Mustelidae

The Mustelidae (/ˌmʌˈstɛlɪdi/;[2] from Latin mustela, weasel) are a family of carnivorous mammals, including weasels, badgers, otters, ferrets, martens, minks, and wolverines, among others. Mustelids (/ˈmʌstəlɪd/[3]) are a diverse group and form the largest family in the order Carnivora, suborder Caniformia. Mustelidae comprises about 56–60 species across eight subfamilies.[4]

| Mustelidae | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Superfamily: | Musteloidea |

| Family: | Mustelidae G. Fischer de Waldheim, 1817 |

| Type genus | |

| Mustela Linnaeus, 1758 | |

| Subfamilies | |

| |

Variety

Mustelids vary greatly in size and behaviour. The least weasel can be under a foot in length, while the giant otter of Amazonian South America can measure up to 1.7 m (5 ft 7 in) and sea otters can exceed 45 kg (99 lb) in weight. The wolverine can crush bones as thick as the femur of a moose to get at the marrow, and has been seen attempting to drive bears away from their kills. The sea otter uses rocks to break open shellfish to eat. Martens are largely arboreal, while the European badger digs extensive tunnel networks, called setts. Some mustelids have been domesticated: the ferret and the tayra are kept as pets (although the tayra requires a Dangerous Wild Animals licence in the UK), or as working animals for hunting or vermin control. Others have been important in the fur trade—the mink is often raised for its fur.

As well as being one of the most species-rich families in the order Carnivora, the family Mustelidae is one of the oldest. Mustelid-like forms first appeared about 40 million years ago, roughly coinciding with the appearance of rodents. The common ancestor of modern mustelids appeared about 18 million years ago.[4]

Characteristics

Within a large range of variation, the mustelids exhibit some common characteristics. They are typically small animals with elongated bodies, short legs, short, round ears, and thick fur.[5] Most mustelids are solitary, nocturnal animals, and are active year-round.[6]

With the exception of the sea otter,[7] they have anal scent glands that produce a strong-smelling secretion the animals use for sexual signaling and for marking territory.

Most mustelid reproduction involves embryonic diapause.[8] The embryo does not immediately implant in the uterus, but remains dormant for some time. No development takes place as long as the embryo remains unattached to the uterine lining. As a result, the normal gestation period is extended, sometimes up to a year. This allows the young to be born under more favorable environmental conditions. Reproduction has a large energy cost and it is to a female's benefit to have available food and mild weather. The young are more likely to survive if birth occurs after previous offspring have been weaned.

Mustelids are predominantly carnivorous, although some eat vegetable matter at times. While not all mustelids share an identical dentition, they all possess teeth adapted for eating flesh, including the presence of shearing carnassials. With variation between species, the most common dental formula is 3.1.3.13.1.3.2.[6]

Ecology

The fisher, tayra and martens are partially arboreal, while badgers are fossorial. A number of mustelids have aquatic lifestyles, ranging from semiaquatic minks and river otters to the fully aquatic sea otter. The sea otter is one of the few non-primate mammals known to use a tool while foraging. It uses "anvil" stones to crack open the shellfish that form a significant part of its diet. It is a "keystone species", keeping its prey populations in balance so some do not outcompete the others and destroy the kelp in which they live.

The black-footed ferret is entirely dependent on another keystone species, the prairie dog. A family of four ferrets eats 250 prairie dogs in a year; this requires a stable population of prairie dogs from an area of some 500 acres (2.0 km2).

Skunks were formerly included as a subfamily of the mustelids, but are now regarded as a separate family (Mephitidae).[9] Mongooses bear a striking resemblance to many mustelids, but belong to a distinctly different suborder—the Feliformia (all those carnivores sharing more recent origins with the cats) and not the Caniformia (those sharing more recent origins with the dogs). Because mongooses and mustelids occupy similar ecological niches, convergent evolution has led to similarity in form and behavior.

