National Museum of Anthropology (Mexico)

The National Museum of Anthropology (Spanish: Museo Nacional de Antropología, MNA) is a national museum of Mexico. It is the largest and most visited museum in Mexico. Located in the area between Paseo de la Reforma and Mahatma Gandhi Street within Chapultepec Park in Mexico City,[3] the museum contains significant archaeological and anthropological artifacts from Mexico's pre-Columbian heritage, such as the Stone of the Sun (or the Aztec calendar stone) and the Aztec Xochipilli statue.

Museum's front entrance, depicting: MUSEO NACIONAL DE ANTROPOLOGÍA | |

%26groups%3D_377d11f051a77a3148e792c9ee0c500f80d51bee.svg)

| |

| Established | 1964 |

|---|---|

| Location | Mexico City, Mexico |

| Coordinates | 19.426°N 99.186°W |

| Type | Archaeology museum |

| Collection size | 600,000 [1] |

| Visitors | 2,336,115 (2017)[2] |

| Public transit access | Auditorio Station (line 7) |

| Website | www |

The museum (along with many other Mexican national and regional museums) is managed by the Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia (National Institute of Anthropology and History), or INAH. It was one of several museums opened by Mexican President Adolfo López Mateos in 1964.[4].

Assessments of the museum vary, with one considering it "a national treasure and a symbol of identity. The museum is the synthesis of an ideological, scientific, and political feat."[5] Octavio Paz criticized the museum's making the Mexica (Aztec) hall central, saying the "exaltation and glorification of Mexico-Tenochtitlan transforms the Museum of Anthropology into a temple."[6]

Architecture

Designed in 1964 by Pedro Ramírez Vázquez, Jorge Campuzano, and Rafael Mijares Alcérreca, the monumental building contains exhibition halls surrounding a courtyard with a huge pond and a vast square concrete umbrella supported by a single slender pillar (known as "el paraguas", Spanish for "the umbrella"). The halls are ringed by gardens, many of which contain outdoor exhibits. The museum has 23 rooms for exhibits and covers an area of 79,700 square meters (almost 8 hectares) or 857,890 square feet (almost 20 acres).

History

At the end of the 18th century, by order of the viceroy of Bucareli, the items that formed part of the collection by Lorenzo Boturini — including the sculptures of Coatlicue and the Sun Stone — were placed in the Royal and Pontifical University of Mexico, forming the core of the collection that would become the National Museum of Anthropology.

On August 25, 1790, the Cabinet of Curiosities of Mexico (Gabinete de Historia Natural de México)[note 1] was established by botanist José Longinos Martínez. During the 19th century, the museum was visited by internationally renowned scholars such as Alexander von Humboldt. In 1825, the first Mexican president, Guadalupe Victoria, advised by the historian Lucas Alamán, established the National Mexican Museum as an autonomous institution. In 1865, the Emperor Maximilian moved the museum to Calle de Moneda 13, to the former location of the Casa de Moneda.

In 1906, due to the growth of the museum's collections, Justo Sierra divided the stock of the National Museum. The natural history collections were moved to the Chopo building, which was constructed specifically to shelter permanent expositions. The museum was renamed the National Museum of Archaeology, History and Ethnography, and was re-opened September 9, 1910, in the presence of President Porfirio Díaz. By 1924 the stock of the museum had increased to 52,000 objects and had received more than 250,000 visitors.

In December 1940, the museum was divided again, with its historical collections being moved to the Chapultepec Castle, where they formed the Museo Nacional de Historia, focusing on the Viceroyalty of the New Spain and its progress towards modern Mexico. The remaining collection was renamed the National Museum of Anthropology, focusing on pre-Columbian Mexico and modern day Mexican ethnography.

The construction of the contemporary museum building began in February 1963 in the Chapultepec park. The project was coordinated by architect Pedro Ramírez Vázquez, with assistance by Rafael Mijares Alcérreca and Jorge Campuzano. The construction of the building lasted 19 months, and was inaugurated on September 17, 1964, President Adolfo López Mateos, who declared:

The Mexican people lift this monument in honor of the admirable cultures that flourished during the Pre-Columbian period in regions that are now territory of the Republic. In front of the testimonies of those cultures, the Mexico of today pays tribute to the indigenous people of Mexico, in whose example we recognize characteristics of our national originality.

