Jaguar

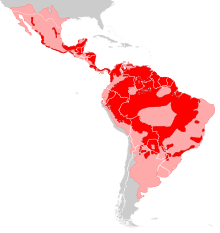

The jaguar (Panthera onca) is a large felid species and the only extant member of the genus Panthera native to the Americas. The jaguar's present range extends from southwestern United States and Mexico in North America, across much of Central America, and south to Paraguay and northern Argentina in South America. Though there are single cats now living within the western United States, the species has largely been extirpated from the United States since the early 20th century. It is listed as Near Threatened on the IUCN Red List; and its numbers are declining. Threats include loss and fragmentation of habitat.

| Jaguar | |

|---|---|

_male_Three_Brothers_River_2.jpg) | |

| Jaguar at Three Brothers River, Brazil | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Suborder: | Feliformia |

| Family: | Felidae |

| Subfamily: | Pantherinae |

| Genus: | Panthera |

| Species: | P. onca |

| Binomial name | |

| Panthera onca | |

| |

| Current (red) and former range (pink) | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Overall, the jaguar is the largest native cat species of the New World and the third largest in the world. This spotted cat closely resembles the leopard, but is usually larger and sturdier. It ranges across a variety of forested and open terrains, but its preferred habitat is tropical and subtropical moist broadleaf forest, swamps and wooded regions. The jaguar enjoys swimming and is largely a solitary, opportunistic, stalk-and-ambush predator at the top of the food chain. As a keystone species it plays an important role in stabilizing ecosystems and regulating prey populations.

While international trade in jaguars or their body parts is prohibited, the cat is still frequently killed, particularly in conflicts with ranchers and farmers in South America. Although reduced, its range remains large. Given its historical distribution, the jaguar has featured prominently in the mythology of numerous indigenous peoples of the Americas, including those of the Maya and Aztec civilizations.

Etymology

The word 'jaguar' is derived from 'iaguara', a word in one of the indigenous languages of Brazil for a wild spotted cat that is larger than a wolf.[2] Onca is derived from the Lusitanian name 'onça' for a spotted cat in Brazil that is larger than a lynx.[3] Indigenous peoples in Guyana call it 'jaguareté'.[4]

The word 'panther' derives from classical Latin panthēra, itself from the ancient Greek pánthēr (πάνθηρ).[5]

Taxonomy

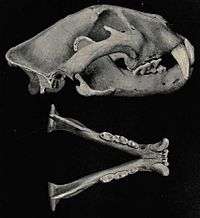

In 1758, Carl Linnaeus described the jaguar in his work Systema Naturae and gave it the scientific name Felis onca.[6] In the 19th and 20th centuries, several jaguar type specimens formed the basis for descriptions of subspecies.[7] In 1939, Reginald Innes Pocock recognized eight subspecies based on geographic origins and skull morphology of these specimens.[8] Pocock did not have access to sufficient zoological specimens to critically evaluate their subspecific status, but expressed doubt about the status of several. Later consideration of his work suggested only three subspecies should be recognized. The description of P. o. palustris was based on a fossil skull.[9] By 2005, nine subspecies were considered to be valid taxa.[7]

- P. o. onca (Linnaeus, 1758) was a jaguar from Brazil.[6]

- P. o. peruviana (De Blainville, 1843) was a jaguar skull from Peru.[10]

- P. o. hernandesii (Gray, 1857) was a jaguar from Mazatlán in Mexico.[11]

- P. o. palustris (Ameghino, 1888) was a fossil jaguar mandible excavated in the Sierras Pampeanas of Córdova District, Argentina.[12]

- P. o. centralis (Mearns, 1901) was a skull of a male jaguar from Talamanca, Costa Rica.[13]

- P. o. goldmani (Mearns, 1901) was a jaguar skin from Yohatlan in Campeche, Mexico.[13]

- P. o. paraguensis (Hollister, 1914) was a skull of a male jaguar from Paraguay.[14]

- P. o. arizonensis (Goldman, 1932) was a skin and skull of a male jaguar from the vicinity of Cibecue, Arizona.[15]

- P. o. veraecrucis (Nelson and Goldman, 1933) was a skull of a male jaguar from San Andrés Tuxtla in Mexico.[16]

Reginald Innes Pocock placed the jaguar in the genus Panthera and observed that it shares several morphological features with the leopard (P. pardus). He therefore concluded that they are most closely related to each other.[8] Results of morphologic and genetic research indicate a clinal north–south variation between populations, but no evidence for subspecific differentiation.[17][18] A subsequent, more detailed study confirmed the predicted population structure within jaguar populations in Colombia.[19]

Since 2017, the jaguar is therefore considered to be a monotypic taxon.[20]

Evolution

The genus Panthera probably evolved in Asia between 6 to 10 million years ago.[21] Phylogenetic studies generally have shown the clouded leopard (Neofelis nebulosa) is basal to this group.[22][23][24]

The jaguar is thought to have genetically diverged from a common ancestor of the Panthera at least 1.5 million years ago and to have entered the American continent in the Early Pleistocene via Beringia, the land bridge that once spanned the Bering Strait. Results of jaguar mitochondrial DNA analysis indicate that the species' lineage evolved between 280,000 and 510,000 years ago.[17] Fossils of the extinct Panthera gombaszoegensis and the American lion (P. atrox) show characteristics of both the jaguar and the lion (P. leo).[22] Results of DNA-based studies are conclusive, and the position of the jaguar relative to the other species varies depending on methods and sample sizes used.[21][22][23][24]

Its immediate ancestor was Panthera onca augusta, which was larger than the contemporary jaguar.[19] Jaguar fossils were discovered in Whitman County, Washington, Fossil Lake (Oregon), Niobrara, Nebraska, Franklin County, Tennessee, Edwards County, Texas, and in eastern Florida. A skeleton and pug marks of a jaguar were found in the Craighead Caverns. These fossils are dated to the Pleistocene between 40,000 and 11,500 years ago.[25]

Characteristics

_(6766663197).jpg)

.jpg)

The jaguar is a compact and well-muscled animal. It is the largest cat native to the Americas and the third largest in the world, exceeded in size by the tiger and the lion.[9][26][27] Its coat is generally a tawny yellow, but ranges to reddish-brown, for most of the body. The ventral areas are white.[15] The fur is covered with rosettes for camouflage in the dappled light of its forest habitat. The spots and their shapes vary between individual jaguars: rosettes may include one or several dots. The spots on the head and neck are generally solid, as are those on the tail, where they may merge to form a band.[9] Jaguars living in forests are often darker and considerably smaller than those living in open areas, possibly due to the smaller numbers of large, herbivorous prey in forest areas.[28]