Diversity

The oldest known mustelid from North America is Corumictis wolsani from the early and late Oligocene (early and late Arikareean, Ar1–Ar3) of Oregon.[1] Middle Oligocene Mustelictis from Europe might be a mustelid as well.[1] Other early fossils of the mustelids were dated at the end of the Oligocene to the beginning of the Miocene. It is not clear which of these forms are Mustelidae ancestors and which should be considered the first mustelids.[10]

The fossil record indicates that mustelids appeared in the late Oligocene period (33 mya) in Eurasia and migrated to every continent except Antarctica and Australia (all the continents that were connected during or since the early Miocene). They reached the Americas via the Bering land bridge.

Human uses

Several mustelids, including the mink, the sable (a type of marten) and the stoat (ermine), boast exquisite and valuable furs, and have been accordingly hunted since prehistoric times. From the early Middle Ages, the trade in furs was of great economic importance for northern and eastern European nations with large native populations of fur-bearing mustelids, and was a major economic impetus behind Russian expansion into Siberia and French and English expansion in North America. In recent centuries, fur farming, notably of mink, has also become widespread and provides the majority of the fur brought to market.

One species, the sea mink (Neovison macrodon) of New England and Canada, was driven to extinction by fur trappers. Its appearance and habits are almost unknown today because no complete specimens can be found and no systematic contemporary studies were conducted.

The sea otter, which has the densest fur of any animal,[11] narrowly escaped the fate of the sea mink. The discovery of large populations in the North Pacific was the major economic driving force behind Russian expansion into Kamchatka, the Aleutian Islands, and Alaska, as well as a cause for conflict with Japan and foreign hunters in the Kuril Islands. Together with widespread hunting in California and British Columbia, the species was brought to the brink of extinction until an international moratorium came into effect in 1911.

Today, some mustelids are threatened for other reasons. Sea otters are vulnerable to oil spills and the indirect effects of overfishing; the black-footed ferret, a relative of the European polecat, suffers from the loss of American prairie; and wolverine populations are slowly declining because of habitat destruction and persecution. The rare European mink Mustela lutreola is one of the most endangered mustelid species.[12]

One mustelid, the ferret, has been domesticated and is a fairly common pet.

Systematics

The 56 living mustelids are classified into eight subfamilies in 22 genera.[4]

Phylogeny

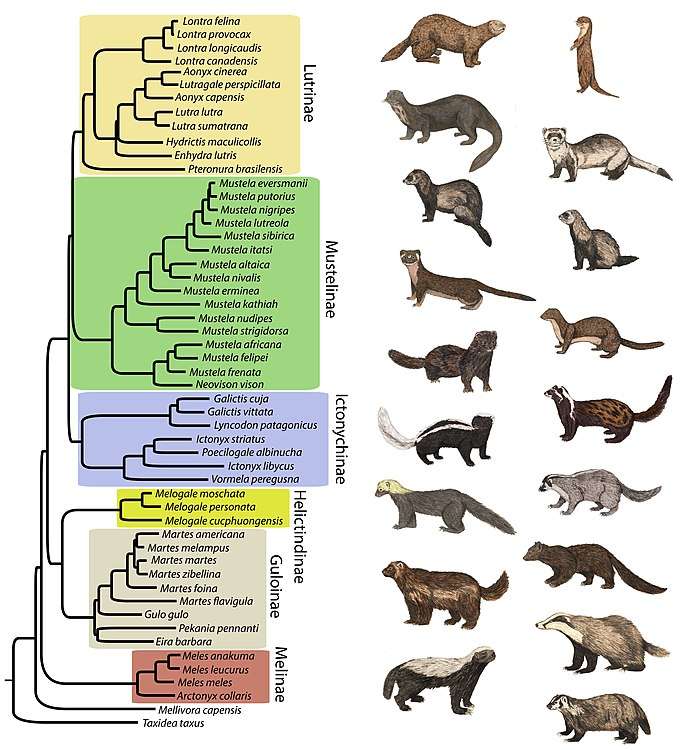

Multigene phylogenies constructed by Koepfli et al. (2008)[16] and Law et al. (2018)[4] found that Mustelidae comprises eight subfamilies. The early mustelids appear to have undergone two rapid bursts of diversification in Eurasia, with the resulting species only spreading to other continents later.[16]

