim (also known as Böritigin) c. 1052–1068

- Nasr Shams al-Mulk 1068–1080: married Aisha, daughter of Alp Arslan.[47]

- Khidr 1080–1081

- Ahmad 1081–1089

- Ya'qub Qadir Khan 1089–1095

- Mas'ud 1095–1097

- Sulayman Qadir Tamghach 1097

- Mahmud Arslan Khan 1097–1099

- Jibrail Arslan Khan 1099–1102

- Muhammad Arslan Khan 1102–1129

- Nasr 1129

- Ahmad Qadir Khan 1129–1130

- Hasan Jalal ad-Dunya 1130–1132

- Ibrahim Rukn ad-Dunya 1132

- Mahmud 1132–1141

- Ibrahim Tabghach Khan 1141–1156

- Ali Chaghri Khan 1156–1161

- Mas'ud Tabghach Khan 1161–1171

- Muhammad Tabghach Khan 1171–1178

- Ibrahim Arslan Khan 1178–1204

- Uthman Ulugh Sultan 1204–1212

Eastern Karakhanids

- Ebu Shuca Sulayman 1042–1056

- Muhammad bin Yusuph 1056–1057

- İbrahim bin Muhammad Khan 1057–1059

- Mahmud 1059–1075

- Umar 1075

- Ebu Ali el-Hasan 1075–1102

- Ahmad Khan 1102–1128

- İbrahim bin Ahmad 1128–1158

- Muhammad bin İbrahim 1158–?

- Yusuph bin Muhammad ?–1205

- Ebul Feth Muhammad 1205–1211

See also

- Khanate

- Göktürks

- Uyghur Khaganate

- Uyghur people

- Karluks

- Chigils

- Yaghmas

- List of Sunni Muslim dynasties

- History of the central steppe

References

- Michal Biran (March 27, 2012). "ILAK-KHANIDS". Encyclopedia Iranica. Archived from the original on September 9, 2015. Retrieved May 12, 2014.

The two last western ḵāqāns, Ebrāhim b. Ḥo-sayn (1178-1203) and ʿOṯmān (1202-12), wrote poetry in Persian

- V.V. Barthold, Four Studies on the History of Central Asia, (E.J. Brill, 1962), 99.

- Grousset 1991, p. 165.

- Janhunen 2006, p. 114.

- "Qara-khanids", Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Africa and the Middle East, Vol. 1, Ed. Jamie Stokes, (Infobase Publishing, 2009), p. 578.

- Asimov 1998, p. 120.

- "Encyclopædia Britannica". Archived from the original on 2008-12-02. Retrieved 2006-12-08.

- Grousset 2004.

- Soucek 2000.

- Asimov 1998, p. 119-144.

- Golden 1990, p. 354.

- Osman Aziz Basan, (2010), The Great Seljuqs: A History, p. 177

- Biran, Michal (2016). "Karakhanid Khanate" (PDF). In John M. MacKenzie (ed.). The Encyclopedia of Empire. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. ISBN 978-1118440643. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-08-26. Retrieved 2017-05-04.

- Biran, Michal (2001). "Qarakhanid Studies: A View from the Qara Khitai Edge". Cahiers d'Asie centrale. 9: 77–89. Archived from the original on 2017-08-26. Retrieved 2017-05-04.

- Boris Zhivkov, (2010), Khazaria in the Ninth and Tenth Centuries, p. 46

- Carter V. Findley, (2004), The Turks in World History p. 75

- Beckwith 2009, p. 142.

- Golden 1990, p. 349.

- Golden 1990, p. 350-351.

- Golden 1990, p. 348.

- Golden 1990, p. 355-356.

- "Asia Research Institute Working Paper Series No.44 A History of Uighur Religious Conversions (5th-16th Centuries) by Li Tang". Archived from the original on 2008-01-19. Retrieved 2008-01-19.

- Golden 1990, p. 357.