Its size and weight vary considerably: weights are normally in the range of 56–96 kg (123–212 lb). Exceptionally big males have been recorded to weigh as much as 158 kg (348 lb).[29][30] The smallest females weigh about 36 kg (79 lb).[29] It is sexually dimorphic with females typically 10–20% smaller than males. The length, from the nose to the base of the tail, varies from 1.12 to 1.85 m (3 ft 8 in to 6 ft 1 in). The tail is the shortest of any big cat, at 45 to 75 cm (18 to 30 in) in length.[29][31] Legs are also short, but thick and powerful, considerably shorter when compared to a small tiger or lion in a similar weight range. The jaguar stands 63 to 76 cm (25 to 30 in) tall at the shoulders.[32]

Further variations in size have been observed across regions and habitats, with size tending to increase from north to south. Jaguars in the Chamela-Cuixmala Biosphere Reserve on the Pacific coast weighed around 50 kg (110 lb), about the size of a female cougar.[33] Jaguars in Venezuela and Brazil are much larger with average weights of about 95 kg (209 lb) in males and of about 56–78 kg (123–172 lb) in females.[9]

A short and stocky limb structure makes the jaguar adept at climbing, crawling, and swimming.[32] The head is robust and the jaw extremely powerful, it has the third highest bite force of all felids, after the tiger and the lion.[34] A 100 kg (220 lb) jaguar can bite with a force of 4.939 kilonewtons (1,110 pounds-force) with the canine teeth and 6.922 kN (1,556 lbf) at the carnassial notch.[35] It was ranked as the top felid in a comparative study of bite force adjusted for body size, alongside the clouded leopard and ahead of the tiger and lion.[36]

While the jaguar closely resembles the leopard, it is generally more robust, with stockier limbs and a squarer head. The rosettes on a jaguar's coat are larger, darker, fewer in number and have thicker lines with a small spot in the middle.[37]

Color variation

Melanistic jaguars are informally known as black panthers. The black morph is less common than the spotted one.[38] Melanism in the jaguar is caused by deletions in the melanocortin 1 receptor gene and inherited through a dominant allele.[39]

In Mexico's Sierra Madre Occidental, the first black jaguar was recorded in 2004.[40] Black jaguars were also recorded in Costa Rica's Alberto Manuel Brenes Biological Reserve and in the mountains of the Cordillera de Talamanca.[41][42]

Albino jaguars, sometimes called white panthers, are extremely rare.[28]

Distribution and habitat

_male_back_in_the_water_(29173428825).jpg)

At present, the jaguar's range extends from Mexico through Central America to South America, including much of Amazonian Brazil. The countries included in this range are Argentina, Belize, Bolivia, Colombia, Costa Rica (particularly on the Osa Peninsula), Ecuador, French Guiana, Guatemala, Guyana, Honduras, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Suriname, the United States and Venezuela. It is now locally extinct in El Salvador and Uruguay.[1]

The jaguar prefers dense forest and typically inhabits dry deciduous forests, tropical and subtropical moist broadleaf forests, rainforests and cloud forests in Central and South America; open, seasonally flooded wetlands, dry grassland and historically also oak forests in the United States. It has been recorded at elevations up to 3,800 m (12,500 ft), but avoids montane forests. It favours riverine habitat and swamps with dense vegetation cover.[28] It has lost habitat most rapidly in drier regions such as the Argentine pampas, the arid grasslands of Mexico and the southwestern United States.[1]

The jaguar's historic range included much of the southern part of the United States and extended much farther in the south, covering most of South America. In total, its northern range has receded 1,000 km (600 mi) southward and its southern range 2,000 km (1,200 mi) northward.[43] The jaguar was said to have occurred in the Monterey, California region in the early 19th century.[44] Occasional sightings were reported in Arizona,[45] New Mexico and Texas.[46]

Ecology and behavior

Ecological role

The adult jaguar is an apex predator, meaning it is at the top of the food chain and is not preyed upon in the wild. The jaguar has also been termed a keystone species, as it is assumed that it controls the population levels of prey such as herbivorous and granivorous mammals, and thus maintains the structural integrity of forest systems.[33][47]

However, accurately determining what effect species like the jaguar have on ecosystems is difficult, because data must be compared from regions where the species is absent as well as its current habitats, while controlling for the effects of human activity. It is accepted that mid-sized prey species undergo population increases in the absence of the keystone predators, and this has been hypothesized to have cascading negative effects.[48] However, field work has shown this may be natural variability and the population increases may not be sustained. Thus, the keystone predator hypothesis is not accepted by all scientists.[49]

The jaguar also has an effect on other predators. The jaguar and the cougar, which is the next-largest feline of South America, but the biggest in Central or North America,[33] are often sympatric (related species sharing overlapping territory) and have often been studied in conjunction. The jaguar tends to take larger prey, usually over 22 kg (49 lb) and the cougar smaller, usually between 2 and 22 kg (4 and 49 lb), reducing the latter's size.[50] This situation may be advantageous to the cougar. Its broader prey niche, including its ability to take smaller prey, may give it an advantage over the jaguar in human-altered landscapes;[33] while both are classified as near-threatened species, the cougar has a significantly larger current distribution. Depending on the availability of prey, the cougar and jaguar may even share it.[51]

Hunting and diet

Like all cats, the jaguar is an obligate carnivore, feeding only on meat. It is an opportunistic hunter, and its diet encompasses at least 87 species.[28] It prefers prey weighing 45–85 kg (99–187 lb), with capybara (Hydrochoerus hydrochaeris) and giant anteater (Myrmecophaga tridactyla) being the most preferred species. Other commonly taken prey include wild boar (Sus scrofa), Odocoileus deer, collared peccary (Pecari tajacu), spectacled caiman (Caiman crocodilus) in the northern parts of its range, nine-banded armadillo (Dasypus novemcinctus), white-nosed coati (Nasua narica), frogs, and fish.[26] Jaguars are unusual among large felids in that they do not have a special preference for even-toed ungulates.[26][52] Some jaguars also prey on livestock and they will actively target horses, cattle, and llamas.[53]