Phylogenetic tree of Mustelidae. Contains 53 of the 56 putative mustelid species.[4]

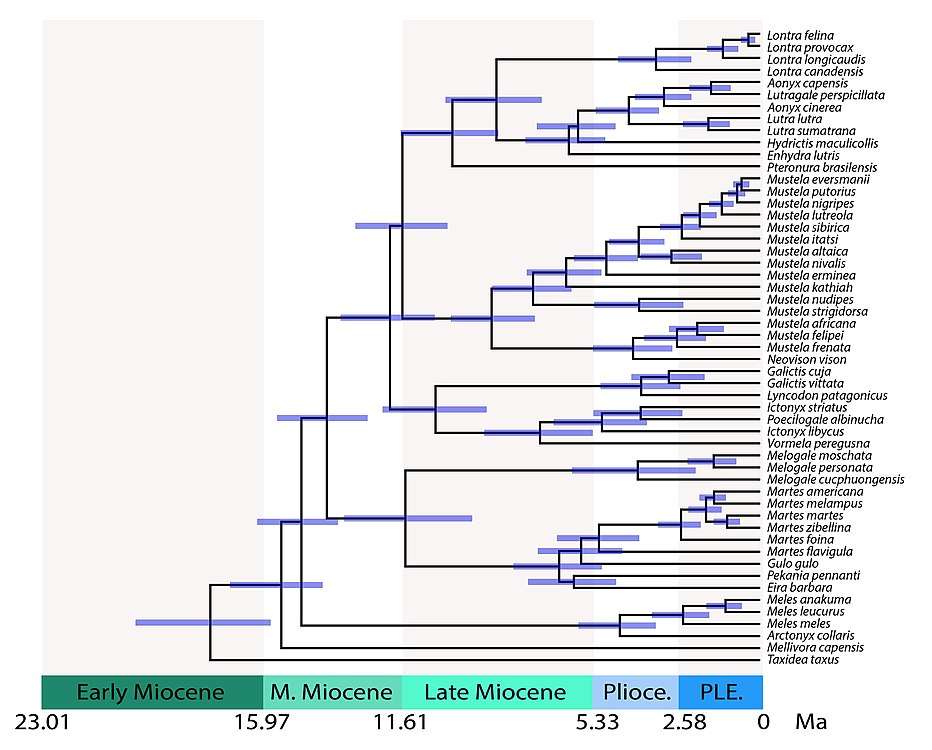

Phylogenetic tree of Mustelidae. Contains 53 of the 56 putative mustelid species.[4] Time-calibrated tree of Mustelidae showing divergence times between lineages. Split times include: 28.8 million years (Ma) for mustelids vs. procyonids; 17.8 Ma for Taxidiinae; 15.5 Ma for Mellivorinae; 14.8 Ma for Melinae; 14.0 Ma for Guloninae + Helictidinae; 11.5 Ma for Guloninae vs. Helictidinae; 12.0 Ma for Ictonychinae; 11.6 Ma for Lutrinae vs. Mustelinae.[4]

Time-calibrated tree of Mustelidae showing divergence times between lineages. Split times include: 28.8 million years (Ma) for mustelids vs. procyonids; 17.8 Ma for Taxidiinae; 15.5 Ma for Mellivorinae; 14.8 Ma for Melinae; 14.0 Ma for Guloninae + Helictidinae; 11.5 Ma for Guloninae vs. Helictidinae; 12.0 Ma for Ictonychinae; 11.6 Ma for Lutrinae vs. Mustelinae.[4]

Mustelid species diversity is often attributed to an adaptive radiation coinciding with the Mid-Miocene Climate Transition. Contrary to expectations, Law et al. (2018)[4] found no evidence for rapid bursts of lineage diversification at the origin of Mustelidae, and further analyses of lineage diversification rates using molecular and fossil-based methods did not find associations between rates of lineage diversification and Mid-Miocene Climate Transition as previously hypothesized.