- The Samanids, Richard Nelson Frye, The Cambridge History of Iran, Vol. 4, ed. R. N. Frye, (Cambridge University Press, 1999), 156-157.

- Golden 1990, p. 363.

- Hansen 2012, p. 226.

- Millward 2009, p. 55-56.

- Trudy Ring; Robert M. Salkin; Sharon La Boda (1994). International Dictionary of Historic Places: Asia and Oceania. Taylor & Francis. pp. 457–. ISBN 978-1-884964-04-6. Archived from the original on 2016-05-10. Retrieved 2015-10-12.

- Moriyasu 2004, p. 207.

- Thum 2012, p. 633.

- Aurel Stein, Ancient Khotan Archived 2011-09-12 at the Wayback Machine, Clarendon Press, pg 181.

- Millward 2009, p. 52-56.

- Starr 2015, p. 42.

- Asimov 1998.

- Biran 2005, p. 194-196.

- Golden 1990, p. 370.

- Biran 2005, p. 81.

- Biran 2005, p. 87.

- Golden 2011.

- Larry Clark (2010), "The Turkic script and Kutadgu Bilig", Turkology in Mainz, Otto Harrasowitz GmbH & Co, p. 96, ISBN 978-3-447-06113-1

- Scott Cameron Levi; Ron Sela (2010). "Chapter 13 - Yusuf Hass Hajib: Advice to the Qarakhanid Rulers". Islamic Central Asia: An Anthology of Historical Sources. Indiana University Press. pp. 76–81. ISBN 978-0-253-35385-6.

- Tetley 2009, p. 27.

- Damgaard et al. 2018, Supplementary Table 2, Rows 117-119.

- Damgaard et al. 2018, Supplementary Table 8, Rows 60-62.

- Damgaard et al. 2018, p. 4.

- Grousset 2004, p. 145.

- Ann K. S. Lambton, Continuity and Change in Medieval Persia, (State University of New York, 1988), 263.

Bibliography

- Andrade, Tonio (2016), The Gunpowder Age: China, Military Innovation, and the Rise of the West in World History, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-13597-7.

- Asimov, M.S. (1998), History of civilizations of Central Asia Volume IV The age of achievement: A.D. 750 to the end of the fifteenth century Part One The historical, social and economic setting, UNESCO Publishing

- Barfield, Thomas (1989), The Perilous Frontier: Nomadic Empires and China, Basil Blackwell

- Barrett, Timothy Hugh (2008), The Woman Who Discovered Printing, Great Britain: Yale University Press, ISBN 978-0-300-12728-7 (alk. paper)

- Beckwith, Christopher I (1987), The Tibetan Empire in Central Asia: A History of the Struggle for Great Power among Tibetans, Turks, Arabs, and Chinese during the Early Middle Ages, Princeton University Press

- Beckwith, Christopher I (2009), Empires of the Silk Road, Princeton University Press

- Biran, Michal (2005), The Empire of the Qara Khitai in Eurasian History: Between China and the Islamic World, Cambridge University Press

- Bregel, Yuri (2003), An Historical Atlas of Central Asia, Brill

- Davidovich, E. A. (1998), "The Karakhanids", in Asimov, M.S.; Bosworth, C.E. (eds.), History of Civilisations of Central Asia (PDF), 4 part I, UNESCO Publishing, p. 120, ISBN 92-3-103467-7

- Damgaard, P. B.; et al. (May 9, 2018). "137 ancient human genomes from across the Eurasian steppes". Nature. Nature Research. 557 (7705): 369–373. doi:10.1038/s41586-018-0094-2. PMID 29743675. Retrieved April 11, 2020.

- Drompp, Michael Robert (2005), Tang China And The Collapse Of The Uighur Empire: A Documentary History, Brill

- Ebrey, Patricia Buckley (1999), The Cambridge Illustrated History of China, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-66991-X (paperback).