Its bite force allows it to pierce the shells of armored reptiles and turtles.[54] It bites into the throat of South American tapir (Tapirus terrestris) and other large prey until the victim suffocates. It kills capybara by piercing its canine teeth through the temporal bones of the capybara's skull, breaking its zygomatic arch and mandible and penetrating its brain, often through the ears.[55] This may be an adaptation to "cracking open" turtle shells; armored reptiles may have formed an abundant prey base for the jaguar following the late Pleistocene extinctions.[54] It has been reported that an individual jaguar can drag an 360 kg (800 lb) bull 8 m (25 ft) in its jaws and pulverize the heaviest bones.[56]

The activity patterns of the jaguar have been found to coincide with the activity of their main prey species in their biomes.[57] Camera trap studies have shown that jaguars primarily have a crepuscular–nocturnal activity pattern in all the biomes that they are found in; however jaguars have been recorded to have considerable diurnal activity in thickly forested regions of the Amazon Rainforest and the Pantanal, as well as purely nocturnal activity in other regions such as the Atlantic forest.[58]

The jaguar is a stalk-and-ambush rather than a chase predator. The cat will walk slowly down forest paths, listening for and stalking prey before rushing or ambushing. The jaguar attacks from cover and usually from a target's blind spot with a quick pounce; the species' ambushing abilities are considered nearly peerless in the animal kingdom by both indigenous people and field researchers, and are probably a product of its role as an apex predator in several different environments.[59] The ambush may include leaping into water after prey, as a jaguar is quite capable of carrying a large kill while swimming; its strength is such that carcasses as large as a heifer can be hauled up a tree to avoid flood levels. After killing prey, the jaguar will drag the carcass to a thicket or other secluded spot. It begins eating at the neck and chest, rather than the midsection. The heart and lungs are consumed, followed by the shoulders.[59]

The daily food requirement of a 34 kg (75 lb) animal, at the extreme low end of the species' weight range, has been estimated at 1.4 kg (3 lb).[60] For captive animals in the 50–60 kg (110–130 lb) range, more than 2 kg (4 lb) of meat daily are recommended.[61] In the wild, consumption is naturally more erratic; wild cats expend considerable energy in the capture and kill of prey, and they may consume up to 25 kg (55 lb) of meat at one feeding, followed by periods of famine.[62] Though carnivorous, there is evidence that wild jaguars consume the roots of Banisteriopsis caapi.[63]

Reproduction and life cycle

Jaguar females reach sexual maturity at about two years of age, and males at three or four. The cat probably mates throughout the year in the wild, with births increasing when prey is plentiful.[64] Research on captive male jaguars supports the year-round mating hypothesis, with no seasonal variation in semen traits and ejaculatory quality; low reproductive success has also been observed in captivity.[65] Generation length of the jaguar is 9.8 years.[66]

Female estrus is 6–17 days out of a full 37-day cycle, and females will advertise fertility with urinary scent marks and increased vocalization.[64] Females range more widely than usual during courtship. Pairs separate after mating, and females provide all parenting. The gestation period lasts 93–105 days; females give birth to up to four cubs, and most commonly to two. The mother will not tolerate the presence of males after the birth of cubs, given a risk of infanticide; this behavior is also found in the tiger.[59]

The young are born blind, gaining sight after two weeks. Cubs are weaned at three months, but remain in the birth den for six months before leaving to accompany their mother on hunts.[67] They will continue in their mother's company for one to two years before leaving to establish a territory for themselves. Young males are at first nomadic, jostling with their older counterparts until they succeed in claiming a territory. Typical lifespan in the wild is estimated at around 12–15 years; in captivity, the jaguar lives up to 23 years, placing it among the longest-lived cats.[68]

Social activity

Like most cats, the jaguar is solitary outside mother–cub groups. Adults generally meet only to court and mate (though limited noncourting socialization has been observed anecdotally[59]) and carve out large territories for themselves. Female territories, which range from 25 to 40 km2 in size, may overlap, but the animals generally avoid one another. Male ranges cover roughly twice as much area, varying in size with the availability of game and space, and do not overlap. The territory of a male can contain those of several females.[59][69] The jaguar uses scrape marks, urine, and feces to mark its territory.[70][71]

Like the other big cats except the snow leopard, the jaguar is capable of roaring[72][73] and does so to warn territorial and mating competitors away; intensive bouts of counter-calling between individuals have been observed in the wild.[54] Their roar often resembles a repetitive cough, and they may also vocalize mews and grunts.[68] Mating fights between males occur, but are rare, and aggression avoidance behavior has been observed in the wild.[70] When it occurs, conflict is typically over territory: a male's range may encompass that of two or three females, and he will not tolerate intrusions by other adult males.[59]

The jaguar is often described as nocturnal, but is more specifically crepuscular (peak activity around dawn and dusk). Both sexes hunt, but males travel farther each day than females, befitting their larger territories. The jaguar may hunt during the day if game is available and is a relatively energetic feline, spending as much as 50–60 percent of its time active.[28] The jaguar's elusive nature and the inaccessibility of much of its preferred habitat make it a difficult animal to sight, let alone study.

Attacks on humans

Jaguars did not evolve eating large primates and do not normally see man as food.[74] Experts have cited them as the least likely of all big cats to kill and eat man and the majority of attacks come when it has been cornered or wounded.[75] However, such behavior appears to be more frequent where humans enter jaguar habitat and decrease prey.[76] Captive jaguars sometimes attack zookeepers.[77] When the conquistadors arrived in the Americas, they feared jaguars. Nevertheless, even in those times, the jaguar's chief prey was the capybara in South America and peccary further north. Charles Darwin reported a saying of Indigenous peoples of the Americas that people would not have to fear the jaguar as long as capybaras were abundant.[78]

Threats

Jaguar populations are rapidly declining. The species is listed as Near Threatened on the IUCN Red List. The loss of parts of its range, including its virtual elimination from its historic northern areas and the increasing fragmentation of the remaining range, have contributed to this status.[1] Particularly significant declines occurred in the 1960s, when more than 15,000 jaguars were killed for their skins in the Brazilian Amazon yearly; the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of 1973 brought about a sharp decline in the pelt trade.[79] Detailed work performed under the auspices of the Wildlife Conservation Society revealed the species has lost 37% of its historic range, with its status unknown in an additional 18% of the global range. More encouragingly, the probability of long-term survival was considered high in 70% of its remaining range, particularly in the Amazon basin and the adjoining Gran Chaco and Pantanal.[80]

The major risks to the jaguar include deforestation across its habitat, increasing competition for food with human beings, especially in dry and unproductive habitat,[1][81] poaching, hurricanes in northern parts of its range, and the behavior of ranchers who will often kill the cat where it preys on livestock. When adapted to the prey, the jaguar has been shown to take cattle as a large portion of its diet; while land clearance for grazing is a problem for the species, the jaguar population may have increased when cattle were first introduced to South America, as the animals took advantage of the new prey base. This willingness to take livestock has induced ranch owners to hire full-time jaguar hunters.[68]