See also

Notes

- Paterson, R.; Samuels, J.X.; Rybczynski, N.; Ryan, M.J.; Maddin, H.C. (2019). "The earliest mustelid in North America". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 188 (4): 1318–1339. doi:10.1093/zoolinnean/zlz091.

- "Mustelidae". Merriam-Webster Dictionary.

- "mustelid". Dictionary.com Unabridged. Random House.

- Law, C. J.; Slater, G. J.; Mehta, R. S. (2018-01-01). "Lineage Diversity and Size Disparity in Musteloidea: Testing Patterns of Adaptive Radiation Using Molecular and Fossil-Based Methods". Systematic Biology. 67 (1): 127–144. doi:10.1093/sysbio/syx047. PMID 28472434.

- Law, C. J.; Slater, G. J.; Mehta, R. S. (2019). "Shared extremes by ectotherms and endotherms: Body elongation in mustelids is associated with small size and reduced limbs". Evolution. 0 (4): 735–749. doi:10.1111/evo.13702.

- King, Carolyn (1984). Macdonald, D. (ed.). The Encyclopedia of Mammals. New York: Facts on File. pp. 108–109. ISBN 978-0-87196-871-5.

- Kenyon, Karl W. (1969). The Sea Otter in the Eastern Pacific Ocean. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Wildlife.

- Amstislavsky, Sergei, and Yulia Ternovskaya. "Reproduction in mustelids." Animal Reproduction Science 60 (2000): 571-581.

- Dragoo and Honeycutt; Honeycutt, Rodney L (1997). "Systematics of Mustelid-like Carnivores". Journal of Mammalogy. 78 (2): 426–443. doi:10.2307/1382896. JSTOR 1382896.

- Wund, M. (2005). "Mustelidae". Animal Diversity Web. University of Michigan. Retrieved 2020-08-14.

- Perrin, William F., Wursig, Bernd, and Thewissen, J.G.M. Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals, 2nd ed. Academic Press; 2 edition (December 8, 2008). Page 529.

- Lodé, Thierry; Cornier, J. P.; Le Jacques, D. (2001). "Decline in endangered species as an indication of anthropic pressures: the case of European mink Mustela lutreola western population". Environmental Management. 28 (6): 727–735. Bibcode:2001EnMan..28..727L. doi:10.1007/s002670010257. PMID 11915962.

- Nascimento, F. O. do (2014). "On the correct name for some subfamilies of Mustelidae (Mammalia, Carnivora)". Papéis Avulsos de Zoologia (São Paulo). 54 (21): 307–313. doi:10.1590/0031-1049.2014.54.21.

- Valenciano, A.; Jiangzuo, Q.; et al. (March 2019). "First Record of Hoplictis (Carnivora, Mustelidae) in East Asia from the Miocene of the Ulungur River Area, Xinjiang, Northwest China". Acta Geologica Sinica. 93 (2): 251–264. doi:10.1111/1755-6724.13820.

- Morlo, M.; LeMaitre, A.; et al. (November 2019). "First record of the mustelid Trochictis (Carnivora, Mammalia) from the early Late Miocene (MN 9/10) of Germany and a re-appraisal of the genus Trochictis". Historical Biology. doi:10.1080/08912963.2019.1683172.

- Koepfli, Klaus-Peter; Deere, K.A.; Slater, G.J.; Begg, C.; Begg, K.; Grassman, L.; Lucherini, M.; Veron, G.; Wayne, R.K. (February 2008). "Multigene phylogeny of the Mustelidae: Resolving relationships, tempo and biogeographic history of a mammalian adaptive radiation". BMC Biology. 6: 10. doi:10.1186/1741-7007-6-10. PMC 2276185. PMID 18275614.

Further reading

| Wikispecies has information related to Mustelidae |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mustelidae. |

- Whitaker, John O. (1980-10-12). The Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Mammals. Alfred A. Knopf. p. 745. ISBN 978-0-394-50762-0.

External links

- "The Mighty Weasel" February 19, 2020 Nature