- Ebrey, Patricia Buckley; Walthall, Anne; Palais, James B. (2006), East Asia: A Cultural, Social, and Political History, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, ISBN 0-618-13384-4

- Golden, Peter. B. (1990), "The Karakhanids and Early Islam", in Sinor, Denis (ed.), The Cambridge History of Early Inner Asia, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-2-4304-1

- Golden, Peter B. (1992), An Introduction to the History of the Turkic Peoples: Ethnogenesis and State-Formation in Medieval and Early Modern Eurasia and the Middle East, OTTO HARRASSOWITZ · WIESBADEN

- Golden, Peter B. (2011), Central Asia in World History, Oxford University Press

- Graff, David A. (2002), Medieval Chinese Warfare, 300-900, Warfare and History, London: Routledge, ISBN 0415239559

- Graff, David Andrew (2016), The Eurasian Way of War Military Practice in Seventh-Century China and Byzantium, Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-46034-7.

- Grousset, Rene (2004), The Empire of the Steppes, Rutgers University Press

- Hansen, Valerie (2012), The Silk Road: A New History, Oxford University Press

- Haywood, John (1998), Historical Atlas of the Medieval World, AD 600-1492, Barnes & Noble

- Latourette, Kenneth Scott (1964), The Chinese, their history and culture, Volumes 1-2, Macmillan

- Lorge, Peter A. (2008), The Asian Military Revolution: from Gunpowder to the Bomb, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-60954-8

- Millward, James (2009), Eurasian Crossroads: A History of Xinjiang, Columbia University Press

- Moriyasu, Takao (2004), Die Geschichte des uigurischen Manichäismus an der Seidenstrasse: Forschungen zu manichäischen Quellen und ihrem geschichtlichen Hintergrund, Otto Harrassowitz Verlag

- Needham, Joseph (1986), Science & Civilisation in China, V:7: The Gunpowder Epic, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-30358-3

- Rong, Xinjiang (2013), Eighteen Lectures on Dunhuang, Brill

- Shaban, M. A. (1979), The ʿAbbāsid Revolution, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-29534-3

- Sima, Guang (2015), Bóyángbǎn Zīzhìtōngjiàn 54 huánghòu shīzōng 柏楊版資治通鑑54皇后失蹤, Yuǎnliú chūbǎnshìyè gǔfèn yǒuxiàn gōngsī, ISBN 978-957-32-0876-1

- Skaff, Jonathan Karam (2012), Sui-Tang China and Its Turko-Mongol Neighbors: Culture, Power, and Connections, 580-800 (Oxford Studies in Early Empires), Oxford University Press

- Soucek, Svatopluk (2000), A history of Inner Asia, Cambridge University Press

- Starr, S. (2015), Xinjiang: China's Muslim Borderland, Routledge

- Tetley, G.E. (2009), Ghaznavid and Seljuk Turks: Poetry as a Source for Iranian History, Routledge

- Thum, Rian (2012), Modular History: Identity Maintenance before Uyghur Nationalism, The Association for Asian Studies, Inc.

- Wang, Zhenping (2013), Tang China in Multi-Polar Asia: A History of Diplomacy and War, University of Hawaii Press

- Wilkinson, Endymion (2015). Chinese History: A New Manual, 4th edition. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Asia Center distributed by Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674088467.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Yuan, Shu (2001), Bóyángbǎn Tōngjiàn jìshìběnmò 28 dìèrcìhuànguánshídài 柏楊版通鑑記事本末28第二次宦官時代, Yuǎnliú chūbǎnshìyè gǔfèn yǒuxiàn gōngsī, ISBN 957-32-4273-7

- Xiong, Victor Cunrui (2000), Sui-Tang Chang'an: A Study in the Urban History of Late Medieval China (Michigan Monographs in Chinese Studies), U OF M CENTER FOR CHINESE STUDIES, ISBN 0892641371

- Xiong, Victor Cunrui (2009), Historical Dictionary of Medieval China, United States of America: Scarecrow Press, Inc., ISBN 978-0810860537

- Xue, Zongzheng (1992), Turkic peoples, 中国社会科学出版社