The film Museo tells the story of the famous robbery to the National Museum of Anthropology on December 25, 1985, in Mexico City.

Exhibits

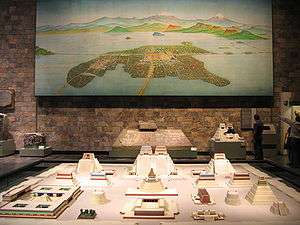

The museum's collections include the Stone of the Sun, giant stone heads of the Olmec civilization that were found in the jungles of Tabasco and Veracruz, treasures recovered from the Maya civilization, at the Sacred Cenote at Chichen Itza, a replica of the sarcophagal lid from Pacal's tomb at Palenque and ethnological displays of contemporary rural Mexican life. It also has a model of the location and layout of the former Aztec capital Tenochtitlan, the site of which is now occupied by the central area of modern-day Mexico City.

The permanent exhibitions on the ground floor cover all pre-Columbian civilizations located on the current territory of Mexico as well as in former Mexican territory in what is today the southwestern United States. They are classified as North, West, Maya, Gulf of Mexico, Oaxaca, Mexico, Toltec, and Teotihuacan. The permanent expositions at the first floor show the culture of Native American population of Mexico since the Spanish colonization.

The museum also hosts visiting exhibits, generally focusing on other of the world's great cultures. Past exhibits have focused on ancient Iran, Greece, China, Egypt, Russia, and Spain.

Exhibits gallery

.jpg) Reproduction of the Temple of the feathered serpent in Teotihuacan

Reproduction of the Temple of the feathered serpent in Teotihuacan- Disc of Mictlantecuhtli

- Statue of Chalchiuhtlicue

Olmeca-Xicalanca - Cacaxtla bird man mural

Olmeca-Xicalanca - Cacaxtla bird man mural Mural and model of Tenochtitlan, looking east

Mural and model of Tenochtitlan, looking east Ocelotl-Cuauhxicalli

Ocelotl-Cuauhxicalli Teocalli of the sacred war

Teocalli of the sacred war- Statue of Xiuhcoatl

Statue of Aztec goddess Coatlicue

Statue of Aztec goddess Coatlicue.jpg)

- Skull covered with turquoise

Replic of Codex Borbonicus

Replic of Codex Borbonicus- Feather headdress replic of Moctezuma II

- Relief of Toniná

Lintel 26, Yaxchilan

Lintel 26, Yaxchilan Ceramic of the Jaina Island

Ceramic of the Jaina Island- Reproduction of the mausoleum of the Palenque ruler, K'inich Janaab' Pakal

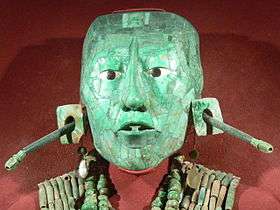

Mortuary mask of K'inich Janaab' Pakal

Mortuary mask of K'inich Janaab' Pakal.jpg) Frieze of Placeres

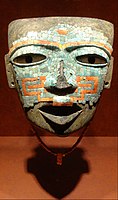

Frieze of Placeres Mask of Chaac

Mask of Chaac Zapotec mask of the Bat God

Zapotec mask of the Bat God Reproduction of the Tomb 105 of Monte Albán

Reproduction of the Tomb 105 of Monte Albán Mixtec ceramic

Mixtec ceramic Mixtec pectoral of gold and turquoise, Shield of Yanhuitlán

Mixtec pectoral of gold and turquoise, Shield of Yanhuitlán.jpg)

_MQ.jpg)

- Reproduction of the sculpture of Mictlantecuhtli in El Zapotal

Mask of Malinaltepec

Mask of Malinaltepec Figure of a pelota player.

Figure of a pelota player. Ball Game Goal, Chichen Itza.

Ball Game Goal, Chichen Itza.

See also

- Doris Heyden

- Felipe R. Solís Olguín, director 2000–2009

Further reading

- Aveleyra, Luis. "Plantación y metas del nuevo Museo Nacional de Antropología. Artes de México, época 1, año 12, no. 66-67: 12-18. Mexico 1965.