The skins of wild cats and other mammals have been highly valued by the fur trade for many decades. From the beginning of the 20th-century Jaguars were hunted in large numbers, but over-harvest and habitat destruction reduced the availability and induced hunters and traders to gradually shift to smaller species by the 1960s. The international trade of jaguar skins had its largest boom between the end of the Second World War and the early 1970, due to the growing economy and lack of regulations. From 1967 onwards, the regulations introduced by national laws and international agreements diminished the reported international trade from as high as 13000 skins in 1967, through 7000 skins in 1969, until it became negligible after 1976, although illegal trade and smuggling continue to be a problem. During this period, the biggest exporters were Brazil and Paraguay, and the biggest importers were the US and Germany.[82]

Conservation

The jaguar is listed on CITES Appendix I, which means that all international trade in jaguars or their body parts is prohibited. Hunting jaguars is prohibited in Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, French Guiana, Honduras, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Suriname, the United States, and Venezuela. Hunting jaguars is restricted in Guatemala and Peru.[1] Trophy hunting is still permitted in Bolivia, and it is not protected in Ecuador or Guyana.[83]

Jaguar Conservation Units

Jaguar conservation is complicated because of the species' large range spanning 18 countries with different policies and regulations. Specific areas of high importance for jaguar conservation, so-called "Jaguar Conservation Units" (JCU) were determined in 2000. These are large areas inhabited by at least 50 jaguars. Each unit was assessed and evaluated on the basis of size, connectivity, habitat quality for both jaguar and prey, and jaguar population status. That way, 51 Jaguar Conservation Units were determined in 36 geographic regions as priority areas for jaguar conservation including:[80]

- the Sierra Madre of Mexico

- the Selva Maya tropical forests extending over Mexico, Belize, and Guatemala

- the Chocó-Darién moist forests from Honduras, Panama to Colombia

- Sierra de Tamaulipas

- Venezuelan Llanos

- northern Cerrado and Amazon basin in Brazil

- Misiones Province in Argentina

Recent studies underlined that to maintain the robust exchange across the jaguar gene pool necessary for maintaining the species, it is important that jaguar habitats are interconnected. To facilitate this, a new project, the Paseo del Jaguar, has been established to connect several jaguar hotspots.[84]

In 1986, the Cockscomb Basin Wildlife Sanctuary was established in Belize as the world's first protected area for jaguar conservation.[85]

Given the inaccessibility of much of the species' range, particularly the central Amazon, estimating jaguar numbers is difficult. Researchers typically focus on particular bioregions, thus species-wide analysis is scant. In 1991, 600–1,000 (the highest total) were estimated to be living in Belize. A year earlier, 125–180 jaguars were estimated to be living in Mexico's 4,000-km2 (2400-mi2) Calakmul Biosphere Reserve, with another 350 in the state of Chiapas. The adjoining Maya Biosphere Reserve in Guatemala, with an area measuring 15,000 km2 (9,000 mi2), may have 465–550 animals.[86] Work employing GPS telemetry in 2003 and 2004 found densities of only six to seven jaguars per 100 km2 in the critical Pantanal region, compared with 10 to 11 using traditional methods; this suggests the widely used sampling methods may inflate the actual numbers of cats.[87]

Approaches

In setting up protected reserves, efforts generally also have to be focused on the surrounding areas, as jaguars are unlikely to confine themselves to the bounds of a reservation, especially if the population is increasing in size. Human attitudes in the areas surrounding reserves and laws and regulations to prevent poaching are essential to make conservation areas effective.[88]

To estimate population sizes within specific areas and to keep track of individual jaguars, camera trapping and wildlife tracking telemetry are widely used, and feces may be sought out with the help of detector dogs to study jaguar health and diet.[87][89] Current conservation efforts often focus on educating ranch owners and promoting ecotourism.[90] The jaguar is generally defined as an umbrella species – its home range and habitat requirements are sufficiently broad that, if protected, numerous other species of smaller range will also be protected.[91] Umbrella species serve as "mobile links" at the landscape scale, in the jaguar's case through predation. Conservation organizations may thus focus on providing viable, connected habitat for the jaguar, with the knowledge other species will also benefit.[90]

Ecotourism setups are being used to generate public interest in charismatic animals such as the jaguar, while at the same time generating revenue that can be used in conservation efforts. Audits done in Africa have shown that ecotourism has helped in African cat conservation. As with large African cats, a key concern in jaguar ecotourism is the considerable habitat space the species requires, so if ecotourism is used to aid in jaguar conservation, some considerations need to be made as to how existing ecosystems will be kept intact, or how new ecosystems that are large enough to support a growing jaguar population will be put into place.[92]

In culture and mythology

A conch shell gorget depicting a jaguar was found in a burial mound in Benton County, Missouri. The gorget shows evenly-engraved lines and measures 104 mm × 98 mm (4.1 in × 3.9 in).[25] Rock drawings made by the Hopi, Anasazi and Pueblo all over the desert and chaparral regions of the American Southwest show an explicitly spotted cat, presumably a jaguar, as it is drawn much larger than an ocelot.[46]

Pre-Columbian Americas

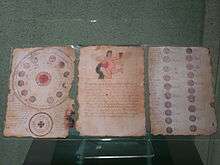

In pre-Columbian Central and South America, the jaguar was a symbol of power and strength. In the Andes, a jaguar cult disseminated by the early Chavín culture became accepted over most of today's Peru by 900 BC. The later Moche culture of northern Peru used the jaguar as a symbol of power in many of their ceramics.[97][98][99] In the religion of the Muisca, who inhabited the cool Altiplano Cundiboyacense in the Colombian Andes, the jaguar was considered a sacred animal and during their religious rituals the people dressed in jaguar skins.[100] The skins were traded with the lowland peoples of the tropical Orinoquía Region.[101] The name of zipa Nemequene was derived from the Muysccubun words nymy and quyne, meaning "force of the jaguar".[102][103]