- Bernal, Ignacio. El Museo Nacional de Antropología de México. Mexico: Aguilar 1967.

- Castillo Lédon, Luis. El Museo Nacional de Arquelogía, Historia, y Etnografía. Mexico: Imprenta del Museo Nacional de Arquelogía, Historia, y Etnografía 1924.

- Fernández, Miguel Ángel. Historia de los Museos de México. Mexico: Fomento Cultural del Banco Nacional de México 1987.

- Florescano, Enrique. "The Creation of the Museo Nacional de Antropología of Mexico and its scientific, educational, and political purposes." In Nationalism: Critical Concepts in Political Science, edited by John Hutchinson and Anthony D. Smith. Vol. IV. pp. 1238-1259. London and New York: Routledge, 2000. Reprinted from Collecting the Pre-Columbian Past: A Symposium at Dumbarton Oaks 6th and 7th October 1990, Elizabeth Hill Boone (ed.), Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 1993, pp. 83-103.

- Galindo y Villa, Jesús. "Apertura de las clases de historia y arqueología." Boletín del Museo Nacional I: 22-28, Mexico 1911.

- Galindo y Villa, Jesús. "Museología. Los museos y su doble función educativa e instructiva." In Memorias de la Sociedad Científica Antonio Alzate 39:415-473. Mexico 1921.

- León y Gama, Antonio de Descripción histórica y cronológica de las Dos Piedras. Mexico: Instituto Nacional de Antropología 1990.

- Matos, Eduardo. Arqueología e indigenismo. Mexico: Instituto Nacional Indigenista, 1986.

- Matute, Alvaro. Lorenzo Boturini y el pensamiento histórico de Vico. Mexico: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México 1976.

- Mendoza, Gumersindo and J. Sánchez, "Catálogo de las colecciones históricas y arqueológica del Museo Nacional de México." Anales del Museo Nacional pp. 445-486. Mexico 1882.

- Núñez y Domínguez, José, "Las clases del Museo Nacional." Boletín del Museo Nacional, segunda época: 215-218. Mexico 1932.

- Paz, Octavio. Posdata. Mexico: Siglo Veintiuno Editories 1969.

- Ramírez Vázquez, Pedro. "La arquitectura del Museo Nacional de Antropología". Artes de México, época 2, 12 (66-67): 19-32. Mexico: 1965.

- Villoro, Luis. Los grandes momentos del indigenismo. Mexico: Casa Chata 1979.

Notes

- This early cabinet of curiosities, Gabinete de Historia Natural de México, became years later the nowadays Museo de Historia Natural in Mexico City.

References

- Britannica. "National Museum of Anthropology".

- "Estadística de Visitantes" (in Spanish). INAH. Archived from the original on 8 July 2012. Retrieved 25 February 2018.

- "Plan Your Visit Archived 2017-02-10 at the Wayback Machine." National Museum of Anthropology. Retrieved on April 12, 2016. "The Museum is located at Av. Paseo de la Reforma y Calzada Gandhi s/n, Col. Chapultepec Polanco. Delegación Miguel Hidalgo. C.P. 11560, México, D.F."

- Arnaiz y Freg, Arturo. "Los Nuevos museos y las restauraciones realizados por el Presidente López Mateos." Artes De México, no. 179/180, 1974, pp. 62–67. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/24317704 accessed 11 March 2019

- Enrique Florescano, "The creation of the Museo Nacional de Antropología and its scientific, educational, and political purposes." In Nationalism: Critical Concepts in Political Science, Vol. IV p. 1257. John Hutchinson and Anthony D. Smith, eds. London and New York: Routledge 2000.

- Octavio Paz, Posdata, Mexico: Siglo Veintiuno 1969, quoted in Florescano, "The creation of the Museo Nacional de Antropología", p. 1258, footnote 9.

- Museo Nacional de México (1877-01-01). Anales del Museo Nacional de México. México : El Museo.

- Ana Mónica Rodríguez (April 27, 2011). "Espectadores podrán conocer el enigma del huipil de La Malinche". La Jornada. Mexico City. p. 4. Retrieved May 5, 2012.