In Mesoamerica, the Olmec—an early and influential culture of the Gulf Coast of Mexico roughly contemporaneous with the Chavín—developed a distinct "Olmec were-jaguar" motif of sculptures and figurines showing stylised jaguars or humans with jaguar characteristics. In the later Maya civilization, the jaguar was believed to facilitate communication between the living and the dead and to protect the royal household. The Maya saw these powerful felines as their companions in the spiritual world, and a number of Maya rulers bore names that incorporated the Mayan word for jaguar (b'alam in many of the Mayan languages). Balam (Jaguar) remains a common Maya surname, and it is also the name of Chilam Balam, a legendary author to whom are attributed 17th and 18th-centuries Maya miscellanies preserving much important knowledge. The Aztec civilization shared this image of the jaguar as the representative of the ruler and as a warrior. The Aztecs formed an elite warrior class known as the Jaguar warrior. In Aztec mythology, the jaguar was considered to be the totem animal of the powerful deity Tezcatlipoca.[59][104] Remains of jaguar bones were discovered in a burial site in Guatemala which indicates that Mayans kept jaguars as pets.[105]

Contemporary culture

The jaguar and its name are widely used as a symbol in contemporary culture. It is the national animal of Guyana, and is featured in its Coat of arms of Guyana.[106] The flag of the Department of Amazonas features a black jaguar silhouette pouncing towards a hunter.[107] The jaguar also appears in banknotes of the Brazilian real. The jaguar is also a common fixture in the mythology of several native cultures in South America.[108]

The crest of the Argentine Rugby Union features a jaguar; however, the Argentina national rugby union team is nicknamed Los Pumas.[109] In the spirit of the ancient Mayan culture, the 1968 Summer Olympics in Mexico City adopted a red jaguar as the first official Olympic mascot.[110] Jaguar is widely used as a product name, most prominently for the Jaguar car. The name has been adopted by sports franchises, including the National Football League's Jacksonville Jaguars and the Mexican association football club Chiapas F.C.

See also

References

- Quigley, H.; Foster, R.; Petracca, L.; Payan, E.; Salom, R. & Harmsen, B. (2017). "Panthera onca". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2017: e.T15953A123791436.

- Marcgraf, G. (1648). "Iaguara Brasiliensibus". Historia Naturalis Brasiliae. Auspicio et Beneficio. Historia Rerum Naturalium Brasiliae. Lugdun Batavorum, Amstelodam: Franciscus Hackius et Lud. Elzevirius. p. 235.

- Ray, J. (1693). "Pardus an Lynx brasiliensis, Jaguara". Synopsis Methodica Animalium Quadrupedum et Serpentini Generis. Vulgarium Notas Characteristicas, Rariorum Descriptiones integras exhibens. London: S. Smith & B. Walford. p. 168.

- Labat, J.B. (1731). "Once, espèce de Tigre". Voyage du chevalier Des Marchais en Guinée, isles voisines, et à Cayenne, fait en 1725, 1726 & 1727. Tome III. Amsterdam: La Compagnie. p. 285.

- Liddell, H. G. & Scott, R. (1940). "πάνθηρ". A Greek-English Lexicon (Revised and augmented ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Linnaeus, C. (1758). "Felis onca". Systema naturæ per regna tria naturæ, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis (in Latin). Tomus I (Decima, reformata ed.). Holmiae: Laurentius Salvius. p. 42.

- Wozencraft, W.C. (2005). "Species Panthera onca". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 546–547. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- Pocock, R. I. (1939). "The races of jaguar (Panthera onca)". Novitates Zoologicae. 41: 406–422.

- Seymour, K. L. (1989). "Panthera onca" (PDF). Mammalian Species. 340 (340): 1–9. doi:10.2307/3504096. JSTOR 3504096. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 June 2010. Retrieved 27 December 2009.

- Blainville, H. M. D. de (1843). "F. leo nubicus". Ostéographie ou description iconographique comparée du squelette et du système dentaire des mammifères récents et fossils pour servir de base à la zoologie et la géologie (in French). Tome II. Paris: J. B. Baillière et Fils. p. Plate VIII.

- Gray, J. E. (1857). "Notice of a new species of jaguar from Mazatlan, living in the gardens of the Zoological Society". Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London. 25: 278.

- Ameghino, F. (1888). "Formación Pampeana". Los Mamíferos fósiles de la República Argentina (in Spanish). Buenos Aires: Pablo E. Coni é hijos. p. 473–493.

- Mearns, E. A. (1901). "The American Jaguars". Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington. 14: 137–143.

- Hollister, N. (1915). "Two new South American jaguars". Proceedings of the United States National Museum. 48: 169–170.

- Goldman, E. A. (1932). "The jaguars of North America". Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington. 45: 143–146.

- Nelson, E. W. & Goldman, E. A. (1933). "Revision of the jaguars". Journal of Mammalogy. 14 (3): 221–240. JSTOR 1373821.

- Eizirik, E.; Kim, J. H.; Menotti-Raymond, M.; Crawshaw P. G. Jr.; O'Brien, S. J. & Johnson, W. E. (2001). "Phylogeography, population history and conservation genetics of jaguars (Panthera onca, Mammalia, Felidae)". Molecular Ecology. 10 (1): 65–79. doi:10.1046/j.1365-294X.2001.01144.x. PMID 11251788.

- Larson, S. E. (1997). "Taxonomic re-evaluation of the jaguar". Zoo Biology. 16 (2): 107–120. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1098-2361(1997)16:2<107::AID-ZOO2>3.0.CO;2-E.

- Ruiz-Garcia, M.; Payan, E.; Murillo, A. & Alvarez, D. (2006). "DNA microsatellite characterization of the jaguar (Panthera onca) in Colombia". Genes & Genetic Systems. 81 (2): 115–127. doi:10.1266/ggs.81.115. PMID 16755135.

- Kitchener, A. C.; Breitenmoser-Würsten, C.; Eizirik, E.; Gentry, A.; Werdelin, L.; Wilting, A.; Yamaguchi, N.; Abramov, A. V.; Christiansen, P.; Driscoll, C.; Duckworth, J. W.; Johnson, W.; Luo, S.-J.; Meijaard, E.; O'Donoghue, P.; Sanderson, J.; Seymour, K.; Bruford, M.; Groves, C.; Hoffmann, M.; Nowell, K.; Timmons, Z. & Tobe, S. (2017). "A revised taxonomy of the Felidae: The final report of the Cat Classification Task Force of the IUCN Cat Specialist Group" (PDF). Cat News. Special Issue 11: 70–71.

- Johnson, W. E.; Eizirik, E.; Pecon-Slattery, J.; Murphy, W. J.; Antunes, A.; Teeling, E. & O'Brien, S. J. (2006). "The Late Miocene radiation of modern Felidae: A genetic assessment". Science. 311 (5757): 73–77. Bibcode:2006Sci...311...73J. doi:10.1126/science.1122277. PMID 16400146.

- Janczewski, D. N.; Modi, W. S.; Stephens, J. C. & O'Brien, S. J. (1996). "Molecular evolution of mitochondrial 12S RNA and cytochrome b sequences in the pantherine lineage of Felidae". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 12 (4): 690–707. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040232. PMID 7544865.

- Johnson, W. E. & O'Brien, S. J. (1997). "Phylogenetic reconstruction of the Felidae using 16S rRNA and NADH-5 mitochondrial genes". Journal of Molecular Evolution. 44 (S1): S98–S116. Bibcode:1997JMolE..44S..98J. doi:10.1007/PL00000060. PMID 9071018.

- Yu, L. & Zhang, Y. P. (2005). "Phylogenetic studies of pantherine cats (Felidae) based on multiple genes, with novel application of nuclear beta-fibrinogen intron 7 to carnivores". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 35 (2): 483–495. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2005.01.017. PMID 15804417.

- Daggett, P. M. & Henning, D. R. (1974). "The Jaguar in North America". American Antiquity. 39 (3): 465–469. JSTOR 279437.

- Hayward, M. W.; Kamler, J. F.; Montgomery, R. A. & Newlove, A. (2016). "Prey Preferences of the Jaguar Panthera onca Reflect the Post-Pleistocene Demise of Large Prey". Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution. 3: 148. doi:10.3389/fevo.2015.00148.

- Hope, M. K. & Deem, S. L. (2006). "Retrospective Study of Morbidity and Mortality of Captive Jaguars (Panthera onca) in North America: 1982–2002" (PDF). Zoo Biology. 25 (6): 501–512. doi:10.1002/zoo.20112.

- Nowell, K. & Jackson, P. (1996). "Jaguar, Panthera onca (Linnaeus, 1758)" (PDF). Wild Cats. Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN/SSC Cat Specialist Group. pp. 118–122.

- Nowak, R.M. (1999). Walker's Mammals of the World. 2. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 831. ISBN 978-0-8018-5789-8.

- Burnie, D. & Wilson, D.E. (2001). Animal: The Definitive Visual Guide to the World's Wildlife. New York City: Dorling Kindersley. ISBN 978-0-7894-7764-4.

- Boitani, L. (1984). Simon and Schuster's Guide to Mammals. New York: Touchstone. ISBN 978-0-671-43727-5.

- "All about Jaguars: Ecology". Wildlife Conservation Society. Archived from the original on 29 May 2009. Retrieved 11 August 2006.

- Nuanaez, R.; Miller, B. & Lindzey, F. (2000). "Food habits of jaguars and pumas in Jalisco, Mexico". Journal of Zoology. 252 (3): 373–379. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.2000.tb00632.x.

- Wroe, S.; McHenry, C. & Thomason, J. (2006). "Bite club: comparative bite force in big biting mammals and the prediction of predatory behavior in fossil taxa" (PDF). Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 272 (1563): 619–25. PMC 1564077. PMID 15817436.

- Hartstone-Rose, A.; Perry, J. M. G. & Morrow, C. J. (2012). "Bite Force Estimation and the Fiber Architecture of Felid Masticatory Muscles". The Anatomical Record: Advances in Integrative Anatomy and Evolutionary Biology. 295 (8): 1336–1351. doi:10.1002/ar.22518. PMID 22707481.

- Christiansen, P. (2007). "Canine morphology in the larger Felidae: implications for feeding ecology". Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 91 (4): 573–592. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8312.2007.00819.x.

- Gonyea, W.J. (1976). "Adaptive differences in the body proportions of large felids". Acta Anatomica. 96 (1): 81–96. doi:10.1159/000144663.

- Brown, D.E. & Lopez-Gonzalez, C.A. (2001). Borderland jaguars: tigres de la frontera. Salt Lake City, UT: University of Utah Press.

- Eizirik, E.; Yuhki, N.; Johnson, W. E.; Menotti-Raymond, M.; Hannah, S. S. & O'Brien, S. J. (2003). "Molecular Genetics and Evolution of Melanism in the Cat Family". Current Biology. 13 (5): 448–453. doi:10.1016/S0960-9822(03)00128-3. PMID 12620197.

- Dinets, V. & Polechla, P. J. (2005). "First documentation of melanism in the jaguar (Panthera onca) from northern Mexico". Cat News. 42: 18. Archived from the original on 26 September 2006.

- Núñez, M.C. & Jiménez, E.C. (2009). "A new record of a black jaguar, Panthera onca (Carnivora: Felidae) in Costa Rica" (PDF). Brenesia. 71: 67–68.

- Mooring, M. S.; Eppert, A. A. & Botts, R. T. (2020). "Natural Selection of Melanism in Costa Rican Jaguar and Oncilla: A Test of Gloger's Rule and the Temporal Segregation Hypothesis". Tropical Conservation Science. 13: 1–15. doi:10.1177/1940082920910364.

- "Jaguars". The Midwestern United States 16,000 years ago. Illinois State Museum. Retrieved 20 August 2006.

- Merriam, C.H. (1919). "Is the Jaguar entitled to a place in the Californian fauna?". Journal of Mammalogy. 1 (1): 38–42. doi:10.1093/jmammal/1.1.38.

- Brulliard, K. (2016). "Jaguar spotting: A new wild cat may be roaming the United States". The Washington Post. Retrieved 21 May 2017.

- Pavlik, S. (2003). "Rohonas and Spotted Lions: The Historical and Cultural Occurrence of the Jaguar, Panthera onca, among the Native Tribes of the American Southwest". Wicazo Sa Review. 18 (1): 157–175. doi:10.1353/wic.2003.0006. JSTOR 1409436.

- "Jaguar (Panthera Onca)" (PDF). Phoenix Zoo. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 December 2014. Retrieved 30 August 2006.

- "Structure and Character: Keystone Species". Mongabay. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 30 August 2006.

- Wright, S. J.; Gompper, M. E.; DeLeon, B. (1994). "Are large predators keystone species in Neotropical forests? The evidence from Barro Colorado Island". Oikos. 71 (2): 279–294. doi:10.2307/3546277. JSTOR 3546277. Retrieved 11 November 2011.

- Iriarte, J. A.; Franklin, W.L.; Johnson, W.E. & Redford, K.H. (1990). "Biogeographic variation of food habits and body size of the America puma". Oecologia. 85 (2): 185–190. Bibcode:1990Oecol..85..185I. doi:10.1007/BF00319400. PMID 28312554.

- Gutiérrez-González, Carmina E.; López-González, Carlos A. (18 January 2017). "Jaguar interactions with pumas and prey at the northern edge of jaguars' range". PeerJ. 5: e2886. doi:10.7717/peerj.2886. PMC 5248577. PMID 28133569.

- Otfinoski, Steven (2010). Jaguars. Marshall Cavendish. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-7614-4839-6. Retrieved 16 March 2011.

- "Jaguar". Kids' Planet. Defenders of Wildlife. Archived from the original on 30 September 2006. Retrieved 23 September 2006.

- Emmons, L.H. (1987). "Comparative feeding ecology of fields in a neotropical rain forest". Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 20 (4): 271–283. doi:10.1007/BF00292180.

- Schaller, G.B. & Vasconselos, J.M.C. (1978). "Jaguar predation on capybara" (PDF). Zeitschrift für Säugetierkunde. 43: 296–301.

- McGrath, S. (2004). "Top Cat". Audubon. National Audubon Society. Archived from the original on 4 July 2008. Retrieved 2 December 2009.

- Harmsen, B.J.; Foster, R.J.; Silver, S. C.; Ostro, L.E.T. & Doncaster, C.P. (2011). "Jaguar and puma activity patterns in relation to their main prey". Mammalian Biology – Zeitschrift für Säugetierkunde. 76 (3): 320–324. doi:10.1016/j.mambio.2010.08.007.

- Astete, S.R.; Sollmann, R. & Silveira, L. (2008). "Comparative ecology of jaguars in Brazil". Cat News (Special Issue 4): 9–14. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.528.3603.

- Baker, Natural History and Behavior, pp. 8–16.

- "Determination That Designation of Critical Habitat Is Not Prudent for the Jaguar". Federal Register Environmental Documents. 12 July 2006. Retrieved 30 August 2006.

- Baker, Hand-rearing, pp. 62–75 (table 5).

- Baker, Nutrition, pp. 55–61.

- Rood, R. (2011). "Reassessing the Cultural and Psychopharmacological Significance of Banisteriopsis caapi: Preparation, Classification and Use Among the Piaroa of Southern Venezuela". Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 40 (3): 301–307. doi:10.1080/02791072.2008.10400645. PMID 19004422.

- Baker, Reproduction, pp. 28–38.

- Morato, R. G.; Vaz Guimaraes, M; A; B.; Ferriera, F.; Nascimento Verreschi, I. T.; Renato Campanarut Barnabe (1999). "Reproductive characteristics of captive male jaguars". Brazilian Journal of Veterinary Research and Animal Science. 36 (5): 00. doi:10.1590/S1413-95961999000500008. Retrieved 11 November 2011.

- Pacifici, M.; Santini, L.; Di Marco, M.; Baisero, D.; Francucci, L.; Grottolo Marasini, G.; Visconti, P.; Rondinini, C. (2013). "Generation length for mammals". Nature Conservation. 5 (5): 87–94. doi:10.3897/natureconservation.5.5734.

- Jeff Egerton (Spring 2006). "Jaguars: Magnificence in the Southwest" (PDF). Newsletter. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 6 December 2009.

- "Jaguar Fact Sheet". Jaguar Species Survival Plan. American Zoo and Aquarium Association. Archived from the original on 27 January 2012. Retrieved 14 August 2006.

- Schaller, George B. & Crawshaw, P.G. Jr. (1980). "Movement Patterns of Jaguar". Biotropica. 12 (3): 161–168. doi:10.2307/2387967. JSTOR 2387967.

- Rabinowitz, A. R. & Nottingham, B.G. Jr. (1986). "Ecology and behaviour of the Jaguar (Panthera onca) in Belize, Central America". Journal of Zoology. 210 (1): 149–159. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1986.tb03627.x.

- Harmsen, Bart J.; Foster, R.J.; Gutierrez, S.M.; Marin, S.Y. & Doncaster, C.P. (2007). "Scrape-marking behavior of jaguars (Panthera onca) and pumas (Puma concolor)". Journal of Mammalogy. 91 (5): 1225–1234. doi:10.1644/09-mamm-a-416.1.

- Weissengruber, G. E.; Forstenpointner, G.; Peters, G.; Kübber-Heiss, A.; Fitch, W. T. (2002). "Hyoid apparatus and pharynx in the lion (Panthera leo), jaguar (Panthera onca), tiger (Panthera tigris), cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus) and domestic cat (Felis silvestris f. catus)". Journal of Anatomy. 201 (3): 195–209. doi:10.1046/j.1469-7580.2002.00088.x. PMC 1570911. PMID 12363272.

- Hast, M. H. (1989). "The larynx of roaring and non-roaring cats". Journal of Anatomy. 163: 117–121. PMC 1256521. PMID 2606766.

- "Why did Audubon Zoo's escaped jaguar kill so many animals?".

- Seidensticker, J.; Lumpkin, S. (2016). Cats in Question: The Smithsonian Answer Book. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution. ISBN 9781588345462.

- V. Iserson, K.; Francis, Adama M. (2015). "Jaguar Attack on a Child: Case Report and Literature Review". Western Journal of Emergency Medicine. 16 (2): 303–309. doi:10.5811/westjem.2015.1.24043. PMC 4380383. PMID 25834674.

- "Jaguar: The Western Hemisphere's Top Cat". Planeta. February 2008. Archived from the original on 21 August 2008. Retrieved 8 March 2009.

- Porter, J. H. (1894). "The Jaguar". Wild beasts; a study of the characters and habits of the elephant, lion, leopard, panther, jaguar, tiger, puma, wolf, and grizzly bear. New York: C. Scribner's sons. pp. 174–195.

- Weber, W. & Rabinowitz, A. (1996). "A Global Perspective on Large Carnivore Conservation" (PDF). Conservation Biology. 10 (4): 1046–1054.

- Sanderson, E. W.; K. H., Redford; Chetkiewicz, C. B.; Medellin, R. A.; Rabinowitz, A. R.; Robinson, J. G.; Taber, A. B. (2002). "Planning to save a species: the jaguar as a model". Conservation Biology. 16 (1): 58–72. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1739.2002.00352.x.

- Jędrzejewski, W.; Boede, E. O.; Abarca, M.; Sánchez-Mercado, A.; Ferrer-Paris, J. R.; Lampo, M.; Velásquez, G.; Carreño, R.; Viloria, Á. L.; Hoogesteijn, R.; Robinson, H. S.; Stachowicz, I.; Cerda, H.; Weisz, M. del Mar; Barros, T. R.; Rivas, Gilson A.; Borges, G.; Molinari, J.; Lew, D.; Takiff, H.; Schmidt, K. (2017). "Predicting carnivore distribution and extirpation rate based on human impacts and productivity factors; assessment of the state of jaguar (Panthera onca) in Venezuela". Biological Conservation. 206: 132–142. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2016.09.027.

- Broad, S. (1987). The harvest of and trade in Latin American spotted cats (Felidae) and otters (Lutrinae). Cambridge, UK: IUCN Conservation Monitoring Centre. Retrieved 8 July 2016.

- Baker, W. K. Jr.; et al. Law, Christopher (ed.). Guidelines for Captive Management of Jaguars (PDF). Jaguar Species Survival Plan. American Zoo and Aquarium Association. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 January 2012. Retrieved 11 November 2011.

- "Path of the jaguars project". Ngm.nationalgeographic.com. March 2009. Retrieved 2 April 2010.

- Weckel, M., Giuliano, W. and Silver, S. (2006). "Cockscomb revisited: jaguar diet in the Cockscomb Basin Wildlife Sanctuary, Belize". Biotropica. 38 (5): 687–690. doi:10.1111/j.1744-7429.2006.00190.x.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Baker, Protection and Population Status, p. 4.

- Soisalo, M. K. & Cavalcanti, S. M.C. (2006). "Estimating the density of a Jaguar population in the Brazilian Pantanal using camera-traps and capture-recapture sampling in combination with GPS radio-telemetry" (PDF). Biological Conservation. 129 (4): 487–496. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2005.11.023.

- Gutierrez-Gonzalez, C.E.; Gomez-Ramirez, M.A.; Lopez-Gonzalez, C.A. & Doherty, P.F. (2015). "Are Private Reserves Effective for Jaguar Conservation?". PLOS ONE. 10 (9): e0137541. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1037541G. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0137541. PMC 4580466. PMID 26398115.

- Furtado, M. M.; Carrillo-Percastegui, S. E.; Jácomo, A. T. A.; Powell, G.; Silveira, L.; Vynne, C. & Sollmann, R. (2008). "Studying jaguars in the wild: past experiences and future perspectives" (PDF). Cat News (Special Issue 4).

- "Jaguar Refuge in the Llanos Ecoregion". World Wildlife Fund. Archived from the original on 17 December 2014. Retrieved 1 September 2006.

- "Glossary". Sonoran Desert Conservation Plan: Kids. Pima County Government. Archived from the original on 20 June 2006. Retrieved 1 September 2006.

- Mossaz, A.; Buckley, R.C. & Castley, J.G. (2015). "Ecotourism Contributions to Conservation of African Big Cats". Journal for Nature Conservation. 28: 112–118. doi:10.1016/j.jnc.2015.09.009. hdl:10072/125191.

- Brown, D.E. & González, C.A.L. (2000). "Notes on the occurrences of jaguars in Arizona and New Mexico". The Southwestern Naturalist. 45 (4): 537–542. JSTOR 3672607.

- Lamberton-Moreno, J. (2015). "Student project results in new jaguar sighting". Sky Island Alliance. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- Handwerk, B. (2016). "Only known Jaguar in U.S. filmed in rare video". National Geographic News. Retrieved 4 February 2016.

- Greenberg, S. H. (2012). "Kitty Corner: Jaguars Win Critical Habitat in U.S." Scientific American.

- Museo Arqueologico Rafael Larco Herrera (1997). Berrin, K.; Benson, E. P. (eds.). The Spirit of Ancient Peru: Treasures from the Museo Arqueologico Rafael Larco Herrera. London, New York, Melbourne, Singapore, Hong Kong: Thames and Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-01802-6.

- Bulliet, R. W. (2000). The Earth and Its Peoples: A Global History. Houghton Mifflin. pp. 75–. ISBN 978-1-4390-8476-2.

- Lockard, C. A. (2010). Societies, Networks, and Transitions. A Global History. To 1500 (Second ed.). Boston: Wadsworth Cengage Learning. pp. 215–. ISBN 978-1-4390-8535-6.

- Ocampo López, J. (2007). Grandes culturas indígenas de América – Great indigenous cultures of the Americas (in Spanish). Bogotá, Colombia: Plaza & Janes Editores Colombia S.A. p. 231. ISBN 978-958-14-0368-4.

- Kruschek, M. H. (2003). The evolution of the Bogotá chiefdom: A household view (PDF) (PhD). Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh.

- "nymy" (in Spanish). Muysccubun Dictionary Online. Retrieved 11 January 2017.

- "quyne" (in Spanish). Muysccubun Dictionary Online. Retrieved 11 January 2017.

- Christenson, A.J. (2007). Popol Vuh: The Sacred Book of the Maya. Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. p. 196. ISBN 978-0-8061-3839-8. Retrieved 11 December 2011.

- "Ancient Mayans Probably Kept Jaguars As Pets And Raised Dogs For Food". IFLScience. 2018. Retrieved 26 July 2017.

- "Guyana". RBC Radio. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 11 November 2011.

- Gutterman, D. (26 July 2008). "Amazonas Department (Colombia)". Flag of the World. Archived from the original on 5 August 2011. Retrieved 2 April 2010.

- Levi-Strauss, Claude (2004) [1964]. O Cru e o Cozido. São Paulo: Cosac & Naify. Retrieved 11 November 2011.

- Davies, S. (2007). "Puma power: Argentinian rugby". BBC News. Retrieved 8 October 2007.

- Welch, P. Cute Little Creatures: Mascots Lend a Smile to the Games (PDF). la84foundation.org. Retrieved 11 November 2011.

Bibliography

- Baker, W. K. Jr.; et al. Law, Christopher (ed.). Guidelines for Captive Management of Jaguars (PDF). Jaguar Species Survival Plan. American Zoo and Aquarium Association. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 January 2012. Retrieved 11 November 2011.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Panthera onca. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Panthera onca |

- "Jaguar Panthera onca". IUCN Cat Specialist Group.

- Sound of a jaguar roar at Vivanatura.org

- "Jaguar (Panthera onca)". Arkive. Archived from the original on 28 December 2014. Retrieved 10 February 2010.

- "Jaguar". BBC. 2014. Archived from the original on 22 September 2014.

- People and Jaguars a Guide for Coexistence

- Sky Island Alliance website

- Felidae Conservation Fund

- . Encyclopedia Americana. 1920.

- Salman the fat jaguar at Delhi Zoo, India